“It Rains in My Heart, It Rains on My Video Art”

Rediscovering Shigeko Kubota’s Broken Diary

"It is about time that I made sense out of nonsense, order out of chaos. Therefore I will spend one or two years of my life on editing the hundreds of hours of videotapes, some of them joyous, some of them painful, some of them public and some of them very private…" – Shigeko Kubota, Audio (Video) Biography in Twelve Chapters (1969-86) A Broken Diary

In 1970, Shigeko Kubota (1937-2015) initiated an extraordinary series of autobiographical single-channel video works—collectively titled Broken Diary—that chronicled her everyday life. These low-tech video journals are intimate and idiosyncratic, at times comic, at times poignant. An eclectic record of personal history and collective memory, the Broken Diary series charts the quotidian details of the artist’s life and, in the process, captures a specific cultural and artistic milieu of the 1970s and 1980s. Conveying a powerful sense of female identity, the Broken Diary journals are among the most resonant but least well-known of Kubota’s works.

Kubota was an innovator who was part of the first, pioneering generation of artists to use video—the Sony Portapak—as a creative tool. (She has stated that her “video life” started when she reviewed the landmark exhibition TV as a Creative Medium at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York for the Japanese art magazine Bijutsu Techo in 1969.)1 She made her first single-channel videotape in 1970 and her first video sculpture, Marcel Duchamp’s Grave, in 1975, and went on to create a distinguished body of video-based sculptural works over the course of her five-decade career. Kubota is perhaps best known for the works in her Duchampiana series (including the 1976 Nude Descending a Staircase) and her video sculptures that integrate elements of the natural world—mountains, water, cherry blossoms—derived from Japanese landscape traditions, such as Three Mountains (1976-79) and River (1979-81). Kubota characterized these works as “video sculptures,” defining a form distinct from “video installations.”

In her original proposal for the Broken Diary project, Kubota outlined a series of twelve autobiographical video “chapters” of various lengths, with a total running time of ninety minutes, to be exhibited as a twelve-channel video installation. “In 1970,” she writes, “I jumped into the creative side and since then, I have recorded the turning points and highlights of my professional and personal life on video. … Hopefully my video diary will help bring out those hidden memories of humankind from the seventies and eighties …”2 Six of the chapters outlined by Kubota, including Europe on ½-Inch a Day (1972), Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky (1973), My Father (1973-75), and SoHo SoAp/Rain Damage (1985) have long been in circulation; the remaining six works have long been considered lost.

The Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation has recently undertaken a major effort to catalogue, conserve, and digitize the roughly 2,000 tapes housed in the artist’s loft after her death in 2015. According to the Foundation, over 800 of the tapes in her archive are on open reel, analogue formats; the vast majority was not intended to function as artworks or for use in video sculptures, but as “personal video chronicles of people and the era.”3

Among the recent discoveries resulting from this extensive, ongoing project are previously unseen materials and footage from Kubota’s video journals, including several of the missing chapters mentioned in the original Broken Diary outline: segments of the Berlin Diary (1970-80), as well as complete versions of the Video Curator Diary (1974-82) and Shigeko in Chicago (1981). (The 1975 Hospital Diary has also recently been identified and is currently being digitized.) In addition to raw footage and completed edits, the archival material includes drawings, paintings, poems, and other relevant documents that relate to the Broken Diary chapters. These newly discovered pieces are revelatory additions to Kubota’s known body of work, further illuminating her contributions to the narratives of video, feminist, and art histories.

The life chronicled in the Broken Diary series reflects the artist’s complex personal history: Kubota was born in 1937 in Niigata, Japan, growing up during wartime in a religious Buddhist family. After establishing herself as a young avant-garde artist and writer in Tokyo, she moved to New York in 1964 at the invitation of Fluxus founder George Maciunas and became thoroughly immersed in the downtown performance art and video scenes. (Maciunas gave her the title of “Vice Chairman of Fluxus.”) Serving as a freelance art journalist for Bijtsu Techo, she was exposed to and participated in events at the heart of the New York experimental art world of the 1960s. In addition to her own artistic practice, in the early 1970s she was part of the art-making collective White, Black, Red and Yellow, with Mary Lucier, Charlotte Warren, and Cecelia Sandoval. From 1974 to 1982 she was the video curator at the pioneering independent cinema Anthology Film Archives, and from 1977 until his death in 2006 she was married to artist Nam June Paik.

Shigeko Kubota, Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky, 1973

Video (black and white, color), 31 minutes, 56 seconds

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

“Video is Victory of Vagina,” Kubota famously declared in her 1968-76 Video Poem, and her earliest diaries chart her solo travels as a woman armed with a Sony Portapak. “I traveled alone with my porta-pak on my back … Porta-pak and I travelled all over Europe, Navajo Land, and Japan without male accompany,” she writes.4 Europe on ½-Inch a Day is a free-spirited romp through Paris, Nice, Brussels, and Amsterdam, with stops at an erotic cabaret and a ritualistic performance art piece, culminating in Kubota’s homage to Marcel Duchamp at his grave in Rouen. In Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky, Kubota’s cross-cultural, color-synthesized document of her month-long stay with a Navajo family in Chinle, Arizona, she focuses on the rhythms of their everyday lives, with an emphasis on the Navajo girls and women.

Several of Kubota’s diaries unflinchingly confront pain and loss. My Father is a profoundly intimate exorcism of grief, with video as a witness to Kubota’s mourning rituals. The artist and her dying father are seen watching television together in Japan on New Year’s Eve, their suffering starkly contrasted with the TV celebrations. After her father’s death, Kubota weeps alone in front of a video monitor. In Trip to Korea, Kubota’s account of Nam June Paik’s return to his native country after a thirty-four-year absence, she documents a reunion with family members and friends, confronting personal and cultural loss and the negation and reclamation of history and memory.

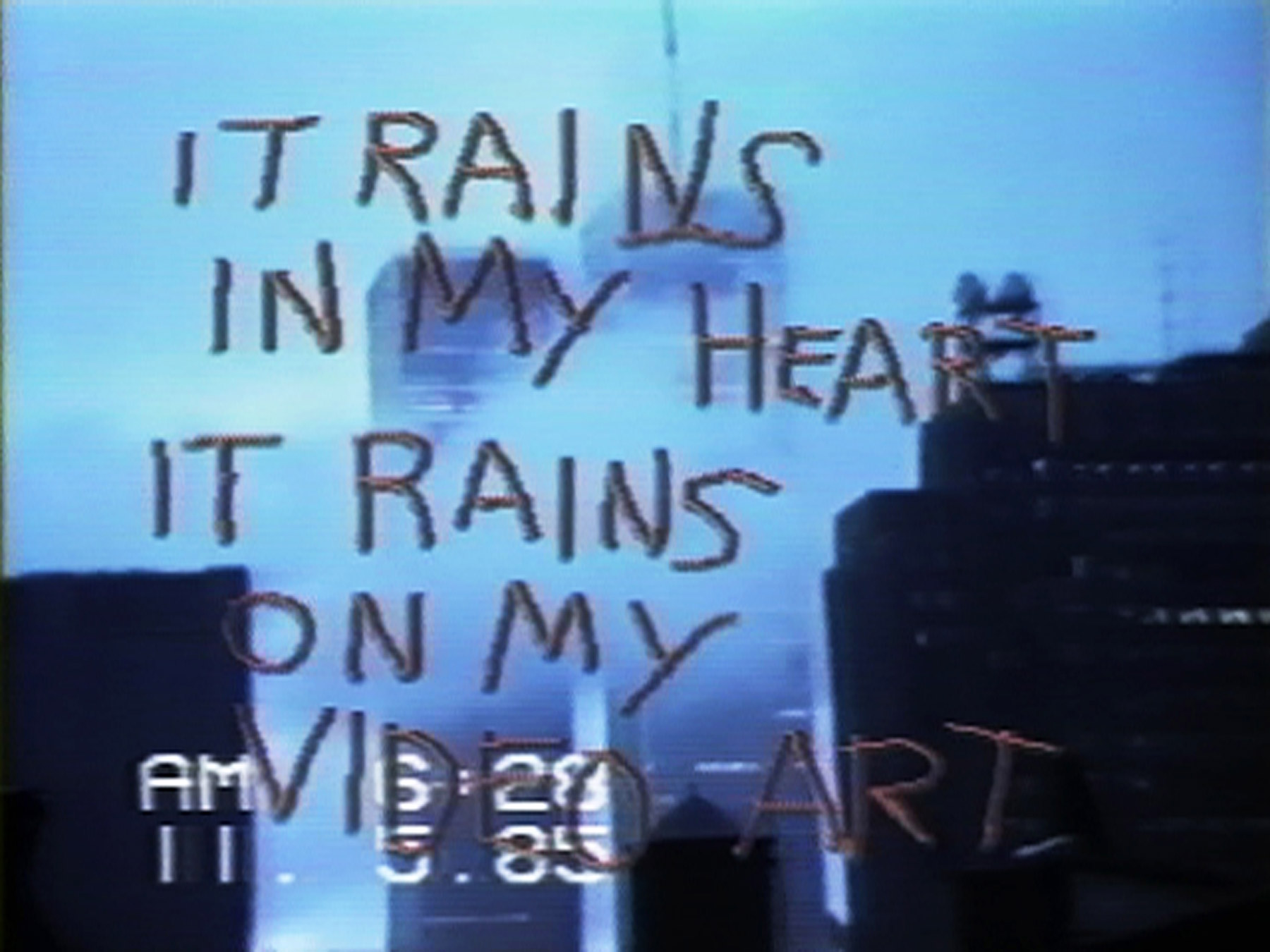

Kubota’s diaries also capture the distinctive physical and cultural landscape of New York’s SoHo in the 1970s and 1980s. In George Maciunas With Two Eyes 1972, George Maciunas With One Eye 1976, Kubota documents the Fluxus founder—a force behind the transformation of SoHo into an artists’ district—as he tours the neighborhood’s cast-iron buildings with artists and friends. SoHo SoAp/Rain Damage is a tragicomic chronicle of a rooftop flood that ravaged Kubota and Paik’s Mercer Street loft studio. Kubota conflates the significance of water in her art with the emotional loss of the artists’ video work and equipment. As she writes over an image of the fog-enshrouded World Trade Center towers, seen from the loft’s rooftop: “It rains in my heart, it rains on my video art … Art imitates nature, nature imitates art.”

Shigeko Kubota, SoHo SoAp/Rain Damage, 1985

Video (color, sound), 8 minutes, 25 seconds

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

The three newly discovered chapters of the Broken Diary add unexpected biographical, emotional, and artistic depth to the series; each brings new insights to our understanding of Kubota as a woman and as an artist in the 1970s and 1980s.

Created on the eve of her departure for Berlin for a Deutsche Akademische Austauschdienst residency in 1980, the Berlin Diary is a raw, wrenching document of personal pain. A static black-and-white camera frames a view of an open loft space; Kubota enters and pulls a chair up to the camera. Her face partially obscured by a vase of flowers, she reads, haltingly, from a sheaf of papers. “I bought an airplane ticket and two suitcases for my trip to Berlin, my trip to death. I may not come back.” The text is poetic, elliptical, and harrowingly confessional: She speaks of sex, her body (“Look at my body—so many scars”), her miscarriages, and death, before breaking into a melancholy rendition of “You Are My Sunshine.”

Shigeko Kubota, Berlin Diary, 1979

Video (black and white, sound), 14 minutes, 01 second segment

Courtesy Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

Autobiography is interwoven with reflection in passages that veer from the concrete to the abstract, and that ultimately point to her art. An allusion to Kubota’s childhood flower garden in Niigata, Japan, leads to a reference to creating reality and truth with video colorizers and synthesizers, “making blue, red, rainbows, twelve tones from white to grey to darker grey to charcoal grey to completely black.”

At one point in the recitation, Kubota refers to her text as a kind of self-analysis: “This is my self-development, using my self, my spirit—I can analyze myself … I am reflecting myself, self-reflection, analyzing yourself by yourself from a different angle.” Here Kubota is self-consciously referencing the psychological feedback enabled by the immediacy and intimacy of the “video mirror.” Although this passage recalls the self-reflexive, conceptual monologues of early video artists such as Vito Acconci, Kubota immediately returns to the deeply personal: “I may die soon, I have a feeling. I have no children. My mother is too old, too far away … Nam June is too far, too …” The segment ends with Kubota singing a slow, haunting song in Japanese.

A second recovered segment of the Berlin Diary finds Kubota standing in front of the broken, abandoned former Japanese embassy in Berlin, musing that during the war she was “hiding from the bombs … My memory about war, I was hungry, starving, starving, starving. This is a scar, this is history.”

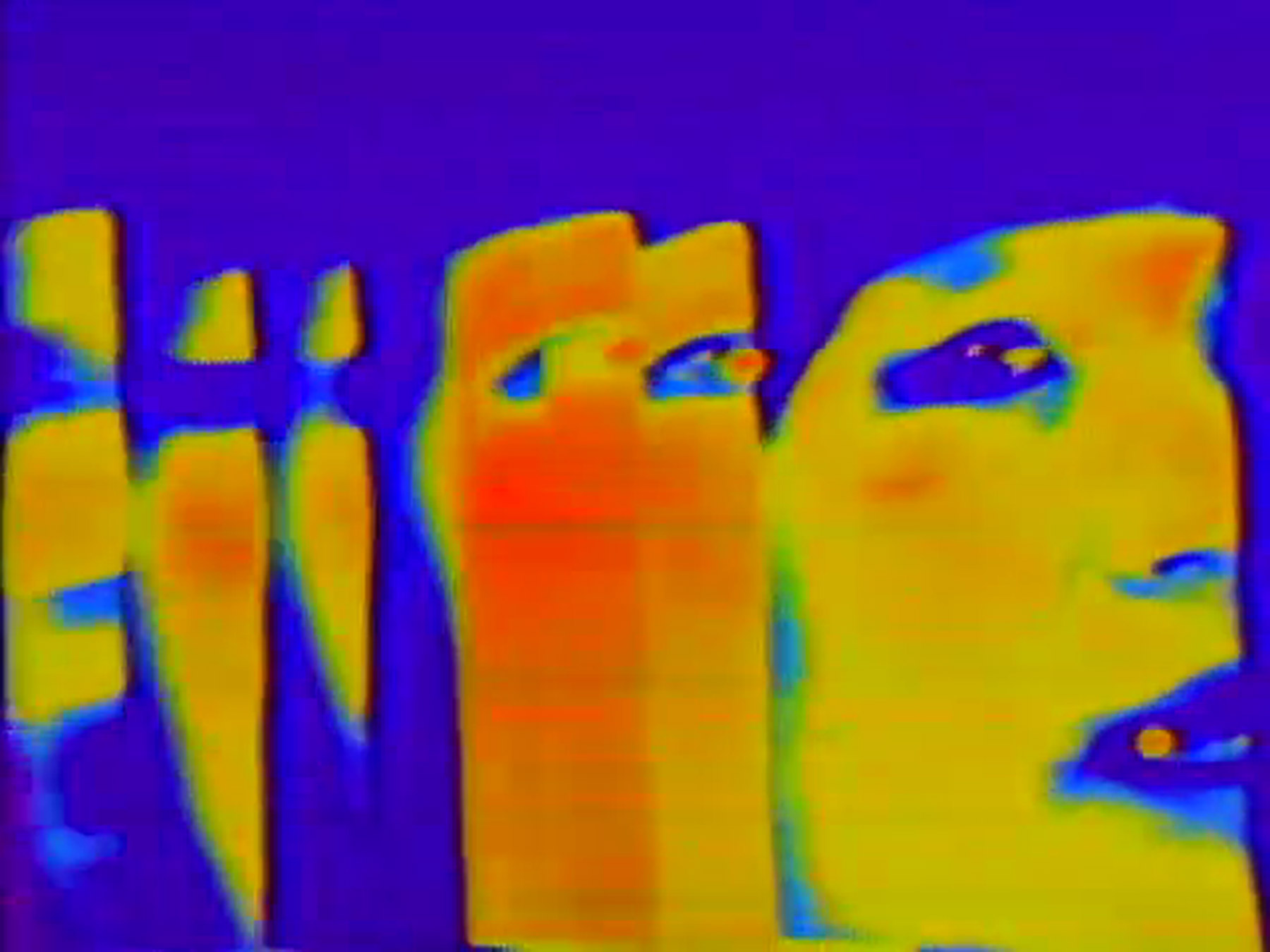

In contrast, the newly recovered Shigeko in Chicago is the opposite in tone, capturing a buoyant, at times mischievous Kubota in vibrant color. The Chicago journal begins where the Berlin Diary leaves off, with Kubota alone, singing. But whereas the black-and-white Berlin Diary ends with a mournful lament, the Chicago chapter opens on a close-up of Kubota rendered in vivid, electronically synthesized patterns, singing in Japanese and chanting, “Nam June, Nam June …” The sequence cuts on her laughter.

Shigeko Kubota, Shigeko in Chicago, 1981

Video (color, sound), 14 minutes

Courtesy Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

Created while Kubota was artist-in-residence at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Shigeko in Chicago takes the form of a free-associative video collage: informal people-on-the street interviews are mixed with close-up portraits of women discussing their lives, while Kubota subjects their images to live electronic colorizing. Elliptical vignettes—Kubota violently pours coffee into a tray of oversized cups and saucers; a dangling wine opener suggests a hanging figure—are juxtaposed with references to menstrual blood and musings on illicit drugs. Markers of the 1980s (such as Ray Ban sunglasses) and scenes of Kubota along the Chicago lakefront locate the piece in a specific time and place. Like the Berlin segments, the newly recovered Chicago diary yields yet another facet of the artist, an episodic portrait unfolding with each chapter.

The third newly discovered journal, Video Curator Diary, holds additional surprises: The piece documents a cable TV Video Art Telethon fundraiser for the video program of Anthology Film Archives, complete with a host, artist Maxi Cohen, and Kubota as a glamorous, loquacious pitch-person for video art. Guests, including video artists Ed Emshwiller, Edin Velez, and Joan Logue, offer on-air testimonials. The piece is a charmingly low-tech, candid glimpse of the collective passion, shared ethos, and camaraderie of the nascent New York video art community in the early 1980s.

Shigeko Kubota, Video Curator Diary, 1974

Video (color, sound), 11 minutes, 22 seconds

Courtesy Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

With its autobiographical focus on the intimate details of a woman’s personal and professional life, Kubota’s Broken Diary project is distinctive in early video art. In an age of obsessive self-documentation, when the minutiae of daily life are routinely recorded and publicly shared on social media, it may be difficult to appreciate the rarity of similar self-revelatory impulses in early video art. Despite its purported “narcissistic” tendencies and emphasis on the artist performing for the camera, early video art typically privileged the formal, metaphorical, and conceptual over the autobiographical and diaristic.5 (By contrast, the personal diary features prominently in experimental filmmaking of that era; the late Jonas Mekas’s epic film diary project is among the most important examples.) Kubota herself characterized these chronicles as a form of writing, stating in the Berlin Diary, “I will make this video diary as a writer does,” further distinguishing this body of work from her video sculptures.

Kubota’s video journals not only shed new light on the woman and the artist behind (and in front of) the camera, they also open a window onto the collective cultural past of a burgeoning artistic community, revealing, as Kubota suggested, the “hidden memories … from the seventies and eighties.”

“This endeavor will also serve, hopefully, as a model for other video makers … who are hoarding thousands of hours of undigested video plastic memories and are afraid to look back,”6 writes Kubota, speaking as much to her future archivists as to her peers in the 1980s. The Broken Diary project—and the ongoing rediscovery and restoration of these revelatory, previously unseen chapters—reminds us of the power of personal history to illuminate our collective cultural history. As Kubota concludes, “Indeed, this is the first time in our history that so much collective memory has been recorded. Jung and Freud must rewrite their theories in this video century.”7

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Norman Ballard and Reid Ballard of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation for their generosity in making the newly discovered Broken Diary chapters available to me for viewing, and for sharing their unfolding research on this ongoing preservation project.

1 Shigeko Kubota, Audio (Video) Biography in Twelve Chapters (1969-86) A Broken Diary, (proposal), Electronic Arts Intermix Archives, New York, (n.d.).

2 Ibid.

3 Norman Ballard, Director of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation, in an email to the author, January 30, 2019.

4 Shigeko Kubota, Video Poem, 1968-76

5 This is not to suggest that autobiographical and diaristic strategies were entirely absent from early video art. For example, Juan Downey’s body of video works from the 1970s weaves personal history and a search for identity into broader investigations of cultural and social structures; Vito Acconci incorporated autobiographical details into his psychodramatic monologues of the same decade. Artists as diverse as Shirley Clarke (The Tee Pee Video Space Troupe: The First Years, 1970-71), Ant Farm (Ant Farm’s Dirty Dishes, 1971), and Raindance (The Rays, 1970) used the Portapak to informally document their everyday lives and environments. Kubota’s Broken Diary series is distinctive in that, in addition to emphasizing the artist’s experiences as a woman, it was conceived as a deliberate, continuous project of chronicling her personal life on video over an extended period, starting in the earliest years of the medium. The “video diary” as a recognized genre proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s. George Kuchar, among the most prolific video diarists, began his legendary video journals in the mid-1980s.

6 Shigeko Kubota, Audio (Video) Biography in Twelve Chapters (1969-86) A Broken Diary

Main image

Shigeko Kubota, Shigeko in Chicago, 1981

Video (color, with sound), 14 minutes

Courtesy Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation