The Culture of Nature

Mark Dion’s work explores systems of classification and cultural assumptions inherent in the fields of archaeology, art history, and natural history. He frequently collaborates with science and art museums, and seeks out colleagues who are keen to engage in spirited inquiry across disciplines. Situating his practice at the intersection of critical theory and fieldwork, Dion sometimes works as a curator and stages tableaux utilizing his extensive collection of naturalists’ tools. On a rainy day in May, Dion toured Robin Clark through an exhibition at the Drawing Center titled Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions and reflected on the legacy of celebrity naturalist William Beebe.

Robin Clark: Would you describe the genesis of Exploratory Works, and how you came to curate it collaboratively with Katherine McLeod and Madeline Thompson?

Mark Dion: I have been remarkably fortunate to work with these two gifted and insightful scholars. Madeline is the librarian and archivist of the Wildlife Conservation Society located at the Bronx Zoo. The paper archives and thousands of photographs and artworks from the Department of Tropical Research are all in her domain. She knows more than any living person about the extent of this material. Katherine I have known for quite some time since her roots are in the visual arts field and our interests overlap. She is an environmental historian focusing on the history of the culture of field biology. She first encountered the amazing William Beebe when she was working at the New York Aquarium many years ago. We all came to be fascinated with Beebe and the Department of Tropical Research independently and then discovered each other.

My own interests in William Beebe emerged in the early 1990s when I began to work on the topic of tropical rainforest ecology and the biodiversity crisis. I read pretty much all the books I could find on neotropical forests. There was not much, so I started to work my way backward through the history of science writing. There I discovered the remarkable body of work by Beebe on jungles and marine life. I knew he had been based at the New York Zoological Society (chartered in 1895, the Zoological Society changed its name to the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1993) and I boldly trekked up to the Bronx and pressed Madeline’s predecessor to show me the archives. I very much wanted to develop a book project around the material; however, the climate at the Wildlife Conservation Society was not quite right. It took decades and the vision of Madeline and Katherine to be able to realize the project I imagined so long ago.

Clark: The show is organized into several discreet and fascinating passages, including drawings of luminous underwater life, and tableaux of field research equipment. How did these materials come together?

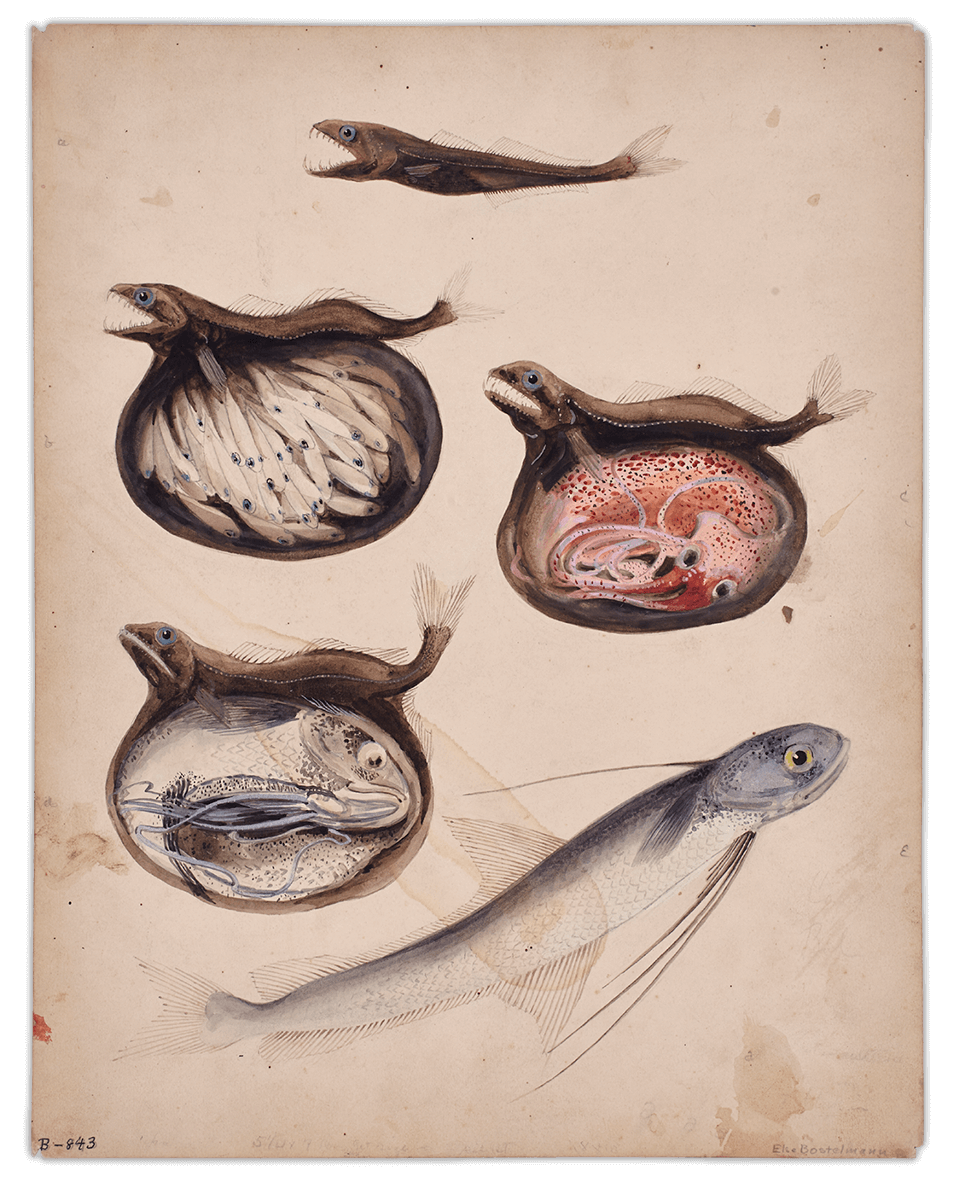

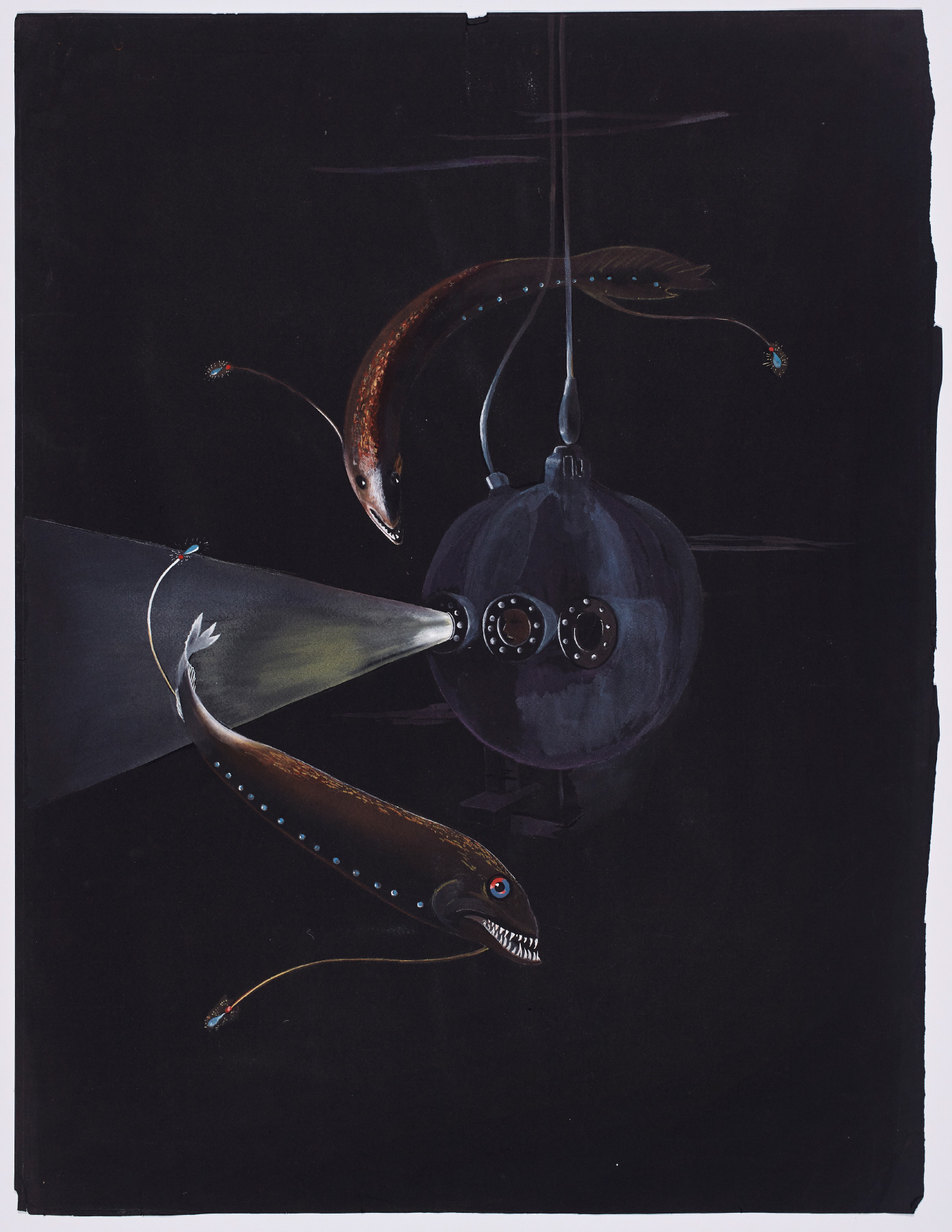

Dion: Our primary agenda was to exhibit the works produced by the artists of The Department of Tropical Research (DTR). These amazing watercolor, gouache, and ink drawings have not been seen for many decades and are a remarkable testament to a moment when artists and scientists worked elbow to elbow to document and understand the diversity of life. We exhibited about 80 works by nine different artists, some of whom, including Isabelle Cooper, Helen Tee Van, and Else Bostelman, worked with the DTR over years.

Katherine, Madeline, and I were drawn to the DTR for specific reasons. First of all, we were excited by the prominence of artists within the organization. From the start, Beebe insisted on the importance of artists within the organization and no major expedition from 1916 to 1964 was conducted without artists. The importance of women, both scientists and artists in the DTR, was also a significant feature of the organization that we wanted to focus on. The DTR fostered the careers of numerous female biologists in an era when women had significant barriers to careers in science.

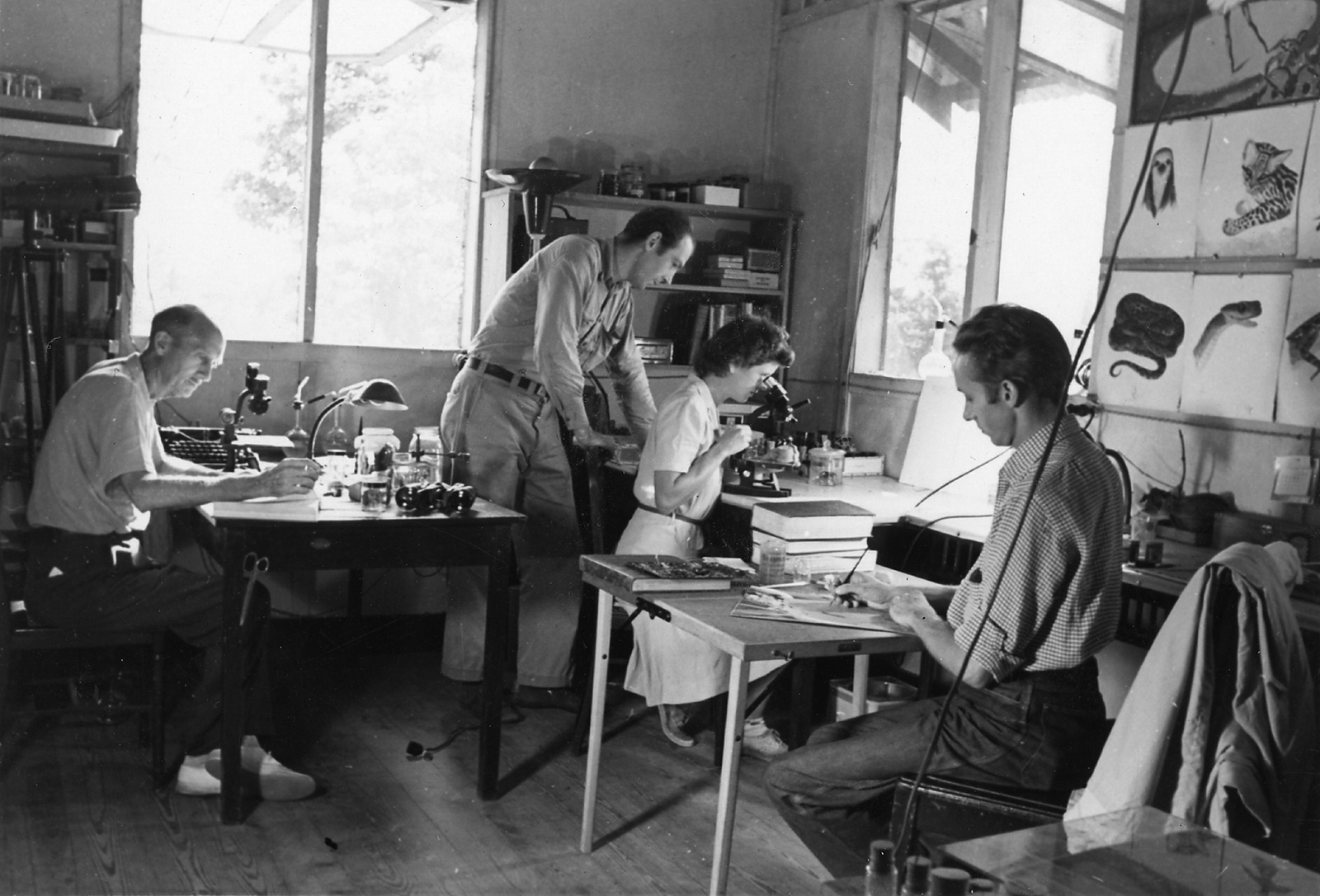

William Beebe and staff at work in a lab in Venezuela, 1940s

© Wildlife Conservation Society

Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives

Dion (Cont.): The DTR and Beebe are poised at this threshold moment between the end of colonial natural history and development of modern field biology in an era of neocolonialism and the expansion of North American extraction industrial capitalism. In the early days of the DTR, the organization piggy-backed on the British Colonial infrastructure and later they collaborated with organizations like Standard Oil. There is much to untangle in the story related to North American imperialism at the twilight of European colonialism and how the sciences were complicit or collaborative in this endeavor.

The DTR’s mission was to study animal life in situ. The vision of the organization was not to bring animal corpses back to some basement laboratory in the natural history museum or university, but to bring the laboratory to the jungle or under the sea. Beebe was insistent about experiencing the animal in their context. This represents the full integration of both evolution and ecology into the academy of the biological sciences.

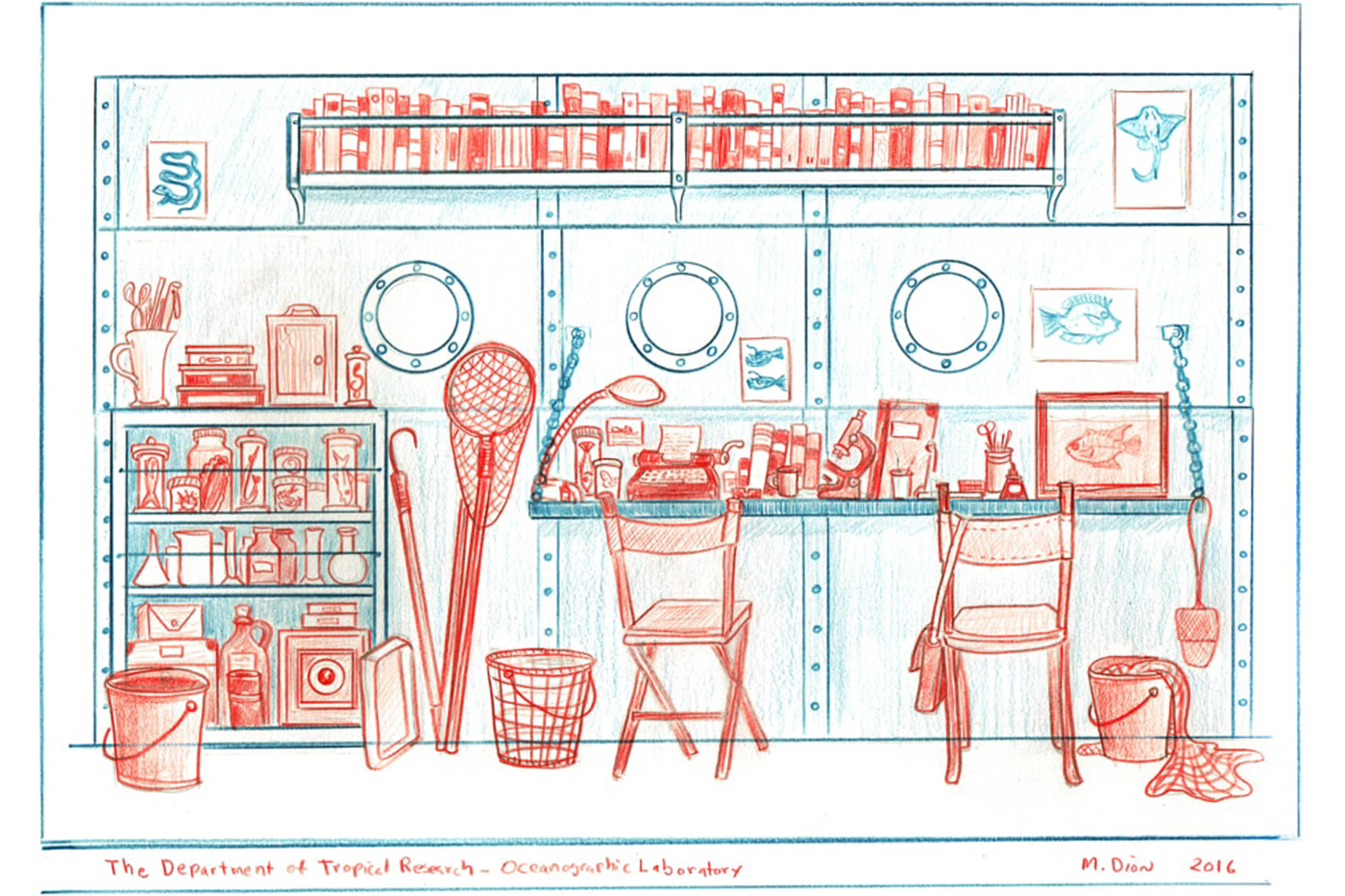

The exhibition takes its lead from the DTR and tries to build context around the drawings the DTR produced. This includes the presentations of artifacts and ephemera, films and photographs of the group and my installations which attempt to reconstruct an impression of the spaces occupied by the DTR team.

Installation view of Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions

Courtesy of The Drawing Center, photo by Martin Parsekian

Clark: A second gallery of the exhibition is devoted to media presentations. Could you discuss these and their relationship to the other materials in the exhibition?

Dion: For Katherine, Madeline, and I it was so powerful to find these films. We had been reading the works and seeing the art of these scientific adventurers for years and all of a sudden here they were in moving images. It was like they were suddenly real and shared time and space with us. It was an emotionally galvanizing moment in the process of the exhibition.

The films demonstrate aspects of the scientific field work but they also are valuable documents of changed environments. The beautiful coral forests depicted in one of the films which feature Gloria Hollister and Beebe underwater were shot in Haiti. Needless to say, there are no such magnificent reefs in existence at the same site today. The film is a testimony to a biodiversity decimated over time.

The surreal aspect of the moving image material was the cue for Courtney Lain, also known as Lady Sea, who composed and performed the music for the films. She composed the score directly to the film we sent her and it adds great imaginative texture to the experience of the films. She is an extremely gifted musician and composer who also happens to share a passion for marine life.

Clark: One of the videos in the show features members of the Department of Tropical Research climbing into “the Bathysphere,” a globe-shaped, pressurized chamber in which the researchers travel to study life near the bottom of the sea. What distinguished William Beebe and his team’s approach from that of his peers at the time?

Dion: Beebe was committed to experiencing the environments that animals lived in, and that was the point of the Barton/ Beebe Bathysphere dive. The DTR were not satisfied to study roughed-up fish corpses dredged from the ocean’s abyss. They wanted to see animals move and interact in ecological situations. Through the tiny bathysphere window they observed bioluminescent phenomena and a number of previously unseen behaviors. Attempting to put the animal’s life in context through experiencing its space is one of the key elements that distinguish the DTR from the old model of natural history focused so primarily on the taxonomy of dead specimens (which of course is still very important).

Clark: Artists were part of the field research teams led by Beebe. How would you characterize the collaboration between the artists and the scientists in DTR? Were the definitions fluid—did the artists consider themselves part of the scientific endeavor? Were the scientists engaged in a creative pursuit?

Dion: Artists were always part of the DTR team. The roles of the work they produced were multifarious. Conventionally the drawings and paintings could be used as illustrations for scientific papers, and they also illustrated DTR activities through slide shows and other public lectures. Work by the artists supported the DTR’s mission to reach a broader public, and appeared in publications including National Geographic and The Atlantic. Doubtless it was instrumental in fundraising. I think the DTR was exceptionally ahead of their time with regards to funding strategies.

From all reports Beebe was exacting in his correction and instruction to the artists. There are lots of notes in which he corrects the artists’ colors or positions. The scientists worked with artists side by side and sometimes changed places. It must have been an extremely exciting and dynamic intellectual environment.

One of my favorite aspects of the book we produced for Exploratory Works is that we were able to reproduce some of the artists’ own writings about their experience. Many DTR staff members were gifted writers and the publication allows them to speak about the experience in their own words.

Clark: You’ve described Beebe as a celebrity naturalist. How did that work, and are there others you might compare him to in the 20th Century?

Dion: Imagine what Jacques Cousteau meant for the 1970s, David Attenborough for the 1990s, or Neil deGrasse Tyson for today: that was Beebe. He was the most well-known American biologist before the advent of television. This was not an accident, he made a focused effort to assure that the work of the DTR was seen and understood by a wide public. He and the team wrote for popular magazines, conducted slide lectures, made newsreels, and did radio interviews, including the landmark NBC radio broadcast from 2,200 feet below the sea.

William Beebe writing while diving in Haiti, 1927

© Wildlife Conservation Society

Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives

Dion (Cont.): Beebe wrote 21 popular books and over 700 scientific articles. His books were often best sellers and he was prominent in the New York City social scene. While he was hanging out with the likes of Rube Goldberg, Katherine Hepburn, Douglas Fairbanks, Errol Flynn, the Roosevelts, and Walt Disney, he remained committed to rigorous scientific discovery and to widely sharing the discoveries of his team as well as instilling a sense of wonder and poetry in the study of nature. Beebe had strong convictions about the primacy of observation in the field. Taking the laboratory to the jungle and insisting on the observation of living things in their natural context is his most valuable contribution to the field.

Clark: The wonderful catalogue that accompanies the exhibition includes several drawings of yours not featured in the show itself. How do you think about your drawings in relationship to the works exhibited in the gallery?

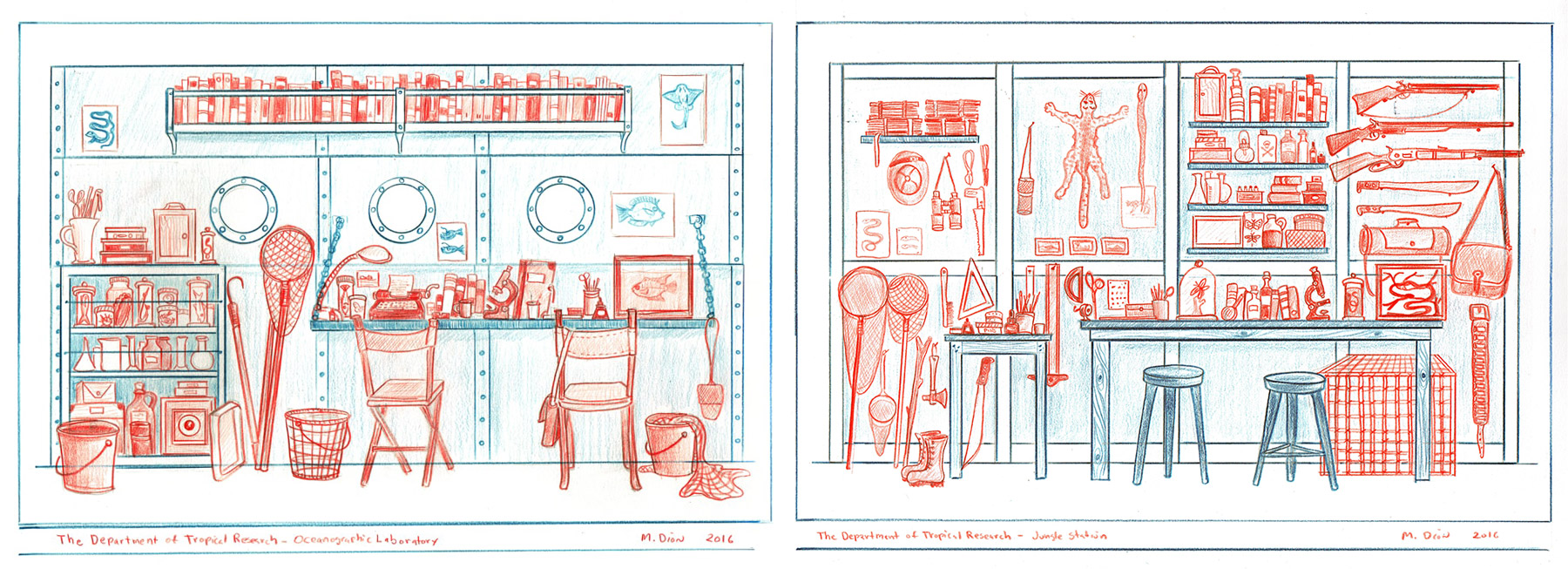

Mark Dion, The Department of Tropical Research-Oceanographic Laboratory and Jungle Station, 2016

Colored pencil on paper, diptych, 11 x 14 in, 27.9 x 35.6 cm (each unframed)

Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Dion: Yes, those are the studies for the two installations which reproduce a sense of the spaces the DTR worked in. One is a condensation of the jungle field stations and the other is one of the maritime laboratories. These drawing helped the Drawing Center team and Madeline and Katherine understand what the spaces would look like. Often my drawings are useful tools to communicate with my collaborators how the finished work will look, and for helping me think through the process of making.

Clark: In an interview with Miwon Kwon you explain that you were an avid natural history hobbyist from an early age and that you went on to study art and develop a conceptually oriented practice in dialogue with artists including Martha Rosler, Joseph Kosuth, and Barbara Kruger. At first you considered these interests as separate but eventually saw how to bring them together. What was the epiphany, or how did you begin to weave these discourses in your work?

Dion: Curiously enough, my epiphany came very much from my experience visiting the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and, after becoming a member there, reading the writing of Stephan Jay Gould, who wrote for Natural History Magazine. I devoured Gould’s books and recognized in them the same critical apparatus that I had been trained in at the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program. Soon I also discovered environmental historians and theorists like Donna Haraway, Alexander Wilson, Andrew Ross, and William Cronon and paired them with scientists like Rachel Carson, Sylvia Earl, and Paul and Ann Ehrlich. Before that my life was somewhat schizophrenic. I had my critical theory friends and my nature friends. During the week I was steeped in Frankfurt School and Foucault, and on the weekend I was camping, fishing, and birding. While it seems obvious now, it took me some time to realize that that the sharp critical tools I had been honing could actually be used to examine the things I really cared about—the culture of nature, and the protection of wild places and things.

Clark: You have expressed an interest in art conservation. Would you discuss the appeal, and how it may have informed your work?

Dion: I worked as a fine art conservator the years I attended school in New York. It was a challenge to juggle a 30-hour a week job with school and a social life. I think I was affected by witnessing the influence of the market on the art works we dealt with. The studio I worked with did not have the most scruples. While this in no way represents the standards of art museum conservation, it had a profound influence on my understanding of the instability of history under the pressure of contemporary values. This was something very much in the air during the Reagan administration when history was being rewritten with a conservative pen.

I still think about conservation and have a lively exchange about these issues with my friend Peter Miller at the Bard Graduate Center. They commissioned a work from me which is a conservator’s cupboard.

Clark: Following the Drawing Center show, you returned again to your own field research. What can you tell us about your upcoming projects?

Dion: I have two significant survey exhibitions imminent. The first is at The Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston and is titled Mark Dion: Misadventures of a 21st-Century Naturalist. This will be my most significant museum exhibition in the US to date, and it covers works from the mid-1980s to today. I am overjoyed to have it in my home state of Massachusetts, with the institution where I saw my first Warhol in 1980. The next survey will be in February 2018 at The Whitechapel Art Gallery in London, an institution I am extremely fond of. This will focus on works produced around the UK, largely in public collections, as well as some important projects from Europe and new things. I am fortunate and proud to be working with a younger generation of curators who are skilled and have razor-sharp critical faculties: Ruth Erickson in Boston, and Daniel Herrmann in London. I tend to get quite close with the people I work with, so I am immensely lucky to have the opportunity to work with these two.

Further Reading

Mark Dion, Katherine McLeod, and Madeleine Thompson. Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions (New York: The Drawing Center, 2017). Available as a downloadable PDF https://issuu.com/drawingcenter/docs/drawingpapers132_exploratoryworks. The exhibition was on view at The Drawing Center April 14-July 16, 2017.

Lisa Graziose Corrin, Miwon Kwon, and Norman Bryson. Mark Dion (London: Phaidon, 1997).