BALANCING PRESERVATION STRATEGY & ARTIST INTENT

Treatment of a Unique Chromogenic Print by Matthew Brandt

In 2012, Matthew Brandt created the photograph Mary’s Lake MT 9 (2012). It was acquired by the Department of Photographs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in the same year. Although the large-format photograph is a chromogenic print – the most common color photographic process of the 20th century – creative post-processing steps involving selective destruction of the image layer transformed it from a classic example of a familiar photographic process to a unique print with unusual conservation challenges. With active flaking and losses in several areas of the print, stabilizing treatment seemed imminent. But would conservation intervention conform to the artist’s intent? To answer this and other questions, Brandt was consulted on treatment and long-term preservation strategies.

In his work, Matthew Brandt focuses heavily on the materiality of photography and creates strong connections between the component materials of each print with its subject matter. He began his studies at Cooper Union with a focus on drawing and painting and only later experimented with photography, often in unexpected contexts such as sculpture courses. His unconventional approach to photography evolved further during his graduate studies at The University of California, Los Angeles when he worked with James Welling, who encouraged experimentation combined with a strong foundation in traditional printing processes.1

Brandt’s body of work represents an impressive spectrum of historic and contemporary processes that range from the origins of photography to the present day. His printing methods include heliography, salted paper, carbon, gum dichromate, photogravure, silkscreen, diazotype, silver gelatin, chromogenic, dye diffusion (Polaroid), and inkjet. Although some of his prints are conventional examples of their process, most are imaginative deviations from the original. His variations in technique relate intimately to the subject matter. For example, in a recent series he used the 19th-century gum-dichromate process to print images of demolished buildings substituting dust gathered from the site for traditional pigments. He has made salted paper prints using salt extracted from his subjects; in one series he used salt water drawn from depicted bodies of water, and in another, the bodily fluids of his portrait sitters.

Fig. 1. Matthew Brandt, Mary’s Lake, MT 9, 2012

Chromogenic print on Kodak Supra Endura smooth matte paper, 182.9 x 266.7 cm (72 x 105 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2012.411

Photo credit: Bruce Schwartz. Courtesy Matthew Brandt

Mary’s Lake MT 9 is part of Brandt’s Lakes and Reservoirs series, comprising chromogenic prints of bodies of water in the American West. The prints were thoroughly processed using all of the standard steps for chromogenic photographs and then were post-processed by immersion for varying amounts of time in water extracted from the body of water represented in the image. Soaking the print in water caused the partial destruction of the image layers, resulting in colorful abstractions of the original image.

Brandt embraces the unexpected and accidental in his work, while at the same time he clearly has a deep understanding of photographic techniques and chemistry. This helps to explain the success of so many of his experimental prints. Understanding certain aspects of the technical history of analog photography illuminates his methods. Since its beginnings in the mid-19th century, the medium has relied on the light sensitivity of silver halides. In processes such as salted paper or gelatin silver, the final image material is metallic silver converted from the silver salts used to sensitize the paper. Understanding this underlying chemistry, Brandt reasoned that he could use salts from ocean water or bodily fluids combined with silver nitrate as an unconventional source for the light-sensitive silver salts in his salted paper prints. Among the unknowns in these scenarios are the exact types and quantities of salts and their interaction with any additional substances in his source material.

The final image of most color photographic processes comprises dyes rather than metallic silver. However, silver halides still perform a critical role in the initial stages of image formation, linking this process to the earliest forms of photography. The silver is completely removed in the final stages of processing, leaving three discrete layers of dye in gelatin with yellow on the bottom, magenta in the middle, and cyan on top. These dye layers in conjunction form a full-color image.2

Although chromogenic papers are still commercially available and widely used, inkjet printing processes are increasingly pervasive. At this advanced stage in the evolution and adoption of digital photography and printing, even Brandt’s decision to make chromogenic prints could be viewed as homage to analog photography practices. Through his selective destruction, he takes this further by revealing the structure of the print itself, making the component materials of the photograph a dominant aspect of the piece.

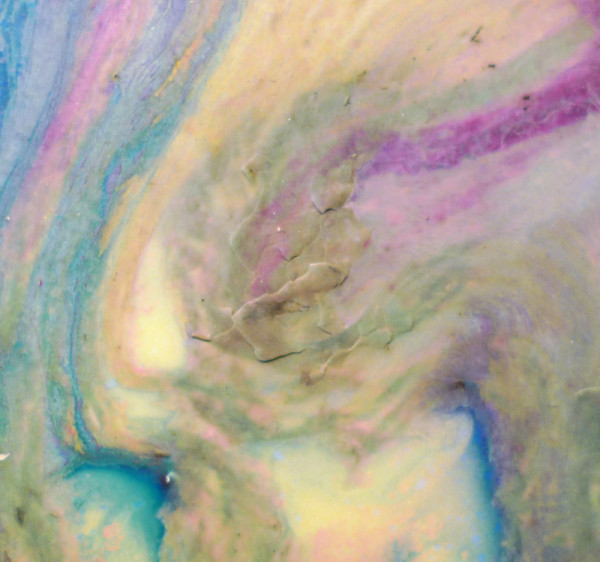

Like others in the Lakes and Reservoirs series, Brandt’s post-processing step for Mary’s Lake MT 9 involved prolonged soaking of the print in water extracted from Mary’s Lake, a freshwater lake in Montana. The soaking caused the gelatin layers to swell, making the gelatin and embedded dyes move and redeposit in swirls of color. In places with longer soaking times, vibrant yellow from the bottom dye layer and red, created by the magenta layer over the yellow, encroach on a partially intact full-color image at the center (fig. 2). The top cyan layer reads like a translucent scrim that has twisted and folded over itself, revealing an alien landscape composed of only the remaining magenta and yellow (fig. 3).

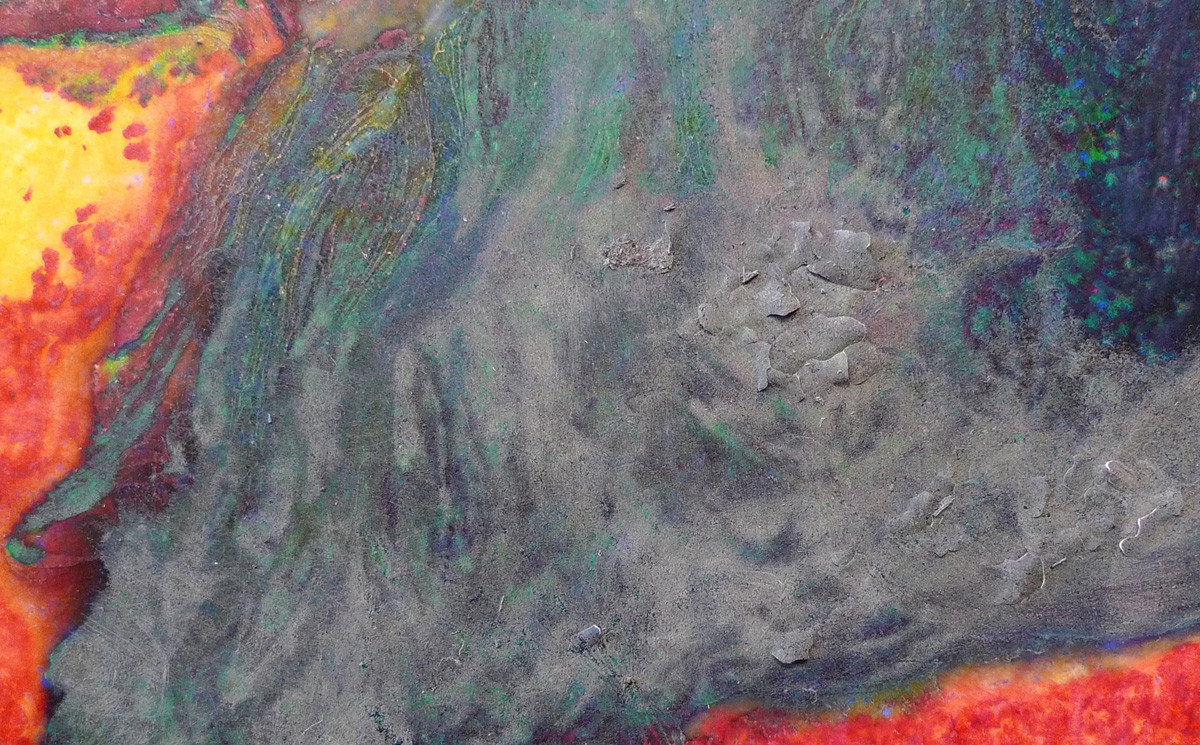

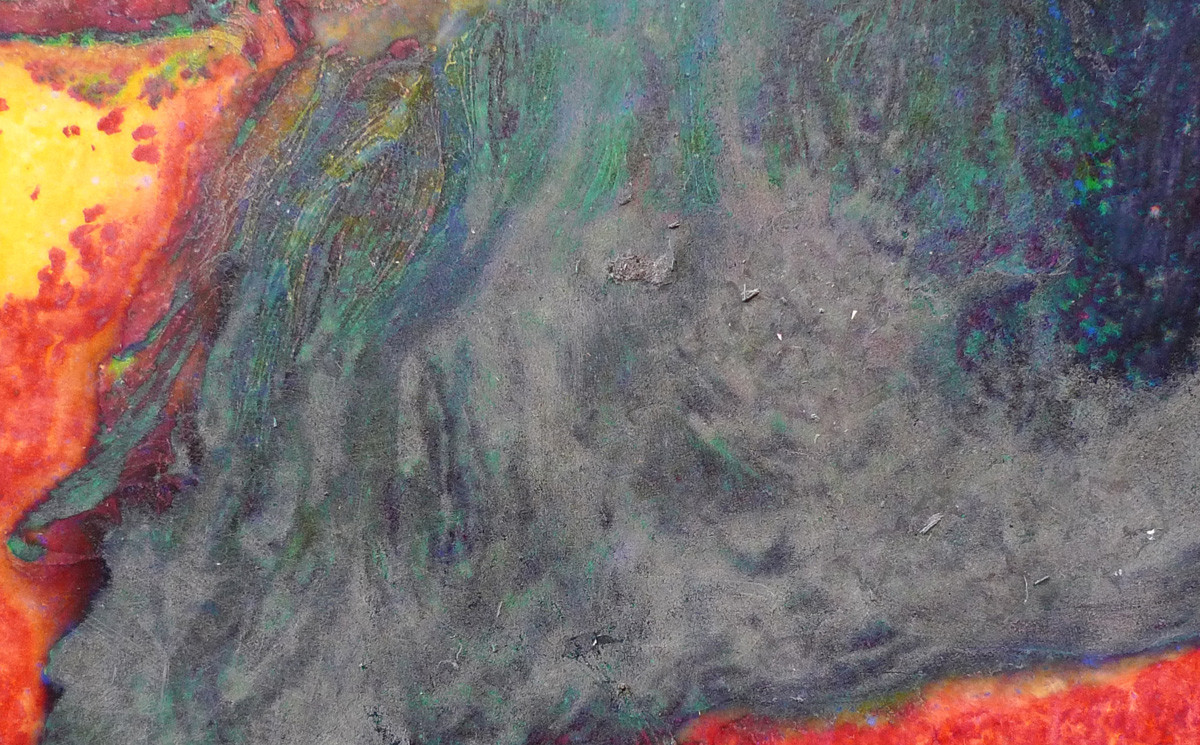

Unlike the smooth, machine-made surface it would have had without soaking, this print has an almost sculptural topography with overall distortion of the resin-coated support and a varied surface texture with areas where the gelatin binder has redeposited in thick, glossy masses. Other sections have a thinner binder layer with a matte, powdery-looking surface (figs. 4, 5). Grass and other small pieces of biological material are adhered to the surface, the result of exposure to the natural, unfiltered water source.

Flaking (figs. 6, 7) and losses (figs. 8, 9) occurred exclusively in the matte, powdery areas, where the gelatin is particularly thin. Many of the flakes were large and curled away from the surface, and there were several losses that had already occurred with a few loose flakes found along the bottom of the frame interior when the piece arrived at the Museum.

This artwork’s physical state is a tangible expression of the ephemeral act of destruction. From a preservation perspective, a natural question arises: which aspect of this piece is most important, the physical materials or their destruction? The most conventional conservation approach without input from the artist would involve intervention through stabilization and aesthetic treatment in an effort to maintain the print’s appearance as close as possible to the moment of creation. However, if the act of destruction is deemed a critical facet of the work, the current physical deterioration must be accepted. The primary preservation question then becomes: at what point in the process of deterioration – if any – is conservation intervention appropriate? Even with proper care and handling in the future, without any intervention this piece will continue to flake and incur image losses until it reaches an “end point” when it is considerably altered.

It is the prerogative of the artist to determine the end point of a work of art. However, this threshold may be undefined until the artist is compelled to consider it. Once an artwork is accessioned by a museum, the curator and conservator become the decision makers with regard to preservation policy. Ideally, decisions are made with input from the artist, and equipped with this information, the conservator works to preserve the piece with the artist’s philosophy in mind. The resulting preservation strategy typically will fall somewhere on a spectrum between an extreme level of deterioration and proactive intervention.

During conversations and written correspondence with Brandt, it became clear that the degree of flaking on The Met’s piece was unusual compared with other works in the Lakes and Reservoirs series. The artist recalled that he had seen some minor flaking on other works and he had always considered it “part of the process” and “an inevitability.” After viewing images of the flaking on Mary’s Lake MT 9, Brandt remarked that he felt somewhat conflicted between the “very beautiful circumstances” of the flakes themselves and the desire to prevent the inevitable losses that would occur without treatment.3 The decision to intervene was not an entirely natural one. The ideal approach would have been to let the flaking continue, but only if it deteriorated at a considerably slower rate. Understanding that this was not possible, Brandt agreed that the flaking should be consolidated, but any existing losses would be left as they were with no aesthetic integration.

This resolution provides an equilibrium between the natural course of deterioration and preservation. In practice, its future care will require that its physical condition is maintained – likely through additional treatment campaigns – with the goal of preserving the photograph as it existed in 2013 when the treatment was carried out. While this decision was not arbitrary, it was not part of the artist’s “original intent.” The artwork behaved in an unexpected way, requiring the artist to reevaluate the work and adjust his ideas about longevity.

The distressed image layer of Mary’s Lake MT 9 is its greatest vulnerability but is also inherent to the core meaning of the piece. Future care will require a delicate balance between passive preservation and intervention to delay the continuous process of deterioration without attempting to reverse it. With the artist’s involvement and the documentation of his wishes for the future, the preservation plan is now entwined with the meaning of the piece. This will enable the Museum to respond appropriately to the future conservation needs of this singular work of art.

1 For further reading on this, see J. Bramowitz, “Matthew Brandt and a Handful of Dust” and Heckert, Harnly and Freeman, Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography.

2 For further information on chromogenic prints, see Lavédrine, Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation, 212–217 and Pénichon, Twentieth-century Color Photographs: Identification and Care, 186–187.

3 Matthew Brandt, written and verbal correspondence, 2012.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Matthew Brandt; Sarah Freeman, J. Paul Getty Museum; and colleagues at The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Nora Kennedy, Lisa Barro, Douglas Eklund, Rachel Mustalish, Yana van Dyke, Marina Ruiz-Molina, Isabel Duvernois, Meredith Reiss, Barbara Bridgers, Thomas Ling, Bruce Schwartz.

References

Bramowitz, J. “Matthew Brandt and a Handful of Dust.” Interview Magazine (2013). Accessed August 10, 2015. http://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/matthew-brandt#_.

Brandt, M. Written and verbal correspondence. 2012.

Graphics Atlas. Image Permanence Institute. http://www.graphicsatlas.org/.

Heckert, V., Harnly, M., Freeman, S. Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015.

Lavédrine, Bertrand. Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2009.

Li, S. J. “Matthew Brandt at M+B.” Art in America (March 2014). http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/reviews/matthew-brandt/.

Ollman, L. 2015. Review: ‘Light, Paper, Process’ an inventive subversion of photography. LA Times, May 1, 2015. http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-ca-light-paper-process-getty-photo-show-20150503-story.html.

Pénichon, S. Twentieth-century Color Photographs: Identification and Care. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2013.

Photo District News. “Lakes, trees and Honeybees.” PDN Photo of the Day, May 31, 2012. http://potd.pdnonline.com/2012/05/14813/.

Shaheen, S. “Waterworks: Matthew Brandt’s Experimental Landscapes.” The New Yorker, June 5, 2012. http://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/water-works-matthew-brandts-experimental-landscapes.