Video’s New Normal

The Logic of Pipilotti Rist’s “Image Errors”

Internationally recognized, Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962) is often linked to the first generation of visual artists who established the critical benchmarks for the inclusion of time-based media as a collection category within museums and galleries in the United States and Europe. However, unlike Dara Birnbaum, Joan Jonas, and Martha Rosler for example, Rist did not pick up a video camera as a means of documenting or recording movement, sound, and actions alongside the use of photography or film in a studio-based practice.

For this slightly earlier group of artists— importantly, primarily women—the turn toward video signaled a transgressive disruption of the medium-specific language of sculpture and painting which was often defined by the work of male artists. This was also a moment in the late 1970s when the term “video” was understood as a technical amalgam, a medium comprised of magnetic tape, video playback decks, and their related vocabularies and editing conventions (freeze-frame, stills, fast forward, and so on). The feminist strategy within Rist’s work, therefore, is not limited to the fact that the artist aims the fixed camera on the biologically female body; it also extends to how she overturns the mechanisms of recording technology and the narratives around mastery and control. Moreover, the popularity of Rist’s thirty-year career survey, Pixel Forest at the New Museum last year, underscores the ways that radical feminist video has become the new institutional norm.1

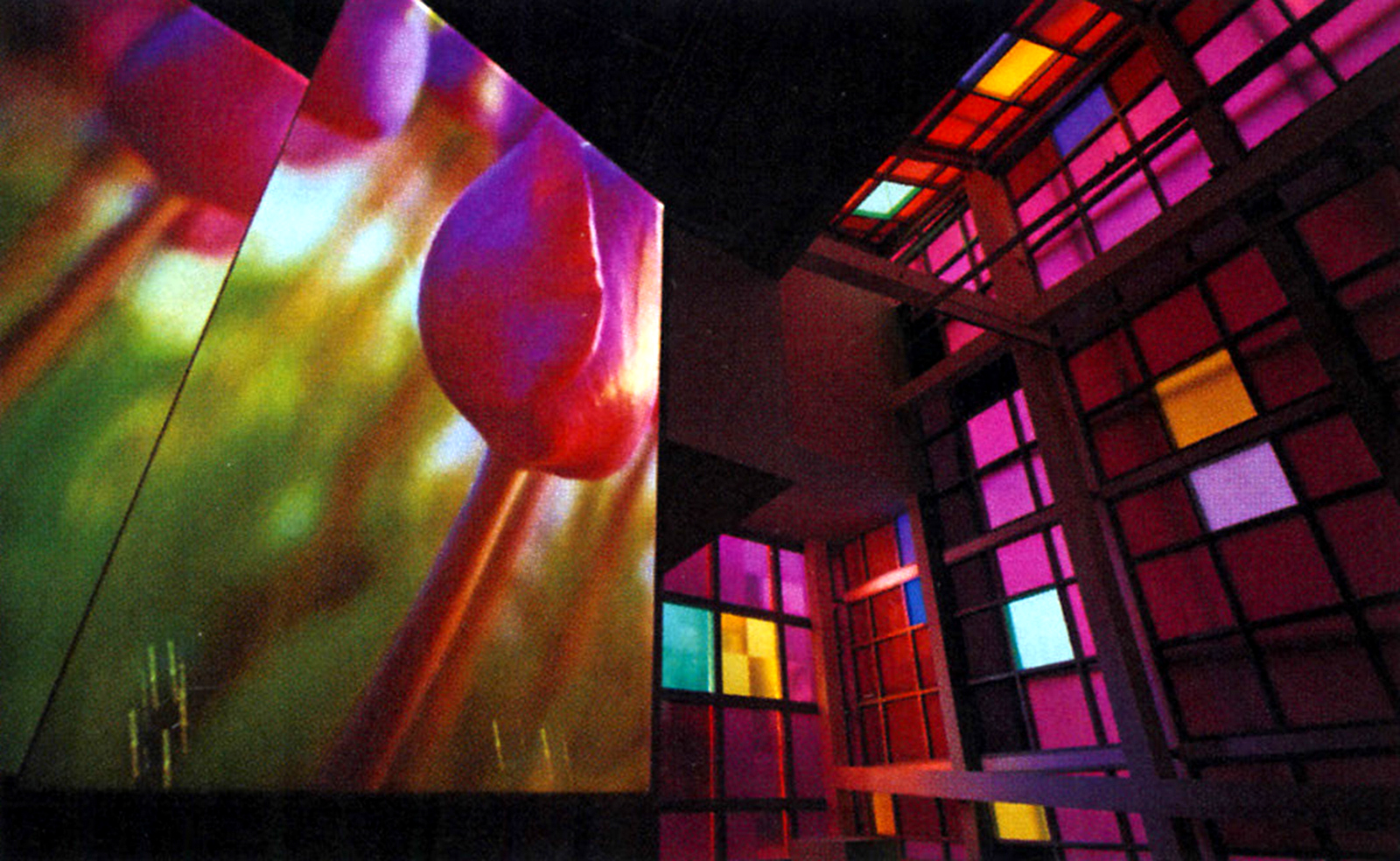

In contrast to her American and European counterparts, Rist studied at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and later graduated from the Basel School of Design in 1988 with a fine art degree specializing in video—a clear indication of the institutional acceptance of this nascent form. In fact, by the 1990s many art departments and art schools throughout North America and Europe would begin to introduce formal degree programs in video ushering in a new generation of artists trained specifically in the principles of video technology and what I would posit as its corollary: the logic of video. Within the trajectory of Rist’s well-documented body of work, we can also measure the institutional shift not only from analogue to digital, but also the move from single channel monitor work toward expansive projections which are scaled to fill a room, or a building façade.

The Software Effect

One result of no longer having to advocate for the legitimacy of video as a form is that we get to concentrate on complexities of the works’ themselves. To this end, distinct from those artists whose durational works remain in dialogue with the grammar of lens-based images (namely photography and film), I would suggest that Rist’s videos begin to outline the difficulties of new media by taking on the peculiar behaviors we associate not with cameras, but with software. The impact of such a shift is not limited to recalibrating Rist’s own art history, but the broader field of moving image installation can be reinterpreted through the specific vocabulary introduced by the spread of contemporary digital culture. Therefore, we begin to speak of interfaces rather than mediums; connectivity over reception; iteration instead of originality; a composite, in lieu of an assemblage; and compression—not abstraction—becomes the dominant process of encoding information using fewer bits. And as digital media theorist Wendy Hui Kyong Chun has argued in her pivotal study Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (2011), “Software challenges our understanding not only because it works invisibly, but also because it is fundamentally ephemeral—it cannot be reduced to program data stored on a hard disk.”2 More specifically, I want to suggest that Rist’s turn from single-channel to architecturally scaled projections and installations points to the recombinant nature of the very structures that both produce and circulate digital images.

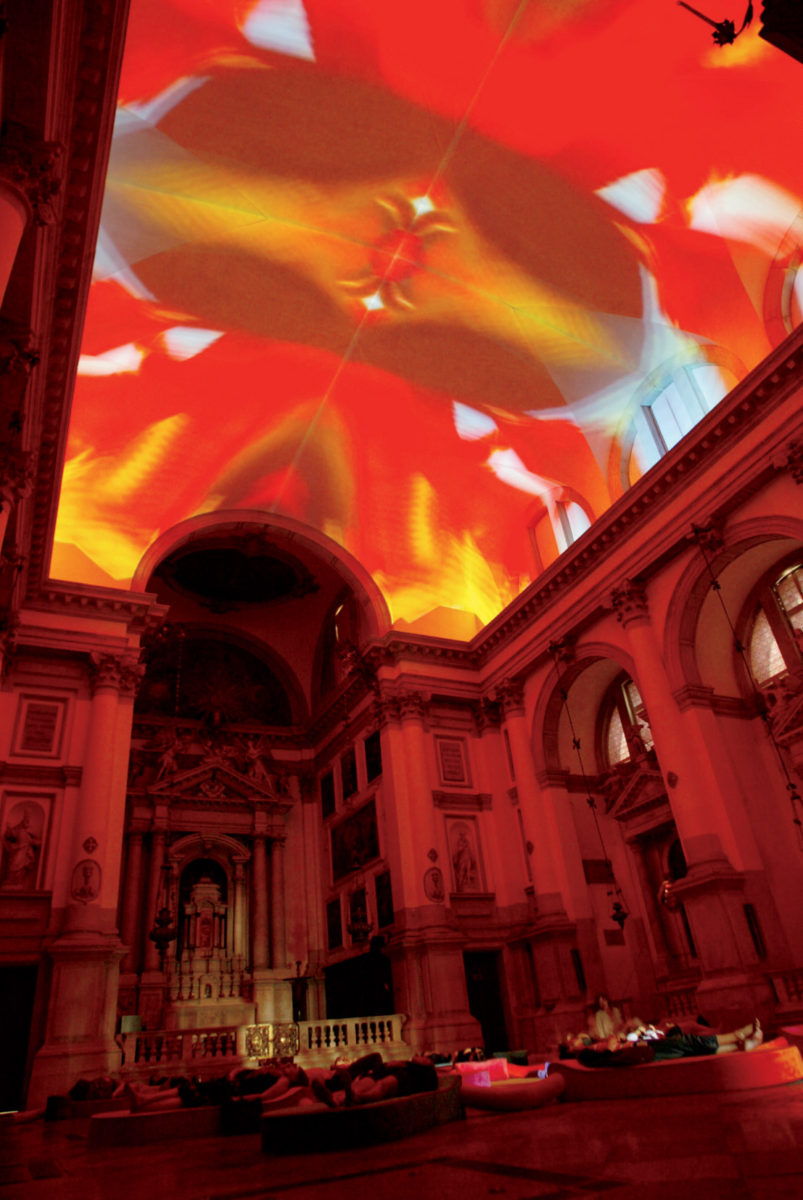

Rist’s often salacious video content—swelling flesh, pulsing orifices, and flashes of taboo subject matter including representations of intercourse, afterbirth, and menstrual blood, for example—have been the central focus of the analysis that has grown in direct proportion to her copious exhibition record. This hypnotic image content is equally matched by the luxurious amount of space often afforded her projections which have been scaled to fit the ornate vaulted ceiling of the baroque church of San Stae located on the Grand Canal in Venice Italy are equally at home filling expanses of white space and glass in contemporary art museums.

Pipilotti Rist, The Tender Room, 2011

Audio video installation

Installation view, Wexner Center for the Arts, The Tender Room, Columbus OH, 2011

Photo: Kevin Fitszimons, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

The spectacular effects of her cacophonous installations often divert the viewer from her work’s technical precision, which are calculated with her longtime collaborators Anders Guggisberg (sound recording) and Käthe Walser (design and installation). Reflecting a key aspect of VoCA’s multifaceted mission—examining material issues endemic to contemporary art—it is precisely these types of technical image manipulations, errors, and accidents exploited by Rist which present an interesting quandary for conservation and art history. How do we preserve such image degradation in a digital age that is conditioned by the mandate for increasing image refinement, clarity, and stability?

Image Errors

In the late 1980s, video errors such as smearing and dropouts were key to the analogue qualities of working with magnetic tape. In Sexy Sad I (1987), one of Rist’s earliest works, the artist makes ample use of “color smearing,” the phenomenon that becomes manifest after an editing cut when a disturbance in the image moves slowly over the screen until the next image appears. Sexy Sad I intersperses footage of a naked male body from the neck down cavorting in sepia-toned woodlands with the garish, hyper saturated bars of early video graphics. Both the movements of the body and the soundtrack of the Beatles song “Sexy Sadie” are distorted, becoming stretched to the point of warping.

This is not merely a metaphorical description of the activities on screen or on the soundtrack, but a physical symptom, an error resulting from linear video editing. These sequences are made during the editing process when a new recording is laid over an existing one. The old information is never fully erased, and residue from the previously recorded signal is displayed as a semitransparent color smearing. Likewise, remnants from a preexisting audio track may also be subject to these types of errors. It becomes permanently recorded on the tape as image content.

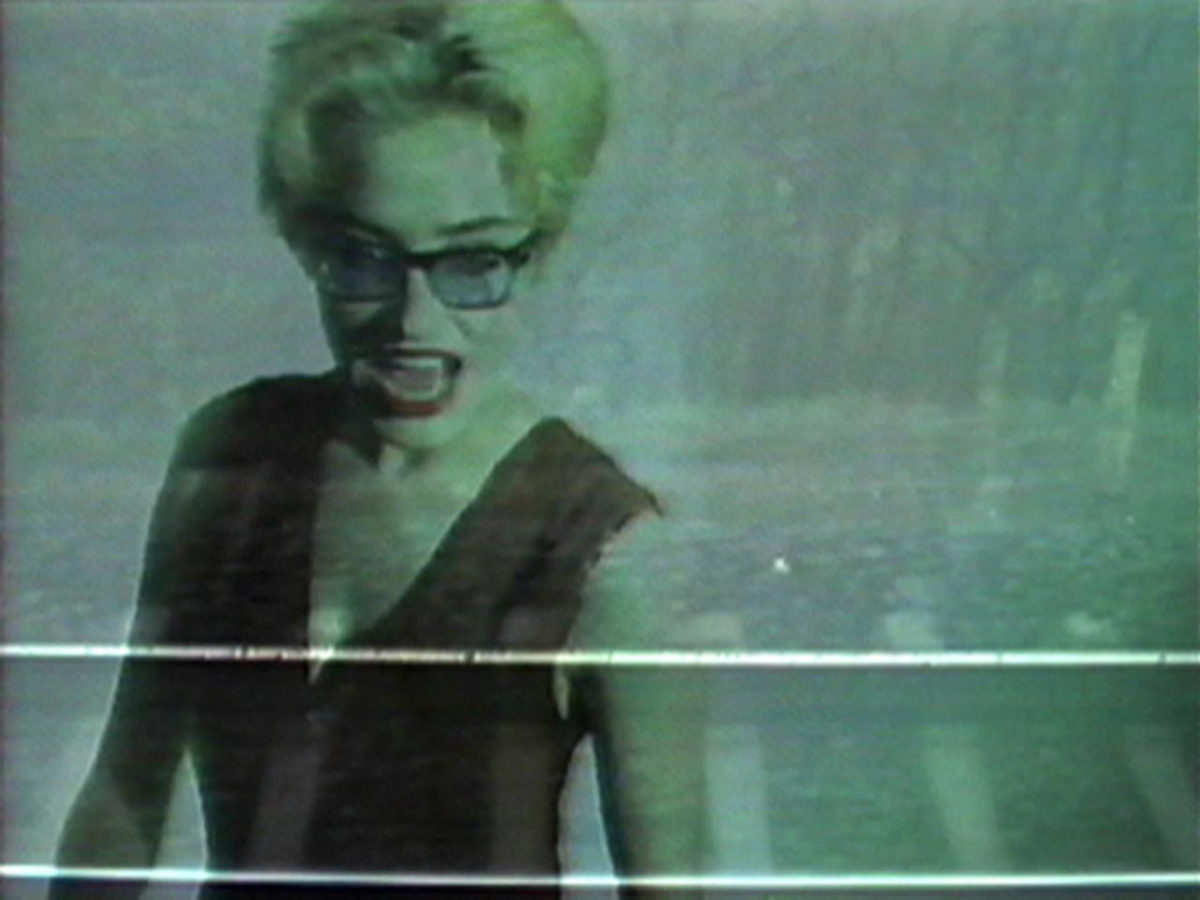

These material and technical aspects of Rist’s work do not negate the established reading of her videos as a reversal of the gendered hierarchies of power and control. However, it does challenge what I would identify as an overemphasis on the screen and screen-based mediation as the dominant frame of reference in the discourse on moving images. Instead of screens, the video is clearly and literally reliant on material, accretive processes—the accumulation and the erasure of information or data—reminding us of video’s fundamental role as a medium for storage rather than transmission. And, contrary to the way it has been historicized within visual art, Rist’s works demonstrate how video is distinct from television (which simply transmits content that was originally recorded using a video camera) and completely separate from the invention of photography. That does not mean transmission, and the breakdown of transmission more specifically, is not of interest to Rist, who has regularly exploited the incompatibility among international television standards (PAL, SECAM, NTSC).3 This technique is put on full display in the video You Called Me Jacky (1990), in which a PAL tape becomes distorted when it is played back in a multi-standard player set to NTSC. This results in the vertical compression of the image (a bespectacled Rist), causing it to be broken up into narrow horizontal stripes.

And that’s all within the operations of recording.

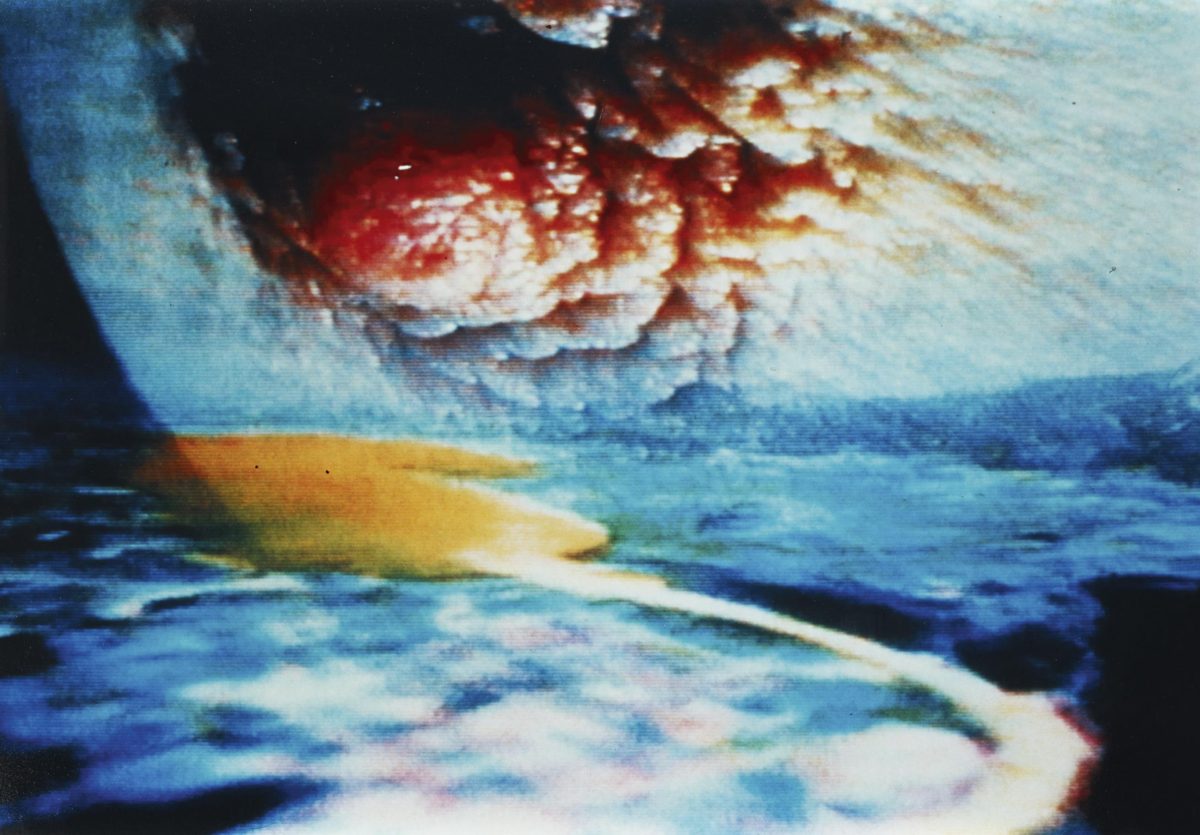

During installation and playback on monitors installed in museums and gallery spaces, Rist’s single-channel videos precisely reveal the subjective process of achieving desired color and saturation levels, which shift and need constant recalibration not only from monitor to monitor, but also every time a video is played. Rist makes ample use of image errors, including interference and dropouts that are produced by consciously ignoring the “true values” of hue control and video signal regulation. This is expertly deployed in the moiré images that flash throughout Pickelporno (Pimple Porno) (1992), for example—a video that Rist has described as an “attempt to trace a journey just in front of and just behind our eyelids.”4

The fallacy of control with regard to chromatic calibration has given rise to the ironic interpretation of the acronym NTSC as “Never the Same Color”—reminding us that there is no precise reference for color control.5 It is these types of formal discrepancies that emphasize the social issues inherent to working with technologies of image reproduction and transmission that have been a consistent through-line in Rist’s work, underscoring her pressing point that “reality is more saturated than we can ever create with an electronic device.”6

Because of the prominence of these processes and material manipulations in Rist’s early work, historical allusions are often drawn to Nam June Paik, whose deft handling of video’s hardware through nimble bricolage and conceptual rigor with the medium’s memory and televisual feedback functions became synonymous with video as a critical art form from its inception in the 1960s.7 However, by the late 1980s, when Rist started exhibiting her work, video’s manipulation and distortions could no longer be read simply as metaphors for broadcast television broadly framed.8 Recounting how the visual stutter she uses in I’m Not the Girl Who Misses Much functions, for instance, Rist has noted:

I call it an ‘exorcistic’ video, because of the contradiction between what the character is saying…in the sense of lack and the way that she moves. She looks trapped, condemned to repeat, which contradicts what she says. She moves in a way that we sometimes feel, as if we were puppets played by others but we have to keep the balance between an imagined freedom and being the victim of constraints.9

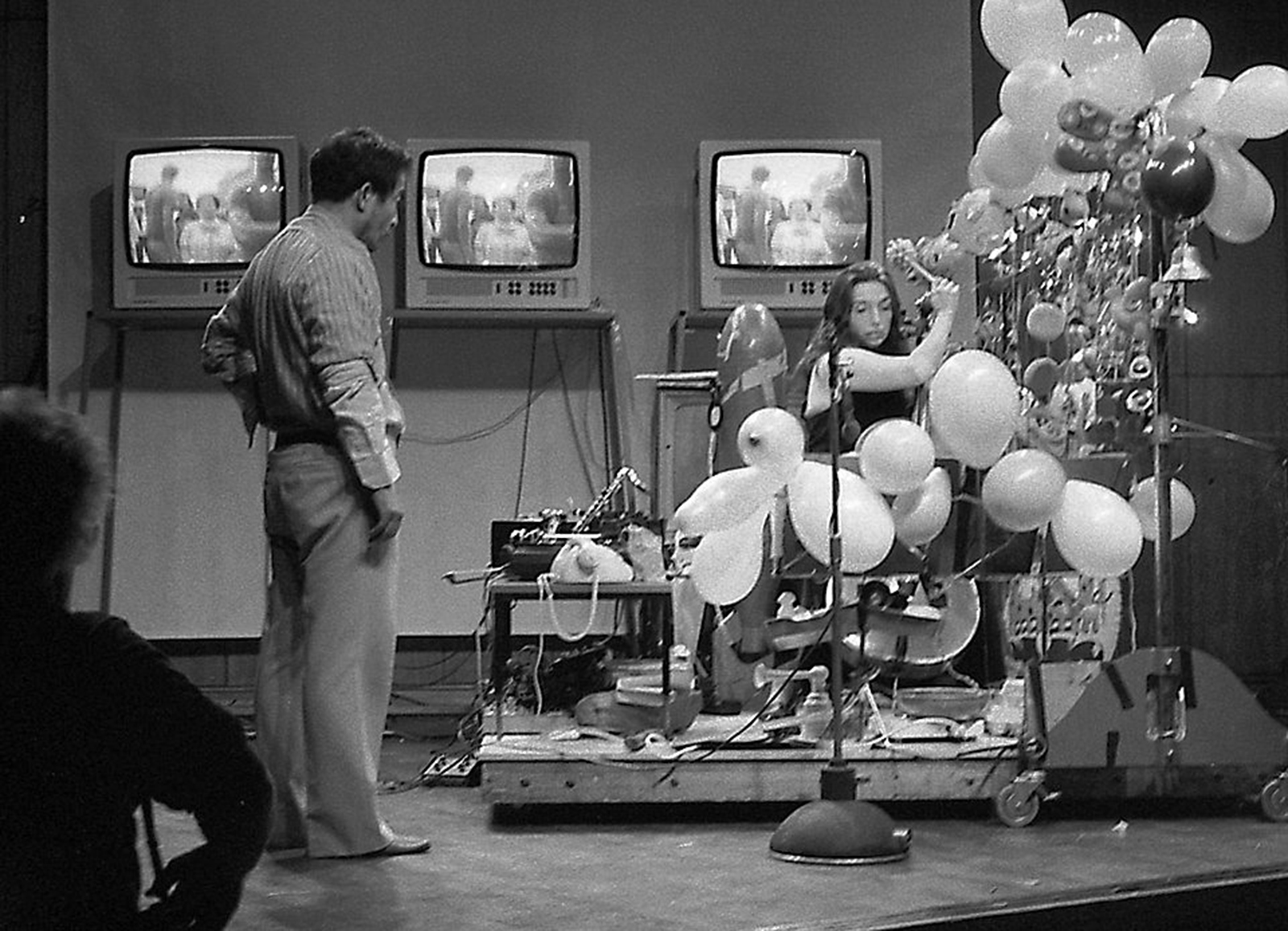

In this context, Rist’s critical use of feedback loops and her distortion of signal-to-noise ratios would take on a different type of radical politics—centered on the mediated female body. In this manner, perhaps artist Charlotte Moorman, who as the prolific organizer of intermedia festivals between 1965 and 1980 did the most to broaden the reach of avant-garde mixed-media experiments, is a more fitting point of comparison than her frequent collaborator Nam June Paik.10

Charlotte Moorman with Nam June Paik, 1980 Performance of John Cage’s 26’1.1499” for a String Player Photo

Reception Theory

Challenging video’s epistemological connections to the documentary function of photography and its positioning as an unbiased recording device whose content is admissible in a court of law, Rist underscores the important fact that video is not a neutral technology. The feminist strategy within Rist’s work also extends to how she overturns the mechanisms of technology to reveal its social conditioning, reflecting the complex markers of gender and race. As Rist has cogently remarked, “Because everyone is afraid that skin will look too red or blue or greenish, the machines have these built-in standards to reduce color so people—white people, mainly—look healthy.”11 She makes the salient point that applies to many conventions and assumptions surrounding media and subjectivity: “If film had developed first in Africa, the standards would be completely different.”12 “If you play your video too fast or slow, the built-in, time-based corrector compensates by filling in the data it needs,” Rist has noted. “You also have limiters for brightness. To change the limiters, you have to ignore or destroy all the given standards.”13 These references are not just technical arguments about video’s formal traits, but issues of control and correction that have profound social ramifications.

Counter to the leveling effect associated with Flickr or Tumblr, Rist is not aggregating images. However, even her earliest image streams and installations point to the contradictions of our current neoliberal economic order that conditions the reception of via proprietary software applications and requires users to exchange private information in order to participate in this public forum. Rist’s installations reflect and refract back to us the utopian promises of freedom and control associated with the advent of instant communication regardless of geographic locale, which continue to dominate and drown out the inherent problems of access and inequality (economic and racial) that have become native to the internet and social media platforms. If the centralized model of broadcast television helped to establish many of early video’s enduring aesthetic concerns, Rist’s digital environments show us how these network issues continue to prevail in contemporary art.

1 Pipilotti Rist Pixel Forest was on view at the New Museum October 26, 2016—January 15, 2017. This essay draws from my contribution to the accompanying catalogue. See Gloria Sutton, “Reception Theory: Difficulty, Dropouts, and Interference in the Moving Images of Pipilotti Rist,” Pipilotti Rist Pixel Forest (New York and London: Phaidon Press): 95-133.

2 A Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 3.

3 NTSC is the abbreviation of “National Television System Committee,” which became the television standard in the United States in 1953 and remained the main standard in the US, Japan, and other countries until 2009. In 1967, PAL, or “Phase Altering Line,” was introduced in Germany as an enhancement of the American NTSC, and SECAM, or “Séquentielle Couleur Avec Mémoire” [Sequential Color With Memory], became the television standard for France. Unlike PAL or NTSC, SECAM is exclusively frequency modulated. See Joanna Phillips and Agathe Jarczyk, “Glossary of Video Terminology,” Kompendium der Bildstorungen beim Analogen Video (Bern: Swiss Institute for Art Research, Hochschule der Künste Bern, 2012), 228–29, 233.

4 Rist, interviewed by Richard Julin, in Pipilotti Rist: Congratulations!, eds. Richard Julin and Tessa Praun, trans. Matthew Partridge (Baden: Lars Müller; Stockholm: Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall, 2007), 69.

5 Joanna Phillips and Agathe Jarczyk, “Glossary of Video Terminology,” 229.

6 Pipilotti Rist, interviewed by Linda Yablonsky, in Wishing for Synchronicity: Works by Pipilotti Rist (Houston, TX: Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2009), 46. The exhibition was on view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston from October 14, 2006 to January 14, 2007.

7 Rist herself makes this allusion by including the preface to Paik’s 1993 essay, “Nam June Paik: Jardin Illuminé,” in her first English-language monograph, see Pipilotti Rist, eds. Peggy Phelan, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Elisabeth Bronfen (London: Phaidon, 2001), 110–13.

8As early as the 1970s even, as visual artists engaged in projects designed specifically for non-art venues, key shifts occurred in the development of communication technologies and platforms. In addition to the rapid growth of a consumer electronics industry, this was also the very moment when the consolidation of cable television in the United States represented a viable challenge to the dominance of the commercial practices of video and broadcast technology—what is customarily referred to as “network programming.” Cable television’s inevitable commercialization and depoliticizing in the 1970s were not part of a foregone conclusion. As art historian David Joselit remarked in Feedback: Television Against Democracy, his careful apparatus-focused analysis of how television operated at the nexus of politics and representation in the United States, “Television existed as a technology before it was clear how it might be marketed as a product.” David Joselit, Feedback: Television Against Democracy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 15.

9 Rist, interviewed by Yablonsky, in Wishing for Synchronicity, 45.

10 For a detailed account of Moorman’s work and impact, see Joan Rothfuss, Topless Cellist: The Improbable Life of Charlotte Moorman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014).

11 Rist, interviewed by Yablonsky, in Wishing for Synchronicity, 46.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid, 47.