ART IS A CONFRONTATION WITH A ‘ME’ THAT NEEDS IMPROVING

The Beginnings of the Noah Purifoy Foundation

Sometime in early 1998, Noah Purifoy called me to ask when I was coming to California next and if I could be sure to include a visit to his home and studio in my trip. He said he had something very important he wanted to talk to me about. I was curious to know what. Noah said he didn’t want to talk about it over the telephone, but after persistent prying on my part, he revealed that he wanted to start a foundation that could take over the sculpture park he was building at his home in Joshua Tree and promote his ideas about community-based art when he was no longer able to speak for himself.

I had met Noah ten years earlier when I organized an oral history project to interview African Americans artists in Los Angeles. I liked his work, and I started writing about him. I did an essay for the catalogue accompanying the retrospective that Lizzetta LeFalle-Collins curated for the California African-American Museum. His work at the California Arts Council was the focal point of a chapter in my book The Modern Moves West: California Artists and Democratic Culture in the Twentieth Century.

I knew absolutely nothing about artist foundations, but I agreed to serve as the founding president of the Noah Purifoy Foundation, mainly because Noah insisted. Sue Welsh, who had known him for thirty years and worked with him at the Watts Towers Cultural Center in the 1960s, served as secretary-treasurer. Sue took care of the abundant day-to-day tasks that needed to be done if there were to be a foundation that could protect and promote Noah’s legacy, all while trying to make sure that we didn’t interfere with his on-going activities. In the fall of 1998, we held the first meetings of the trustees and developed our initial plans. An attorney who knew Noah’s work volunteered to file the papers, and in early 1999, we had our state licenses and were officially operating.

The trustees wanted to get well-known artists involved, in part as a validation of Noah’s standing as a senior artist. We were particularly delighted when Joseph Lewis and Ed Ruscha joined the board. Lewis replaced me in 2001 as president, a position that he continues to hold. When Ruscha came out for the first time to see the sculpture park, Noah said something along the lines of, “Ed, I hear you’re an artist, what kind of work do you do?” It was typical Noah, and there was no way of knowing whether he was playing naive or had been so focused on his work that he was out of the loop. In any event, the two artists, very different in style and temperament, got along well. With Ed’s help, the foundation purchased the land where Noah had started building his sculpture park in 1989. Ed then purchased adjoining lots and donated them to the foundation. Noah had ten acres for the park that he kept working on until his unexpected death in 2004 in a fire that swept through his home.

Noah was born in 1917 in a small farming town outside Selma, Alabama. His earliest memories were of trailing behind his parents and twelve siblings as the whole family worked hot, humid summer days picking cotton. He left the South during World War II when he served in the Pacific front. When he returned home, he settled in Cleveland, where he used his GI Bill benefits to go to university and get a master’s in social work. After graduating, he worked primarily helping people with mental health problems adjust to independent living. In 1952 he decided to go to art school and was accepted at Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. He was the first African American to be admitted, and he remained an outsider there although Los Angeles had become a major center for African American creativity. He linked up with other African American artists in the city interested in abstraction and assemblage. He became part of a vibrant community, but did not want to be labeled as a “Black artist” or a “protest artist.” Yet, like many other African American artists, the civil rights and Black power movements reshaped his understanding of art, as, in a very direct and personal way had the urban unrest of the 1960s.

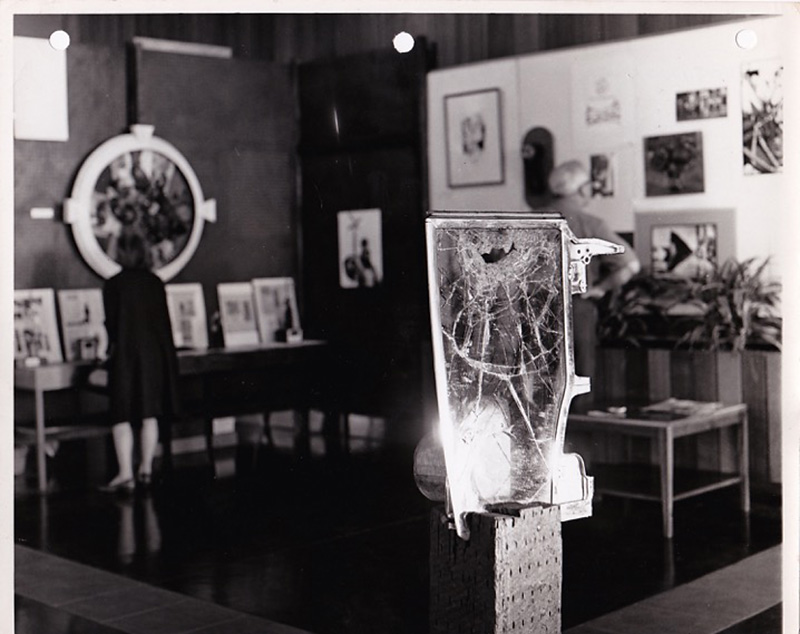

Noah Purifoy was the director of the Watts Towers Cultural Center in August 1965, when riots protesting police brutality spread across the community of Watts, eight miles south of downtown Los Angeles. Thirty-four people died during five days of armed conflict. Over four thousand people were arrested, and several blocks of the neighborhood’s main shopping district burned down. After the shooting and burning stopped, he led a group of students into the community to salvage debris from the rubble and create a series of assemblages that he exhibited in a show at the Watts Towers Cultural Center entitled “Sixty-Six Signs of Neon.”1 The title referred to neon signs from burned-out local stores that had melted into unsettling surrealist-like shapes. Purifoy cleaned and polished the glass drippings he found, mounted them, and presented them as elegant artworks that were also eyewitnesses to, and products of, the heat of the community’s anger.

Purifoy’s first one-artist show was held at the Brockman Gallery in Los Angeles in 1970. He arranged assemblages and other wall works into a series of tableaux reflecting topics such as crime, drug addiction, and prostitution – problems he saw as endemic to Black communities, particularly in South Central Los Angeles. “Art as an escape from the world, that’s wrong,” he explained later. “But escape is what most people want. Art should be a confrontation with a ‘me’ that is always in need of improving.” However, Purifoy was not sure that working as an artist was an effective way to make his community a better place to live. He had become convinced that critics and the public simply did not want to see him as an artist with something to say that only an artist could. They expected him as an African American artist to make protest art. He had no interest in doing work that might get attention but would contribute nothing to public life. Breath of Fresh Air, for example, composed from two joints of stovepipes with part of a tin and tarpaper roof mounted on the peak, expressed his love of pure form, but he was convinced that it was more than technique. The parabolic swoop of the lower leg and the pliable molding of the upper portion have the majesty of shapes normally associated with aluminum or other high-tech materials. The piece worked to demolish preconceptions that only the most modern materials could be sleek or that junk must be nostalgic remnants of a fading past. Purifoy challenged his viewers to see that even the humblest materials found in the most distressed circumstances could possess the grace usually associated with modern technology.

Art, he thought, had become narrow. It spoke only to relatively small groups of privileged people. In particular, the art world, even when it recognized African American artists, still largely excluded most Blacks and most poor people from its public. If the knowledge that artists gained was to be made more broadly available, less emphasis had to be placed on the completed work and more on the thought process inherent to the making of art. He argued that, “where we made our most serious error historically was that nobody chose to evaluate the creative process in terms of its applicability. Is it applicable to anything other than the making of art? That’s the question I asked myself as I went on this long search.”

In 1976 his ideas about broadening the functions art practice played in society brought him to the attention of Governor Edmund G. “Jerry” Brown, Jr., who appointed Purifoy to the California Arts Council, a new state agency that at the time was run by and for working creative people. During the eleven years he sat on the council, Purifoy made no art himself. Instead he threw himself into developing a broad range of pilot artist-in-communities programs that quickly expanded into artists working in prisons, schools, hospitals, and senior centers. He dreamed of redirecting artists back to the challenge of addressing their work to a larger, uninitiated community. “I was looking,” he explained, “for another vehicle to see to what extent one single person can effect change in the large world that we live in … it was easy for me to give up art and never anticipate going back to that, because I could spend the rest of my life trying to find a means by which one can synthesize the left brain with the right brain and come up with some kind of profound concept about how people learn what they need to know to exist in the world.”

Purifoy’s self-imposed exile from the practice of art ended in 1987 when he retired and moved to an artist’s cooperative in downtown Los Angeles, but he needed a cheaper place to live. With considerable trepidation, in 1989, Purifoy accepted Debby Brewer’s invitation to move over a hundred miles east into the Mojave desert and share her lot in Joshua Tree, California. He set up a mobile home and built a workshop for himself. His first response to the terrain was negative. “It just gives the impression of desolation and sheer poverty.” As he lived there longer, he discovered a rich variety of life surrounding him in every direction. Hosts of busy animals and a plethora of natural processes that had been completely invisible to him slowly revealed themselves. His response to the desert provided him with an all-encompassing metaphor for puzzles he had pondered all his life: what is the relationship of selfishness and blindness? What are the conditions by which relationships are patterned into meaningful designs? How can art promote the mutual recognition that is the necessary condition of knowledge and communication?

Working as an assemblagist in the desert proved to be a radically different experience from working in Los Angeles, where sooner or later everything is thrown away as junk or garbage. In Joshua Tree, everything seemed to be recycled. To find materials, he took part in the weekly swap meets where his neighbors exchanged belongings they no longer needed or wanted.

People began stopping by to learn from him, some providing the heavy manual labor that he needed to complete the increasingly larger-scale projects, others dropping off their refuse, such as old refrigerators, broken washing machines, automobile parts, computers, and other electronic equipment that no longer worked. One plumbing contractor donated several dozen toilets that could no longer be installed in California due to changed water-conservation laws.

The first pieces done in Joshua Tree were large stand-alone sculptures with considerable elegance. Constructed with shiny metal sheets and decorated with simple building construction materials such as heating duct tubing, Purifoy returned to ideas motivating Breath of Fresh Air twenty-five years earlier. He spaced his sculptures around his site, setting them against the different vistas on the property of distant mountains, valleys, and desert flatlands. Adding a humorous touch, he connected several of the large standing sculptures with Kirby Express, a two hundred-foot-long railroad line made from aluminum tubing for a train constructed from broken vacuum cleaners mounted on bicycle wheels. Another humorous piece, The City, consisted of tall, brightly colored skyscrapers rising above the Joshua trees on the property, constructed from dozens of yellow and green lunch trays.

Noah Purifoy, The Kirby Express, 1995-1996

Mixed media (aluminum beer kegs, baby carriage, smudge pot, bicycle wheels, found objects), with The White House 1990-1993 in the background

Photograph courtesy of the Noah Purifoy Foundation

Purifoy wanted the harsh high-desert weather, with its constant winds, 110-degree-plus heat in the summer, and frequent overnight freezes during the winter to be an integral part of the sculpture park he was developing. He erected a thirty-foot-long, twenty-foot-high scaffolding in which he suspended sheets of brightly colored metal. In this piece, which he titled Mondrian, he wanted to start out with a straightforward imitation of one of the constructivist masterpieces of the well-known Dutch modernist. Season after season, wind, rain, and hailstorms were to rearrange the piece. Whenever Mondrian lost its formal coherence and could no longer be seen as the product of a dialogue between an art idea and a tough natural environment, Purifoy reconstructed it and the process resumed. A very different piece took shape in a large twenty-foot-square field, where Purifoy pinned down old shoes and clothes that he had collected into a large textile collage. Initially, he wanted the piece to have the rich colors and textures of a Bonnard or Vuillard painting. He expected that over the space of several years, weather and the work of animals would dull the colors and pull the materials back into the soil. The initial vision was to remain detectable in the juxtaposed shapes etched into the desert sand, but the climate enacted a form of art historical transformation as the piece assumed the look and feel of a 1950s abstract painting by Dubuffet, Fontana, or Burri.

Noah Purifoy, Untitled (Sculpture Design in A Mondrian Fashion), 1992

Mixed media, 6 x 8 ft

Photograph courtesy of the Noah Purifoy Foundation

Juxtaposed against the pieces defined by Purifoy’s reflections on modern art were other works with more direct social comment. Voting Booth presented a row of old shoes standing in three stalls behind drawn curtains. An iconic image of democracy in action is transformed whenever the wind lifts the curtain to reveal a row of toilets in place of voting machines. Nearby is Aurora Borealis, an assembly hall built around a printer’s plate with the first page of the Declaration of Independence that has been broken in half suspended from the ceiling. A speaker’s platform, decorated with the stars and stripes of the national flag, takes up one side of the room. Next to the platform is a fragment of a large store sign that Purifoy had found sporting the words “Today, It’s Simple, Convenient.” In one corner of the hall, Purifoy added a sunken garden of broken plate-window glass. He built a wall facing due west from glass bottles that burst into bright colors as the sun lowers in late afternoon. Outside the assembly hall by the front door is a water fountain labeled “White” placed next to a broken toilet bowl labeled “Colored,” a reference to the segregated public facilities of the South when he was growing up. Purifoy emphatically denied that the work was “protest art,” insisting that he was only representing simple historical facts.

Noah Purifoy, Voting Booth. Photo by Spare Parts and Pics

The questions Purifoy grappled with in the sculpture park were those that had puzzled him throughout his life. On the series he made from automobile and truck radiators that he took apart and then reassembled as abstractions, he observed:

When you see a radiator, you don’t see what’s exposed here. You see a rectangular or a square object, with tubes running out of it. That’s what you see. When you do art, you see beyond the object. That effort of seeing beyond the object is also present in human relations. You see beyond the individual into what he/she thinks and feels. … But looking at a radiator in a car, how often do we immediately transfer to the absence of knowledge about another human being who strikes us as being problematic, just like a radiator in a car, and want to know his full function, his behavior, in relationship to me or anyone. The relation is peculiar, meaning I don’t thoroughly understand my relationship with the human being. But I do thoroughly understand the function of a radiator in a car. Now, why doesn’t the function of a radiator in a car stimulate me to want to know, or transfer?

The quote comes from an interview I did with Noah at the end of 1998, the first of many conversations with Noah that I recorded over a four-year period. If I was going to be president of a foundation dedicated to his work and thought, I needed to dig into what the priorities he gave to his work. I was not surprised that Noah expressed at times contradictory ideas about what he had done and what he wanted to happen. His ideas were not incoherent, but contradictory in basic ways that reflected the different strands of his art practice and his life experience. He was always a difficult person to interview, and our efforts to define his priorities were no different because his gut reaction to my questions was to challenge presuppositions that my queries seemed to indicate. He was intent to make the task of the foundation difficult because contrariety was integral to the person he had been all his life. When I asked a question related to formal elements in several of his pieces and whether those pieces needed to be conserved in a different way from pieces that he had made to interact with the environment, he snapped at me that obviously I wasn’t listening properly:

Why do people go to the artist and want to know why he did something? They can’t understand the work. Sometimes they get an answer, sometimes they don’t. Now, the reason they go away dissatisfied, if that be the case, is that they have not explored life to the extent whereby, whatever you conclude behind observing the work is probably okay with the artist. You don’t have to go to the artist for any reason. My answer would have been they go to the artist because they want something they don’t otherwise get from the work. Outstanding reason is, I don’t understand the work, and I want to hear from the horse’s mouth what the hell it means. And often times, when you hear from the horse’s mouth, you’re still not satisfied, because you still have disturbing feelings. Now, what the artist ought to have the intelligence to know and say directly, “You’ve gotta get your shit together, because mine is together. You see it evident right there. Now you get your shit together.” That’s a good answer. But a rather disturbing one, I’m sure … I am a liaison between you and the world you live in.

I agreed with Noah completely that the art spoke for itself and that the board had to move from the feelings each of us formed for the body of work Noah was leaving behind. This is probably a universal situation for anybody who has become responsible for an artist’s legacy. We hope to follow what he or she would have preferred, but our decisions in the end spring from our own deeply personal reactions, as well as the limitations of any given practical situation. Noah understood that nothing he said in words could exhaust what the work itself said more eloquently. Each of us coming to a piece of art that has moved us add something important to what it has said, but even the sum total is still a fraction of what the artwork has left to say.

1 The catalogue for the show, Junk Art: Sixty-Six Signs of Neon, has been reprinted by the California African American Museum in Los Angeles.

Further Reading

For more on the Noah Purifoy Foundation, visit http://www.noahpurifoy.com.

Richard Cándida Smith, The Modern Moves West: California Artists and Democratic Culture in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009).

Kellie Jones, Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980 (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum,2011).

Lizzetta LeFalle-Collins, Noah Purifoy: Outside and in the Open (Los Angeles: California African American Museum, 1997).

Rebecca Peabody et al. Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles Art, 1945-1980 (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011).

Noah Purifoy, Noah Purifoy: High Desert Assemblage Artist (Göttingen: Steidl Publishers, 2015).

Franklin Sirmans, Yeal Lipschutz, Kristine McKenna, Lowery Stokes Sims et al. Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2015).

Daniel Widener, Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles (Duke University Press, 2010).

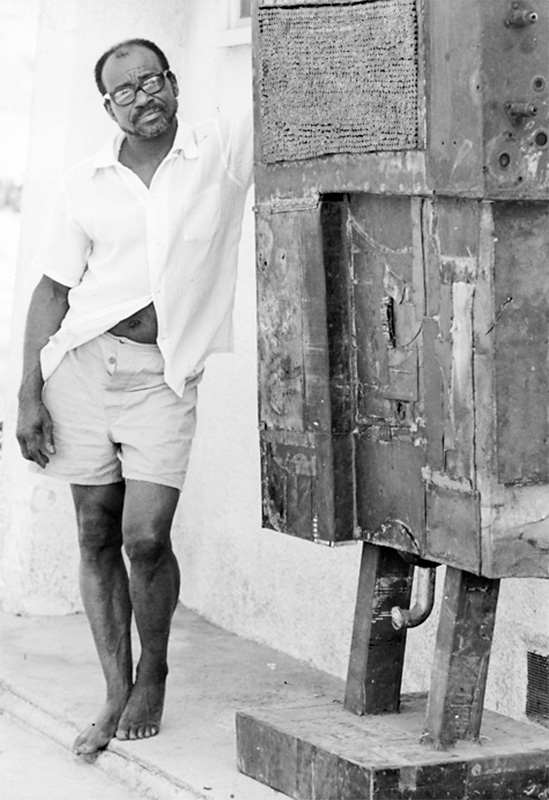

main image:

Portrait of Noah Purifoy sitting on The White House, 1990-1993

Photo courtesy of the Noah Purifoy Foundation