Reigniting Perception

Runa Islam and Artists’ Film

The impending obsolescence of motion picture celluloid film made the medium affordable to Runa Islam when she first came to work with it in the 1990s. With the rise of analog video in the consumer market, second-hand Super-8 and 16mm equipment was relatively cheap and abundant. Experimenting with different media, she embraced the transitional moment in the life of film, observing that “this mode of operation was based on contingent ground.”1 The initial window of opportunity began to close in the past decade with the advancing of digitalization in the motion picture industry. The widespread and rapid disappearance of specialist labs and film stocks forced Islam to contend with questions about the future viability of artists’ film. Works bound conceptually to analog material and increasingly expensive playback equipment faced potential demise. The direct impact of film lab closures in London on Islam’s practice came up in our early conversations when developing the solo exhibition Runa Islam: Verso (2016–17) at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), as the background to certain works and shift in working practice during this period.

Born in Dhaka, Bangladesh and raised in London (where she is based), Islam belongs to a generation of international contemporary artists who first became known for making film specifically for the exhibition gallery context as well as ushering a cinematic turn within video art in the 1990s. This high profile of the projected image and performance partly informed the resurgence of scholarship and preservation initiatives on the history of experimental film and video in Britain. For example, a range of venues have since demonstrated a commitment to restaging iconic expanded cinema works from the 1970s by such figures as Lis Rhodes, Anthony McCall, Malcolm LeGrice, among others. The late Tony Sinden observed that “expanded cinema opened a door that has enabled us to encounter both sides of the screen: experience both the subject and making of the work in an unexpected way: extending a dialogue between the moving image, spectator and exhibition context.”2

Islam builds on strategies of structural film in her attention to both sides of the screen, the emphasis placed on the filmic apparatus, and the participatory role of visitor movement. The viewing space and projection device are integral parts of the installations. Therefore, analog film is not merely an image carrier that could easily lend itself to the option of a digital transfer.

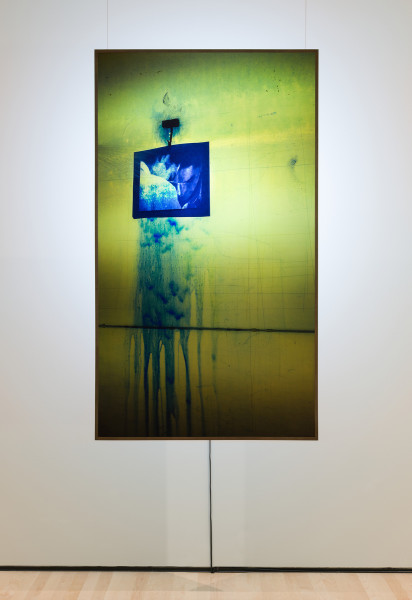

Runa Islam, Cabinet of Prototypes, 2009-10

16mm color film, silent, 7 min., with projector and screen in vitrine, and light filter

© Runa Islam

Photo: Ben Westoby, courtesy White Cube

Runa Islam: Verso brings together for the first time two 16mm film installations, Cabinet of Prototypes (2009–10) and Magical Consciousness (2010). These works stemmed from Islam’s 2008 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship exploring the institution’s collections and archives, in particular, her time with the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. Made in “the same breath,” they reflect an interest in behind-the-scenes aspects of collections and display and traverse the threshold between film and sculpture. The shared focus on shifts between invisibility and visibility informed the material transformations in the more recent projects on view, which consider the physical elements behind the illusion of film.

In her subject matter, the artist has often gravitated to the overlooked or peripheral. Cabinet of Prototypes foregrounds the sculptural qualities of armatures custom-designed for the presentation of artifacts—subordinate forms to absent, valued objects. Through close-ups and panning shots these elements begin to resemble abstract compositions, anti-monumental “prototypes” for the type of large-scale outdoor sculpture associated with the original viewing location of a sculpture park. The film was commissioned for the Kivik Art Centre in Österlen, Sweden, and paired with architect Petra Gipp’s concrete and wood pavilion Refugium set in the forest grounds. For Islam’s 2012 solo exhibition at the former location of White Cube in London, she then reconfigured this film for the gallery context as a cinematic sculpture, enclosing both projector and screen in a glass vitrine table.

Islam considers this work to be a culmination of a period of investigating the shift of film into sculpture: “By (re)framing Cabinet of Prototypes within the glass vitrine, the objectness of its materials—the projector, the screen and the content of the film—are all held in an equivalence, by which I hope medium specificity is expanded rather than collapsed.”3 It was partly inspired by a glass pavilion on the Kivik Art Centre property designed by Snøhetta – the architectural firm for SFMOMA’s new building expansion. Through a desire to somehow retain a loose associative link to the original natural environment, Islam added a yellow filter to the gallery’s window that intensified the green color of the trees in Hoxton Square. The length of the custom table vitrine bears an indexical relationship to a tall projector stand that had supported a longtime presence in her studio – an orchid plant with protruding aerial roots.4 When Cabinet of Prototypes is shown without a view of nature, she has explored adding the presence of plants.

Runa Islam, Cabinet of Prototypes, 2009-10

16mm color film, silent, 7 min., with projector and screen in vitrine, light filter, and plant, dimensions variable

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase, by exchange, through a fractional gift of Shirley Ross Davis and the Accessions Committee Fund

© Runa Islam

Photo: Katherine Du Tiel, courtesy SFMOMA

At SFMOMA, we considered a few existing and false window options and chose to create window from the back wall of the media gallery looking through a potted palm into the SFMOMA Conservation Workroom to establish a conceptual and physical link between display and preservation. The gallery became triangulated with the institutional and artist workspaces as reflected in the content of the works. SFMOMA had built a walled-in door at that one spot to allow for a future albeit unlikely possibility of opening onto this sunlit area (also visible to visitors from the adjacent tall terrace windows). For the artist, this blur between public and private spaces points to an increasing porousness in museum design and programming.

Since 2007 the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship program has fostered open-ended research. Navigating the sheer magnitude of the museum’s collections and archive seemed an impossible prospect. Islam’s discovery process therefore moved towards finding examples of things not already mapped or canonized, such as that storage of hooks and armatures or flawed glass plates.5 In looking at a series of Japanese screens, Islam recounts, “I remember seeing the back of the screen on display and catching this light, the gold exuded a presence behind the vitrine …The curator couldn’t [later] find it for me because it isn’t defined in the categorization of this work.”6

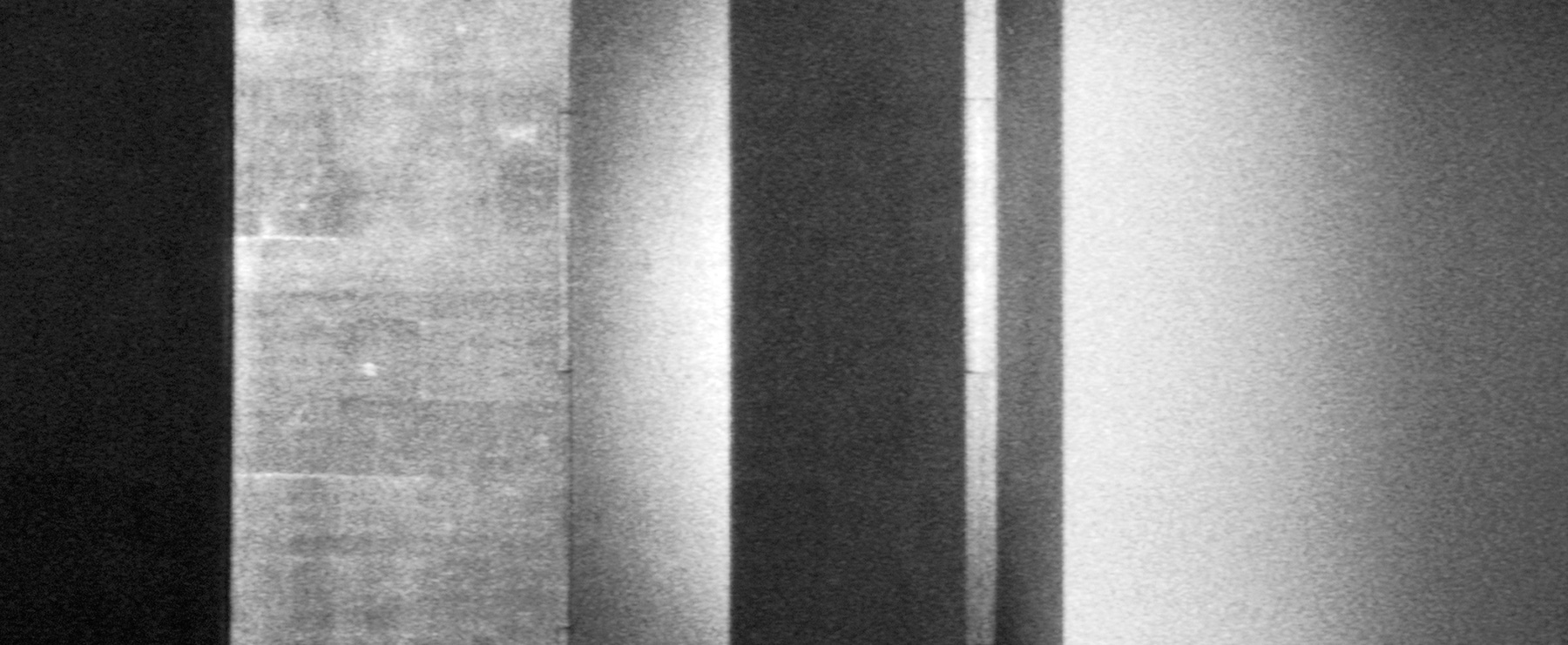

Runa Islam, still from Magical Consciousness, 2010

Anamorphic 16mm film, black and white, silent, 8:22 min.

© Runa Islam

Photo courtesy White Cube

Shot in black and white, Magical Consciousness turns a rare example of a gilded back of a six-panel, sixteenth-century Japanese folding screen into a meditation on the “silver screen” of cinema. The sequences move through variations of illumination and shadow, surface and support. Six times the screen is fully opened and the projected image fits the suspended screen, spatially conflating the similar wide formats of these classical and modern screens and evoking the idea of the internal screen of consciousness.7 The title refers to Vilém Flusser’s notion of a mode of pre-historical looking discussed in Towards a Philosophy of Photography (1983). Through a nonlinear scanning of the surface and changing light formations, the gaze becomes mobilized and “perception reignited,” as Islam notes, in watching this counter-narrative within the fold/unfolding screen. Islam has continually engaged with the histories of cinema, dismantling and reconstructing film models. Her experimental approach to the materiality and architecture of film opens up the potential for new perspectives to emerge.

In This Much is Uncertain (2009–10) – another film made at that time that also borders on abstraction (which was not included in the SFMOMA exhibition) – the silver grain of film is recalled through shots of the volcanic glittery sand of the island location of Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli, Land of God (1950). Islam furthered the allusion to alchemical transformation in Magical Consciousness through sculptures and drawings considering the raw material of film silver.

Runa Islam, Anatomical Study (Instruments), 2013

Silver recouped from film processing, 1 15/16 x 2 3/4 in.

Courtesy the artist and White Cube

© Runa Islam

Photo: George Darrell, courtesy White Cube

Fujifilm had ceased production of the majority of its motion picture film products in 2013. While visiting a Fuji lab within a few weeks of its closing, Islam inquired what would happen to the remaining inventory of film stock. She learned of the plan to retrieve the silver through a process that involves incineration. For the artist, this residual element offered a vehicle to carry on working with celluloid film in a different way. She made a cast of the 16mm film lens she had used for the majority of her films over the past fifteen years, which was for the artist a metaphoric eye laden with images representing “a corpus of film, a body of time, a body of images.” In Runa Islam: Anatomical Study (2014) at KIOSK, a former anatomical theater in Ghent, Belgium, she first premiered this series that features items from the artist’s studio cast in “latent” silver reclaimed from exposed celluloid.

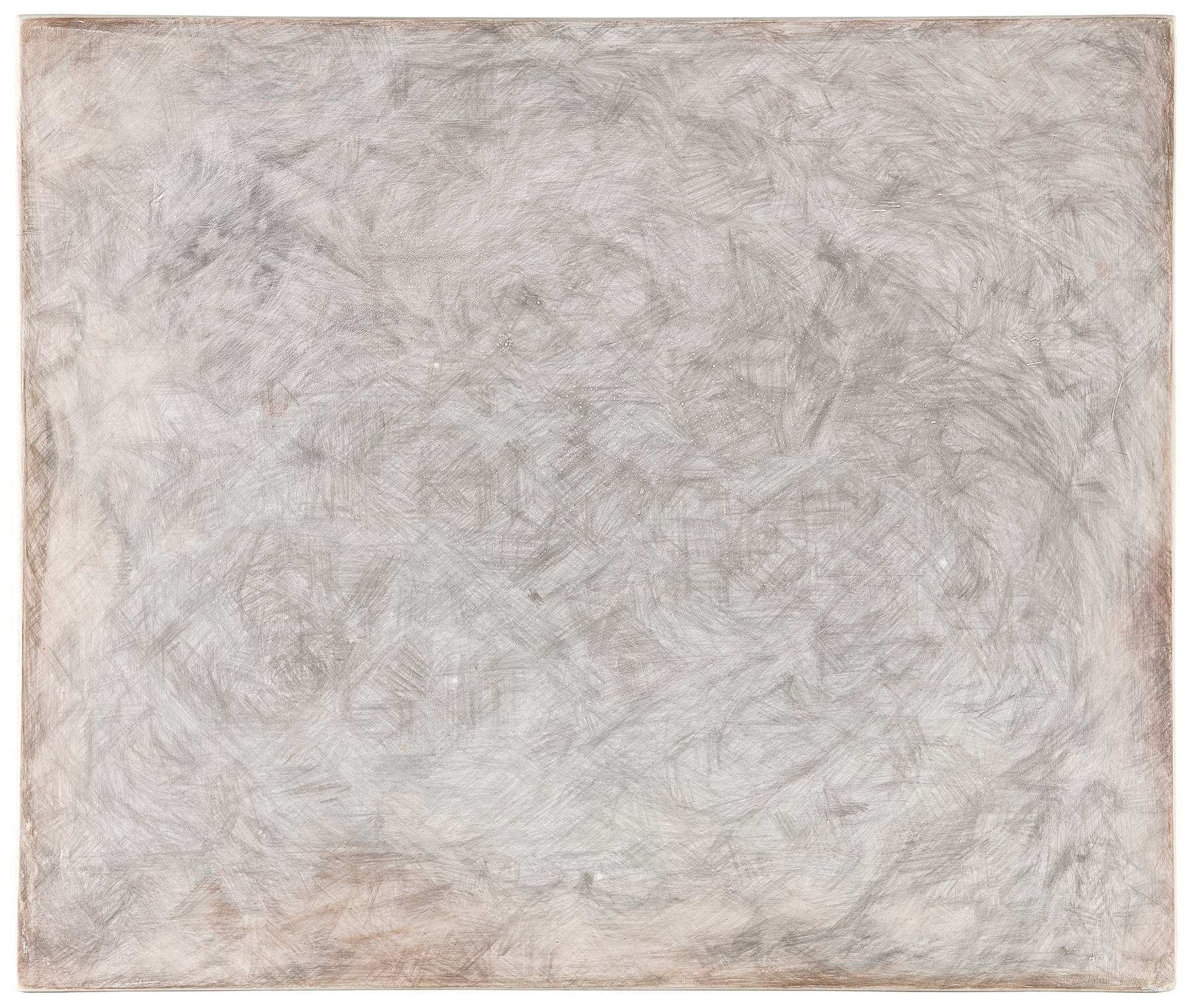

The desire to return to a fundamental way of working, to register an image through mark-making, led to silverpoint drawings including the ongoing series . . . laws of night and honey . . . . . . (2016), created with the resulting cast-silver objects, including pencils she has kept for many years. The small gesso panels, often used for icon paintings, become highly reflective through the accumulation of marks covering the delicate surface. These labor-intensive drawings not only recall the hand-application of opulent gold leaf on the otherwise purely functional side of the Japanese screen, but pick up the notion of writing with the camera that Islam had explored in two films from 2008 that utilized a robotic motion camera to spell out text.

Runa Islam, …laws of night and honey…… #3, 2016

Silver recouped from film processing on gesso panel, 11 13/16 x 9 13/16 x 3/8 in.

Courtesy the artist and White Cube

© Runa Islam

Photo: Katherine Du Tiel, courtesy SFMOMA

Based on two surviving stills from Islam’s lost 16mm film The First Glance (2000), the works comprising After The First Glance (2016) gesture to the re-embodiment of the subject of that lost film in different media. Cinema becomes pared down to its bare elements of a light source and a screen. In the case of After the First Glance (Peacock) (2016), a backlit, suspended color transparency depicts the moment of rinsing off the blue ink from a silkscreen transfer foil to reveal the photographic subject. This past spring, Islam discovered that this early film she planned to lend to the group exhibition Prediction at Mendes Woods in São Paulo was missing. The First Glance (2000) was “amongst all the untraceable negative rushes of my films made during the period 1999 to 2007. (Rushes refer to anything that didn’t make a final film negative copy.) Hours of footage related to many other films. But also entire negatives of lesser frequently printed films too,” notes the artist.8 The entire reel was held at the lab and a negative cut was never produced given the artist’s budget restrictions. Once the lab closed, it came to light that the outsourced negative cutting department had closed over a year before and allegedly no rushes were transferred or traceable.

Soho Film Lab in London, the last professional lab in the United Kingdom to print 16mm, stopped offering that service under new ownership in 2011. In the wake of this loss, the artist Tacita Dean described, “These last few days have been like having my bag stolen and remembering, bit by bit, what I had inside it. My relationship with the lab is an intimate one; they watch over my work, and are, in a sense, its protectors. I have made more than 40 films, and each one has several inter-negatives (a copy of the original negative). In the vaults of Soho Film Lab are racks packed high with cans containing my life’s work to date, including the negatives of films I never made.”9 The necessity of shifting the production of filmic work to Europe posed a financial and logistical challenge of access for many artists and venues based elsewhere. Islam was one of artist filmmakers invited to contribute to Dean’s accompanying publication FILM on the occasion of The Unilever Series: Tacita Dean (2011–12) at the Tate Modern. During her remarks at the Media in Transition conference at the Tate in 2015, Islam revisited this text and that moment of crisis for an international community of artists and independent filmmakers and their advocacy for a viable coexistence of celluloid and digital technologies.

At the time Cabinet of Prototypes entered the SFMOMA collection we did not know when there would be an opportunity to exhibit this film installation or how feasible it would be to identify a lab to produce the required exhibition copy prints for display at a future date. Kodak’s renewed commitment to manufacture 16mm film and the continuation of celluloid services at select professional labs in California and Europe have encouraged the museum’s ability to both collect and exhibit 16mm film in a show such as this one or the touring retrospective Bruce Conner: It’s All True (2016).10 Working closely with artists and artists’ estates to more fully understand the intentions and life trajectories of works has been essential to developing an approach to exhibiting film installations.

1Keynote speech by Runa Islam, “Media in Transition” conference at Tate Modern, November 18-20, 2015. Recordings: http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/media-transition

2See artist’s website: www.tonysinden.com.

3Email with the author, 2014.

4The aerial roots and leaves of this plant were cast in recouped silver from film processing as twelve pieces in Anatomical Study (dead orchid) (2014).

5Islam’s research at the Freer and Sackler Galleries additionally led to the 35mm film projection Emergence (2011), based on a cracked glass plate by by Antoin Sevruguin, an official photographer from the Imperial Court of Iran.

6Islam in conversation.“Stedelijk at de Ateliers with Runa Islam and Willem de Rooij” from Stedelijk Museum, 4.11.2012. https://vimeo.com/40537381

7Email with the author, 2016.

8The Japanese screen coincidentally is discussed in film director’s Sergei Eisenstein account of his first conscious childhood impression in “History of the Close-Up.”

9Tacita Dean, “Save celluloid, for art’s sake,” The Guardian, February 22, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/feb/22/tacita-dean-16mm-film

10SFMOMA worked with FotoKem in Burbank, California, and Islam’s preferred labs in Europe, Haghefilm Digitaal, Amsterdam, and DeJonghe Film Postproduction, Kortrijk, Belgium.

main image:

Runa Islam, Anatomical Study (Instruments), 2013

Silver recouped from film processing; 1 15/16 x 2 3/4 in.

Courtesy the artist and White Cube

© Runa Islam

Photo: George Darrell, courtesy White Cube