ALL REZ

Community-Based Museology through Creative Placemaking

What does it mean to be ALL REZ? For Rapheal Begay (Diné), ALL REZ is the act of returning home and celebrating the beauty, strength, and vitality found in his backyard. It is an opportunity to remember, listen, and embody a curated moment between Diné (Navajo) photography, oral history, and relatives.

Emergence

What does it mean to be ALL REZ? For Rapheal Begay (Diné), ALL REZ is the act of returning home and celebrating the beauty, strength, and vitality found in his backyard. It is an opportunity to remember, listen, and embody a curated moment between Diné (Navajo) photography, oral history, and relatives. It is a reservation-based phenomenon developed with creative place-making, visual sovereignty, cultural stewardship, and intergenerational storytelling in heart, mind, and spirit.

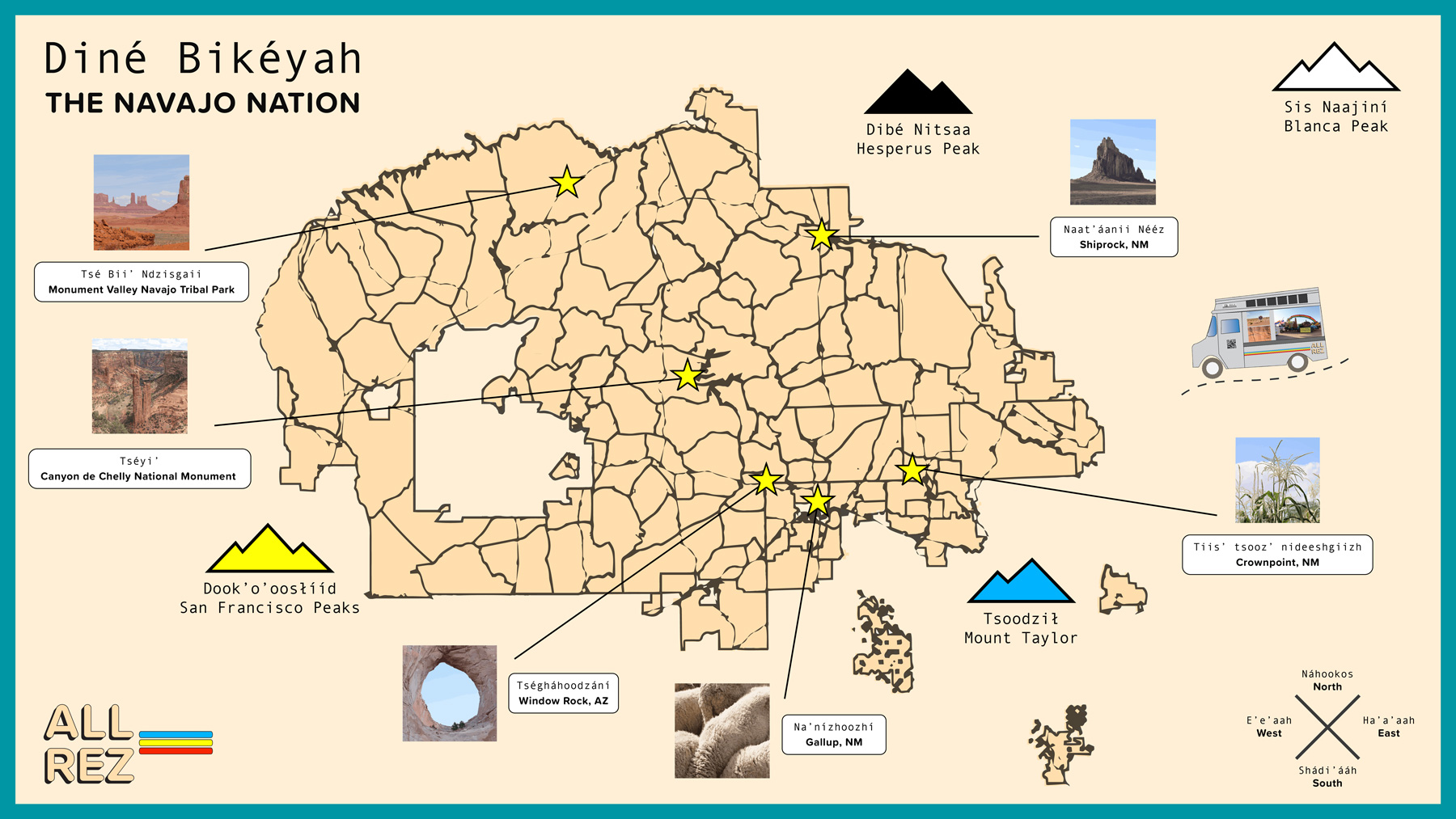

Curatorially, ALL REZ: Kéyah, Hooghan, K’é, Iiná / Land, Home, Kinship, Life was a traveling, site-specific, experimental photography exhibition and collaborative museological project during the summer of 2024. An exercise in creative place-making with the goal of fostering active storytelling, ALL REZ centered the voices and experiences of Diné community members, offering a reciprocal process of exhibition-making. Fundamentally–as a project that posed more questions than answers–we aimed to mold a new, Diné-driven model for the stewardship of contemporary art and storytelling. Here, museums, along with the items they hold and exhibit, are brought out of urban spaces and co-curated with communities.

Practically, ALL REZ was a multi-sited exhibition and collaboration between Axle Contemporary, a mobile artspace in a retrofitted aluminum van based in Santa Fe, New Mexico (June 1–30, 2024); the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology (Maxwell) in Albuquerque (May 4–July 27, 2024); photographer and curator Rapheal Begay in Window Rock, Arizona (ALL REZ photographer, lead curator, and creative director); and museum anthropologist and independent curator Lillia McEnaney (ALL REZ co-curator and project manager), also in Santa Fe. Institutionally, Matthew Chase-Daniel (Axle), Jerry Wellman (Axle), Toni Gentilli (Maxwell), Chris Albert (Maxwell), and Dr. Carla Sinpoli (Maxwell) were facilitators and thought partners. Now more than ever, it is important to recognize that we received generous funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional support from the Alfonso Ortiz Center for Intercultural Studies at the University of New Mexico and in-kind assistance from our partner organizations, gallupARTS and the Navajo Nation Museum.1

This essay includes a concert of voices and reflects the differing positionalities and perspectives of our curatorial team as a collection of both Diné and non-Diné curators and artists. It also reflects one of the exhibition’s primary goals: to dismantle the curatorial voice of authority to create tangible spaces for the multiplicities of meaning that emerge in community contexts.

Histories and Constructions

The history of Diné photography began with imprisonment. The first photographs of Diné were taken at Hwéeldi, where survivors of Kit Carson’s genocidal campaign were incarcerated as prisoners of war from 1863 to 1868 until they successfully negotiated their freedom on June 1, 1868 (the travelling ALL REZ kick-off date was June 1, 2024). Captured–both physically and metaphorically–in space and time by military personnel and government photographers, the first photographs of Diné show individuals being watched by soldiers and receiving food rations.2 The language of photography itself reflects the medium’s origins in the racist, imperialist agenda to dominate Native communities, with terminology such as the “shot” and the “captured” image reflecting the captivity Diné resisted against at Hwéeldi.3

By the early twentieth century, over 175 photographers had traversed over and staked a (false) claim on Diné Bikéyah (the Navajo Nation).4 This history reflects a broader pattern in the representation of Native communities throughout the so-called United States: non-Native photographers traveling ever westward aimed to document what they believed were the ‘last traces’ of the ‘authentic Indian.’ Influenced by the teachings of social Darwinism and belief in Manifest Destiny–and emboldened by federal policies of extermination–recurring themes such as the ‘noble savage’ and the ‘vanishing race’ dominated the construction of Indigenous representation. Such biased and harmful visual rhetorics–made ‘true’ through the evidentiary sway of Bilagáana (white) photography–became a principal means through which non-Native audiences encountered and constructed what they thought they knew about Diné communities. In doing so, both photographers and their images positioned Navajo subjects within colonial frameworks, rendering them legible in ways that aligned with outsiders’ imperialistic worldviews rather than Diné senses of self, community, and sovereignty. Indeed, transformative Palestinian and American scholar-activist Edward Said reminds us that these material ‘evidences’ of white supremacy carried real sociopolitical weight in the Western world, for they were–and still are–activated and weaponized by settlers to justify the genocidal treatment of Native Nations.5 These same practices are prevalent in the portrayals and treatment of Indigenous people by museums, anthropology, and art history.

Visual anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards argues that “photographs are as much ‘to think with,’ as they are empirical, evidential inscriptions.”6 What then, does it mean to think with Begay’s photography? Here, we argue that Begay’s body of work–as “material objects to which things happen”–are active agents in the physical performance of sociocultural life.7 How were these images made, circulated, catalogued, and exhibited, and why does it matter? How does installing this body of work in community spaces, from flea markets to tribal parks, affect the impact and lifespan of the photographs–and by extension, the exhibition? What can ALL REZ, as both an Indigenous-led, collaborative curatorial concept and a physical exhibition occurring simultaneously in multiple spaces, teach us about the generative power of self-representation and community-responsive curatorial interpretations?

Site- and Sight-Specific Movement

In summer 2024, the ALL REZ team launched two parallel but distinct exhibitions. One installation was on view at the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology with explicit discussions around the history of photography of and by Diné together with community-based museological praxis. Here, visitors could engage with six large-scale prints of Begay’s photographs, a map of Diné Bikyéah showing the route and stops of the traveling exhibit, and a slideshow–updated weekly–with photos of community members interacting with the team on the road.8 The second, primary, exhibition consisted of Begay’s photographs installed on, inside, and around Axle Contemporary, a mobile art gallery housed in the back of a custom retrofitted 1970 aluminum stepvan.

ALL REZ began as a memory and eventually manifested into a dream come true. For Begay, growing up on the Navajo reservation, the idea of a traveling, mobile photography exhibition was inspired by culturally-responsive floats exhibited at annual fairs and parades, and the use of large-scale images of Diné Bikéyah on the sides of local transit buses.

The interior of Axle was transformed into a welcoming space for reflection and conversation with the artist. Meant to evoke the interior of a hogan, a traditional, sacred space, the van was overflowing with books about Indigenous photography, museums, and anthropology, comfortable seating for conversation, and images from Begay’s personal collection. Outside, fourteen photographs were mounted on seven double-sided A-frames, extending the walls of the gallery into the physical landscape, activating the multiplicities of meaning within space, place, and time. In a deliberate contrast to conventional museum practice, no labels, text panels, or gallery guide accompanied the installation. For ALL REZ, interpretation was instead defined by reciprocal storytelling. The photographs were vessels for collaborative meaning-making that could not exist without our shared engagement(s) with the work. This active back-and-forth between visitors, the work, the gallery, and the project team created the whole: an ALL REZ micro-community.

In June 2024, we drove the van throughout Diné Bikéyah in a clockwise fashion, following the path of the sun and mirroring how one would move within a hogan. Starting from the east and moving within the four sacred mountains and centered around kéyah (land), hooghan (home), k’é (kinship), and iiná (life), ALL REZ traveled across and between the colonial boundaries of New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, stopping at a variety of Diné community gathering spaces. Starting in Albuquerque, we traveled west to the Crownpoint Rug Auction on the campus of Navajo Technical University in Crownpoint, New Mexico; continued down the road to Gallup’s weekly flea market and monthly Arts Crawl; over the state line to Ch’ihootso Indian Market Place (also known as the Window Rock Flea Market) and the Navajo Nation Museum, both in the capital of the Nation, Window Rock, Arizona; up the road to Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Chinle, Arizona; up even further north to Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park; over to Shiprock Flea Market in Shiprock, New Mexico; and finally, returning to where we began, to Santa Fe: parked outside of the Southwest’s leading contemporary art museum, SITE SANTA FE; and lastly, one of the earliest centers of anthropological research in the Southwest, the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture/Laboratory of Anthropology atop Museum Hill.

By installing the exhibition at both culturally significant sites and seemingly mundane community spaces, we aimed to honor Diné values of community and kinship. For example, on Diné Bikéyah, flea markets are not only places for economic exchange, but also spaces to deepen cultural connections through the sale of plants, medicines, and ceremonial supplies, and through the sharing of food, physical proximity, and conversation. Bringing ALL REZ to these gatherings felt apt, and much more appropriate and effective than presenting Begay’s body of work at a museum or other ‘art’ institution. This purposeful refusal of the static art museum was indeed intentional and central to our thinking. What does it mean to bring an exhibition to a parking lot? How will visitors conceptualize and engage with the work in this context in new and generative ways? How will the exhibition–and its photographs–change as they become imbued with new visitors and contexts?

This month-long journey reunited Begay’s photographs of his homelands–often displayed in Western museums across the United States–back to where they belong: at home. As Diné visitors entered the stepvan and engaged with Begay and his images, memories were evoked and stories shared, thus co-creating and co-curating the exhibition.

Creative Place-Making

On June 7, 2024, at the Crownpoint Rug Action, Renata Yazzie (Diné), a PhD student in ethnomusicology at Columbia University, was drawn to Origin (Tsé Náshchii’ – Hunter’s Point, AZ), 2017. Reflecting on the relationships between sound and photography, Yazzie imbued Origin with an entirely new sensory experience:

RY: Yes, and, so, part of my dissertation is thinking about listening. And, when I see that photo not only can I smell it, but I can hear it. I know exactly how that truck sounds.[…] I am familiar with [the] landscape in that area. I can hear what the ground sounds like when I walk on it, I can hear what the weed sounds like when they’re going in the wind. I can hear the sound of my own grandmother’s front door opening and closing. And how hard those windows are to open and shut because my grandmother, my grandparents also had a VA house. Which, they actually did live in until much later in their life.

RY: And, each of these photos have that same possibility. I mean, [the] creakiness of the wheelbarrow, the sound that the wires make when you’re closing the gate and the way they drag across the sand, and the way that when you throw a rock at the tire, the way that bounces off, the sounds that makes. All of those things are all indicative of home for me. So each of those sheep have their own particular way that they sound, they have their own cry, they have their own bleat. They individually have their own voices. So, it’s really…I like to think about photographs in the capability of the sounds that are captured in that one particular millisecond.

RY: Yeah, thank you for bringing this exhibit out here. This is really great.

During the conversation, Begay shared that he had never thought about photographs in this auditory way. In practice, Begay speaks to the work by way of memories, stories, and teachings, yet it was here that we understood the image also speaks back. Similar to his relationship to the Diné cultural landscape, the images allowed visitors to engage through a site/sight-specific process that encouraged each of them to reflect and remember. What does it mean to relate to the photograph through the gifts bestowed upon us by Diyin Dine’é (the Holy People): our five senses? This journey was developed with respect, intention, and a willingness to love, cry, laugh, and coexist with not only those who experienced this initiative, but also with the site/sight shared.

Later that day, Begay and Shyler Martin (Diné)–inspired by Rez Dog (Tsé Náshchii’ – Hunter’s Point, AZ), 2017–connected around personal and professional experiences with the mental health services on the Navajo Nation. In a previous exhibition at the Maxwell, Begay wrote of how Rez Dog speaks of resiliency: “as we avert our gaze from shaggy rez dogs and unsheltered relatives, I cannot help but wonder where we are headed. It is through education, expression, and emotion that I believe we can curate the future and honor our humanity.”9 With respect to our holistic relationships as Diné bíla’ ashdla’í (Holy Five-Fingered Beings), the conversation focused on our connections to not only one another but also to our non-human relatives, including animals, plants, and the natural elements. As part of ALL REZ, Begay posed the question to Martin: “How has Rez Life (reservation-based life) made you resilient?”:

SM: I took the Rez Life, and I, myself, sort of was just like, “I want to get out of here, you know”. And then I was out there [at New Mexico State University], and then meeting a diverse group of people, as well as different tribes, and then just hearing what they had to say. And it had similarities. […] And at the same time, it was like, “Oh man, I want to go home, I want to be home.” And then I realized that, because of my grandparents, because of my mom, the things that were done in the home the way it was done, the discipline that was there, grandma and grandpa doing things the way that they did […] turned me into this individual now searching for things to improve the Navajo Nation, things to improve our law system.

SM: And they say that our Diné culture, our language, is going to slowly die out, and I don’t know if it will, but if it does, what is it going to come down to for us to reconnect with that language? What are we going to do to try to rekindle that flame and with that resiliency there, in myself and among non-Native people, out in Las Cruces, and out in border towns and everything? I’m proud for who I am and I love who I am now, and when I speak up and I say what’s on my mind, and I wasn’t able to do that before.

SM: […] I’m here because of my parents, my father, my mom, my ancestors; they fought for everything that they did. And, you know, I’m here because of them, and what am I gonna do if I give up?

SM: You know, they were resilient, and this is built here.

Throughout the ALL REZ journey, it was these shared moments that expanded our understanding of the questions posed, as well as our individual horizons. Personally, Begay related to Martin’s realization that time away from home allowed us to appreciate rez life. Since returning home in 2018, the creation of these images has developed into forms of acceptance of all that the reservation has to offer. Based on this conversation, the term resilience can be described as a form of self-determination within a state of hózhó (harmony and balance), despite the everyday challenges of iiná (life). Rez Dog now embodies the reciprocal exchange between Shyler and Begay, and has expanded upon notions of acceptance, mindfulness, and healing that warrant each of us to do more. As Holy Earth Surface People, we each have an opportunity to steward our relationships to not only ourselves, but to our language, our culture, and our shared history.

By generating what Edwards calls “little narratives,” that are “constituted by and are constitutive of the ‘grand’” narrative, ALL REZ created a discursive space through which Diné sociocultural politics were rendered not only visible, but activated.10 It is through these narratives–both little and grand–that an exhibition took shape: an exhibition that transformed and metamorphosed along with each individual photograph within. In particular, Begay did not anticipate the project’s cumulative exchange of energy and sense of healing through active storytelling and Indigenous relationship building. ALL REZ was physically (through the physical location of where the van was parked and the ever-changing installation of the A-frames) and rhetorically (through iterative conversations with Begay) different for each person who experienced it, on and off the Navajo Nation.

This is a marked and intentional reversal of the curatorial process. Rather than presenting Begay’s work with descriptive labels, artist statements, or authoritative curatorial interpretations, our goal of having the exhibition’s narrative created by and for the visitor was achieved. This opened up a space for critical engagement and reflection on the stewardship and circulation of public art, its interpretation, and broader cultural impacts. As visitors engaged with the project team in and around the van, conversations ranged from Indigenous visual sovereignty and storytelling traditions, to Diné land-based knowledge, education, healthcare systems, and so much else. Diné community members and other visitors expressed gratitude for the project and reflected on its importance:

Anonymous visitor (Diné), Shiprock Flea Market: I like to see things like this. It’s nice to see that we’re using art in different ways to preserve our culture and remembering who we are. It’s really important, especially for our urban kids, you know. They do hear where they come from and who they are. Because for them, it’s hard, you know they’re trying to be in two worlds. Trying to live that city life and then, when they come back to grandma’s you know, they’re trying to balance that like, “who am I?” So, yeah, I saw the post online, so I told my husband. I was like “let’s go.”

Anonymous visitor (Diné), Shiprock Flea Market: This is kind of the first thing of its […] kind, bringing the art back to the community that it comes from, rather than displaying it, curated by others.

In response to the extractive and harmful histories of museums, photography, art history, and anthropology, for Begay, ALL REZ was envisioned for Diné people in mind, body, heart, and spirit. It is a gift to them. It is a rez-based phenomenon that can only happen with living on the reservation and being a part of the community, rather than a Bilagáana coming to visit for the summer, taking photographs, and saying ‘look at what Navajo people are.’ Kéyah (land), hooghan (home), k’é (kinship), and iiná (life) are universal ideas that his Diné and non-Diné relatives can connect to and understand–regardless of where they find themselves within or outside the four sacred mountains. The curated collection of images resembles the universal qualities of vernacular and mundane, intimate moments. They are reminders of the joys in life and that we each create beautiful moments to hold and to share. At the last stop on the Navajo Nation in Shiprock, New Mexico, a community member reflected on the ways our surroundings inform and inspire our presence:

Anonymous visitor (Diné), Shiprock Flea Market: Even though it’s not our grandma’s house, it brings that memory back of like, “Oh, how was my grandma’s house?” This is how my grandma’s house was.” You know, you start to run through it. It runs through your head, and those memories come back again for you not to forget. It kind of brings back that memory. And, “Don’t forget who you are,” “That’s who you are.” In our minds that comes, “Oh, this is who I am in here.”

The photograph acts as a mirror, a reflection, and a refraction of one’s lived experience. The image can be more than what we see; it can be about what we feel, or what we remember, or, more importantly, how we relate to the world. The image becomes a conduit for storytelling, but it is also an embodiment of the art of gathering–the gathering of ideas, emotions, memories, and stories.

Photographer and scholar Will Wilson (Diné) has frequently asked: “what if Native people invented photography?” If so, Begay believes that photography would have evolved into a storytelling tool inherently rooted in Indigenous values of respect, reverence, reciprocity, and responsibility. The camera would be a relationship-building and meaning-making technology used to preserve and steward the beauty and strength of our ever-changing communities. Reflecting on this move away from extractive photographs of the ‘Other’ and towards Navajo visual sovereignty, Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (Diné) tells us: “No longer is the camera held by an outsider looking in, instead the camera is held with brown hands opening familiar worlds. We document ourselves with a humanizing eye, we create new visions with ease, and we turn the camera and show how we see you.”11

Reflections

Driving, parking, talking, and driving again, ALL REZ was confronted with the immeasurable physical beauty of Diné Bikéyah in concert with generative conversations with those who have lived here since time immemorial. Throughout this process, our curatorial team held a feeling of weaving something across the land: sparking connections and evoking beauty and meaning through our physical presence and movements through day and night, mountains and deserts, sunshine and flooding watercourses–a reflection in and around the mobile artspace of where we were and why we were there. Aye…that’s ALL REZ.

Ahéhee (thank you).

1. Like so many of our colleagues, on May 2, 2025, we received notice that our NEA grant was terminated. Our termination date was May 31, 2025, which was the already-established end date of the grant, and the termination letter says that our project did not serve NEA’s new mission, which includes “supporting Tribal communities.” By the time we received this termination, the funds were entirely spent. This ridiculous termination prompted us to appeal. At the time of writing, we have not received further communication from the NEA.

2. Jennifer Nez Denetdale (Diné), Reclaiming Diné History: The Legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007).

3. James C. Faris, Navajo and Photography: A Critical History of an American People (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 14.

4. Ibid., 150.

5. Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979).

6. Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Routledge, 2021), 2.

7. Amiria Henare, “String Games,” in Museums, Anthropology, and Imperial Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 48.

8. This iteration of ALL REZ was in conversation with a separate but related exhibition, Nothing Left for Me: Federal Policy and the Photography of Milton Snow in Diné Bikyéah, co-curated by Dr. Jennifer Nez Denetdale (Diné) and McEnaney. In this space, visitors to the Maxwell were confronted with and urged to think with two distinctive points of view: the story of a non-Native photographer, Milton Snow, documenting a period of intensive Diné historical trauma, and Begay’s Diné-centered curatorial and artistic vision of sharing the beauty of his own community with his own community. For more about this project and related efforts, see: miltonsnowphotography.com.

9. Excerpt of exhibition text, A Vernacular Response: Photography of the Navajo Nation by Rapheal Begay, curated by Dr. Devorah Romanek, former curator of exhibits, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, 2019.

10. Edwards, Raw Histories, 3.

11. Jill Ahlberg Yohe, Jaida Grey Eagle, and Casey Riley, eds., In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 To Now (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), 46.

Main image

ALL REZ outside Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park, June 2024

Image description

An aluminum stepvan is parked in an otherwise empty parking lot in a desert landscape. Only the back of the van is visible. It has two back doors, each with a window, and both doors have an image of a desert landscape pasted across them. Towards the top of the van are three signs: “ALWAYS ONLINE AT AXLEART.COM,” “RAPHEAL BEGAY,” and “AXLE CONTEMPORARY.” Additionally, there are two signs on each side of the doors, one which reads “ALL REZ” in beige block letters with three stripes to the right of the letters – one bright blue, one yellow, and one red – and one which reads “KÉYAH, HOOGHAN, K’É, AND IINÁ” atop three stripes that match those of the other sign, and “LAND, HOME, KINSHIP, AND LIFE” below these stripes. Just above the bumper is a sign that states “WATCH YOUR STEP” and a New Mexico license plate that reads “AXLEART”. The ground of the parking lot is a dark gray asphalt, and short barrier of blocks of deep orange earth demarcates two sections of the lot. In the distance is more orange earth, sparse some green vegetation, a light post, and few parked cars, as well as a tall rock formation in the far distance. The sky is a clear blue, deepest at the horizon, with some streaks of pale pink and gold and sparse clouds throughout.