Donald Judd Writings

There’s Nothing Minimal About This Book

Robin Clark: Flavin and Caitlin, congratulations on the recent release of Donald Judd Writings. Before we discuss the genesis of the new book, would you share some background about Judd Foundation?

Caitlin Murray: The mission of Judd Foundation is to maintain and preserve Donald Judd’s permanently installed living and working spaces, libraries, and archives in both New York and Marfa. This includes providing access to not only these spaces and resources, but also developing scholarly and educational programs, including exhibitions and publications. In Judd’s own words, “The purpose of the foundation is to preserve my work and that of others and to preserve this work in spaces I consider appropriate for it.” He continues, “The installations in New York and Marfa are a standard for the installation of my work elsewhere.”

Clark: What can you tell us about the new volume of Judd’s writings?

Murray: Last year Judd Foundation published Donald Judd Writings, which spans from 1958 to 1993. In addition, we republished Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959-1975. Both of these volumes include essential writings by Judd and cover an incredible array of topics from art and architecture to politics and the environment. There are a variety of reasons for publishing Donald Judd Writings. As separate volumes, neither reflects the totality of Judd’s thinking. Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959-1975, published in his lifetime by The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, focuses primarily on short reviews that Judd wrote as a for-hire art critic. These reviews are reflective of what was happening in art in the early 1960s in New York and display Judd’s developing style as a writer. Also published during his lifetime, Donald Judd Complete Writings 1975-1986 emphasizes the next phase of Judd’s life as an artist who also wrote extensively. Unlike the reviews written on assignment, these essays are on topics of his choosing, including writings on the relationship between art and architecture, his projects in Marfa, and his political positions. Published by the Van Abbemuseum in 1987, this book has been out of print for a long time. In fact, this book is so hard to find that I use a photocopy of the original for reference. So necessity was another reason for a new volume of Judd’s writing. We wanted to make sure that Judd’s writing could reach as wide an audience as possible.

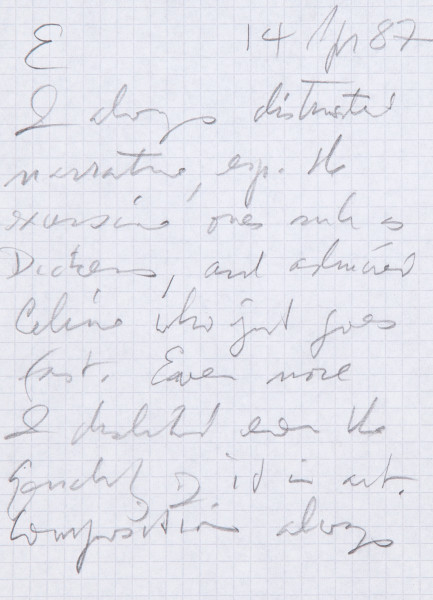

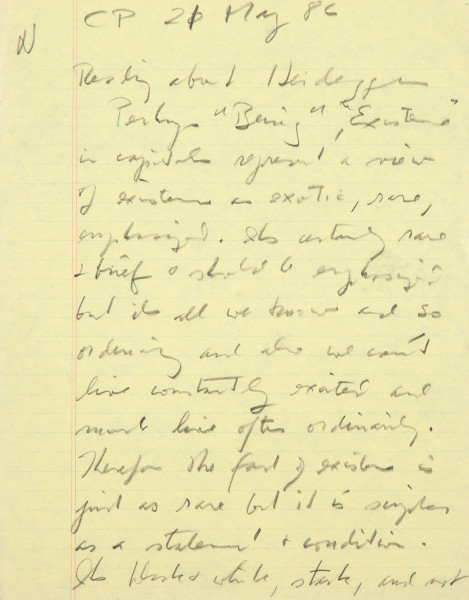

Lastly, I would say that the publication of Donald Judd Writings was essential in that it includes a nearly comprehensive selection of Judd’s writing, from early essays written while Judd was a student at Columbia University to his last essay, “Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in particular,” written in 1993, the year before Judd’s death. Beyond its breadth, this volume also includes hundreds of unpublished notes written by Judd throughout his life, but primarily in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These notes provide insight into Judd’s daily thinking and writing habits and were often the genesis for longer, more developed essays.

Clark: How would you describe the research process?

Murray: This leads us into the archives. If not for the processing of the Donald Judd Archives, this project would have not only been difficult, but the selection of writings would have been quite different. Through the organization of the archives, housed in our office in Marfa, Texas, we were able to see the full span of Judd’s published and unpublished work. The archives contain over 30 document boxes of handwritten and typed drafts of notes and essays. We went through each box, looking at every page to determine if it should be included in the new volume. Flavin made the editorial decision early on that we would include all writings that we could properly transcribe. This largely pertains to the notes, which were all handwritten, and if you have a copy of the book, you can see for yourself the quality of Judd’s script. I typed all of these notes from the original and they were then checked and re-checked by Flavin and myself, as well as by Ellie Meyer, a former assistant of Judd’s and the Foundation’s Catalogue Raisonné Research Manager, who typed many of his essays while working for Judd.

We are lucky to have robust archives documenting a wide range of Judd’s life and work. Beyond Judd’s writings, we have substantial holdings of drawings, fabricator and exhibition records, photographs, exhibition ephemera, and publications. As I mentioned, the Judd Foundation Archives are located in Marfa. We operate by appointment and also work to fulfill off-site research requests, since we know that we are remotely located. We hope that both our publications and the archive itself can be a generative starting place for new scholarship.

Clark: Flavin has commented that “there’s nothing minimal about this book,” and readers may find that although it’s compact, the new volume is something like a universe in a teacup. Is it something you anticipate readers engaging start to finish, or more likely hopping around, like an encyclopedia?

Murray: I think that this book allows for all kinds of reading. I imagine that most readers will not read the book from start to finish, but instead will read based on interest, perhaps focusing on particular artists or topics that they find most fascinating. The chronological structure of the book was definitely the best fit for these writings. Organizing the text into themes would have been too reductive for Judd’s essays, which often cover many different fields of inquiry at one time.

Clark: The book is a dense, compact object with the proportions of a brick. It’s bound in orange cloth with blue endpapers, saturated hues familiar from Judd’s multicolor works. Does the form of the book allude to Judd’s parallel practices as an architect and sculptor? How did the design of the book evolve?

Judd: I wanted it compact and complete: all the writings in one volume so that the spread of time, the change of Don’s thought, and its continuity, would be evident. After that it was a case of working with Mike Dyer to make it as much of a real, tangible object as possible (while keeping the price low) and to get rid of distractions.

Clark: Judd was a collector of many things including his writings, his art, art by others, books, and buildings. Can you describe the way that Judd lived with his collections, and how they may have informed his work?

Murray: Judd as a collector is a lot to address, but in relationship to his writings, I think that the library is a wonderful area to dig into. Judd’s library in Marfa is split into two rooms. One room focuses on books on twentieth-century topics, which Judd arranged by subject matter such as art, architecture, and philosophy. The other room focuses on pre-twentieth-century topics, which Judd arranged by country. These libraries combined contain approximately 13,000 volumes. It’s an incredibly rich resource and the best library around for many hundreds of miles. The diversity of his collection is astounding. There is a substantial collection of books on art and architecture, as one would expect, but in addition you find hundreds of books on astronomy, philosophy, literature, anthropology, geology, and so on. Judd’s writings reflect his reading practice. One thing we added to the book are footnotes that specify whether Judd’s library includes the volume from which he is quoting.

South Library, La Mansana de Chinati/The Block, Judd Foundation, Marfa, TX

Image: Elizabeth Felicella/Esto © Judd Foundation

Clark: Is a catalogue of the library available to scholars?

Murray: Yes, the Foundation provides digital access to the library catalogue by request.

Clark: Flavin, would you comment a bit more on the library?

Judd: It was about knowledge and things to look at, to study and learn from. It didn’t matter where it came from or what time, there wasn’t a concern with any “style.” Don had respect for things that he could learn from; that is why we have Icelandic sagas and the complete sets of Loeb classics. He found the Icelandic sagas fascinating and beautiful and the Loeb books a basic requirement of anybody in western civilization. You have to know how you are built to change who you are and to make things that don’t exist yet that only you could make.

Clark: One of Judd’s early published articles was a review of Josef Albers’ Interaction of Color in which he comments, “the plain fact of color in art, the specific use of these effects in art, which is contemporary, and Albers’ experimental way of teaching color are the real contributions of the book.” Visitors to La Mansana de Chinati, the city block of buildings in Marfa, which Judd renovated as a residence and series of studios, notice that Judd was a serious collector of Albers’ work, integrating the paintings into a number of his living and working spaces. How would you characterize the importance of Albers for Judd?

Murray: It is my understanding that Judd’s appreciation for Albers grew over time. I think the best way to understand this is to read Judd’s 1991 essay, “Josef Albers,” which can be found in Donald Judd Writings. Judd notes that he never met Albers in person but he has “seen a lot of paintings by Albers, often singly, over half the world. They are always amazingly beautiful.” In addition to the many volumes of books Judd collected on Albers, he also installed three paintings and two prints by Albers in his Architecture Studio, the former Marfa National Bank in Marfa – a beautiful building from the 1930s.

Judd: Don’s appreciation of Albers evolved over time. He bought most of the Albers paintings not in the sixties when they were dirt-cheap (he had no money) but in the eighties when they were still affordable. Don was a serious collector of anything he liked and Albers, of course, is very consistent in his quality. In the early eighties Don was working on the painted metal works after years of only using one or two colors at a time. He embarked on the painted metal works because he specifically wanted to explore color more and this would have been the time of most of the purchases of the Albers works that the Foundation has.

Clark: In his work as a critic Judd did not hesitate to lament when he found work lacking – for example, he once commented, “double-barreled boredom is responsible for the vitriolic tone of this review.” Some of his harshest criticism was reserved for Robert Smithson, whose art he accused of “anthropomorphic sentimentalism” and whose writings he rejected in a concise letter to the editor of Arts Magazine. Have you considered why Judd’s reaction to Smithson was so pronounced?

Judd: Probably because he knew him so well. They went on a couple of day trips together, sharing an interest in geology and science. Don got to know Smithson’s thinking in a way that went beyond the typical review.

Clark: Judd championed many artists, including Lee Bontecou, Yayoi Kusama, and Helen Frankenthaler, yet of his contemporaries, he seemed to hold John Chamberlain in the highest regard. Can you speak a bit to that relationship as it surfaces both in the writings and in the installation of Chamberlain’s work in Marfa?

Judd: I think he held Chamberlain, Kusama, and Bontecou in equal regard but it was Chamberlain he was closest to. Chamberlain, like Don, also did very consistent work and Chamberlain’s work dealt with color and space together, Don’s major preoccupations, in a way that the others didn’t necessarily.

Clark: The themes of conservation and of permanence, stewardship of his art, architecture, and the spaces and landscapes in which these reside, together with the works of other artists whom he admired, are recurring themes in Judd’s writings. Can you discuss the way Judd Foundation is addressing these concerns and preserving Judd’s work for future generations? What are some of the ways that Judd Foundation continues to support the work of living artists?

Murray: Making Judd’s permanently installed living and working spaces available to the public is incredibly important to the Foundation. We offer guided visits of Judd’s spaces in New York and Marfa. In Marfa, due to increased demand, we now offer guided visits to Judd’s home seven days a week. In addition, we serve Judd’s legacy by being the key resource for his life and work, not only by making our archives accessible, but also through large-scale research projects, such as the Donald Judd Catalogue Raisonné project for which we initiated a public call for works. Moreover, Judd Foundation has opened up the first floor of 101 Spring Street for exhibitions. To date we have had exhibitions of work by Dan Flavin and James Rosenquist, as well as an installation of two site-specific terra cotta wall works by Richard Long. And we have more to look forward to. These exhibitions allow us to reflect upon artists that Judd respected, such as Dan Flavin, while also reflecting on contemporary artists whose work we feel, as Judd did, deserves recognition.

Further reading

Donald Judd, Complete Writings, 1959-1975 (New York: Judd Foundation, 2015).

Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray, eds. Donald Judd Writings (New York: Judd Foundation and David Zwirner Books, 2016).

For more information about Judd Foundation, visit http://juddfoundation.org

main image:

South Library, La Mansana de Chinati/The Block, Judd Foundation, Marfa, TX

Image: Elizabeth Felicella/Esto © Judd Foundation