A Performance of Code

Rhizome and the Rise of Internet Art

Rhizome is a Greek word that refers to a mass of roots or the part of a plant that is continually stretching and expanding underground from unending nodal points. It also defines both the material and the approach of Rhizome the organization, founded by artist Mark Tribe in 1996 as a community-oriented and non-hierarchical champion of net art. In the intervening years, Rhizome has commissioned more than 100 artworks and launched a digital preservation program focused on software development. They have also reached audiences beyond the browser by curating exhibitions and organizing major public events such as the flagship conference Seven On Seven.

Rhizome is an affiliate in residence at the New Museum in New York City. The two organizations entered into a formal partnership in 2003 as part of a shared commitment to exploring the field of art and technology.

Art historian Gloria Sutton invited Rhizome Executive Director, Zachary Kaplan to meet with graduate students in Northeastern University’s Interdisciplinary Arts MFA program. The seminar focused on critically examining the popularization of the Internet around 1989 as a key flexion point in the production, distribution, and reception of contemporary art and critique capacious terms such as “post internet art.” Like VoCA itself, the seminar sought to consider what art actively does as it enters into the circulatory networks of public life. To this end, Kaplan discussed Rhizome’s recently launched Net Art Anthology, a two-year online exhibition representing 100 artworks from net art history, many of which were previously inaccessible. Taking on the complex task of identifying, preserving, and presenting exemplary works in a field characterized by broad participation, diverse practices, regular collaboration, and rapidly shifting formal and aesthetic standards, the Net Art Anthology has preserved twenty seven works of art to date. Below is an edited and condensed version of the conversation that transpired in Boston on April 5, 2017.

Gloria Sutton: Why did Rhizome decide to launch the Net Art Anthology last year?

Zachary Kaplan: We launched Net Art Anthology in 2016 to mark Rhizome’s 20th anniversary. The program is meant to be a capstone for two decades of work, an engine for further research, and a model for online exhibition-making, particularly involving artworks dependent on legacy software. There have been major exhibitions of internet art in the recent years, but gallery exhibitions of browser-based, or computer-dependent work, remain few and far between. The exhibition was envisioned by my colleague Michael Connor, artistic director for Rhizome, and is co-organized with our assistant curator of net art, Aria Dean.

Sutton: This project is self-described as “Retelling the history of net art from the 1980s through the present day.” How are the works selected and in what way do they represent a “retelling” of that history?

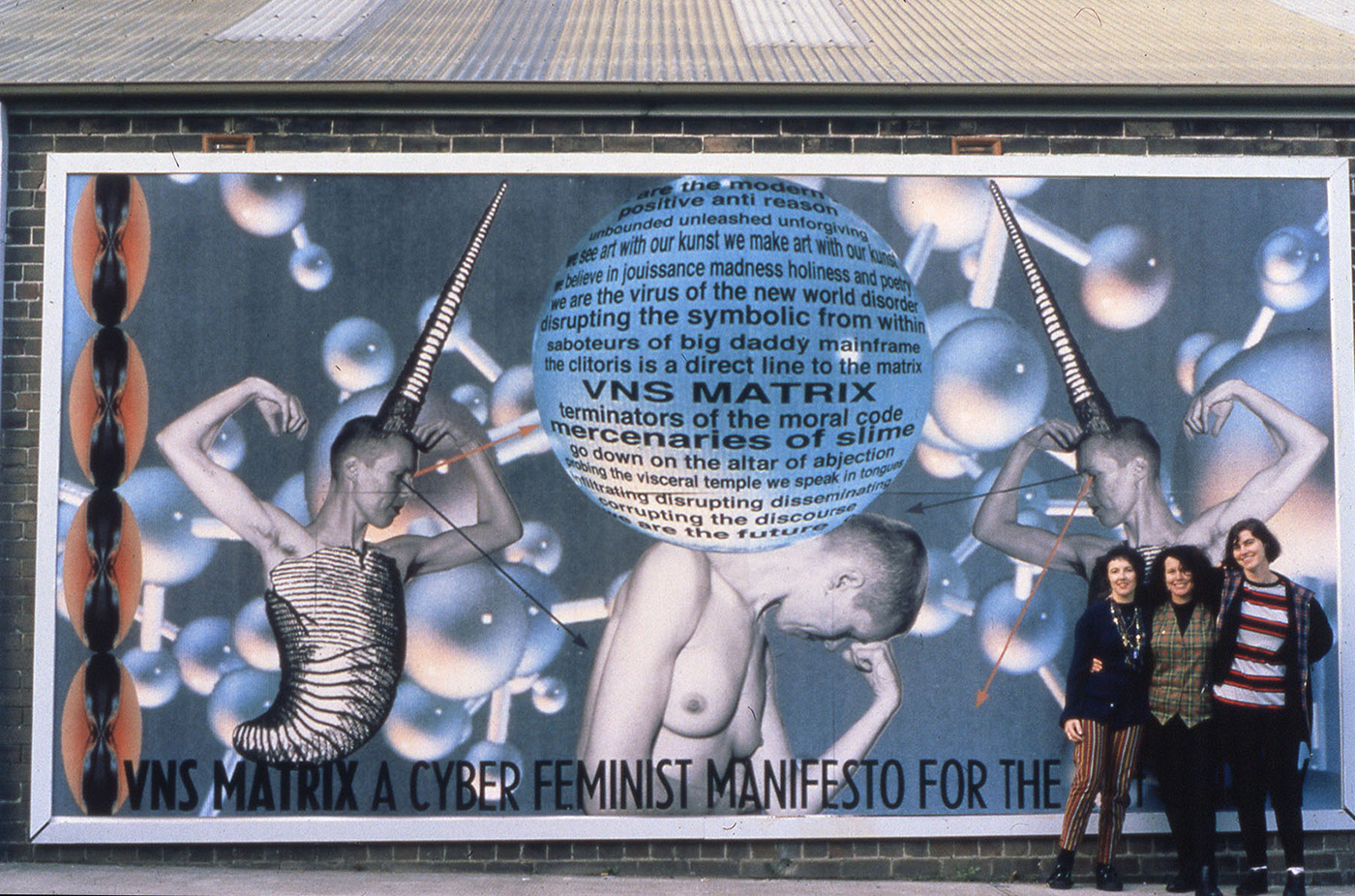

Kaplan: Overall, the exhibition is meant to be a pluralistic portrait of this thing we call “net art,” and not necessarily a canon for the form. When one talks about net art one talks about the entire internet, so we’ve selected works that express the diversity and potential of net art as a form. In keeping, we launched the exhibition not with a purely browser-based work, but rather with A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, by the Australian-based artists collective VNS Matrix (Josephine Starrs, Julianne Pierce, Francesca da Rimini, and Virginia Barratt), that was circulated by email, on listservs, on message boards, and also as a billboard and wheat-paste posters. It’s a great first work for the Anthology as it has so many elements associated with net art, such as being community-oriented, immediately remixed, and distributed in ways that were non-intuitive. It was also important to launch with a work like this because it runs counter to extant male-dominated histories of net art, new media art, and, well, contemporary art generally.

A billboard based on the manifesto shown on the side of Tin Sheds Gallery, Sydney, in 1992.

Photo: VNS Matrix.

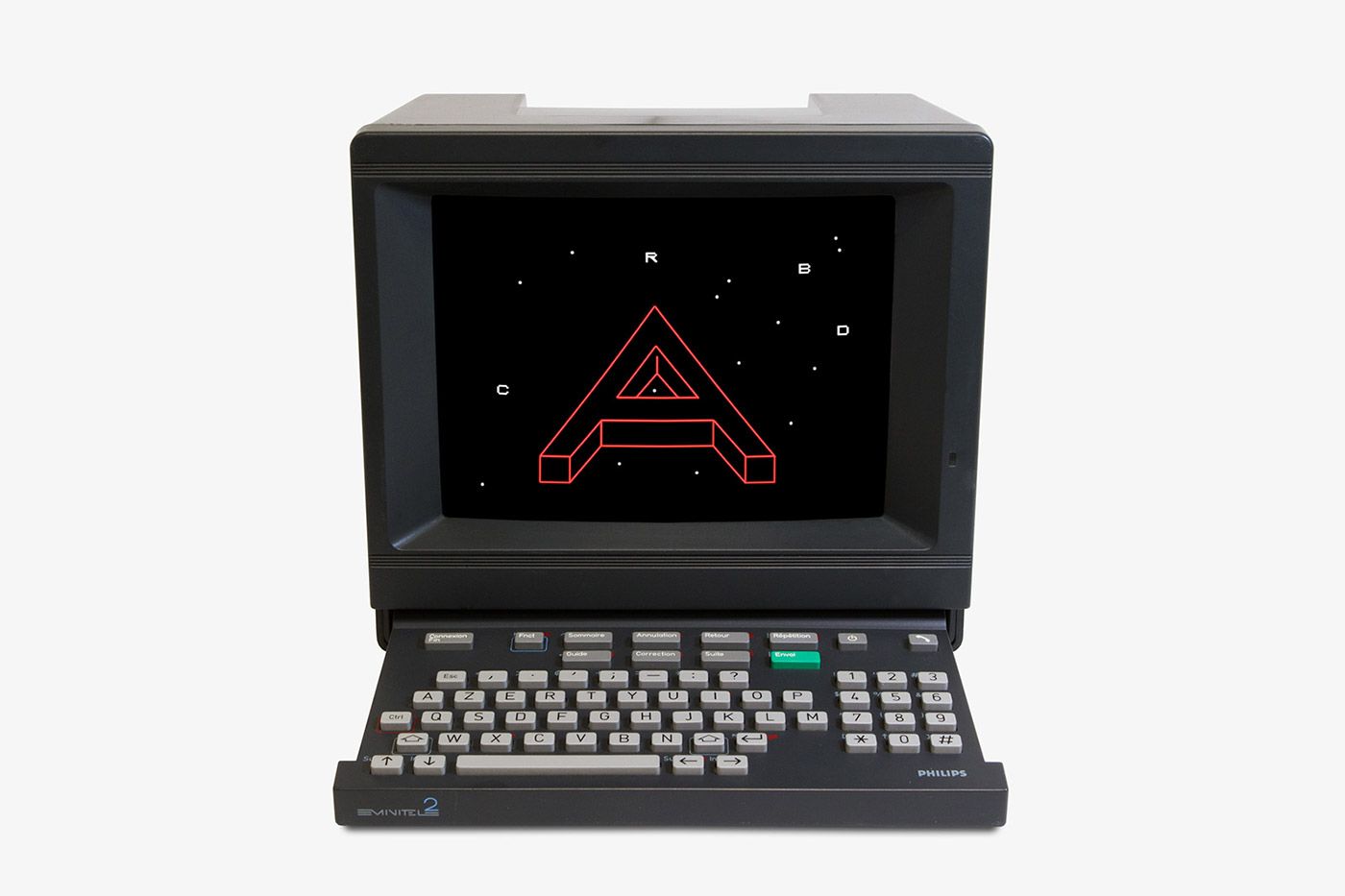

The second work selected, REABRACADABRA (1984) by Brazilian artist Eduardo Kac, challenges the common conception of what the internet is itself. In Brazil, Kac had access to a proto-internet called videotexto which was run on minitel network. This was proprietary (owned by Phillips), and really only existed in France and Brazil. To view Kac’s art, one would go to a bank, access a terminal, and link to a unique number where one could download some very beautiful early internet poetry. I’m sure very few people experienced this work in 1985 when it was created. As the network no longer exists, we exhibited the work as a video from a rigged hardware-video version that Kac has created.

Sutton: These early works seem extremely fragile due to their unique distribution and conception methods. What strategies have the digital preservation shop developed to manage these born-digital works?

Kaplan: So digital preservation has been a major concern for Rhizome since founding, and a program focus since 2008. In 2014, we hired an incredible preservation lead, Dragan Espenschied, who has transformed our efforts, but also the field itself. Today, Rhizome is seen as a hub for innovative preservation solutions.

Dragan’s big innovation was asserting that, contrary to traditional archives items, there is no such thing as a born-digital object—by which I mean a defined, static artifact that can be fully articulated by date, look, dimensions, creator, color palette, etc. Rather, Dragan argues, there is only a performance of code. Our preservation program is built around this idea of preserving performance.

Born-digital things are all about their dependencies. There’s software, there’s hardware, there’s an ensemble of them together in specific orientations. There’s variability in the object itself. A good example of this is that I could give you a floppy disc; and likely no one, no one on campus even, could perform it even if it was in pristine condition. It’s a pristine object though! So we think about performance, how code performs in a given environment. We think about variability. There’s never one computer ensemble in which people viewed a given file. Your computer could’ve been a Mac, running OSX classic, or a PC from Zeos, and a monitor from Toshiba, running Windows 3.1. That monitor could’ve been set to 640 x 480. It could’ve been set with 256 colors versus 128. These are all variabilities that can radically shift the viewing of one simple HTML website.

Sutton: Can you give an example of this approach?

Kaplan: In 2015, we presented three CD-ROM works by Theresa Duncan: Chop Suey (1995), Smarty (1996), and Zero Zero (1997). These were created for young girls, a demographic completely ignored by major game studios. Instead, she made dreamy things that weren’t Doom or Barbie: Fashion Designer, that were made to express what it’s like to be a young girl.

These were important artifacts, and entirely inaccessible to most people. To play them one needed a legacy computer and an original CD-ROM, or to download an emulator (a virtual machine on a modern computer) paired to a likely pirated ROM file. In our performance paradigm, we think emulation makes a lot of sense as it can allow access to legacy artifacts on contemporary machines. We don’t like the piracy of an artist’s work, however, or the need for a user to navigate grey market software. So with partners at University of Freiburg in Germany we’ve created a cloud-computing framework to deliver fully-functional emulators in a browser iframe.

This is how we performed these works for a mass audience—we used the Emulation-as-a-Service framework to deliver legacy computing environments to anyone with a fast internet connection, which auto-boot to the works (rights cleared, of course!), and is playable just like that.

The Duncan CD-ROMs were a prototype, and through them we’ve developed a backend system to pair legacy artifacts (like CD-ROMs) with fully aligned computing environments. This is a huge deal for presenting born digital artwork in a variety of settings.

Sutton: Emulation sounds like an ideal solution for software-based works where all the files are packaged together and available offline, but most of the services we consume online are behind proprietary networks that limit access and archiving.

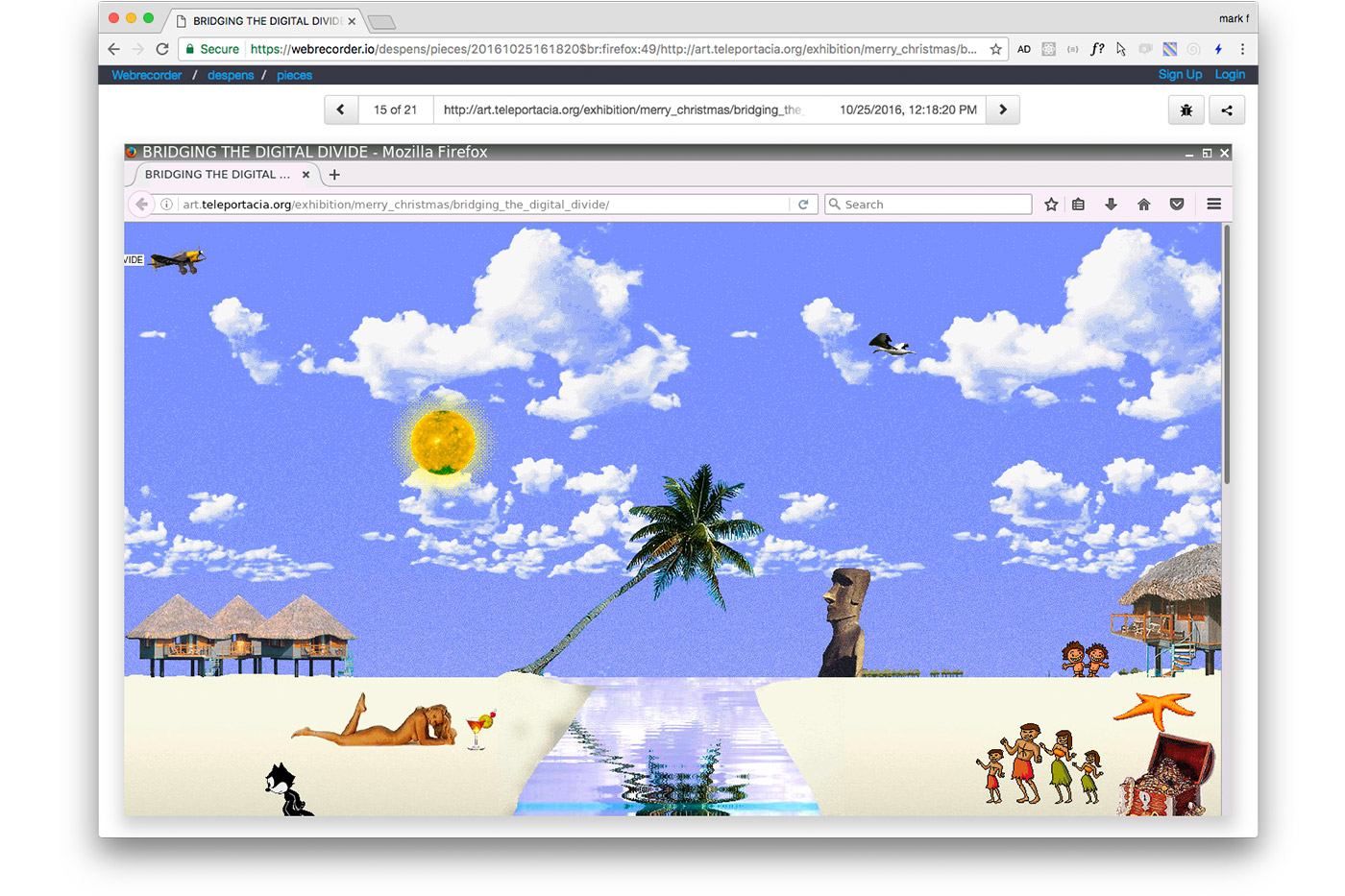

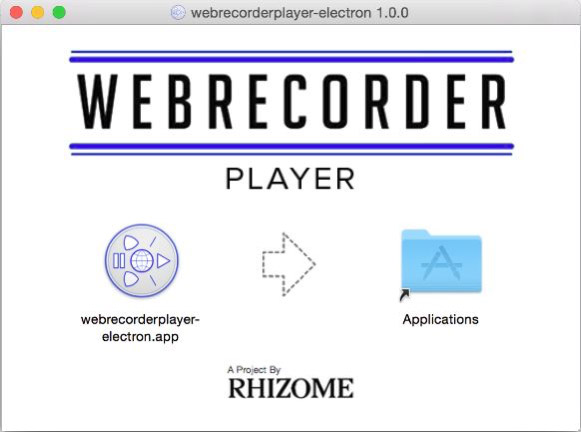

Kaplan: Yes, so emulation is great for discrete legacy files, but you’re right to say that the web, with its porous, platform-based boundaries is where so much digital culture happens today. To capture and perform this material, we’ve created a tool called Webrecorder, a project led by Dragan and Ilya Kreymer, a very visionary developer who has been at Rhizome since 2016.

For example, Facebook has something called a “newsfeed,” which presents all your friends’ and liked brands’ status updated. A lot of life happens at this page, which bears the URL, facebook.com. That singular URL is a lie. There is no facebook.com, an html page that you could just save. Rather facebook.com is a conduit to endlessly iterative software that delivers a newsfeed page to you created entirely by your actions on the platform elsewhere. Personalized, dynamic, interactive is the direction of the web, and Webrecorder was a tool we created for that future. Unlike traditional web archiving approaches that collect en masse via bots crawling the static documents of the web, Webrecorder archives as one interacts with content. We call this “symmetrical archiving,” and it is about archiving performance.

Once archived in a standard WARC file (short for Web ARChive file, an ISO standard file format for storing web archives), Webrecorder’s great trick (called pywb) is that it can fully reconstruct that file with all its interaction intact, as if it’s still a live page on Facebook infrastructure.

As the web becomes increasingly defined by the personalized view of content, tools to archive this view—whether to capture art, or discussion, or news—are essential. We’ve used Webrecorder to capture things as diverse as flash-based art from the 90s, and, with the Obama White House, the former President’s social media legacy.

Sutton: It’s great that this tool is publicly accessible and available to anyone to download and use. Was the decision to do so connected to Rhizome’s history as a community-oriented organization?

Kaplan: Definitely. We see these open-source software development projects as reflecting our non-hierarchical history and values. And the tools themselves rely heavily on values from enthusiast preservation communities—like those trying to rescue Atari games—and differ in significant ways from the professional preservation world.

That said, there is an important role for cultural organizations to play in digital and internet memory. As is, there’s a lot of apathy in the marketplace to protecting what users create. The maintaining access question is not abstract to us—it’s tied to art that we believe in, and communities that we want to support and that we value. Folks will express themselves via the platforms that enable their expression. Those platforms may wither, and disappear. It’s not malice, but the concerns of user and platform don’t necessarily align. As an internet art organization, we try to speak and say that the things you created matter. It’s an uphill battle.

Further Reading

Net Art Anthology: anthology.rhizome.org

Dragan Espenschied, “Big Data, Little Narration”: http://rhizome.org/editorial/2014/oct/22/big-data-little-narration/

Olia Lialina, “Rich User Experience, UX and Desktopization of War”: http://contemporary-home-computing.org/RUE/

Michael Connor, “What’s Postinternet got to do with net art”: http://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/nov/01/postinternet/

Aria Dean, “Rich Meme, Poor Meme”: http://reallifemag.com/poor-meme-rich-meme/

Main image

Screenshot of Webrecorder capturing “Bridging the Digital Divide”

in Merry Christmas: Applet Art from Bora Bora (2006) by Olia Lialina.