Preserving a “Trans-customary Portal”

Auto Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountain

William (Will) Ray Wilson is a multimedia artist known for blending historical and contemporary elements in his work. Born in San Francisco and raised on the Navajo reservation, Wilson’s art fuses a Navajo worldview with his views on social and environmental issues. As part of the Science and Arts Research Collaborative (SARC),1 Wilson is committed to exploring the intersections of art and technology through his art practice and in so doing has broadened his impact on American Indian arts.2 The Denver Art Museum (DAM) formed a relationship with Wilson in 2013, when he participated in the museum’s Native Arts Artist-In-Residence program. During this residency, Wilson produced a series of photographs of members of local American Indian communities, as well as staff and visitors to the museum, using the historical tintype technique.3 His project, called the Critical Indigenous Photography Exchange (CIPX), sought to counter romanticized, objectifying portrayals of American Indians by western photographers such as Edward S. Curtis, reclaiming a historical technique to portray contemporary individuals.

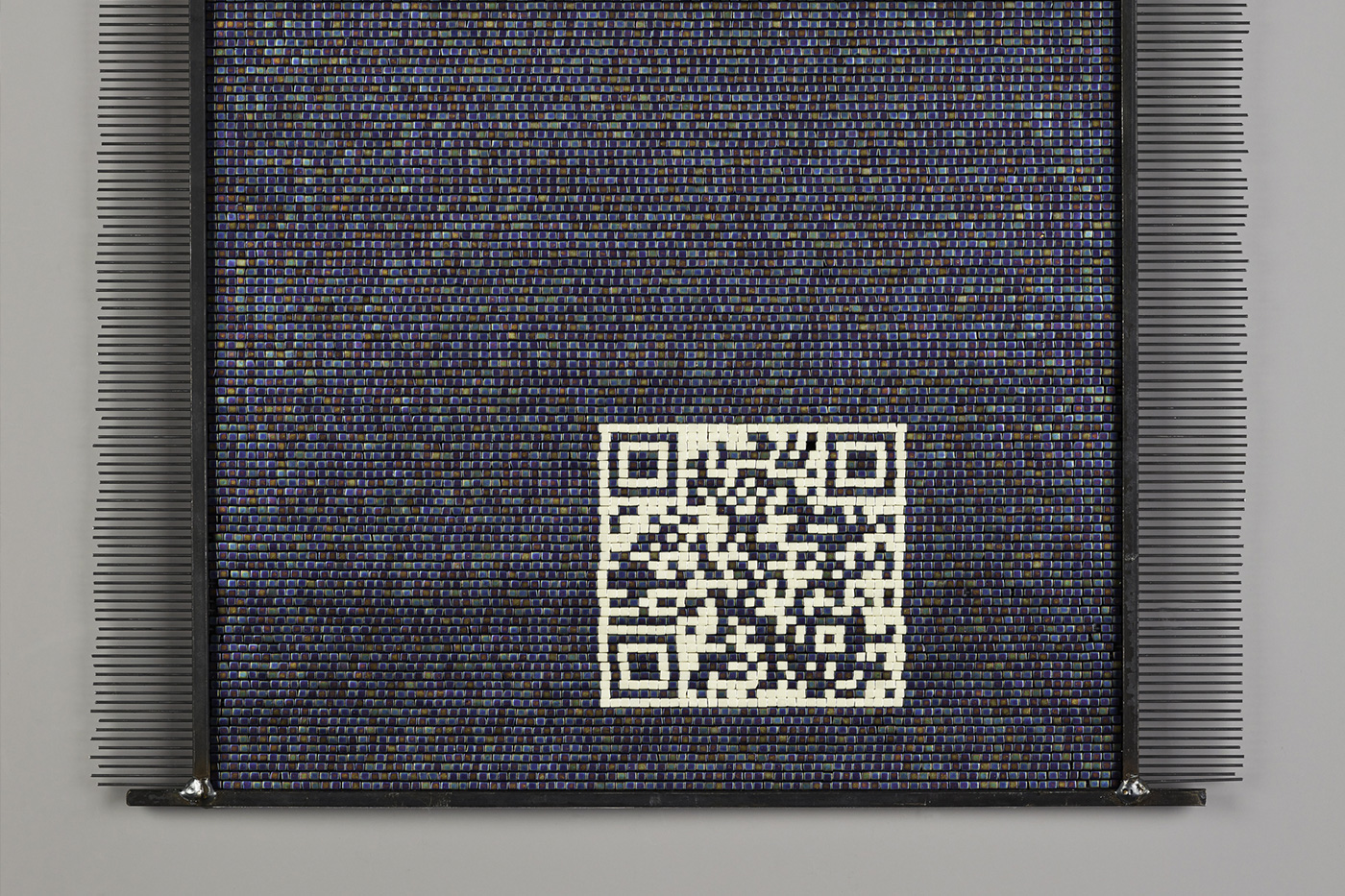

Also in 2013, the Denver Art Museum acquired the series of works by Wilson known as Auto Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountains, which includes four individual beaded panels or “weavings” as Wilson refers to them, Auto Immune Response: East, South, West, and North. These works are a sub-series of Wilson’s Auto Immune Response project, which he began in 2005 as “an allegorical investigation of the extraordinarily rapid transformation of Indigenous lifeways, the disease it has caused, and strategies of response that enable cultural survival.”4 Wilson has explored this series in a variety of media, including photography, installations, glass beads, and video. The four works acquired by the museum are among the first five created by Wilson that include QR codes formed by 4mm square Miyuki colored glass beads.5

By integrating functional QR codes into the four beaded weavings, Wilson converts a two-dimensional art form into a multisensory, engaging experience. Each code, when scanned with a smart device, opens a different video showing Wilson’s Auto Immune Response protagonist in one of the Navajo people’s four sacred landscapes. As Wilson explains in DAM’s gallery text, “The work has focused on a post-apocalyptic Navajo man’s journey through an uninhabited landscape. The character in the images is searching for answers. Where has everyone gone? What has occurred to transform the familiar and strange landscape that he wanders? Why has the land become toxic to him? How will he respond, survive, reconnect to the Earth?”

Each of the beaded panels represents a sacred mountain in one of the cardinal directions. Installed in the Denver Art Museum’s American Indian art galleries, they are arranged as points on a compass with north at the top. The white panel, EAST, was the first work Wilson made in this series and he used a weaving technique that employed 12 lb test Fireline® fishing line as both the warp and weft threads. This work represents Mount Blanca (Tsisnaasjini’—Dawn or White Shell Mountain), near Alamosa, in the San Luis Valley of Colorado. When making the other three panels, Wilson switched his weaving method, replacing the fishing line with steel metal rods that run horizontally through a metal frame and each bead in a row. The blue panel, SOUTH, represents Mount Taylor (Tsoodzil—Blue Bead or Turquoise Mountain), north of Laguna, New Mexico; the yellow panel, WEST represents Mount Humphreys (Dook’o’oosliid—Abalone Shell Mountain), north of Flagstaff, Arizona; and the black panel, NORTH represents Mount Hesperus (Dibé Nitsaa—Big Mountain Sheep or Obsidian Mountain), northwest of Durango, Colorado.

Will R. Wilson (Diné [Navajo], b. 1969), Autoimmune Response: South, 2011-12

Weaving with QR code, 17 x 17.5 x 0.5 in.

Funds from Polly and Mark Addison and Native Arts acquisition fund, 2013.4.1–4 ©Will R. Wilson

Upon acquisition, Auto Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountains immediately raised questions surrounding the longevity of the technological elements. QR (or Quick Response) codes, are machine-readable optical labels that can be interpreted by smartphones and similar devices equipped with cameras and QR code scanner apps. Though used for other purposes as well, QR codes are commonly used to link to websites and are encoded with a specific URL to which the device navigates upon scanning; linking to a new URL via a standard QR scanner app requires a completely different QR code.8

In the context of the Auto Immune Response weavings, this implies that the beadwork would have to be redone in order to point to a different website, and so the URL for the video content cannot change in order for the work to function as originally designed. The QR codes in Auto-Immune Response link to a Tumblr® 9 site set up by the artist to present the video content. Tumblr® in turn links to Vimeo® 10 where the video content is hosted. Thus, the original functioning of the QR codes is dependent on two commercial websites with no guarantee of permanence or longevity. Neither the artist nor the museum can exert any authority over these sites, and so the URLs encoded in the QR codes of the work are not likely to be maintained in the long-term.

Will R. Wilson (Diné [Navajo], b. 1969), Still from video for Autoimmune Response: South, 2011–12

Video, Dimensions variable, duration 2:52

Funds from Polly and Mark Addison and Native Arts acquisition fund, 2013.4.1–4 ©Will R. Wilson

During Wilson’s residency at DAM, the authors interviewed Wilson about his use of technology and views on how the work could be presented once the QR codes no longer functioned in their original capacity. Wilson explained that the incorporation of the QR codes was an embodiment of the trans-customary concept, combing contemporary technology with traditional practices of beadwork and weaving. In the interview, he described a related work incorporating QR codes as “a trans-customary portal to another dimension.”15 He first became interested in QR codes for the possibilities they present for interactivity with a physical object. He said, “The weavings are really meant to be the keys to the codex, the links to the storytelling moment.”16

Wilson also reflected on the relationship of the web to native oral traditions in their subjectivity and shifting nature, and said that it was appealing to him “that [the videos] live out there in that media landscape that’s ever-changing and fluid.”17 However, he noted that the presence of the videos on the web was only of secondary interest to him. Hosting of the videos on the web does not appear to have been a conscious effort to make the videos publicly accessible outside where the work was displayed or to initiate a participatory relationship with the viewer, where the viewer might comment or respond to the artwork online. Instead, Wilson expressed more interest in the relationship between computer technology and pattern-based traditional native practices like weaving and beadwork, analog precursors of computer programming. He noted:

Thinking about technology and the history of technology…was not lost on us. I mean the first computers were based on punch cards that ran automated weaving machines, and so there’s a nice circling back to the technology of weaving and these computational systems that now enable this passage from something that’s built into the weaving of the design to this other landscape that’s out there, that’s on the web.18

Although the Auto Immune Response series imagines what Wilson described as “obsolescence to the tenth degree, where we’ve made ourselves obsolete,”19 the highly contingent and vulnerable nature of the QR codes was definitely not the point for him. In the end, he wants them to continue to function in their capacity as both signifiers of digital technology and technological links between the customary and the new, as well as the present and an imagined future.

Interestingly, scanning the weavings with a QR code reader is not the only way for viewers to access the videos. Wilson also allows the videos to be displayed on a separate display next to the weavings, as was done at the New Mexico Museum of Art when the work was first shown and is currently the case at the Denver Art Museum. However, this display method is really just a practical solution to the problem that not all viewers will have with them smartphones with a QR code reader installed.

In the work’s current installation at DAM, the viewer is thus presented with two options to access the videos: through the viewer’s own smart device or via a display installed next to the panels. QR codes remain a familiar technology, and the link between the panels and the videos can be readily imagined by most, even if they choose to access the videos through the display.

![. Installation view. Will R. Wilson (Diné [Navajo], b. 1969), Auto Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountains, 2011–12.](https://journal.voca.network/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Autoimmune-installation-overall_1200w.jpg)

Will R. Wilson (Diné [Navajo], b. 1969), Auto Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountains, 2011–12, installation view

Funds from Polly and Mark Addison and Native Arts acquisition fund, 2013.4.1–4 ©Will R. Wilson

For the work to remain vital over time, it will be important to enact such a simulation and not take Wilson’s current flexibility on the display method as license to simply show the videos off to the side. An interpretive challenge will be that QR codes (and even smartphones) will seem after a certain point old-fashioned and low tech, or may even be completely unfamiliar. It will be important to avoid emphasizing the obsolete nature of the QR code technology and to allow the linkage between traditional arts and the digital world to prevail. A simulation linking the weavings to the videos via a custom app would explicate QR code technology through demonstration, and a lengthy explanation of QR code technology and its demise would not be necessary. Viewers would still be experiencing the “trans-customary portal”, the link that originally existed between the physical beaded weavings and the digital realm of the videos.

![Viewer interacting with Autoimmune Response: West. Will R. Wilson (Diné [Navajo], b. 1969), Auto Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountains, 2011–12.](https://journal.voca.network/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Autoimmune-West-visitor-interaction_1200w.jpg)

Will R. Wilson (Diné [Navajo], b. 1969), Viewer interacting with Autoimmune Response: West, 2011–12

Funds from Polly and Mark Addison and Native Arts acquisition fund, 2013.4.1–4 ©Will R. Wilson

1 The Science and Arts Research Collaborative (SARC) “brings together artists interested in using science and technology in their practice with collaborators from Los Alamos National Laboratory and Sandia Labs as part of the International Symposium on Electronic Arts, 2012 (ISEA).” http://willwilson.photoshelter.com/about (accessed 5 June 2017)

2 http://willwilson.photoshelter.com/about (accessed 5 June 2017)

3 Other terms for tintype photography are ferrotype and malainotype

4 http://willwilson.photoshelter.com/about (accessed 5 June 2017)

5 The fifth Air Weave work is a woven beaded panel that incorporates two QR codes into a Navajo “Eye Dazzler” rug pattern.

6 http://nmai.si.edu/indelible/william-wilson.html (accessed 5 June 2017)

7 Jahnke, Robert Hans George, “Toioho ki Apiti the Awakening of Creativity: A Pedagogy for Trans-national Art,” International Journal of the Arts in Society, Volume 4, Issue 2, pp.97-112.

8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QR_code (accessed 9 June 2017)

9 Tumblr® is a website that allows users to post blogs with multimedia content, which other users can follow. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tumblr (accessed 12 June 2017)

10 Vimeo® is a website that facilitates the posting, sharing, and viewing of video content by users. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vimeo (accessed 12 June 2017)

11 https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/05/qr-codes-for-the-dead/370901/

12 https://www.searchenginejournal.com/5-reasons-why-qr-codes-are-more-outdated-than-pogs/141958/ (accessed 9 June 2017)

13 Will Wilson, email correspondence, 25 April 2017.

14 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Capacity_Color_Barcode (accessed 9 June 2017)

15 Will Wilson interviewed by Kate Moomaw, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, 3 April 2013. Unpublished.

16 Will Wilson interviewed by Kate Moomaw, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, 3 April 2013. Unpublished.

17 Will Wilson interviewed by Kate Moomaw, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, 3 April 2013. Unpublished.

18 Will Wilson interviewed by Kate Moomaw, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, 3 April 2013. Unpublished.

19 Will Wilson interviewed by Kate Moomaw, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, 3 April 2013. Unpublished.

20 Will Wilson interviewed by Kate Moomaw, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, 3 April 2013. Unpublished.