THROUGH THE SIEVE AND THE LENS OF SCHOLARSHIP

The Jay DeFeo Foundation

Robin Clark: Leah, shall we start with a brief description of the Jay DeFeo Foundation?

Leah Levy: The foundation was established to preserve DeFeo’s artworks, further their public exposure, and more broadly encourage the arts. It is currently governed by three trustees: Janie A. Green, Diane B. Frankel, and myself. I am also the executive director.

Clark: How did you become acquainted with Jay DeFeo?

Levy: When I first met Jay DeFeo in the mid-1980s, she was at a point in her career and life that was relatively unique for her. She had a full-time position as a painting professor at Mills College and wasn’t struggling to make ends meet for the first time in decades. She was able to step back and think about her work in relationship to the larger culture, what unrealized ambitions she had for it and how to achieve them. And she was interested in working with someone to help her enhance the understanding and recognition of her art. I was working with a few artists as an advisor at the time, using the experience I had from directing a gallery and from being the founding curator of the nonprofit Capp Street Project. It was the painter Squeak Carnwath who introduced us.

I knew that in order to be effective, I had to become an expert in her artwork. I had to understand its context and experience it close up, so that I could serve as a liaison between the studio and the outside world. On some level, you need to fall in love with the work, so you can communicate that interest, passion, and knowledge—and I certainly did with Jay’s art.

We created a plan of regularly looking at the work together. She told me the history of her artmaking and a lot about her life. They were integrated and entwined for Jay. That’s where our professional relationship began.

Jay was concerned that there weren’t significant exhibitions of her work in museums and that it wasn’t being considered nationally. We understood that the job was to build appreciation for her work in the culture and in history, and to do that, the context for her art had to be revealed (both in terms of where it came from and what was contemporary that related to it). It was also important to make sense out of the complex breadth of her work. It was never easily categorized—a strength in and of itself, but sometimes a conundrum for people coming to it.

Clark: So in the early days of working with her, what qualities in her work really drew your interest?

Levy: My attractions to it were as varied as her work, and at the time, in the mid-eighties, her work was incredibly varied. Often there would be very delicate lines and a handling of materials with exacting care, which appealed to my love of drawing and the traditional notion of line. Those marks were then opposed, often in the same work, with energetic, expressionistic expanses. There would be perfectly crafted, dense hard forms and edges and then gestural diaphanous spaces with flowing movement; a contrast of mat and shiny, of flat and layered textures. Almost all her works hold opposites that come to resolution in the finished work. So I think the richness and the complexity, above all, drew me in. Jay insisted that every mark mattered at the same time that she welcomed and incorporated elements of chance—a precarious balance that provides incredible energy to her art. So the work spoke to me in a profound way. It was challenging and unlike anything I could categorize. I still struggle to speak about it succinctly.

Clark: I’m wondering if that has changed over time.

Levy: Yes, because the more I know of her work, the more I understand the powerful threads through the disparity in her art. There’s a restlessness, a curiosity, a flow of hers that may seem inconsistent in the moment, but is profoundly constant over time. Dana Miller’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum and SFMOMA did a brilliant job of seguing through the contrasting periods and finding those recurring but transformed ideas.

Clark: I was going to ask you about the establishment of the trust, which became the foundation.

Levy: Jay wrote a will in the mid-eighties, when she was in her mid-fifties, which is very young for an artist to do this. The will did two things. It granted the money that she did have to what became known as the Jay DeFeo Prize at Mills College, which is an annual juried award for a graduating MFA student, to provide funds to help them continue making art when they are out of school. She herself had a traveling grant from the University of California at Berkeley that was very important to her development. And I think that was the inspiration for the Mills endowment. It’s an ongoing expression of her support for young artists.

Entirely separately, the will created a private trust for all of her artwork and her archives and named two trustees: her good friend and former student, the artist Ursula Cipa, and me. I had nothing to do with the conceiving or writing of the will, although I did agree to be one of the co-trustees.

The will is totally simple in terms of the purpose of the trust: it says her goal is to enhance the public recognition for her art and to support the arts. Because she was leaving no funds whatsoever to accomplish this, the will allowed for her artworks to be sold for those purposes.

Clark: And when did it go into effect?

Levy: After she died in November of 1989, there was a period of probate, so the trust actually was endowed with her art in 1991. For the two trustees, the job was to increase the appreciation of the work, little by little and over time, by having people see it, and to figure out how to generate income so we could pay for storage and all the expenses that came along with having many hundreds of works—paintings, drawings, tiny sculptures, and more. At that point, we weren’t aware of the importance of the contents of the boxes of photographs and photocopies interspersed in the archives with other papers—works that we now definitely understand are an aspect of her artmaking.

Clark: So, from the beginning, did you have a physical location for the work that you were doing?

Levy: Jay’s work has always been professionally stored at an art warehouse. The location where our day-to-day work happened at first, where the files were kept, was my house, and the financial records were at Ursula’s, because there were no funds for renting a separate office space. It wasn’t until 2003 that we had an office, and about the same time Michael Carr, our archivist, came on board and still works at the foundation. Those were two huge advances.

Clark: Can you talk a little more about the foundation?

Levy: I should step back and clarify that Jay’s will set up a private trust, which means it wasn’t a foundation; it wasn’t a 501(c)(3). But we knew that Jay had a charitable intent. So eventually we applied for and were granted 501(c)(3) educational, charitable foundation status.

That didn’t change how we thought about some things, but it did significantly alter our focus toward the charitable purpose. When the Jay DeFeo Trust became a foundation in 1997, we understood there were different rules, and we had to think first of how our decisions married with that nonprofit mandate. We actually didn’t change the name formally to Foundation until relatively recently. We lingered on the name of the Jay DeFeo Trust, because Jay had used that term in her will. But then we decided to make it clear that we were a nonprofit and to underline our sense of community with other artist-endowed foundations.

Part of the charitable framework is to educate the public about Jay DeFeo’s work. Because we are small, we’ve had to develop incrementally. We couldn’t afford to do everything at once. The work has been slow and steady over time. We have just completed transcribing all of her journals, key letters, interviews, and lectures, and we’re now correcting and editing those transcriptions, so they will be available to scholars or others with a particular interest soon. We don’t have a study room, we’re not a study center, but we do welcome—by appointment—researchers who have a working project.

Clark: It’s wonderful. You just described the recent transcription of journals and interviews, but what other kinds of work have you done?

Levy: From the beginning, for the probate court, we catalogued all of DeFeo’s work that was understood as art. Since then we’ve set up an extensive in-house database that at some point—just a gleam in our eye at the moment—will serve as the basis for a catalogue raisonné. We have professionally photographed a large portion of the work—although each work, of course, has a visual identifying record. We have also commissioned condition reports and conservation for many works. And we have partnered extensively with institutions and galleries on exhibitions, almost all of which have had accompanying publications with scholarship. In addition to survey shows, we’ve encouraged smaller, focused shows, looking deeply at one aspect of the work. In a retrospective, you might see one or two examples of many periods over a lifetime, whereas a focused show can offer more depth of particular period, theme, or medium.

We have actively invited and encouraged scholarship every step of the way. We’re particularly interested in materials and process. Now that we have digitally archived Jay’s writings, we are able to search more effectively for what she says about her process; how she thought about, experimented with, and used materials; and how her ideas blossomed and morphed through the dictates of those sometimes unconventional materials. Her work was entirely organic and very experimental, even as every mark had to mean something and play a specific role in the whole of the work. Her use of materials is a fascinating portal into her art.

We’ve sponsored gatherings with other artist foundations. We’ve funded museum conservation of DeFeo’s work and have also made grants to other 501(c)(3)s. These are quite modest compared to more largely endowed fellow foundations, but we’re happy with the support we have offered. We’ve funded quite a few catalogues, especially (but not exclusively) for women artists whose exhibitions would not otherwise be documented, along with a realm of other small grants. We don’t publicize them or solicit applications, but we do make them, which is another thing that Jay DeFeo wanted to do. We hope the growth in the value of her work, both historically and in the market, will allow us to build a more active grant-making program.

Clark: There’s a big difference between being able to have a show and having a show that’s documented with a publication. You’ve identified a place where you can make, I think, a big impact.

Levy: Yes. And in every case, there’s scholarship, too. It’s taking our procedure with Jay’s work and making it possible for other artists to have an ongoing and permanent record of an exhibition.

Clark: In a previous conversation, you described your role as educating the public through “the sieve and the lens of scholarship.” That’s an evocative phrase. Is there anything else about the foundation’s role you’d like to say?

Levy: There are many other avenues to explore in and through Jay’s art—her own influences and how her work has and continues to inspire other artists. We’re particularly interested in giving curators and writers an inkling of the depth of the work that has yet to be carefully considered. We have an extensive website, which is the main entry for the general public. Every work in every public institution is pictured on our website, so people can know where they can see DeFeo’s art.

We are aware of the importance of social media and have someone who works to reach art lookers and scholars through the media. We have a guest commentary program, where we pair an image either with remarks invited from a poet, painter, student, or scholar, or with an excerpt from past writing about the work. That series appears on Facebook, on Tumblr, and we archive those comments on our website. We continue to explore an interactive dialogue with the public and are about to be on Instagram.

Clark: This may seem a bit tangential, but I’m interested in the difference in the reception of Jay DeFeo’s work in the US versus Europe. What are some ways that you’re increasing the visibility of her work abroad?

Levy: We are doing the same things in Europe and internationally that we continue to do more locally. We’re talking to curators regularly. We invite and encourage scholarship and instigate or respond to proposals for focused exhibitions at good art galleries and institutions with accompanying publications. There’s a book by a French scholar in the research phase on DeFeo’s photocopy work, which isn’t well known yet, and we’re talking to a European publisher about the next monograph, which will be on the drawings and we hope will be published in English, German, and Italian to respond to broader interest in DeFeo’s art.

We have a wonderful gallery in Zurich, Eva Presenhuber; and there was a beautiful one-person show in Paris last summer at Galerie Frank Elbaz. We’re finding that people in Europe understand and accept the historic importance of DeFeo’s work. But we still need to make the connections for the general public about the relationship of her work to contemporary artists. An exhibit at the highly respected Le Consortium in Dijon, France, is scheduled for 2018, which will include an exciting list of contemporary artists responding to and dialoguing with a core presentation of DeFeo’s work.

It’s always been a challenge to put people at ease with the extent of variation in her work. There isn’t one, easily identifiable DeFeo look. It’s not “commodifiable.” There’s a slow process of opening up her vocabularies in a way that people can become familiar with them and then can interconnect the works in their own way.

Clark: Could you describe a couple of milestones over your thirty years of working with this material?

Levy: Certainly, the success of the conservation of The Rose in 1995 was a celebratory moment. It is a compelling story about a truly great work of art that unfolded over 30 years, which the book Jay DeFeo and The Rose reveals. Having The Rose visible, having this glorious work for people to actually see instead of to mythologize, was a very key moment. Another obvious milestone was the retrospective organized by Dana Miller at the Whitney Museum in 2012, and the catalogue that accompanied it. It was the first opportunity for the public to explore a full range of her art, and people continue to make glowing comments about that exhibit and about the essays in the book.

Another important highlight was the revelation of the extent and the importance of DeFeo’s photographic work, which she didn’t speak about much when I knew her. The Foundation began to exhibit those works in 2000 and they continue to be studied. In some ways, they are like drawings to a sculptor—not an isolated area, but interrelated in all phases of her work. And now we are deep into examining the extensive body of photocopies that are also interwoven through the narrative of her art.

Clark: So what are some of the challenges facing the foundation at the moment, and maybe artist-endowed foundations more broadly?

Levy: The whole nature of the relationships between institutions, museums, foundations, galleries, media, and the public is changing very rapidly. The question of how we can continue to maintain quality and excellence in images and information in this time of immediate access through the digital world is an ongoing consideration. How do we make sure that the images out there are the best possible ones, rather than poor copies? How do we use copyright to protect from inappropriate commercial use while not hindering the free flow of information and ideas? There’s a strong movement among artist foundations to loosen up rights for scholarly and educational uses. The College Art Association’s initiative on fair use is something all of us are paying attention to and many of us are supporting. Still, we are fiduciaries, responsible for the proper care and representation of the artwork while also facilitating its broad dissemination.

Another real issue is having people actually look at the art itself. We hear from students writing master’s theses on Jay DeFeo, and when I ask what works they have seen, sometimes it’s almost nothing. We want people to have the true experience of the physical objects. I don’t think we can really control it; we can just make the work as accessible as possible.

Clark: Is there anything more you’d like to say about your goals for the foundation in the future?

Levy: We have dozens of exhibitions still to be done on DeFeo’s work. One opens at Marc Selwyn Fine Art in Los Angeles in November. The focus is on paintings on paper from the Samurai series of 1986-87 and the accompanying book reproduces, along with images of the works in the exhibit, a selection of facsimiles and transcriptions from Jay’s journals. We’re preparing an exhibit for 2018 with Mitchell Innes & Nash in New York on DeFeo and Surrealism, which promises to be illuminating. Hosfelt Gallery in San Francisco is planning its third major show, and there’s an exhibit about DeFeo’s jewelry and related tiny sculptures and drawings that we’re starting to work on. We’re talking with a curator about a survey of the photographs and photo collages, and there’s another proposal for a photocopy exhibit. All of these mean deeper scholarship and more access to the work.

Looking at a more international audience is another big piece. We can tell from the analytics of people who visit our website and social media that there is large and growing international interest.

Clark: What is your involvement with other artist-endowed foundations, and what advice might you have for someone who might be considering doing this kind of work?

Levy: There’s a hunger among artists and foundations to have community and to address and ponder issues together. The Aspen Institute’s Artist-Endowed Foundations Initiative, whose publications are available online without charge, is a fabulous resource, and there are some other books and initiatives. It’s a field that is seen as a growing force in grantmaking and people want to get it right. My advice is to understand what the best vehicle is for each individual artist and situation, to not automatically assume that a foundation is the best goal. It makes sense for some, but it really isn’t right for others. I also think that many family attorneys and accountants, no matter how trusted, are not necessarily the right professionals to consult when exploring the field. An expert in nonprofits should also be consulted for advice. Access to those already involved with foundations, created by both living and deceased artists, is more possible than ever. Anyone who wants to dip into it can find resources and people to talk with. We are one.

Clark: Would you recommend any resources beyond the Aspen study?

Levy: The first book I had on the topic was Artists’ Estates: Reputations in Trust, by Magda Salvesen and Diane Cousineau. An interesting model to consider is the Artists’ Legacy Foundation in Oakland, California, which was created with the premise of artists joining their art and financial resources to steward their artwork and legacy, educate the public, and make grants to other artists. As government funding recedes, art foundation funding is more crucial than ever to artists and institutions. It’s a fast-changing and multifaceted field built on the vision, creativity, and commitment to philanthropy of artists. It’s wonderful work.

Further Reading

For more information about The Jay DeFeo Foundation, visit www.jaydefeo.org.

For more information about The Aspen Institute’s Artist-Endowed Foundation Initiative, visit www.aspeninstitute.org.

Dana Miller, Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2012).

Jane Green and Leah Levy, eds. Jay DeFeo and “The Rose” (Berkeley: University of California Press and Whitney Museum of American Art, 2003).

Jay DeFeo, Jay DeFeo: Works and Notes (New York: Christine Burgin/Marc Selwyn, 2016).

Available through info@marcselwynfineart.com

Magda Salvesen and Diane Cousineau, Artists’ Estates: Reputations in Trust (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005).

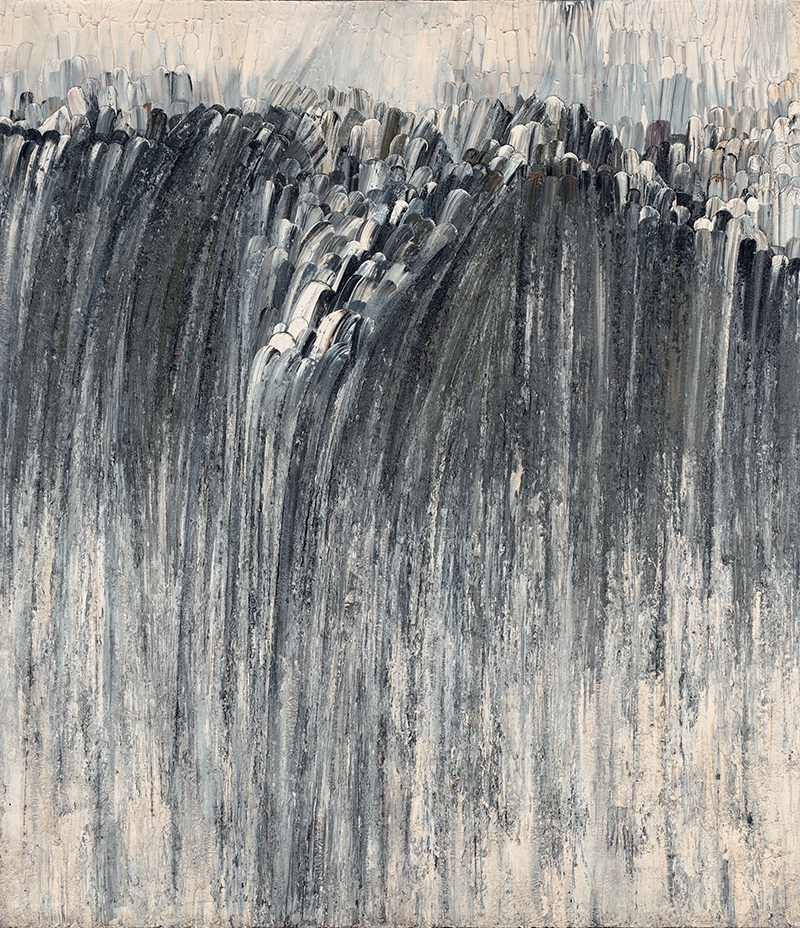

main image:

Jay DeFeo, Dove One, 1989, oil on linen, 16 x 20 in.

© 2016 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo by Ben Blackwell