For Art to Flourish and Leave its Trace

When Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus School, proposed a new unity between art and technology in 1923, it stimulated spirited debate about the changing forms of art and design. And yet, over time artists have embraced a steady succession of technological innovations as creative mediums, ranging from photography and film to video, software, and the web. When Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel Corporation, anticipated the breakneck acceleration in computing power in 1965—commonly known as Moore’s Law—it was the rate of change that his prediction stressed. Keeping up with both the nature and the rate of change is a ubiquitous 21st century effort, especially in the arts and museums.

Art museums pledge to collect, display, study, interpret, and conserve works of art because they provide rich and soulful echoes of who we are. This promise, made to our public today and our public ten, 50, and 100 years from now, has relied on some interlude of time between art creation and its interpretation that allowed for the construction of scaffolds upon which meaning-making dependably rests. With the compression of this precious temporal interlude, how will art made using interactive, decidedly variable, hastily obsolescent high-tech media fare? Digital and computer-based artworks in museum collections are an active force behind retooling the contemporary art museum and expanding methods of stewardship.

Pip Laurenson has devoted her career to these questions and she is also one of the principal architects of an international conference Media in Transition at Tate on November 18, 19, and 20, 2015, a gathering that is co-hosted by the Getty Conservation Institute and the Getty Research Institute. The explicit goal behind Media In Transition is to explore new approaches and fresh ways of thinking about the most burning challenges underlying the stewardship and conservation of time-based media works of art today. In preparation for the conference, The New Art Trust and Pamela and Richard Kramlich, vanguard collectors of media art, invited the speakers to assemble for two days to surface and identify cross currents and connections between the specific case studies and the larger themes of the conference. While together, I sat down with Pip to discuss her views on some of the big issues facing media art collections.

Jill Sterrett: Pip, why is keeping media art tricky for museums?

Pip Laurenson: My answer comes in three parts. First, time-based media artworks raise questions for the museum about being a proficient place for the works created in 21st century mediums—art forms that range from multi-part physical installations to bytes and performances. Second, it is about learning much more about how to preserve the experience of a work of art, not just its physical parts. Finally, it’s about leveraging the museum as a place for artists not only to do things in the world but also as a place where they can have an active role in the future lives of the things they have put out into the world.

A number of years ago I met with Ceal Floyer at Tate’s Collection Center to talk about her work Carousel from 1996. Carousel is made from a record player that plays a vinyl record upon which is recorded the sound of a carousel slide projector. During this conversation a fairly standard dialog about the future life of this work took a fascinating twist and turned into an exploration about what it might look like for the museum to work closely with Ceal while she created the future form that Carousel might take.

Working with artists, such as Ceal, is one of the reasons that a career spent in close contact with a museum collection is such a joy. I believe in what museums do to honor history and what they do to preserve and enable evidence of that historical past to continue through art’s material forms. So the pivotal matter is how to allow the artwork to unfold and change—to be open to dynamic relationships with artists around the evolution and legacy of their work—and be mindful of our responsibility to their histories.

Sterrett: So this business of objects is about people, and very centrally about the artists who make them. Is it possible to collect an artist’s practice along with the artwork?

Laurenson: This is one of the next big hurdles, to honor the work in a way that also makes room for what we learn while the artist works with us. It does point to the nature of an artist’s relationship with a museum. How artworks are co-produced, co-curated, and co-conserved is an important theme reflecting changing social values. Some works may have to adapt because of changing technologies or maybe they were dependent on something that no longer exists. Take, for example, Tania Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #5 from 2008. This work is one of the live works in Tate’s Collection and has as one of its conditions of performance that it must be performed using genuine mounted policeman and horses who are trained and work to control crowds. Bruguera tests and leverages the relationships between the museum and its local police force with every attempt to perform this work. One of the ongoing conversations is how this work might be adapted in the future to be able to continue to have the same conceptual meaning in a new social situation when horses are no longer used in crowd control. How are museums incorporating a thoughtful place for the artists represented in their collections for the simple reason that they have a stake in the legacy of their own work? Thinking with them about the future presentations of the work makes the museum responsive to the various reasons why things change; shifts that range from the architectural, cultural, contextual to the technological? How does the artwork retain the essential trace of itself in this negotiation? This kind of thinking requires a shift from the traditional mindset and training in conservation. It also augments the idea that the museum is home to objects by suggesting the museum is also home to evolving social values.

Sterrett: I hear you saying that the museum is home to material objects and to a whole set of experiences that live in the real world as well. Let’s talk about preserving ‘experiences’. Whose experiences are we keeping?

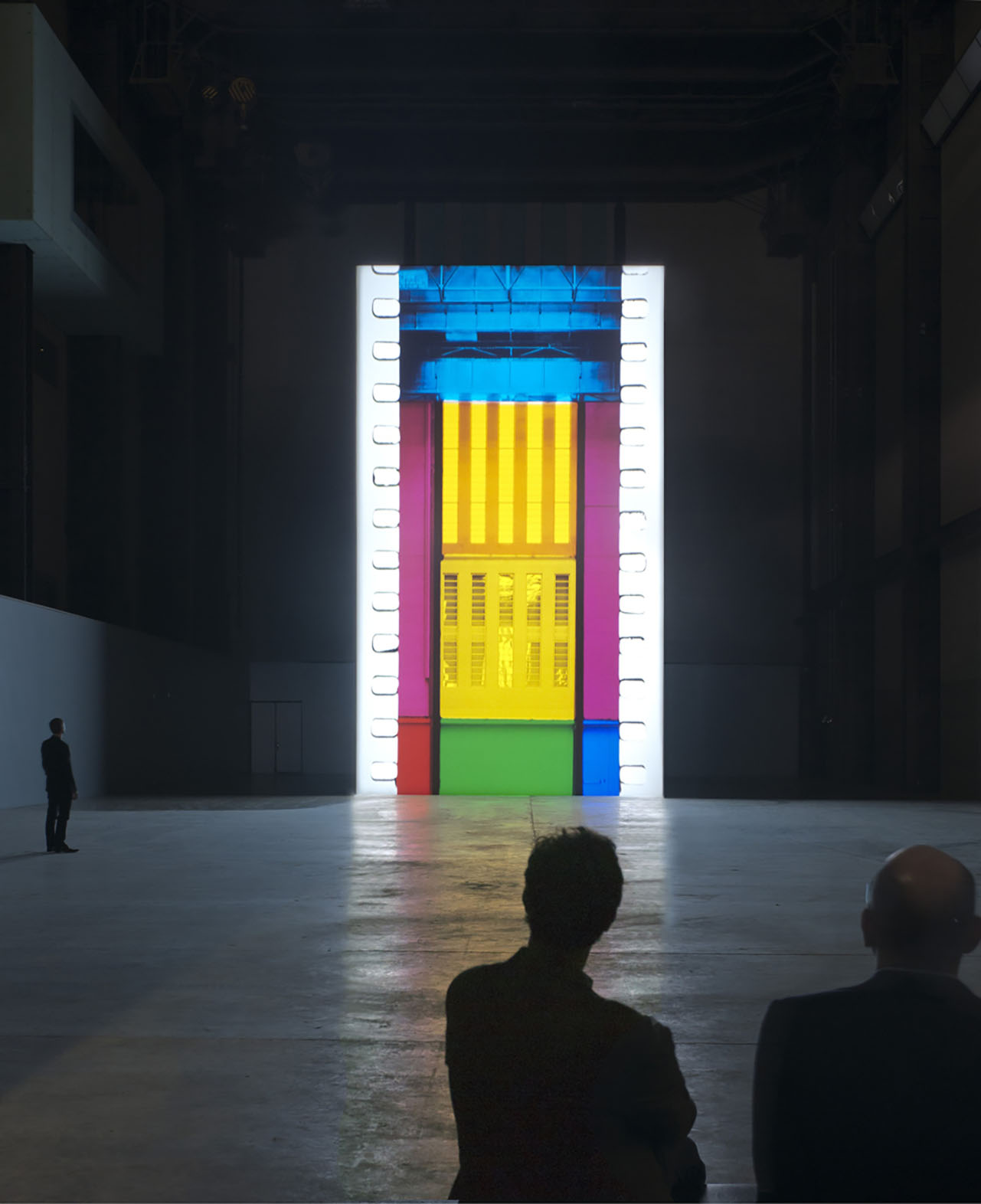

Laurenson: Reconstructing experience invites us to consider and take stock of an array of contingent features. What are those things? It is the classic conservation thought experiment to imagine the visitor experience in 30 years. Imagine a 2041 encounter with Tacita Dean’s installation, FILM, which she created for the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in 2011. Standard museum practice attempts to hold the object in stasis by managing the environment, light, and other variables that make material things deteriorate. With FILM there’s the experience of film, the creation of a moment of black by the shutter between frames, the quality of the color and image as light passes through the emulsion, and then there is the Turbine Hall. Working with the philosopher Barry Smith of the Center for the Senses in London, at Media in Transition we are aiming to draw on expertise developed in different domains that alerts us to the fact that so much of what we experience about these multisensory artworks is subliminal. Discourse that starts and ends purely with a debate about mathematical parameters, such as resolution, will always be inadequate to the decisions we need to make about the future of artworks. Does it matter if visitors in the future even recognize a celluloid movie experience? In some ways this thought experiment aligns with a familiar problem of semantic drift that comes with the passing of time, but in other ways it is very different because media artworks can be removed from their artistic media. Unlike paint and canvas, with media works it is the construction of meaning and value that maintains the relationship between the media and the work and holds these things together, rather than physics and chemistry. For some artists, some forms of artistic practice, and for some artworks, the aesthetic impact of these shifts will not be important, whereas for others they will be devastating. The impact of these changes on these works is a subject wide open for discovery and a rich thinking ground for both neuroscience and philosophy.

Sterrett: On this challenge of preserving experience, is there inspiration and direction to be derived from allied disciplines?

Laurenson: I’ve enjoyed being part of a cross-disciplinary group that brings archivists, record keepers, curators, conservators, and philosophers together to think about the lives of digital things. This group is convened as part of the Pericles Project, a project that is all about ensuring that digital content remains accessible in an environment that is subject to continual change.

A perspective stemming from the record keepers has grabbed my attention. In this community, everything is a record and every record has an active life. In fact, the objection the record keeping community has with traditional preservation is this very notion that a record’s active life is not embraced as an act of long-term stewardship. Only when a record moves from its active life to the archive do the tenets of preservation kick in. What if the lines of preservation were redrawn to include the moments of creation and its ensuing life?

Sterrett: Contemporary art conservation embraces an artwork’s active life. Might that be one of the headlines and one of the underlying provocations of the Media in Transition conference?

Laurenson: Indeed. If an artwork remains active and there’s a role for preservation then I think figuring out the meaningful but sometimes fuzzy moments of its transitions would be instructive. This lays the groundwork for a different way of understanding the relationship between the artist and conservation as a rich and evolving dialogue. There is also work to be done for us to think about how to conceive of the phase of an artwork’s life after the artist has died, as well as the transition from the contemporary to the historic; thinking that traditional modes of operating will somehow suddenly become appropriate seems problematic to me. Within contemporary art conservation one sometimes hears the occasional weary complaint about how it is all so complicated or how the artist changes her mind, how contradictions exist between an artist’s actions and expressions of intent, or how the artwork does not fit into museum structures and rubrics. Imagine turning this perspective on its head to see the problem as the museum’s rather than the artwork’s? Imagine if we saw this as the museum having failed to allow certain things to happen that enable the artwork to do its job and flourish?

I am absolutely and fundamentally a museum person, which makes balancing a respect for history and enabling an artwork to flourish a fascinating challenge. A colleague Eric Piil, who works as a conservation associate at the Kramlich Collection, drew our attention to a extraordinary term coined by the poet Keats: “Negative Capability.” Negative Capability is the ability to be “in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”1 Thinking about the role of the museum with regards to history and the decisions we make every day in relation to the lives of contemporary artworks feels like something that might call out for Negative Capability. As always we might learn from some of the artists involved in the [Media in Transition] conference as to how to enact this capacity more robustly and more elegantly.

1 John Keats to George and Tom Keats, 21 December 1817, in The Complete Poetical Works and Letters of John Keats (Cambridge: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1899), 277.

The views expressed in this interview reflect the personal opinions of Pip Laurenson. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions, views, thoughts and positions of Tate.