Transmissions

Traces Of The Past In JODI’s Variable Art

A core tenet of the practice of art history has been that objects are its fundamental units of analysis. These artifacts are preserved within museum collections for their valuable information about our past. Recently different kinds of things have begun entering museum collections: digital artworks, whose distinctive features challenge these traditional conceptions. Notions such as the participation of users and procedures of action redefine artworks as not solely static artifacts.1 Approaching them as unchanging objects is misleading and restricts our comprehension of what they truly are.

In an attempt to provide a critical understanding of these media artworks, it is important to take into account their variable character. The term “variability” in relation to new media was explained by Lev Manovich as follows: “New media objects are not something fixed once and for all, but something that can exist in different, potentially infinite versions.”2 Depending on data input and interaction, these works of art are not finite, but constantly in motion. They can move from the virtual towards the physical, adapt to new technological environments, or be re-interpreted by recipients. For a better understanding of these artworks we need to understand them as being in process. It is within their biography that we can see how they develop over time.

This article deals with a specific example of such a biography by examining the variable artworks of JODI, one of the most influential artist groups working on the web and important pioneers in the artistic manipulation of videogames. In particular I will look at their experiments on the ZX Spectrum, among the first mainstream British home computers (similar in significance as the Commodore 64 in the USA). These artworks came forth out of JODI’s interest in old computer languages that are in danger of being forgotten, as is the case with BASIC, a programming language that was used for the ZX Spectrum. How can we remember not only the language, but also the culture around it?

In the exhibition JODI: Variable Art for the ZX Spectrum (2016), held at Dundee Contemporary Arts from August 1–28, 2016, JODI’s experiments on the ZX Spectrum were brought together for the first time. In the show, JODI presented how their artwork can be adapted to new technological environments and transferred to different media—from videogames and websites to user instructions, videos and maps, with each version showing a different perspective on the past. Often exhibitions only show a single version of an artwork, a snapshot from its life. This exhibition showed an overview of the life trajectory of the artwork in all its different variations, presented beside one another, so viewers could examine and compare them. The artwork’s final form, meaning, and significance thus remain open for debate.

In 1984, the iconic videogame Jet Set Willy was released for the British home computer the Sinclair ZX Spectrum. The game was part of a broader culture of teenage hobby programmers, a “Do It Yourself” subculture still known to many software developers today. When JODI started making their work Jet Set Willy Variations in 2002, the ZX Spectrum computer was already obsolete and its program language BASIC was in danger of being forgotten. As homage to the programming language and the culture around it, JODI decided to modify the game Jet Set Willy. Within game culture modifications are a widespread phenomenon. The earliest computer games were collaborative texts, (re)produced and (re)distributed by their users. Since then communities encourage each other to enhance and tweak new (gaming) technologies.

The modification of Jet Set Willy was also a way to revive the (almost obsolete) code, as well as the cultural context of game development and its DIY mentality. Digital products often grow and evolve, because other users and programmers add or modify existing programs. For some artists, including JODI, the vision that artworks need to be shared, circulated, and modified is an essential element within an art practice and also in artistic thinking about the future of individual artworks. For archivists the modification of games is a well-known preservation strategy to keep games accessible and playable after hardware platforms including consoles become obsolete. However, JODI went a step further than most archivists would go.

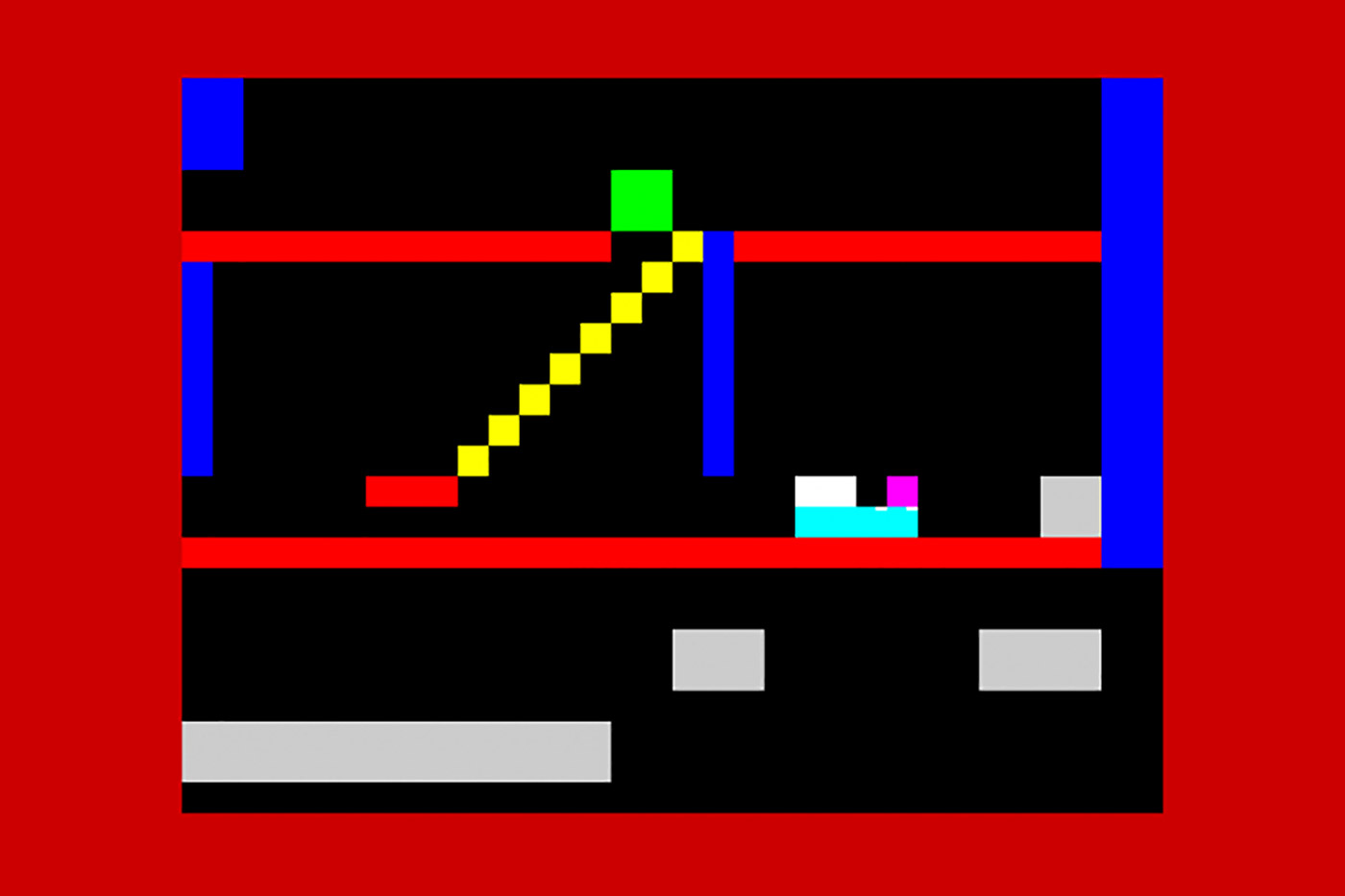

For instance, by modifying the game visuals, JODI changed the resolution of the game, making the avatar into a single pixel (a square) that moves around in a world that consists of lines, forms and colors. Although the modification is very simple in digital terms (lowering the resolution), taking out the representative elements drastically changes how we experience the game. At first sight, this could lead to the conclusion that JODI’s re-interpretation of the game gives fewer references to the past, unless, that is, one becomes more aware of also the other Jet Set Willy Variations. There is a variation that shows the story of the game, another how copyright was protected and there is also a version that focuses explicitly on the “sprites” in the game.3 Each Jet Set Willy Variation draws our attention to fundamentals of the game that have become obsolete.

JODI’s work is characterized by a deconstructive aesthetic. This approach, based on the ideas of French philosopher Jacques Derrida, dismantles the system into different elements and analyzes the relationships between them. As such we get a better understanding of how the whole is constructed and, instead of jumping to conclusions, are able to question the meanings perceived at first sight. In Jet Set Willy Variations we see how JODI disassembles game culture into elements that constitute its foundation, but that are less obvious and in need of recovering, like the resolution, the sprites, the story, and copyrights. It zooms in on these elements that are in danger of being forgotten.

How should one display the artwork Jet Set Willy Variations? The artwork is variable in that it continuously transforms and survives by adapting to new contexts and environments. Consequently, over time it has been exhibited in various ways. The aim for the exhibition JODI: Variable Art for the ZX Spectrum (2016) was to present the artwork’s life trajectory and as such it presented the artwork in all of its different forms. This was, among others, inspired by the work of researcher and curator Annet Dekker, who argues that for the presentation and preservation of these artworks it is essential to “assemble traces.” Over time, certain elements of the artwork become obsolete, others stay the same or mutate into something else. All different variations and versions are traces of the past and as such can be inserted into art history.4 To find a profound understanding of the artwork Jet Set Willy Variations, the exhibition did exactly that: it included all the different versions, which brought into view how the artwork had evolved into multiple translations and, what Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin termed as “remediations” (a representation of one medium in another medium).5

Left: JODI, Jet Set Willy Variations .SNA (JSW011), 2002

ZX Spectrum software as 48K snapshots, ZX Spectrum emulator and duplicable hardware

Shown: iMac 21,5” (late 2012) with OS X Yosemite Version 10.10.5

Right: JODI, Jet Set Willy Variations .TAP (JSW011), 2002

ZX Spectrum computer software on audiocassette and duplicable hardware

Shown: ZX Spectrum computer, audiocassette player, Sony KV-1400 14″ TV with color, sound and RF

Behind: JODI, Jet Set Willy Variations .MAP (JSW011), 2002 – present

Duplicable print (free download at jetsetwillyvariations.com), dimensions variable

Installation detail of JODI: Variable Art for the ZX Spectrum (2016), Dundee Contemporary Arts (Visual Research Centre)

Photo: Kathryn Rattra, courtesy NEoN Digital Arts

JODI gained access to the code of the game Jet Set Willy through an emulator (a program that enables new computers to mimic older ones in order to run old software). JODI then modified the code, which resulted in the artwork Jet Set Willy Variations. They recorded this on an audiocassette, which made it possible to play the artwork on the original ZX Spectrum. In the exhibition both versions of the work were presented. In the image above we see on the left the emulated version and on the right the artwork on the ZX Spectrum. The artwork was exhibited similarly to how other media art works were displayed in the exhibition Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice (organized in 2004 by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York). The 2004 exhibition was designed to gain insights into how artworks transform after being emulated. Eight important media artworks were shown in pairs: The “original” versions next to how they could look like in the future after being emulated. Ironically, Jet Set Willy Variations did not originate on the ZX Spectrum; rather, it was created from the emulator. Re-interpretations can question notions of an original and of authenticity. Having many versions, prototypes, unofficial releases, and altered editions, these artefacts do not fit in a linear passage of time.

JODI, Jet Set Willy Variations .MOV (Sprites), 2002–present

Gameplay, duplicable videos, color, sound

Courtesy of the artists

Alongside the computers, the artwork was shown in various forms of documentation. JODI does not consider the additional documentation as a substitute for the digital works, but as part of their variable nature. At most we could speak of another phase within their artworks that are not finished at any point, but evolve in many directions over time. The exhibition presented, among others, videos that record the artworks being played (see above). The ZX Spectrum was a computer that needed to be connected to a television and to stay as close as possible to the “original” appearance; these videos were presented on televisions as well, along with maps of the game. In the game Jet Set Willy the protagonist Willy has to clean up his mansion that he bought from the wealth he obtained during his previous adventures. As the game was quite complicated, a map of the 61-room mansion was developed as a walkthrough. JODI adapted this form to make a new version of their artwork Jet Set Willy Variations.

JODI, All Wrongs Reversed©1982, 2004

Video, 45’50”, color, sound

Installation detail of JODI: Variable Art for the ZX Spectrum (2016)

Dundee Contemporary Arts (Visual Research Centre)

Photo: Kathryn Rattra, courtesy NEoN Digital Arts

The exhibition JODI: Variable Art for the ZX Spectrum (2016) spanned two galleries. Where one room was dedicated to the artwork Jet Set Willy Variations (2002), the other room was dedicated to its program language BASIC. A central position was given to the artwork All Wrongs Reversed©1982 (2004). In this video we see the registration of JODI programming simple graphics in BASIC. Only the screen is recorded, which puts a focus on the programming process over the animated graphics. In current computers this process rarely comes to the surface, but this language is essential for how these images function and how they act. It’s a trademark in JODI’s work to reveal the code, including the “wrong” code, showing the dysfunction of the machine as a comment on the relationship we have with them.

Though All Wrongs Reversed (2004) is not so much a reference to “wrong” code, it is the former term of what is now known as “copyleft,” a form of licensing that offers people the right to freely distribute copies and modified versions of a work. Typically copyright laws are used to prohibit reproductions, adaptations or distributing copies. Artworks in the digital realm are dependent on co-creation and are deeply embedded in shared practices among communities. As such, these artworks ask for an alternative copyright system.

JODI, Programs written in BASIC©1984, 2003

Type-in program, instruction sets in BASIC

Photo: Kathryn Rattra, courtesy NEoN Digital Arts

The artwork All Wrongs Reversed©1982 (2004) is more or less a video recording of the work Programs written in BASIC©1982 (2003), a version in which co-creation lies at the heart of the artwork. The work consists of a programming manual for making simple graphics for the ZX Spectrum, inviting audiences to modify ten programs written in BASIC. Here the audience is not playing a game, they do not passively look at computer graphics, but, in this case, they write simple graphics in BASIC themselves. In the exhibition it was possible to work on an emulator as well as on the ZX Spectrum itself.

The action of the participants complement JODI’s artworks, which can be seen as a reference to the history of gaming (the Do It Yourself subculture of programming and modifying games). On the other hand it is also set within art history in the tradition of the Fluxus art movement. Fluxus artworks often take the form of scores that the audience can execute, manipulate and re-interpret. In a similar way this artwork takes the form of an instruction, but in electronic space. The artists are helping audiences to write a program, in other words it provides a guide for “how to instruct the computer.” The participants, and the computer—along with chance—will continuously influence the final outcome of the artwork, creating different versions that are not identical. As Fluxus artists proposed, art should not be restricted to being a static object, but can be something that happens and transforms over time.

What insight can the exhibition JODI: Variable Art for the ZX Spectrum give us about the life trajectory of the artworks on display? As this case study tries to illustrate, first of all, there are many factors involved that influence how these software-based artworks evolve. Although the problem is probably further complicated, it does illustrate how the digital nature of these artworks are in need of more precise description.

While BASIC language and the use of it in 1980s game cultures starts to vanish, we can still get a hint of what it was like by looking at JODI’s artworks. Detached from the original context, artifacts can only show us a fragment of the past and cannot be anything other than an interpretation recalled in a particular context, time, and place. The artwork Jet Set Willy Variations reflects on how this process unfolds and instead of zooming in on a single meaning it emphasizes the various legacies of an artifact, each telling their own version of the past that can be examined and compared.

In the case of collecting games (as well as software-based artworks), building context by adding contextual materials to collections is very important to create understanding for future users. JODI’s work set out to question the boundary between an artwork and its documentation. Over time, new versions and variations are added to the artwork, without specifying the distinction between what is documentation or the artwork. Instead of a fixed object, this artwork contains a collection of variations and versions, or in other words, a web of happenings. Although artifacts can never tell the full story, digital artifacts could give historians access to data that can recover processes and reveal patterns that were invisible before. Like biological time, this will reveal unbroken events that can evolve in several directions. As long as digital artifacts will reproduce, they will stay alive. Yet the question remains: how many versions of the past will be collected and preserved (by museums or other institutions) so that their traces can be uncovered?

1 A procedure is a section of a computer program that carries out some well-defined operations on data specified by parameters.

2 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002), p. 56.

3 Within classic videogames like Jet Set Willy we see elements that do not change (like the background) as well as moving elements (like an animated character that can be moved, buttons and score encounters). These moving elements are called ”sprites”. Nowadays the use of low-res sprites has become less common in videogames as the memory and processing power of computers increased.

4 Annet Dekker, “Assembling Traces, or the Conservation of Net Art,” NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies 3, no. 1 (2014): 171–93.

5 David J. Bolter and Richard A. Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

Further Reading

“Interview with Ben Fino-Radin,” interview by Crystal Sanchez and James, Smithsonian Institution Time-Based and Digital Art Working Group, April 23, 2013.

Main image

JODI, Jet Set Willy Variations (JSW011) (screenshot detail), 2002

ZX Spectrum software as 48K snapshots, ZX Spectrum emulator

Courtesy of the artists