Made in Los Angeles

Los Angeles artists Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, and John McCracken are known for using innovative materials and complex technical processes, developed in the context of an emerging art scene in the 1960s. On the occasion of the publication of her book Made in Los Angeles: Materials, Processes, and the Birth of West Coast Minimalism (Getty Conservation Institute, 2016), conservation scientist Rachel Rivenc spoke with art historian Lucy Bradnock about the place of craftsmanship, the conceptual meaning of materials, and the ethics of conserving aging artworks.

Lucy Bradnock: You write that your project, like the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative from which it emerged, was compelled by a sense of urgency.1 What drove that sense?

Rachel Rivenc: One of the greatest strengths of the PST initiative was the organic way it grew out of existing research; it was a very content-driven initiative. The Getty Research Institute had been conducting oral histories with artists and other important participants of the post-war L.A. art scene for years. I think at some point there was a realization that it was important to capture all the information and vernacular knowledge held by those who witnessed first hand the growth of LA as an art capital while they were still around. Shortly after I became involved in the project, Craig Kauffman and John McCracken passed away – the loss of these two artists was not only very sad, it felt like a wake up-call. The information really had to be recorded while it was still possible.

Bradnock: What was the state of knowledge about the materials and processes in these works when you and the GCI team embarked on your research?

Rivenc: Well, there are several layers to your question. Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s made use of new and industrial materials, especially plastics, in a pioneering way. Their engagement with these materials was in many ways very distinctive and had a profound impact. Conservation reacts to what artists do and so the evolution of the field in some ways mirrors the evolution of art – sometimes with a delay. Two or three decades ago, only a tiny handful of far-sighted people were doing research into the conservation of plastics. In the past few years, research projects have multiplied and interest in this issue has become massive: conservators are eager to have more information on deterioration mechanisms, solutions for prevention, and effect of treatments for synthetic materials. In regard to L.A. art specifically, I think everybody, including the artists themselves but also critics and art historians, were very aware of the importance of materials and processes and what they permitted the artists to achieve. However, the topic had not been studied systematically and there were a lot of misconceptions going around.

Bradnock: Do the kinds of material experiments and innovation that you describe as a feature of this group of artists present an archival challenge?

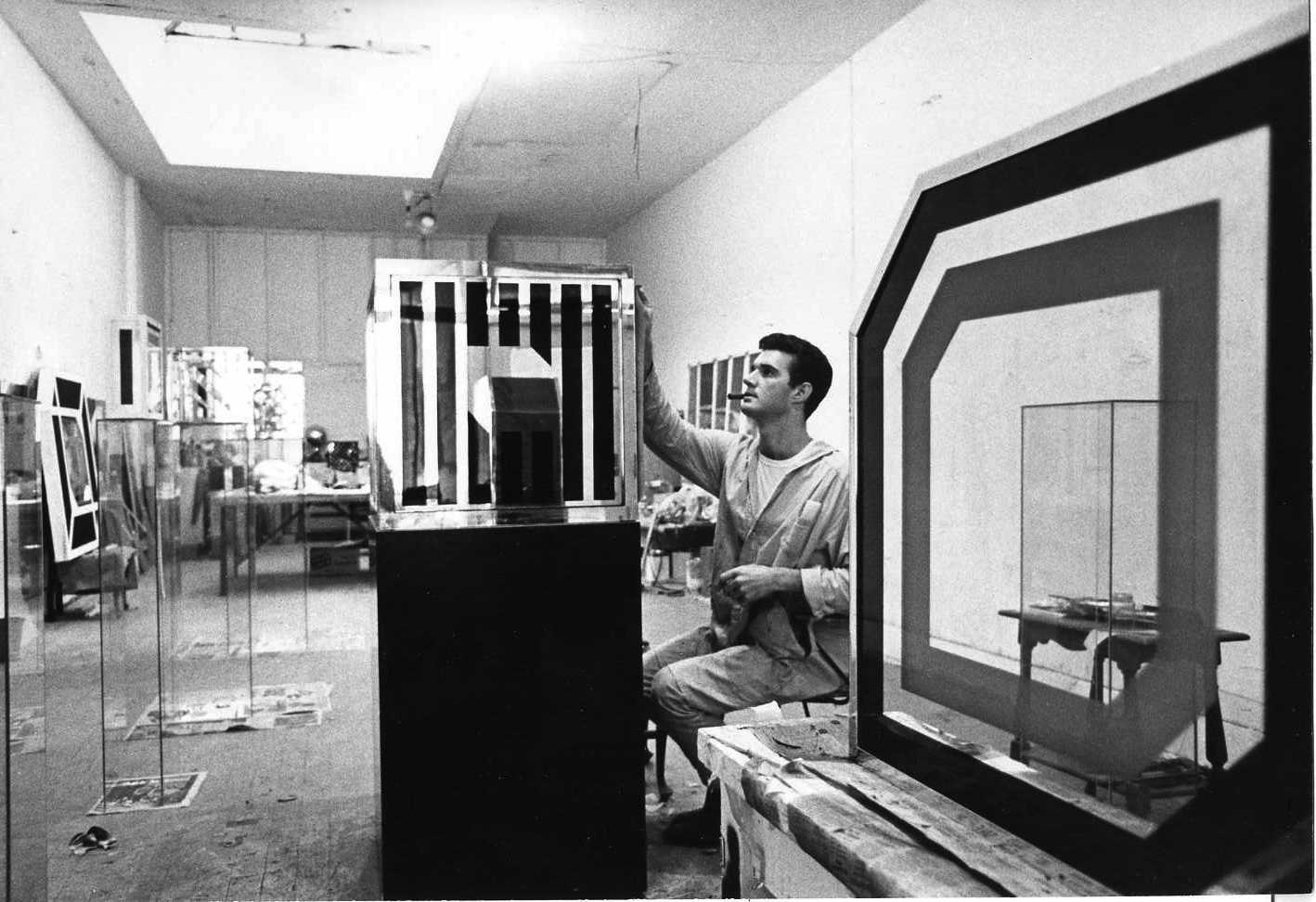

Rivenc: I think the first challenge was to realize that I had to drastically narrow the focus of my study if I wanted to go into any kind of depth – hence the choice of four artists: Larry Bell, Craig Kauffman, John McCracken and Bob Irwin. It was a tough choice because so many other artists also did amazing experiments with materials but in the end I chose these four because of the significance of their artistic contribution and their pioneering use of materials. I also wanted my research to cover a range of different materials and techniques. With Bell using vacuum coating of glass, Kauffman vacuum forming of plastics, McCracken poured polyester, and Irwin a variety of industrial paints and plastics, the book covers a wide range of materials and their uses.

My starting point, and a key tool throughout, was oral history. I did many interviews with the artists themselves when possible but also with anybody who might have witnessed their studio practice. It’s important to cross-reference interviews – we’re talking about information that dates back fifty years now, so everybody’s memory is often incomplete at this point, or locked in a narrative, anecdotes that have been repeated many times over. I found that multiple interviews were especially useful to go beyond the narrative that artists might have constructed over the years. Most of these artists did not keep detailed records of their studio activity (or if they did I have not found it!) but other documents are useful: photographs, drawings and sketches, suppliers’ order sheets, even old film footage in the case of Bell. In the end, though, I always went back to the works themselves; so much can be learned from simple visual examination. Even when the artist describes his process in detail, it can remain quite abstract until you look at the object and it all comes together. Chemical analyses can also confirm the composition of a product or give more details. Since commercial products do not always disclose their composition, an artist can think he’s using a certain resin or paint when in fact it turns out to be something else. For example, Kauffman thought he always used acrylic-based paints to paint his vacuum-formed plastic pieces but for some series it turned out to be nitrocellulose.

Bradnock: Oral histories can be both useful and challenging in reconstructing the historical and material record. There are other issues too. Part of the project of PST was to question the prevalent myths of Los Angeles art during that period …

Rivenc: Yes there is definitely a certain amount of wrestling with the mythologizing by the participants of the period but also with what you call the prevalent myths of L.A. art. A part of my study was to examine and often nuance the ideas that L.A. art in the 1960s and ’70s was tied to both the aerospace industry and to typically Californian subcultures such as surfing and car customizing and that all California artists engaged in these activities, which was not the case.

Bradnock: What is the significance of craft as opposed to industrial manufacture?

Rivenc: This is a point that is really crucial to understanding L.A. art of that period. Although Kauffman in particular was interested at some point in mass production, the idea of high-quality craftsmanship is at the heart of the relationship these four artists had with the production process. A few scholars, including you, have highlighted the paradox between the cool, nonexpressive surfaces that appear as though they were industrially produced, on one hand, and the intensive labor and high level of skills necessary to achieve these surfaces, on the other hand. When you examine these objects up close, you realize fairly quickly that although incredibly well made, they are not completely perfect, or devoid of accidents. To me those imperfections are precious because they say something about the work’s maker and make each piece unique. Also, the processes are too complex for mass production; they clearly include a great deal of sensitivity and intuition. Once, Bell was asked if he could remake a piece he had done in the 1970s. His response was that he could make a new piece but by no means could he approximate the first one in part because he had at the time a completely different set of skills and experience, but also because a lot of the features he loved in the piece were accidents. All of these artists valued craftsmanship tremendously. Irwin, for example, cites Raku earthenware as a source of inspiration for his relationship to craft, his insistence on everything being perfect, even the parts that are unseen. On the other hand, Irwin was the only one of the four who embraced delegating work to fabricators fully, because he realized early on that he did not want to be limited to one type of skill and could not achieve excellence in all the media he wanted to explore. I think for Kauffman, Bell and McCracken, being the maker remained very important, even if at times they thought it was mostly a practical decision. McCracken has talked about how the energy of a piece would be different if he did not make it; Bell has described how he fell in love with his complicated vacuum forming process and loved to wrestle with it, as unforgiving as it sometimes was. It’s also about control, of course.

John McCracken, Installation view of the 2010 group exhibition Primary Atmospheres: Works from California 1960-1970 at David Zwirner, New York

© The Estate of John McCracken

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Bradnock: Is it also about a kind of material commitment, both on Bell’s part and also on yours in that you pursue close material analysis as a means to access the philosophical and perceptual meaning of these works?

Rivenc: Bell himself has pointed out that there is an element of absurdity, of excessiveness in his process, in its complication, in the time and learning commitment it represented. It’s incredibly finicky. To me when you know this it gives an added dimension to the works. With my research I went into a great level of detail to understand as exactly as possible how the works were made. There were several reasons for this: one is to build up knowledge for technical art history. We go to great lengths to attempt to reconstitute how painters centuries ago painted their pictures but with these works we can save ourselves a lot of trouble by documenting these processes while the artists are still alive and the techniques still in use. Hopefully this information will be useful at some point to conservators trying to come up with treatment strategies. But you are right; the part that interests me the most is how this information enhances our understanding of a work of art. I think beyond its immediate goal of preserving objects for the future, conservation can teach us a lot about materiality – what it means to be a physical object. A physical object is far more than an image – it has a tactility, a sensuality, it has a whole set of ideological, sociological, and historical values embedded in its physicality. Sometimes this approach might complicate the question as to what discipline exactly you are operating in: is it conservation, conservation science, art history, or technical art history? To me it doesn’t really matter. Looking at the objects and learning about them from as many different angles as possible is what enriches our understanding of the works.

Bradnock: How do you as a historian but also a scientist navigate the ethical implications of conserving works that prioritised pristine finishes and the effects of perfect surfaces?

Rivenc: I am definitely hoping that my study will have implications for the conservation of these objects – not in terms of specific directions as to “how to repair this or that” but more in terms of rethinking these artists’ relationships to materials and processes, which I think is a very important criteria when deciding conservation interventions. These works are for the most part fairly stable, if handled with care and stored properly, but one of the main conservation challenges stems from the necessity to keep these works looking pristine for them to function aesthetically as intended by their creators.

Bradnock: So should the aim be to preserve the historic materials or a contemporary visual experience?

Rivenc: A lot of the work is about perceptual effects that depend on the reflectivity or translucence of the surfaces, so any damage is eminently distracting. This has tended to lead the custodians of the works to use any means necessary to reinstate their aesthetic functionality, which often means very invasive repairs: re-sanding, re-painting, in some extreme cases re-fabricating. Extensive interventions take place at the expense of original materials, and when original materials are lost we lose information about the historical and technological context. When we erase all signs of aging and make these works look new, we blur the boundaries between the time of creation and restoration, and negate the historical character of the works. This is done for different reasons, be it at the insistence of the artists themselves, who are interested in keeping the work alive and relevant, rather than as historical documents, or as a result of market forces. Even this is changing now: in recent years, perhaps as a result of the increased institutional recognition of this group of artists, there is more appreciation for light signs of aging, for a mild patina that suggests period authenticity. Deciding not to intervene extensively also retains a sense of the artists’ engagement with the object. This engagement, I discovered during my research, was profound and pivotal: the decision not to delegate the fabrication was not solely practical. I don’t have an answer on what conservators should do exactly, but I do advocate that a thorough understanding of all material aspects of the works should be part of an informed decision. It’s a complex issue. In this instance we operate at the junction of historicity and contemporaneity and we have the difficult task of drawing the line.

Bradnock: I’m intrigued by the different kinds of looking that these investigations entail – in the close scientific investigation of the works, is it still possible to be seduced by them?

Rivenc: Yes, I think it is possible. There are different kinds of seductions. Whether it is an in-depth visual examination or chemical analyses, there is something very exciting about the feeling of discovery, of uncovering something that was hidden. It is a little bit like a detective investigation, or assembling the different pieces of a puzzle. Of course it has to be a back and forth between scales, micro and macro – you have to remember to look up once in a while, and be enchanted by the work again.

1Pacific Standard Time began in 2002 as a Getty initiative to recover the historical record of art, architecture, and visual culture in Southern California between 1945 and 1980, and grew into a region-wide collaboration among more than sixty cultural institutions, culminating in a series of exhibitions and events from October 2011 to April 2012 across Southern California. The initiative resulted in more than forty publications documenting Los Angeles’ impact on art history during the post-war years. See http://www.pacificstandardtime.org/.

Further Reading

Larry Bell and Marianne Stockebrand, “Larry Bell in Conversation with Marianne Stockebrand,” Chinati Foundation Newsletter vol. 20 (Marfa: Chinati Foundation, 2015).

Robin Clark, ed. Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

Robin Clark, John McCracken: Works from 1963-2011 (New York and Santa Fe: David Zwirner and Radius Books, 2014).

Tom Learner, Emma Richardson and Rachel Rivenc. From Start to Finish: De Wain Valentine’s Gray Column (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2011).

Rebecca Peabody et al. Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles Art, 1945-1980 (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011).

Rachel Rivenc, Made in Los Angeles: Materials, Processes, and the Birth of West Coast Minimalism (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2016).