A Commitment to Perpetual Learning

Practical Training in Time-based Media Conservation

Practical training is integral to academic education in any conservation specialty. While graduate programs in the US have started to offer some course work related to time-based media conservation, they are typically missing critical lab infrastructure and specialized supervisors to provide practical training in this new area.

Thus, over the last few years, museum labs with dedicated time-based media (TBM) staff have been playing a major role in closing this gap and providing complementary training opportunities for emerging conservators. In the following conversation between Joanna Phillips and Alexandra Nichols, both sides of this scenario are illuminated: Phillips, as the Senior Conservator of Time-based Media at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, has been training interns and fellows in time-based media conservation since 2010. Nichols, who trained with Phillips from 2016 to 2017, has now moved on to The Metropolitan Museum of Art to work on their time-based media collection as a Sherman Fairchild Foundation Fellow.

Joanna Phillips: Alex, you were trained as an objects conservator at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation and were new to time-based media conservation when you started your Samuel H. Kress Fellowship with us a little more than a year ago. How hard was it for you to pick up this new specialty?

Alexandra Nichols: As a graduate student focusing on the conservation of contemporary art, I’d attended Electronic Media Group sessions at the American Institute for Conservation’s annual conferences for a few years, and I’d had some basic experience with time-based media artworks in my graduate internships at the Hirshhorn and the Museum of Modern Art. But it wasn’t until my fellowship at the Guggenheim that I was really immersed in time-based media conservation practices. I struggled at first with wrapping my head around some of the technical aspects, but I had a lot of help from you and video engineer Maurice Schechter in those first few months. During this period, I learned more about film and video history, and how that evolved into standardized resolutions and frame rates. During my graduate studies training in objects conservation, I had been taught how to identify and describe condition issues for a wide range of objects, but I hadn’t yet been trained to identify condition issues for analog and digital video, so seeing errors firsthand in artworks in the collection was extremely instructive. It helped that I was able to relate some of the concepts you find in video to my past experience with photography.

Phillips: A reservation that often prevents fine art conservators from engaging with the time-based media works in their collection is the technical nature of these works and their perceived “difference.” Did you ever share this viewpoint, and if so, did your exposure to TBM practice change your perspective?

Nichols: I have come across conservators that feel overwhelmed by the challenges of time-based media and their unfamiliarity with the medium. A lot of the focus in the art world is on original, physical objects, and it can be hard for conservators to think of digital files or replaceable equipment components as something with artwork status. Personally, I never shied away from or avoided learning about time-based media, I just didn’t have the opportunities during my studies to explore and address the issues in practice. I like to think of time-based media within the larger context of contemporary art rather than a completely separate field, as there are a lot of parallels with other forms of variable art, such as installation art or conceptual art that can be reconfigured or refabricated each time it is exhibited. Tim Hawkinson’s immense installation Überorgan (2000), for example, is reminiscent of a pipe organ, hot air balloon, and player piano all in one. Due to its size, it has been installed in very large spaces, such as Mass MoCA, which has an immense open space about the size of a football field, but it has also been installed in smaller galleries, such as Ace Gallery in New York, where the installation was split up between six different rooms. Each time this is displayed, the artwork is altered or adjusted in some way to work within its environment.

Just like conservators of contemporary objects, paintings, works on paper, etc., time-based media conservators collaborate closely with living artists. To truly collect and own works with variable and conceptual aspects—not just time-based media works—it is essential to consult the artist while they are still available. Through installing these works in combination with engaging the artist and their assistants through interviews, questionnaires, and email exchanges, we learn about the core concept of the artwork and capture how an installation may or may not change in future iterations. And VoCA has been so instrumental in teaching conservators and curators in the art of interview methodologies—over the last six years, VoCA trained over 450 conservators through their Artist Interview Workshops, which is amazing! I attended a workshop held at the Albright Knox Museum in 2014 during the ANAGPIC conference, and I found it very useful in shaping my interactions with living artists.

But still, when I first started working with you, it really took me out of my comfort zone, as training in time-based media conservation wasn’t available in my graduate program. A big difference was learning to use your Documentation Model for Time-based Media and to adjust to cross-disciplinary and cross-departmental workflows within the larger museum. It was very different than my previous experience in objects/sculpture conservation labs. It took a few months of practice with artworks in the collection to feel more comfortable.

Phillips: And I believe one of the key qualities of a time-based media conservator has to be the ability to find comfort outside of one’s comfort zone. In time-based media conservation, you never seem to reach the point where your experience and expertise makes you a true expert, even after more than a decade in the field. With an ever-expanding landscape of technologies and rapidly evolving conservation practices, there are always more things you don’t know than things you do know. You really have to commit to perpetual learning. And in my opinion, a continuous immersion in practice—conservation practice, but also art production practice—is the only way to stay on top of the rapidly developing discipline.

This is why museums play such an important role in providing training for time-based media conservators. The research and development happens in practice. And museums offer unique access to real artworks; living artists; technical infrastructures in our media conservation labs; real-world acquisition, exhibition, and loan scenarios; and practitioners’ mentorship.

Nichols: At the Guggenheim, you have been so committed to educating emerging time-based media conservators—but tell me, what’s in it for you? Can you speak about the role of interns and fellows in the Guggenheim lab?

Phillips: The Guggenheim Conservation Department has a long tradition of training conservation students and graduates. But over the years, time-based media conservation at our museum has become such a busy operation that we simply couldn’t accomplish all of our projects without a steady stream of graduate interns and fellows. I like to have at least two interns or fellows at any given time, and preferably over one or two years. As you know, it takes some time to introduce emerging conservators to time-based media, which they have rarely had any exposure to. Ideally, of course, I would only take on candidates that have academic training and practical experience in time-based media conservation. But until NYU implements its time-based media curriculum in the Fall of 2018, there is no training in the US and I am happy to consider applicants with a more general background in contemporary art conservation, an open mind, and a deep interest in learning about time-based media.

Fellowships are also very important to support our research and development of new conservation practices. Our current fellow Jonathan Farbowitz, for example, a graduate from NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program, was specifically hired to focus on the 20+ software and computer-based artworks in our collection. His engagement is part of our initiative to “Conserve Computer-based Art” (CCBA), which aims to examine and preserve all of these works in the collection, research selected case studies in depth, and implement new documentation, treatment, and acquisition practices at the museum.

As an integral part of this initiative, we also collaborate closely with faculty, students, and graduates from NYU’s Department of Computer Science. Our interns and fellows work closely with the computer science students and graduates who analyze our collection as credited research, intern with us, or are hired by us for programming and documentation tasks. I like to foster an interdisciplinary team culture in our lab that helps us to think outside of the box and nurtures innovative thinking. Between our daily work and our many exchanges with colleagues, guests, and contracted contributors, the lab has really become quite a hub for media conservation in New York City and beyond.

Nichols: During my time at the Guggenheim, seeing how many visitors we got at the media lab really gave me the sense that time-based media conservation is rapidly gaining importance on a global scale. I helped give what must have been dozens of tours, and we presented our projects to visitors from all over the world: conservators, artists, collectors, curators. I also loved our exchange meetings, for example with Eyebeam’s artists in residence. It was great to see them present their latest art projects with technologies we haven’t even heard about yet, and to then engage with them in discussions about the implications of collecting this kind of art. For many of the artists, it was the first time they had considered the conservation or long-term accessibility of their works.

And of course I felt lucky that I was able to contribute to one of our CCBA meetings in the lab, where I co-presented my work on the Guggenheim’s new commission of Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Can’t Help Myself (2016) to an audience of invited colleagues from a range of New York institutions.

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu Can’t Help Myself (2016)

Can’t Help Myself is comprised of an artist-modified robot which utilizes custom computer code to identify a blood-like liquid on the exhibition floor and to contain it around its base with swipes of an attached squeegee. As the robot rotates to target the flowing liquid, it completes dance-like movements and gestures with its arm.

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Alexandra Nichols (left) works with computer scientist Jillian Zhong (right) to document the behaviors of the custom-programmed robotic arm and visual recognition system that make up the artwork Can’t Help Myself (2016) by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu.

Photo: Esther Chao © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

I am very happy that I had the opportunity to collaborate with computer science graduate Jillian Zhong to analyze and document Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s artwork, Can’t Help Myself. This was such a rewarding project. I had never worked with a computer scientist before, and I think we both learned so much from each other. Jillian’s ability to connect and “talk shop” with the engineers who programmed the artwork was instrumental to our understanding of how it ran, and my experience documenting complex installations helped identify essential information that needed to be transcribed for reference the next time that this artwork goes on exhibition. When we combined our skillsets, we were able to understand and capture this new acquisition that neither of us would have been able to tackle on our own. This was also my first experience working with newly commissioned artworks, which often undergo last minute tweaks during the installation period. To observe and be a part of the artwork production process was particularly exciting.

Phillips: You also dealt with the acquisition and documentation of several live performance artworks and you developed a special passion for processing and documenting these new acquisitions.

Nichols: I honestly had never thought much about what goes into collecting and exhibiting live performance before last year, but I was fascinated by it! One of my favorite experiences was with the performance of Amalia Pica’s Asamble (2015). Working closely with the artist in the weeks and days before the Guggenheim’s performance provided me with invaluable insight into what aspects the artist considers to be most integral to the artwork. Before my fellowship, I admit that had a pretty naive view that collecting performance art meant displaying ephemera or showing video documentation of a past performance. But performance artists in recent years have increasingly created works that are meant to be re-performed by hired performers and that can live—in principle—independently from the artist. The concept of lending performance art was completely new to me, but helping facilitate this was an engaging experience. I had to really think about how to clearly communicate to the loaning institutions how this artwork should be performed.

Amalia Pica, Asamble (2015), as performed at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in May 2017

In Asamble, performers carrying chairs enter a public space in a single-line formation, and begin to arrange in seated circles. Just before the circle is completed, the first person in the group stands up, and walks to another area, and starts to form another circle. The performance is a commentary on the difficulties faced by grassroots organizers and protest groups.

Photo: Enid Alvarez © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Phillips: Has the exposure to time-based media conservation changed the way that you think about and approach other works of contemporary art?

Nichols: I guess I am more aware that the way I am experiencing an artwork may be different than the next time I see it installed. So sometimes I think about how the artwork may have been presented in other exhibition spaces and how it may be shown again in the future. I think I am also more cognizant of any equipment that is used to display an artwork, so I look at how something is displayed in addition to what is being displayed.

Phillips: Do you feel that this one-year practical training at the Guggenheim equipped you for your new position at The Met?

Nichols: Of course there is still so much I have to learn, but I feel that my time at the Guggenheim gave me a solid basis that allows me to operate. I participated in all aspects of the acquisition, exhibition, and lending of artworks. As my fellowship progressed, and with the mentorship of the whole time-based media team, I was exposed to so many different types of artworks and situations and gradually became more and more able to work independently.

And now is such an exciting time to be at The Met, as there’s a lot of enthusiasm and support for addressing the needs of their fast-growing time-based media collection. I’m amazed at what Nora Kennedy, the Photograph Conservation Department’s Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge, and the Department of Photographs Collections Manager Meredith Reiss have been able to accomplish without dedicated time-based media staff here at The Met, especially considering the fact that they have full workloads and responsibilities in addition to those pertaining to time-based media. For example, The Met has a large, cross-departmental TBM working group that is hosting public lectures on TBM topics. They have also commissioned Glenn Wharton to conduct an assessment of the Museum’s time-based media collection and practices in early 2018, and contract conservator Christine Frohnert has been providing assistance on special projects, such as creating conservation documentation for the exhibition The Body Politic: Video from The Met Collection (June 20 – September 3, 2017) .

At The Met, Alexandra Nichols and photograph conservator Nora Kennedy document audio/visual equipment utilized in the exhibition Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists.

Photo: Mollie Anderson © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As part of this growing momentum I am The Met’s first postgraduate fellow dedicated to time-based media conservation, and thus the first person able to devote full-time attention to the documentation of the 275 artworks that comprise their collection. I have had a lot of documentation training at the Guggenheim and am now implementing your Identity Reports and Iteration Reports here at The Met. I am sure that questions will arise, but as you know, the TBM conservation community in New York is very close, and I feel that I have a really good support system here.

I do wish that my graduate studies could have provided a foundation in the history of technologies used in time-based media artworks, and experience with the production of video and software-based art. I also would have benefitted greatly from training in identifying common condition issues, in the same way that objects or paintings conservators learn how to identify issues and damage in the artworks they treat. Since graduation, I have supplemented gaps in my knowledge by consulting with digital preservation literature, attending conferences and workshops, and practicing with video editing software. I am very thankful for the research and travel stipend provided to me in my fellowship at The Met, which has allowed me to travel to and consult with different institutions with time-based media conservation labs. Hopefully, with time-based media being introduced as a specialization option at NYU’s conservation program, the next generation of TBM conservators will receive this academic training in addition to practical training during their graduate internships.

Phillips: I am very optimistic. NYU’s Conservation Center invited a number of museum practitioners to their TBM curriculum planning committee, and as a cross-institutional team we came up with a detailed list of required skills that future time-based media conservators should be acquiring through coursework and practical experience. This includes all of the points on your training wishlist and more, while ensuring the contextualization of the TBM curriculum within the broader discipline of fine art conservation.

And just like in traditional conservation, hands-on practice will always be integral to conservation training and the museums here in New York will play a crucial role in supporting NYU’s TBM education. I am looking forward to welcoming a steady stream of well-trained, emerging time-based media conservators to the Guggenheim Conservation Lab!

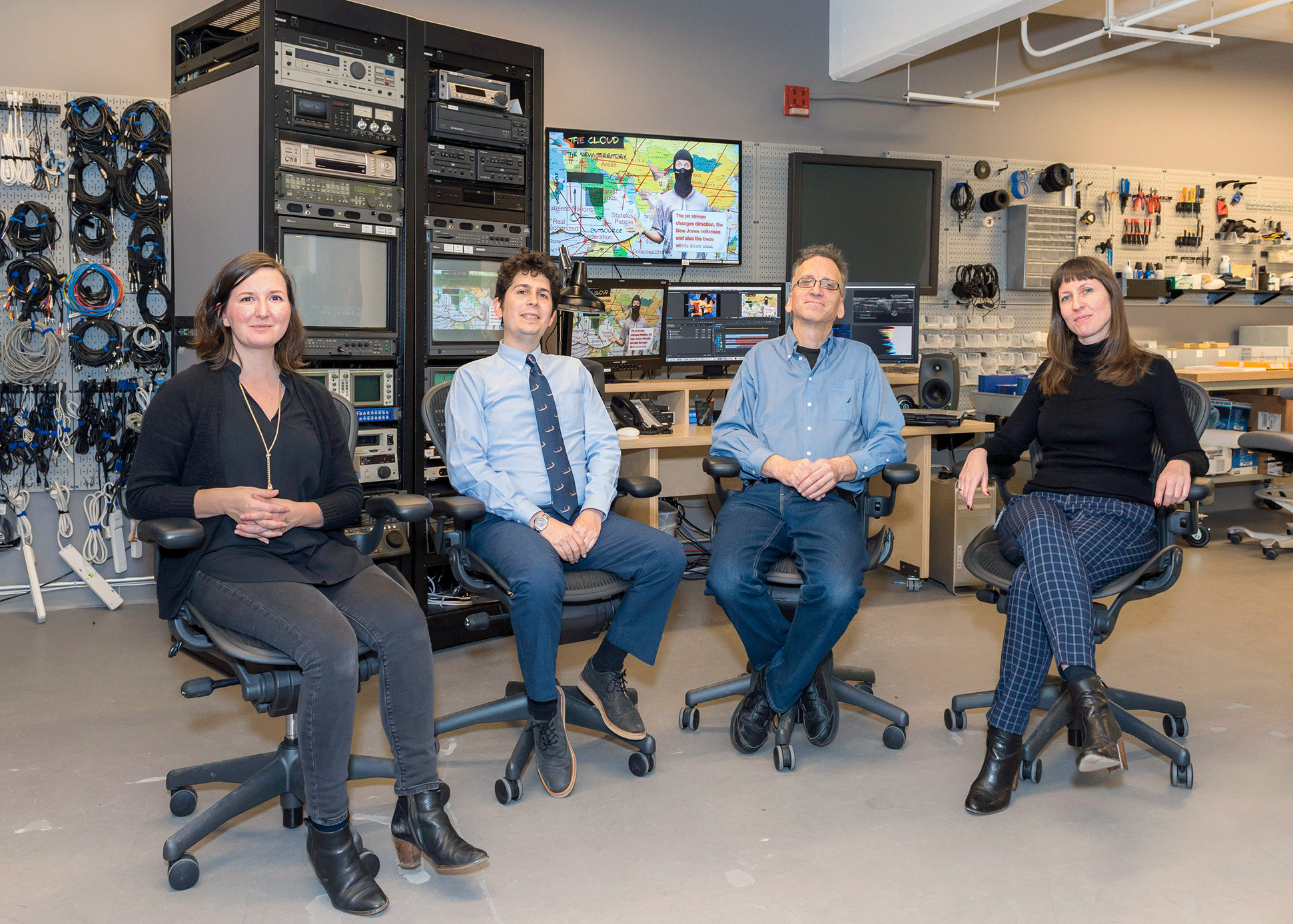

The Guggenheim’s time-based media conservation team during Alexandra Nichol’s one-year fellowship (from left to right): Alexandra Nichols, former Samuel H. Kress Fellow for Time-based Media Conservation, Jonathan Farbowitz, Fellow for the Conservation of Computer-based Art, Maurice Schechter, contract video engineer and time-based media specialist, and Joanna Phillips, Senior Conservator of Time-based Media.

Photo: Kris McKay © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

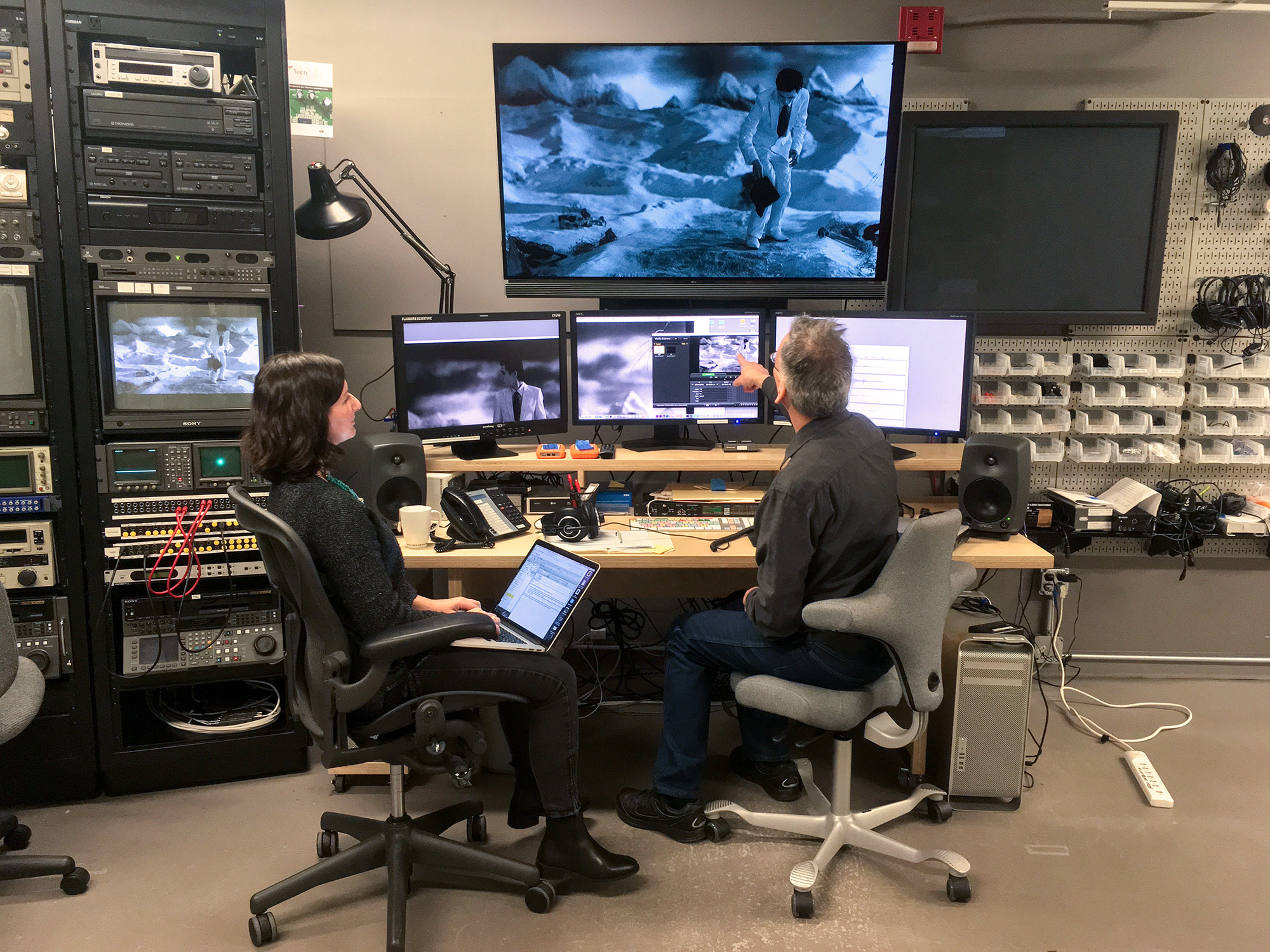

Main image

The viewing station in the Guggenheim’s time-based media conservation lab.

Here, former Guggenheim fellow Alexandra Nichols collaborates with video engineer

Maurice Schechter on assessing the condition of a newly acquired video artwork.

Photo: Joanna Phillips © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum