The Feminist Institute

Engendering Parity for Women in the Arts

Intrigued by The Feminist Institute (TFI) and its ambition to provide a major online repository for the study of feminist documentation, VoCA’s Robin Clark sat down with the Kathleen Landy, TFI’s Founder, to learn more. The following conversation focuses on TFI’s efforts to archive the work of feminist artists based in the US.

ROBIN CLARK: I’d like to start by asking about the genesis of The Feminist Institute. How would you describe your motivation for launching this project?

KATHLEEN LANDY: I was a scholarship kid in college, and was trying to write a paper on some of the feminist artists on the west coast by focusing on correspondence between two of the instigators of the Feminist Art Movement. I couldn’t access the information because it was housed in archives at various universities. I didn’t have the funds to travel to those universities to open the boxes and complete my research. Fast forwarding to now, many of those important documents have still not been digitized, while the archives of equally important male artists have been.

So, for example, if someone is interested in writing about the history of Womanhouse, utilizing the correspondence between historian Arlene Raven and artist Judy Chicago, and they don’t have access to travel funds, it still won’t be an immediate possibility since those files are just now being digitized, after thirty years in boxes. Based on my own experience, I identified an urgent need and about a year and a half ago, we realized that there is a simple solution. We are now acquiring access to archives of feminist practice, cataloging them, digitizing them, and providing access to the information on a free, cloud-based platform. We then hold cultural events to promote this work, in order to share these rich histories in collaboration with the actual practitioners. It’s critical to do this documentation while many of these innovators are still alive and with us, so that they can tell their stories and preserve their own legacies. Digitizing this material will allow someone in, say, Australia, to research and create their own movements wherever they live, and then create an associated community.

CLARK: That sounds very much in line with what we’ve been working on at VoCA, particularly through our collaboration with the Joan Mitchell Foundation in which we produce public artist interviews as capstones to their CALL (Creating a Living Legacy) program. Videos and transcripts of these programs are available on VoCA’s website, the Joan Mitchell Foundation website, and will be archived at New York University’s Fales Library.

Would you please describe one of the cultural events you’ve organized, and the outcomes?

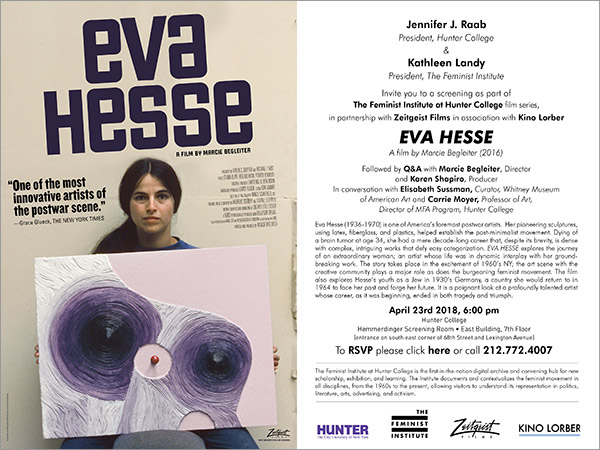

LANDY: The Feminist Institute hosts and collaborates on public programming with friends and partners at various points in the evolution of an archival process or relationship. We also act separately to promote women’s work and untold histories, often that resulted from the existence of an archive or that underscore the need to digitize a collection. Since 2017, for example, we’ve regularly hosted film screenings, including the premiere of “Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story” and a Q&A with Executive Producer Susan Sarandon and Director Alexandra Dean, as well as a screening of Judy Chicago’s “Right Out of History: The Making of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party” with Judy herself taking Q&A after the film. This fall, together with Faena, we held a few events in Miami—a conversation between Mickalene Thomas and Maura Reilly and then another with feminist artist Judith Bernstein and Perez Museum Director Franklin Sirmans. That followed with a visit to Bernstein’s studio by the Google 360-degree camera to capture it in situ. TFI is actively seeking a foundation partner to support the archiving of Judith’s studio in NYC. We were also thrilled to screen “Eva Hesse” in April of 2018 with Q&A with Director Marcie Begleiter and Producer Karen Shapiro in conversation with Whitney curator Elisabeth Sussman and Hunter College Professor and director of the MFA program, Carrie Moyer. That partnership has deepened, and with the support of the Eva Hesse Charitable Foundation, we will present more films that showcase the work of women in various fields.

Writer and curator Dr. Maura Reilly interviews artist Mickalene Thomas on Monday, December 3, 2018 in collaboration with The Feminist Institute.

CLARK: I had a chance to see the Judy Chicago show recently and was struck by a quote of hers that was printed in bold type on the wall of the ICA Miami’s elevator: “I believe that, at this moment in history, feminism is humanism.” What is your take on that idea relative to the mission of The Feminist Institute?

LANDY: Judy is a dear friend and it is on her shoulders that so many activists and artists of today stand. I think Judy really hits on the urgency this moment in history offers us to expand our embrace of women’s stories as humanity’s stories. We take the broadest possible view of feminism and really do have a big tent, as they say. We are less interested in defining a movement or requiring strictness than in documenting and including in the cannons all the women who have been omitted, overlooked, undervalued, or ignored. That exercise is at once feminist and humanist.

A lot of my early research was on Judy Chicago and she is a firebrand for the archival-context storytelling we are beginning to do; the content we are digitizing easily becomes the source material for documentary film making and public programs. So our work often aligns with hers and the notion that feminism as humanism resonates with the current call for intersectionality in feminist activity. For sure the future is female but so is the present, if we insist on it.

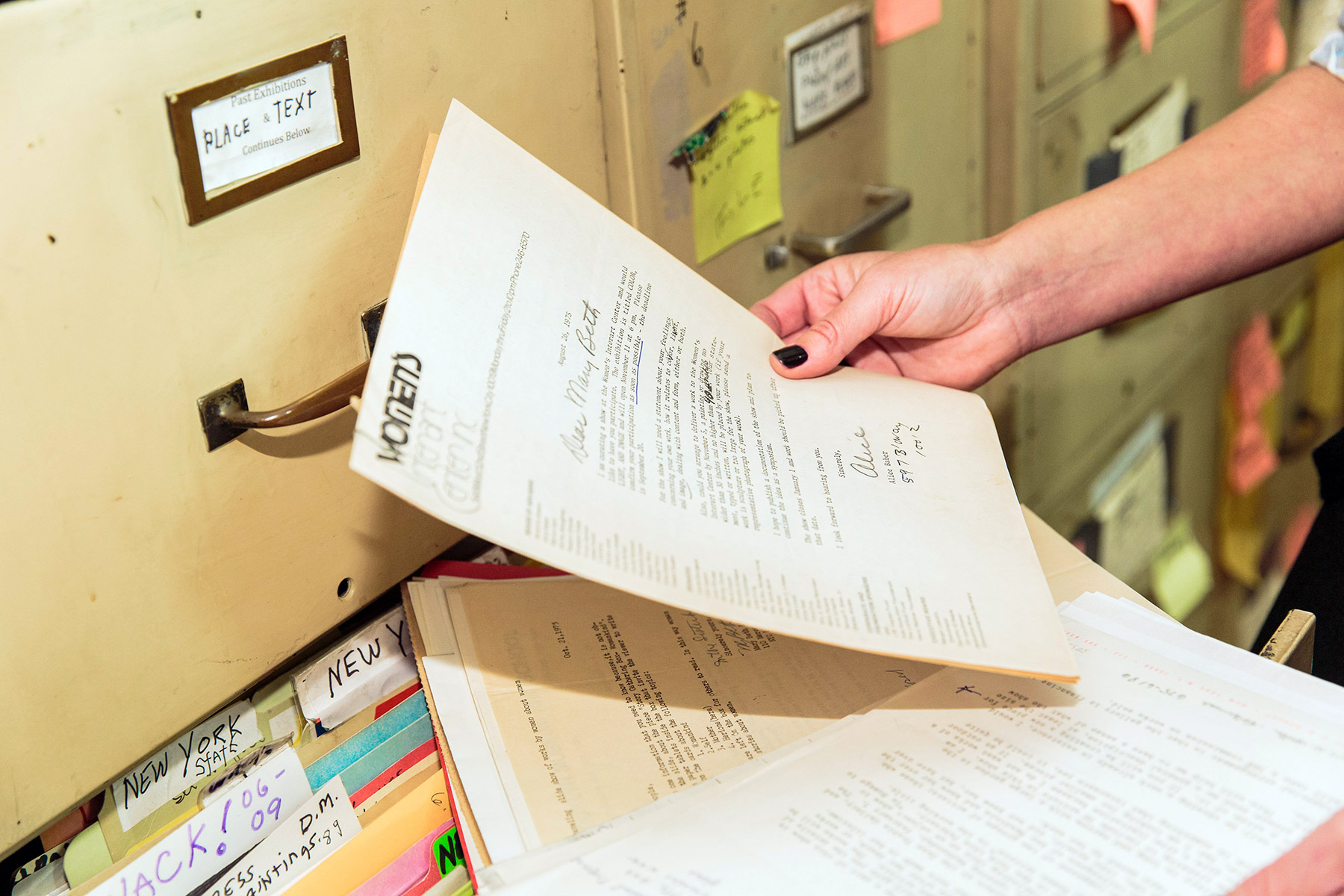

CLARK: Will you discuss one of your documentation projects in detail, perhaps the 360-degree visual cataloging of Mary Beth Edelson’s studio? How did that come about? What other materials are associated with that effort, besides the visual scope of her studio as she left it?

LANDY: I know, I’m really excited about this partnership. But let’s see, how did it happen with Mary Beth Edelson? I had heard that Mary Beth was not well. And having followed her career for many years, I thought I should speak with the David Lewis Gallery about preserving her legacy. Mary Beth was a huge influence in SoHo in its early years. She started the first battered women’s shelter in SoHo and hosted many of the Women’s Action Coalition meetings in her studio. That particular building itself housed part of the Fluxus movement, with Yoko Ono being a resident. We heard about the studio being dismantled and thought it would be important to catalog everything that was in there. We wanted to make sure that we preserved what we could so that, going forward, any student who wanted to understand that studio environment had access to the information. While we were unfortunately too late to capture the last interview with Mary Beth, we weren’t too late to preserve her thoughts, her notes, and her writings.

Artist Mary Beth Edelson’s studio. For the full 360 view, go to https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/iwLSn-zaI0_bLQ

When we walked into her studio we saw many things that actually needed to go into a library. The origins of A.I.R. (the Artists in Residence Gallery, the first all-female artists collective in the US) were there, and several letters with critic and author Lucy Lippard were in her files. The origins of the Women’s Slide Movement were there. It was a trove of information, and we thought that it should not just be put into archive boxes and put away in a library. We contacted NYU, because this was the history of downtown Manhattan at a critical moment, and they said, “Absolutely. We would like to be caretakers of this. We’ll come in and we’ll work with you on making sure that all of this is processed properly.” We developed a lovely partnership with NYU, which has now become the caretakers of the ephemera associated with Mary Beth’s studio. A key person who brought Mary Beth’s situation to us was Kat Griefen, who is on the board of A.I.R. It was a community effort for us to make sure that Mary Beth’s legacy was preserved. We brought Google’s 360 degree cameras into the studio last spring, which was just in time because now the studio’s been completely dismantled.

CLARK: It’s fantastic that you are able to do that. For future researchers wanting to understand Mary Beth Edelson’s work and her legacy, how are these materials discoverable or linked together? You’re doing the 360 photography, which is extraordinary and new. I’m wondering about the more traditional archival work of scanning the written materials. Who’s doing that and how is it being captured?

LANDY: Yes, absolutely. We brought on an archivist to begin to catalogue and digitize the contents of the studio. You can get a glimpse inside this process with Kat Griefen and Dr. Kathleen Wentrack in their contributions this month to the TFI guest-curated Brooklyn Rail; you can see the 360-degree view here. Like you, we are working in collaboration with Fales Library and with NYU more broadly.

As we are preserving the ephemera and documents, we are simultaneously developing our web-based platform that will make it all discoverable with a few clicks of a mouse. We recognize the timeliness, really the urgency, to do BOTH at once. Many of the innovators of the Feminist Art Movement are in later stages of their careers and it’s essential to document their lives right now, while they are with us to guide the process. Sadly, just in March we lost an amazing woman in Carolee Schneemann. TFI was lucky to be able to capture what may have been her last printed interview.

The aim of the platform we are developing will work with existing archives as well as our own collections to make them accessible through an easy, web-based search. We aren’t ready to announce the partnership or launch the platform quite yet. Ultimately the vision is to create a single portal to feminist work that had already been digitized (or will be) by our partners as well as the many unique archives and collections to which TFI is gaining access. It’s key that the digitization of the new materials is done so that they are easily captured by existing web search engines.

CLARK: As someone in the field struggling with these challenges, I am curious to know how you are tackling the problem.

LANDY: Funder by funder. It’s slow, but we are working with libraries and their archivists on staff. Actually, we could use thirty archivists. But as we’re going along, we’re developing relationships with various institutions who are excited about what we’re doing and would really like to have eyeballs on their holdings too.

CLARK: I think it’s wonderfully ambitious and really interesting. I’m keen to follow what you’re doing and to learn how it’s possible to scale it up. I know that many places struggle with the challenge of digitizing and even cataloguing materials in a way that will make them discoverable to researchers whether they are in position to experience the material first hand or not. Even creating an inventory of what’s there is an important first step.

LANDY: We’ve just hired a digital archivist who is working to formalize our process of connecting to existing digital collections and is also developing a system for naming and tagging records that we are newly digitizing with our content partners. She is also helping us to evaluate the existing digital archiving platforms and customizable software options to determine what is best for the database we are building. We are committed to starting with a framework that anticipates a lot of upcoming innovation in eradicating search bias so that in addition to populating online material with more feminist content, we are also an agent in making that content more findable by any user. We know we’ll have the attention of intentional researchers. How do we also get our content in front of any user in response to a related general search?

So many women artists have been under-appreciated, under-sold, under-represented in art history, and just plain under-valued, you know? The work we’re doing only highlights the fact that there is so much more that can be done. We’ve certainly made some progress, but I think long after we’re gone, Robin, there’s still going to be this issue. At least we’re chipping away at it as best we can.

CLARK: It sounds as if your project is very much still in a prototype phase. Would you say that’s true, that you’re building a foundation now for how it can go forward?

LANDY: We are building this deliberately and to be long-lasting and influential for a generation or more. We started by creating a stellar board—of all women, mind you—that can help us achieve these means. We look forward to sharing with you and your readers the launch of the platform in the coming months and, archive by archive, our acquisitions.

On March 14, 1979, Mary Beth Edelson and Ana Mendieta hosted a costume party titled “Come Dressed as Your Favorite Artist” in honor of Louise Bourgeois. Guests included: Louise Bourgeois, Ana Mendieta, Mary Beth Edelson, Michelle Stuart, Joyce Kozloff, Hannah Wilke, Judith Bernstein, Anne Sharp, Susan Copper, Edit D’Ak, Barbara Moore, Patricia Hamilton, Phyllis Krim, Barbara Zucker, Poppy Johnson, Marcia Resnick, and Gloria MacDonald.

CLARK: We look forward to learning more about the launch of the platform as soon as you are ready to share it. Meanwhile, would you talk a bit about your ambitions for public programs and a physical cultural center?

LANDY: Right now, we’re building institution by institution and it’s almost like we’re a circus, a very well-organized circus. There is an idea that we can be in as many universities and cultural centers as will have us, in order to spotlight their archives through programming and through our web interface. Key partners include Hunter College, Museum of Arts and Design, NYU Fales, Rutgers, A.I.R Gallery, Pen & Brush and many individual artists. Honestly, there is so much energy around this. I have excellent conversations almost every day about a new partnership, an archive in need, a great woman worth highlighting. It becomes a matter of capacity to get to it all and do it right.

As I mentioned, we have been doing public programming since day one of our existence and continue to plan exciting events for 2019 including the Eva Hesse Film Screenings, panel discussions and more. Eventually we would love to have a cultural center that could host researchers as well as public programs. But to have the greatest impact, we have to live on the cloud first. That’s the immediate goal of The Feminist Institute right now.

Eva Hesse documentary screening at Hunter College on April 23 2018. Pictured here in the panel are Elisabeth Sussman, Karen Shapiro, Marcie Begleiter, and Carrie Moyer.

CLARK: Can you talk a bit about how you’re building these partnerships, with examples of how you’re coming together with folks and how you’re finding common goals in your missions?

LANDY: Well, first and foremost, a lot of these relationships with the partners come through the support of our amazing board. We’re also finding that folks are coming to us in the spirit of collaboration and saying, “How can we help each other?” This is a unique moment in our history as a nation, and we’re all coming together to try and make a difference. Rather than holding the cards, you know, very close to the chest and being proprietary about information that could help each other, people are reaching out and saying, “Let’s get this done now. We need to make some change, so let’s work together to make it happen faster.” The idea of feminism itself has changed over time, becoming more inclusive perhaps than it was in the sixties. Now we’re seeing a moment of coming together across disciplines—in tech, in finance, in the arts—and building new language around that. Which is exciting.

CLARK: Could you say more about that? I mean, with feminism so central to the identity of your organization, do you have a working definition of what that is now?

LANDY: Well, I think we can borrow from Judith Bernstein here, who says that it is about equal access for women. She wanted a chance to have what the boys had. Not it, just equal access to it.

CLARK: When you’re out giving talks about what you’re most rigorously advocating for, how do you frame that? And is there any difference in the way that you think about it when the people whose work you’re showcasing are visual artists and when there are people from other sectors, which we haven’t really touched on yet?

LANDY: We could say in basic terms a feminist is a person who believes in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes. At The Feminist Institute, our particular piece of the fight for gender equality comes primarily in our efforts to make visible the work of women in the way men’s work has more consistently been visible. There is work to do and being done towards equality along other lines, too, but ours focuses on the gender gap, specifically. And yes, it carries to other sectors and disciplines. Shirley Chisholm’s legacy, for example, seems to be experiencing renewed interest; her documentarian serves on our board and is an example of someone who relied on an as-yet-digitized archive to tell a story that needed telling. Or take Muriel Siebert. She was the first woman to hold a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, right? So, I think about how hard she’s had to fight to get that moment to kind of touch that glass ceiling. And I wonder if my daughters will know who she is.

The Feminist Institutes creates digital content featuring women and a vehicle to get to it so that going forward, we could make sure that that next kid doing graduate research on a shoestring can utilize this information, build on it, and draw strength and energy from it to create new scholarship and innovation.

Main image

Katie McCarty of the Mary Beth Edelson Foundation and Kathleen Landy, founder of The Feminist Institute, in Mary Beth Edelson’s studio. Photo Credit: Kolin Mendez Photography