Picturing the Future

Preservation of the Two-Way LA-NYC Video Phone

“Proclamation: Someday, all human communication will be through video. Or where it’s not it will be as if it were by way of video, just as today most human communication is as if it were by way of telephone.”

– Al Robbins

On January 19, 1979, two groups of artists and students gathered at the AT&T offices in New York City and Los Angeles to exchange their work in a series of informal performances on AT&T’s satellite Picturephone. Referred to by participants as a “video happening,” the Two-Way LA-NYC Video Phone experiment was initiated by Mitsuru Kataoka (1934–2018), Professor of Design and Media Arts at the University of California, Los Angeles with the aim of exploring the non-commercial potential of video phone technology. Kataoka, a central figure in US and international networks of video art and activism, organized the first Video Phone event in coordination with fellow artists Shigeko Kubota (1937–2015) and Nam June Paik (1932–2006), who lived in New York and shared his interest in using new technologies to facilitate collaborative, peer-to-peer communication. A second event followed a month later in March 1979, and the Dickson Media Lab at UCLA continued these experiments with additional artists-in-residence at UCLA into the 1980s. The events highlight a number of lesser-recognized but highly instrumental artists and their interest in video’s transformative social potential. Building on artistic collaboration with television and satellite broadcasts, the Picturephone performances realized the artists’ utopian visions of collaboration, interactivity, and non-hierarchical flows of information [as well as their second order effects]. The recent preservation of the Video Phone as part of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation digitization initiative also points to the particular challenges for stewards of ephemeral, event-based experiments in video.

It is hard to imagine a recent past when widespread connection via video did not exist, and perhaps more difficult still to measure the full impact of this shift in communication. Yet, the implications of video communication on both individuals and society have been top of mind for artists from the earliest stages of the adoption of the medium. When Beryl Korot, Ira Schneider, and Mary Lucier published their introduction to video as an artistic medium, Video Art: An Anthology, in 1975, they intended to publish a second anthology titled Video Communication focused on the work of artists “developing the informational and social aspects of the medium.”1 Although this second volume never came to fruition, it is worth revisiting the numerous experiments in video communication and the ways in which artists envisioned the transformative potential of new technologies, as well as the ways new media could (and should) be employed. Recent exhibitions, such as Signals: How Video Transformed the World at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (March 5–July 8, 2023), capture artists’ vision of video’s potential as a force for political and social change, while also signaling the turning point in the reception of time-based media. The shift from its status as an anti-institutional medium shown in alternative, artist-run, or interstitial museum spaces to an important category of contemporary art has been gradual. However, since the early 2000s, museums and large institutions have been devoting increasingly significant resources, space, and staff to integrate time-based media into their collections.

Many projects that prioritize process and collaborative, community engagement are often overlooked in histories of new media or considered ancillary to artists’ practices. Unlike other pre-internet video and satellite experiments, such as Liza Béar and Keith Sonnier’s Send/Receive Project (1977) and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz’s Hole in Space (1980), the Video Phone experiments are absent from discussions of video and telecommunications networks. In the face of rapid technological obsolescence, there is an urgent need to digitize and preserve tapes documenting under-examined experiments with alternative uses of video that rarely make their way out of artists’ archives to be exhibited or collected by institutions. Stewards at artists’ archives, estates, and foundations play a key role in addressing short-term issues surrounding time-based media, including storage and digital preservation of analog media or playback systems. These smaller organizations–often with direct connections to the artists and intellectual copyright–are strategically positioned to maintain and provide access to work in a timely manner, especially work currently outside the immediate purview of collecting and exhibiting institutions. This stewardship facilitates new research, exhibitions, and programs that enable critical re-examinations of particular artists’ work and a re-evaluations of media histories in the long-term.

Initiated by the artist’s bequest, The Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation (SKVAF) has the mission of preserving and promoting Kubota’s legacy as a video artist, curator, critic and collaborator, as well as advocating for wider, more inclusive histories of the medium. In the effort to make Kubota’s video work and archival material accessible to the public, SKVAF is currently restoring the artist’s complete body of video work, cataloging and digitizing her analog tape library, along with related materials in her archive. While the resources of artist-endowed foundations and estates may be modest compared to larger institutions, entities like SKVAF collaborate with colleagues in galleries and museums to conserve, contextualize, and provide access to Kubota’s materials. However, many small-scale organizations lack an endowment or resources to address rapid obsolescence. The imminent risk posed by deteriorating analog media and display technology necessitates further community-building and collaboration between artist’s archives, estates, foundations, and larger, well-endowed institutions to pool resources in order to ensure the digital migration of these collections. This collaboration is essential to pool resources and ensure the digital migration of these collections. Establishing these relationships will also lay the groundwork for in-depth discussions about sustainable preservation strategies and accessibility.

The primary goal of SKVAF in its first decade is the digital preservation of Kubota’s complete video library. The SKVAF archive houses approximately 1200 videos in various formats, including half-inch open-reels, three-quarter inch U-matics, half-inch Betacams, laser discs, and DVDs, in addition to the artist’s editing and display technology. The media’s content ranges from raw footage of the artist’s diaristic practice and documentation of performances and video programs in New York, to edited single-channel videos and content for the artist’s video sculptures.

The ongoing digitization of Kubota’s tapes, spearheaded by my colleagues Reid and Norman Ballard,2 has made it possible to engage with more examples of video culture from the 1970s and 80s. These efforts have enabled the restoration and exhibition of a core group of Kubota’s video sculptures that resulted in the exhibitions, Shigeko Kubota: Liquid Reality (Aug 21, 2021–Feb 13, 2022), Viva Video! The Life and Art of Shigeko Kubota (March 20, 2020- February 23, 2021), and Red, White, Yellow & Black: 1972-73 (March 7-April 29, 2023), as well as research on additional chapters of Kubota’s under-evaluated diaristic practice, the “Broken Diary” series. Kubota’s tape library is also rich in documentation from Kubota’s tenure as curator at Anthology Film Archives (1974–1982). As curator, she focused on process-oriented, collaborative events and programs that enrich our understanding of artists’ visions of video as both an artistic medium and tool for transforming society. One such experiment located in Kubota’s video archive, and recently digitized by Maurice Schecter and Bill Seery of Mercer Media, includes two, half-inch open-reels featuring documentation of the January 1979 Two-Way LA-NYC Video Phone.

In this case, the two tapes were inspected and cataloged at SKVAF’s archive, where tapes are stored in the artist’s home editing studio. Metadata about the tape, including format, condition, and label notes by the artist, were recorded. After being transferred to Mercer Media, the tapes were re-inspected, particularly for mold or stickiness. Stickiness can be caused by the tape adhesive absorbing moisture from the air. The tapes were then cleaned and, if any issues with stickiness were noted, they were baked in a convection lab oven at 50 degrees Celcius for 24 hours or longer, depending on the condition. Baking causes the moisture in tapes to dissipate. Typically, after baking the tape undergoes a second cleaning process to remove any residual residue. After the tape was successfully cleaned, it was played on the appropriate tape deck in order to determine the optimal signal path to recover the content of the tape, evaluate the needs for time-based correction, and set levels for audio and video going into the computer during migration. Digitization was continuously monitored to check for for irregularities or dropouts over a CRT monitor connected to the computer. It is not uncommon to digitize a tape two or three times to achieve the best results for a new master file. Three digital derivative files were prepared from the analog master: a master preservation file (uncompressed one-to-one copy), a preservation file (10-bit uncompressed), a mezzanine file for editing (ProRes HQ), and an access file for everyday screening and reference (mp4). These file types are not the only options for each level of preservation, and are often determined with the artist or TBM steward according to their particular needs.3 In the long term, SKVAF aims to make Kubota’s fully digitized tape library easily accessible online to students, scholars, curators, artists, and all those interested in Kubota and early video history.

There are at least three extant tapes documenting the January 1979 Two-Way LA-NYC Video Phone event: two reels of raw footage featuring the New York contingent from Kubota’s collection, filmed by artists Joan Logue and Robert Harris, and one tape of edited documentation featuring the LA contingent from Kataoka’s collection edited by Kataoka and Dyke Redmond in 2016 (available on the Dickson Art Center’s YouTube channel).4 Meanwhile, the Getty Research Institute is in possession of one tape from a second call organized by the same group of artists on March 9, 1979.5 Collective authorship and fragmented documentation of the Video Phone happenings have led to the availability of documentation in different repositories. Piecemeal tapes of each event are now co-managed by The Kubota Foundation, the Getty Research Institute, and the Mitsuru Kataoka Estate, allowing researchers to request access to them easily. While this dispersal of located tapes across different collections only offers partial perspectives, it is helpful for researchers to have footage available from various archives to construct a more comprehensive record of the event. Curators and arts educators can also request screening rights to make these materials available to the general public. Additionally, documentation of later calls in the 1980s might exist in other artists’ archives, offering an exciting opportunity for further exploration. Kubota’s and Kataoka’s significant roles in building video networks and impacting local communities underscore the long-term importance of preserving artists’ intentions and voices through interviews in addition to digitization. Interviews with participating artists become a crucial aspect of stewardship in the short term, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of these immaterial video communication experiments. SKVAF aims to conduct oral histories with as many participants as possible, further enhancing the preservation and appreciation of these works. The content of the extant tapes is rich even if it is not comprehensive. The first performance event was informal and playful, with participants taking turns presenting their work in rapid succession because of the call’s one-hour time constraint. Under Kataoka’s leadership, the Dickson Video Lab pioneered experiments with two-way communication technologies that explored the artistic potential of the medium that did not yet exist, exemplified by an announcement about the organization in the fourth issue of Radical Software in 1974: “The entire premise of this laboratory has been to work with persons who have no vested interest in video systems as known today commercially.”

On the first reel filmed by Bob Harris, Kataoka sets loose guidelines for the call but invites all participants to engage in conversation to test the interactivity of the medium.

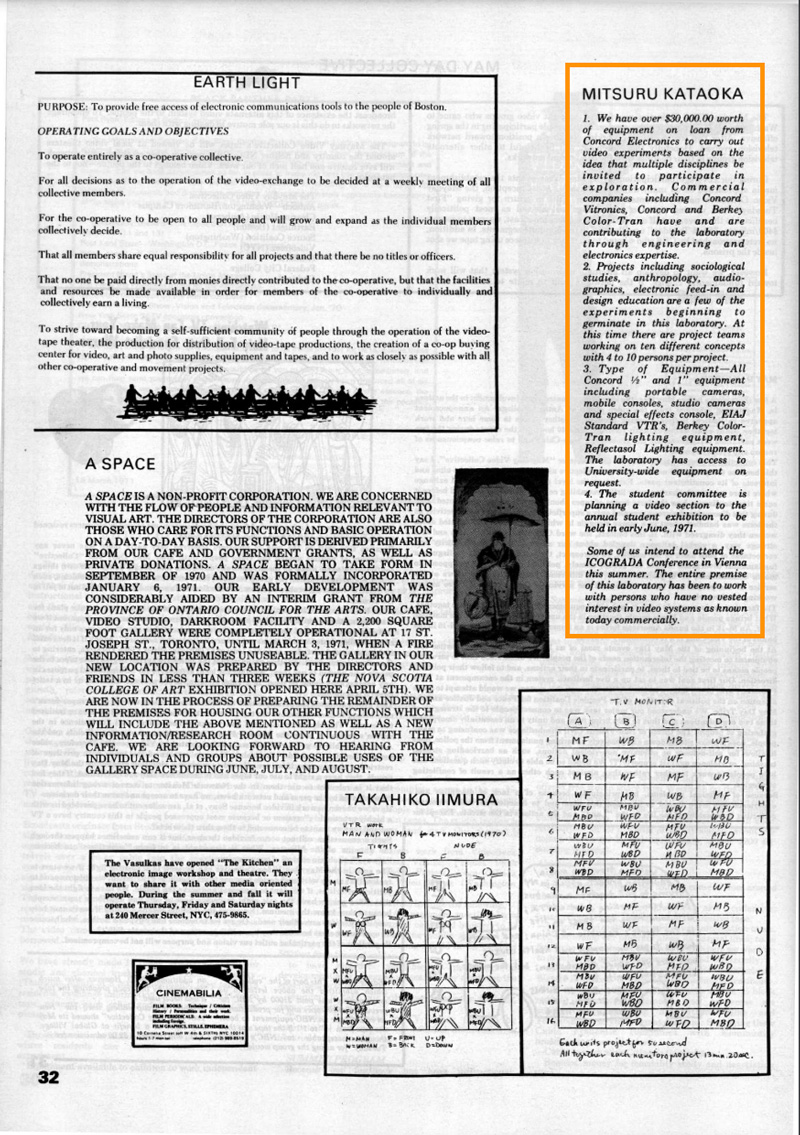

Mits Kataoka welcoming participants of the Two-Way Video, LA-NYC, Video Event on January 19, 1979

Courtesy of Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

© 2023 Estate of Shigeko Kubota/ Artists Rights Society NY

A student named Robin Lasser, performs a piece that blur the distinction between artist and audience. She moves under a camera intended for slide sharing, and the artists in NYC are meant to interact with her image on the screen using the slow scan transmitter. Frequent breakdowns in the video transmission from New York to LA, caused by the artists’ inability to queue the tape with the live video feed, were a recurring issue. Glitches like this forced participants to conduct the performance with one-way video streams and often added to the humor, play, and spontaneity of their conceptual exchanges. For example, the second reel from Kubota’s collection, filmed by Logue, features a fashion show of chic pajamas for video calls coordinated by Paik. Furthermore, questions about sightings in LA from Ay-yo address more serious concerns about how the medium affects the message. The Fluxus-inflected format for the event integrates the roles of audience/ participant as co-creators, while intentional illegibility and tongue-in-cheek banter resist the corporate functions of technology and predict its success for everyday personal use today.

Nam June Paik’s Pajama Fashion show for the Two-Way Video, LA-NYC, Video Event on January 19, 1979

Courtesy of Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation.

© 2023 Estate of Shigeko Kubota/ Artists Rights Society NY

The 2016 edit, digitized from other open reels by Mits Kataoka and Dyke Redmond, features different highlights from the event using both footage from both the Kubota tapes and Kataoka’s LA documentation. It concludes with interviews of participants and their reactions to the event and the media. Two students express their hopeful skepticism for visual telecommunications outside corporate use, noting its potential to facilitate communication between different cultures or people with no previous relationships. However, they also recognize its constraints when dealing with large groups of people. Shortly after the first picturephone event, Paik joined UCLA as a visiting artist, and another call was co-organized by the UCLA Department of Design and Dickson Video Lab with the Long Beach Museum of Art on March 9, 1979. A 30-minute, two-channel video installation of the performance documentation was edited by John Jebb and exhibited at the LBMA from March 25 to May 6, 1979.6 The LA documentation is now part of the Long Beach Museum of Art Video Archive at The Getty Research Institute. Documentation from the New York contingent has not yet been located.6 There was still some difficulty in receiving the video signal from New York in the second iteration of the Video Phone due to a relay problem in Chicago. The artists further experimented with the new video phone features that allowed that facilitation of different formats of communication and connection. Joan Logue, a pioneer of video portraiture, invested in creating “30-second spots” ads for artists on public television. She experimented with two-way, one-minute video portraits in collaboration with Long Beach curator Nancy Drew, using a slow-scan transmitter to print and hard copy images between each location. These experiments anticipated the way that video would reshape communication through screenshots and screen sharing.

Frequently, it is artists who provide these key insights about emerging media. Artists have also been incredibly adept at identifying alternative uses for technologies considered unsalable. In the case of the Video Phone, artists were able to see that the widespread adoption of video communication would be a social phenomenon, even after corporate culture had all but abandoned the technology. They were cognizant that the institutionalization and commercialization of video communication could drastically alter our interactions in daily life, contributing to the rise of the attention economy and, by extension, a society of control. Peter D’Agostino points out in his reflections about a later 1981 Video Phone event:

“Politically speaking, the burgeoning ‘global village’ would not only be controlled primarily by corporate interests such as practicality and profits, but the potential for surveillance and dictatorial control would be greatly increased. And socially, as the possibilities for communication expand, so do the possibilities for miscommunication and information overload.” 7

Transcontinental exchange and cross-fertilization of ideas through the Video Phone experiments foreground other bi-coastal video communication experiments, demonstrating the various ways artists utilized the technology in public, non-commercial spaces.

The process-based Video Phone events and grassroots video networks created spaces to test how new communication systems could be employed in social contexts rather than purely commercial endeavors. In doing so, they were also able to anticipate second-order effects accompanying the rise of personal video communication in an interconnected society. These effects encompass everything from the proliferation of compact personal devices and self-portraiture to the emergence of new fashion that incorporates video elements. Through thoughtful stewardship, involving digitization efforts and artist interviews, we can now bring to light video communication experiments like the Video Phone, revealing how early video pioneers embraced collaboration and interactivity in this burgeoning medium. Furthermore, preserving and managing time-based media works with collective authorship and fragmented documentation presents an exciting opportunity for collaboration between artist archives, estates, and larger institutions housing related materials. This collaborative effort aims to locate, preserve, and provide access to these invaluable materials, contributing to a deeper understanding of the evolution of video communication and its broader impact on contemporary artists’ practices.

1. Ira Schneider and Beryl Korot, eds, Video Art: An Anthology (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977), 2.

2. After Kubota’s passing in 2015, the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation was established by friend and artist Norman Ballard at the artist’s bequest. Reid Ballard serves as the foundation’s Director of Collections and Exhibitions, and Norman Ballard as Executive Director respectively.

3. Bill Seery, Conversation with the author, June 8, 2023.

4. This next iteration of the Video Phone on March 9, 1979 lasted three hours and included artists Paik, Shirley Clarke, Sally Shapiro, Peter Ivers, Nancy Drew, Eric Johnsen, Mrs. Robbins, Gary Lloyd and his dog Renegade, Kataoka and his students from LA. The New York contingent coordinated by Kubota included Logue, Howard, Robbins, Wendy Clarke, Debora Jelin, and William Wegman and his dog Man Ray.

5. Kathy Rae Huffman, “Chronology of Film and Video Exhibitions at the Long Beach Museum of Art, 1974-1999,” The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2006, M.7, 29, http://archives.getty.edu:30008/getty_images/digitalresources/2006m7_lbma/2006m7_lbma_exhibitionchron.pdf

6. Mitsuru Kataoka, Shigeko Kubota, and Nam June Paik, “Picturephone performance / Nam June Paik; edited by John Jebb,” The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Special Collections, 2006. M.7. Video documentation from the New York contingent has not yet been located and may no longer be extant. According to Kubota, Barbara London, Peter Campus, and Bill Viola were also invited to participate from New York but were either not available or declined.

7. Peter D’Agostino, “For a Video/Phone”, Video 80/1, (Spring 1981): 35,

https://sites.temple.edu/csarts/files/2020/04/pdA-For-a-Video-Phone-1981-5p.pdf

Main image

Mits Kataoka and Nam June Paik ed. Mits Kataoka and Dyke Redmond,

Two-Way Video, LA-NYC, Video Event at the AT&T Corporate Offices,

Los Angeles and New York City on January 19, 1979.

Color video with sound,13 min. 42 sec.

Courtesy of Dickson Art Center Video Laboratory and Estate of Mitsuru Kataoka.

Image Description

A screenshot of a color video showing a young man and a woman sitting behind a table. The woman is to the left of the frame. She wears a pink shirt and a pink hat and has long wavy hair. She is holding a small dog in her right arm, and with her left hand places black shaded glasses on top of the dog’s snout. The man, to the right, wears dark clothing and has black hair, and is sitting behind a TV monitor placed on top of the table. He leans over the monitor and holds a long reflective object in his left hand. There are other objects on the table, such as a yellow plastic cup and a voice recorder. In the background, more people sitting on chairs can be seen.