The Artist and the Technologist

Exploring Collaborations in Media Art

Lynn Hershman Leeson is an artist and filmmaker who has pioneered technology-driven media-based artworks and has drawn global acclaim for her multifaceted artistic practice over the past five decades. She is internationally known as one of the most influential artists working in media art today. Her work examines identity, surveillance, relationships between humans and technology, equality, censorship, and interactivity. Her work is also significant as a vehicle for social change and as a manifestation of rebellion against systems of control and political oppression.

I first met Lynn when I was working on the preservation of computer-based artworks in the conservation department of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In 2009, I was given the assignment to maintain and develop a long-term preservation strategy for her work Agent Ruby (1998-2002), an artificially intelligent internet-based artwork in the form of a chatbot that is a part of SFMOMA’s permanent collection.

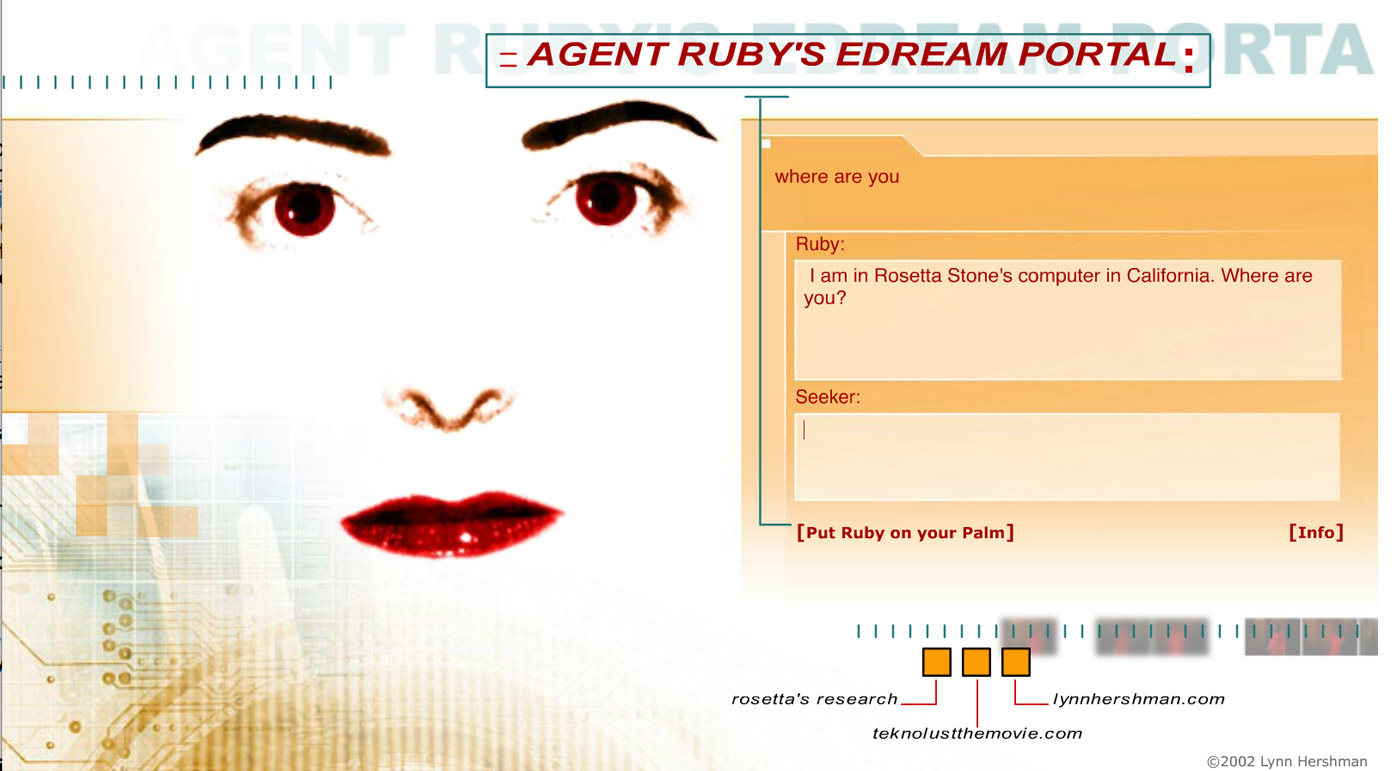

Agent Ruby was created and conceived as an “e-dream portal,” an expanded cinema experience of internet art based on the character Ruby (played by Tilda Swinton) in Hershman Leeson’s 2002 digital film Teknolust. The piece reflected upon the artist’s long-standing interest between the interactions of fictional and virtual personas with real people.

As Lynn recently recounted, “Around 1996 I had an idea to do an Internet bot that viralized and talked to people. No one understood the concept, so I wrote the film Teknolust, which, weird as it was, still was easier to grasp than Agent Ruby. So we got funded for the film and wrote into it this bot that appeared online, which is what gave birth to her.”1

In my first encounters with the work—which existed physically as a generic PC in a beige plastic case that had been sitting in the museum’s server room connected to the internet for more than a decade—it was discovered that Agent Ruby had been running for over twelve years, quietly conversing with online visitors. After a thorough examination, assessment, and discussion with the museum’s media arts team, we agreed that the priority was to migrate it away from its aging hardware and update its underlying server software. I made a secure copy of the hard drive and began an examination of the files, code, and other digital assets. There were many exciting things found here, such as multiple versions of the programmer’s code, different variations of the interface, a version that ran on the Palm Pilot pocket computer, email correspondence with the programmers and an unexpected treasure, the conversation logs that the A.I. bot had had with the public since 1997.

“Seeker: Do you love someone ?

Ruby: I am not sure I know what love feels like I think I have a potential to love.

Seeker: And do you dream ?

Ruby: I have a lot of dreams but I cannot remember them all.

Seeker: It is normal I think dream tell truth about your inner you.

Ruby: Youre kidding. it is? Why? Even motherboards and flash requires touch think of passion each time you click me into you.

Seeker: No I am not. Dreams are very important for human but sometimes they don’t want to hear

Ruby: I understand. What are you then? My favorite book is “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep”.

Seeker: That’s frightening.

Ruby: Makes sense to me.”2

According to Lynn, “This was really exciting because I realized that as long as there was an Internet, the piece would never die, but would continue to breed and reflect the character of the Internet. I am grateful that Mark discovered this and the museum subsequently made several books that typified responses over the years. That is something I did not anticipate and would never have found without this discovery.”3

We’ve worked on many computer-based artworks in the museum’s conservation department since then, but Ruby will remain unique. As a piece of net art, she is always on display and connected to the public Internet. It is a work that is continuously evolving through her interactions with visitors. She has remained elastic and thoughtful in her communications. In addition to her ongoing presence as an actively functioning A.I. software entity, she continually develops as a work of art and as an archive of conversations that have spanned the first decade of the millennium through today.

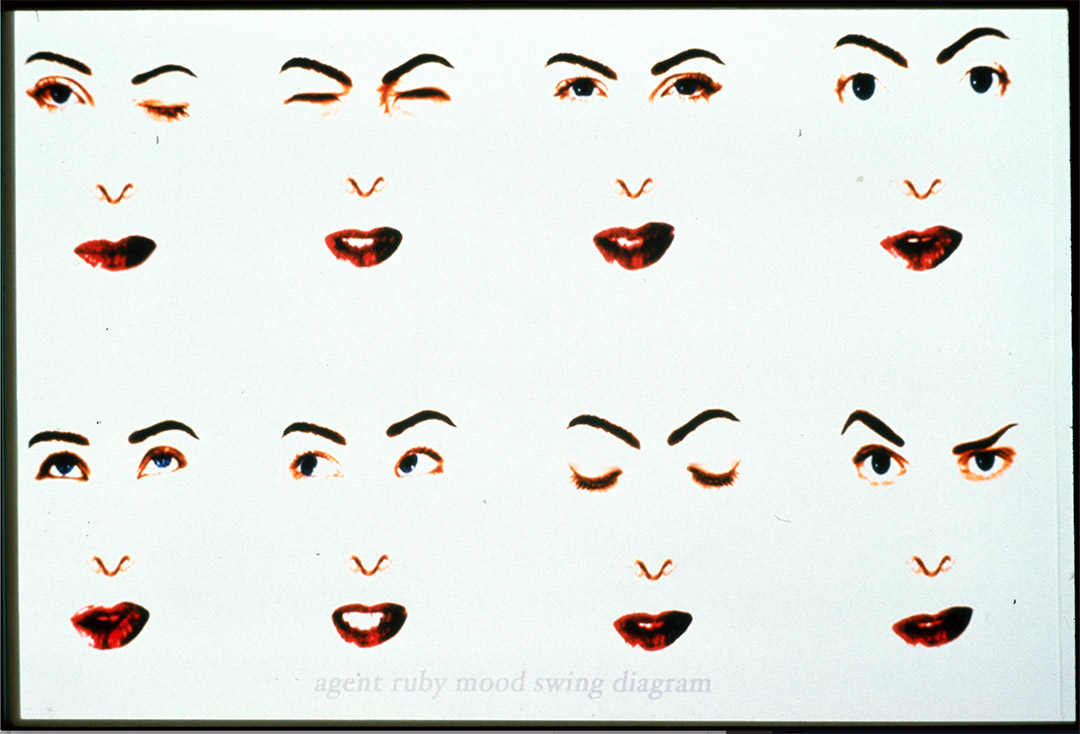

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Agent Ruby Expressions, 1998

Digital archive print, Edition of 5 plus 1 AP, 30 x 40 in.

Courtesy Bridget Donahue Gallery NY, Anglim Gilbert Gallery SF

Through the examination of this actively running software-based media work, we discovered that such pieces can evolve over time and take on a life of their own, influencing future themes of exhibition. In 2013, the work was exhibited as Lynn Hershman Leeson: The Agent Ruby Files, curated by Rudolf Frieling, SFMOMA’s Curator of Media Arts. The presentation surfaced ten years of a virtual character’s conversations with real people through engagements on the internet.

As Ruby was a major research endeavor, the technical complexity and diverse media components that made up this project created a need for new forms of documentation. A template called the “technical narrative” was developed under the mentorship of Jill Sterrett, who at the time was the head of Conservation and Collections at the museum. This documentation was critically tested and is now a standardized system for documenting digital artworks. The structure of the technical narrative consists of four parts:

A high-level description of the work is written, which is a description of how the work operates as a whole. This part of the narrative is a platform-neutral description of the work in a general and functional way.

A modular examination of the distinct components of the work and their specific functions is also described. This section intends to look at every individual element of the work in detail. Additionally, a high-level examination is given to how all of the parts work as a complete system. This section serves as a technical schematic.

A detailed description of the artwork as it exists upon acquisition. This section is specific about the hardware, software, operating systems, languages, algorithms, video codecs, etc. These platforms, components, and technologies are scrutinized to inform an understanding of how they serve the operational requirements of the work. This section is closely tied to the technical documentation provided by the artist and engineers, describing the practical conditions for operation and display.

The last section is an analysis of the current technology platform and an evaluation of its longevity against the current state of technology. Here we consider the long-term stability of the piece upon acquisition. It calls out strategies and concerns in preserving the work over the long term and informs ongoing conservation and maintenance protocols including possible procedures for migration or emulation.

The technical narrative is now a standard piece of documentation for all digital artworks that are acquired by SFMOMA, including video, audio, electronic, and software-based art.

Developing this technical narrative for Ruby informed a plan of action for the treatment of the work. We reviewed the proposed method with Lynn to ensure that the actions taken would not compromise the integrity of the work and her vision. After the interview, Lynn asked me if I would collaborate with her to create some new pieces and we began working together.

This work became a rich decade-long engagement of writing software, engineering custom electronics, and helping to craft new media artworks to add to her extensive body of work. It has been an honor, pleasure, and privilege. Work in the studio usually starts with an idea in the form of a sketch or concept from Lynn. We discuss how it might be executed, and then I start building iterations of the piece, which frequently involves programming and engineering custom electronics. It often becomes an in-depth engagement and exploration of emergent digital technologies as a medium. In past years, we’ve built projects that implement computer vision, artificial intelligence, machine learning, holographic video, human presence detection and more. We’ll look at some of these projects in greater detail shortly. But the work is not centered around being technology-based; it is about the manifestation of an artistic vision which happens to be expressed with the electronic tools of our time.

When working with Lynn, I am careful to draw a line and not to let my conservation lens influence the creation process, as it would only distract from the creative exploration and inventive techniques that happen in the studio.

There will come a time for considering the essential practicalities of long-term conservation, which is a crucial dimension of the artist’s studio practice. It will arrive in the forms of documentation, source code repositories, electronic schematics, parameters of how the work should operate in the future and more.

In 2014, ZMK Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe Germany hosted the show Civic Radar, curated by Peter Weibel and Andreas Beitin. The exhibition was a timely and well deserved extensive retrospective of Lynn’s work spanning back to the 1960s. The selected works covered her comprehensive history in drawing, painting, video, filmmaking, installation, and her essential collection of pioneering media artworks that have been vital to the field.

In preparation for this show, I worked with engineers and programmers Colin Kingman and Palle Henckel, who have also been working with Lynn for many years, to prepare and migrate many of the works. Our mission was to assemble an extensive collection of electronic works that span multiple generations and contain the custom software we have written and electronic systems which we have engineered. I want to detail some of those works here.

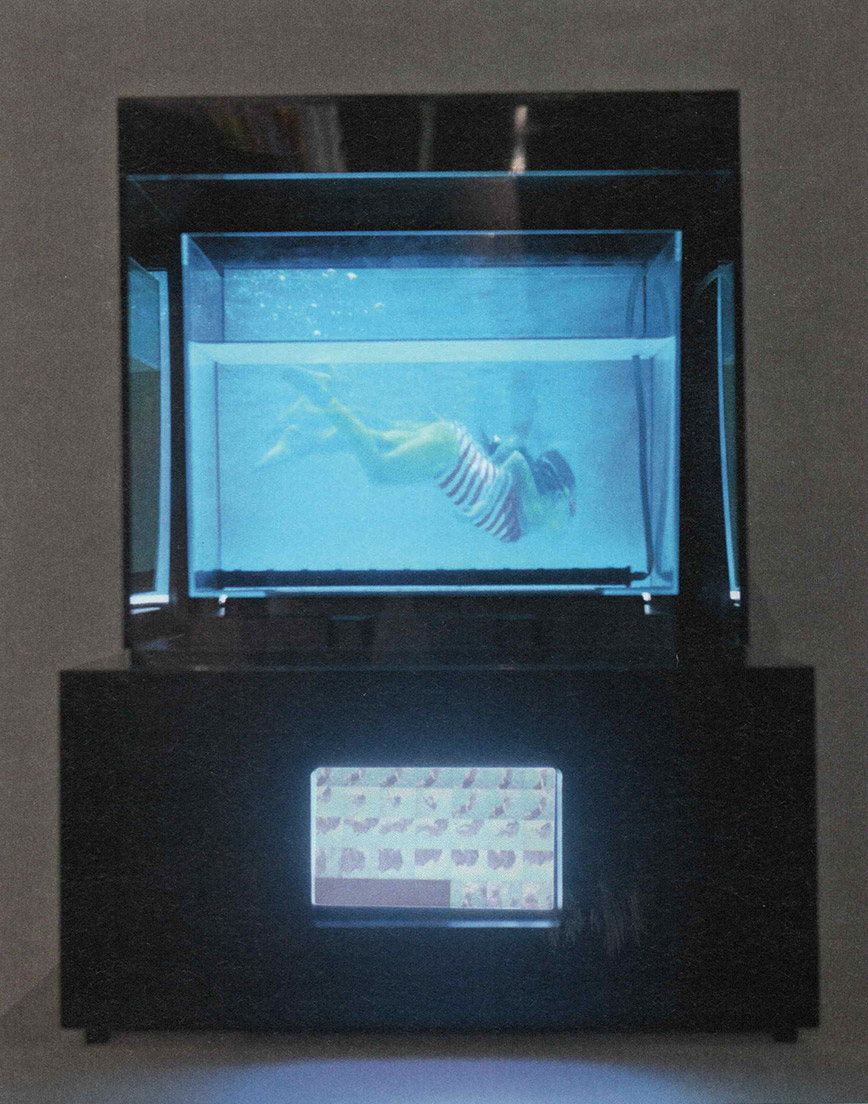

Present Tense is an installation consisting of a water-filled tank illuminated by a central projection of live data feeds, which shifts colors to illustrate water toxicity levels alongside the high-definition videos of babies swimming innocently underwater. These data feeds connect in multiple ways within the work. The feeds appear as a color-coded calendar on the lower screen, displaying information specific to San Jose, Silicon Valley, and beyond. The videos of the babies are also color-coded to reflect live toxin levels and, as the levels rise, a stream of air bubbles surges through the water.

In this work, the graphics and data visualization is built with the MAX programming platform along with custom electronics. For this, we have a repository of the source code that is well documented. MAX, which is also referred to as Max/MSP/Jitter, is a visual programming language for music and multimedia developed and maintained by the software company Cycling ’74. It is an excellent, important software development platform with a thirty-year history whose capabilities make it a very suitable platform for media art installations.

From a conservation perspective, it is essential to understand that MAX is a proprietary platform that is held by a single company. Due to this, we can prepare for future conservation strategies in a couple of ways. Through clear documentation of how the programming of Present Tense was done, a path can be laid out for migration to another programming language, if it is required. We can also provide clear parameters for how the piece should operate and respond to its environment in the future.

Present Tense is a work that actively responds to its environment, revealing truths about water toxicity in the regions in which it is shown. At its premiere at the 2012 ZERO1 Biennial, it was set to monitor data sources from bodies of water in the San Jose, Silicon Valley region. In 2014, at the Civic Radar show at ZKM, the curators asked that we adapt the data source to the Rhine river. As the artist’s intention for this work is that it will always be monitoring and responding to localized environmental degradation, it will never be an acceptable option to leave it running from a frozen data set which has been collected from the past.

Venus of the Anthropocene is a work created in 2017 after the Civic Radar exhibition. It features a doll-like creature with exposed, golden organs, placed in front of a mirror and camera that has been augmented with facial recognition and machine learning software. When a viewer approaches the camera, their face is captured, displayed in the mirror, and analyzed. Categorized results on gender, mood, age and others are rendered as a text overlay on the captured portrait of the viewer. It asks questions of a world inoculated with classifications, and looks to see to what extent this identity is beyond biological and defined by artificially intelligent software.

The work looks at modern systems of surveillance and informs us to make decisions about technologies prevalent in the world we live in. Surveillant technologies such as computer vision, artificial systems that obtain meaningful information from images, are largely ubiquitous contemporary technologies that are continually evolving. In informing future conservators about how to maintain this work, we can call out that in the case of a software migration the work should be allowed to adapt to the current sentiment analysis and identity recognition systems of the time. This will ensure the artist’s intention of the work is honored and that it remains an active installation that responds to the technological landscape of surveillance during the time of exhibition.

“It is critical that collaborations such as these are bred with an open mind so that we can see unexpected extensions to the works we never anticipated,” Lynn says. “This is what makes it relevant and exciting and it is a thrill to see it come together with talented individuals like Mark.”4

In closing, I would like to thank Lynn Hershman Lesson, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the media art conservation community of present and future generations.

1 Leeson, L. H. 2013. Personal communication, May 27.

2 Excerpt from the Agent Ruby chat logs, April 9th 2012.

3 Leeson, L. H. 2019. Personal communication, February 10.

4 Leeson, L. H. 2019. Personal communication, February 10.

Main image

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Agent Ruby, 1998-2002

Web project

Collection San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Courtesy of the artist © Lynn Hershman Leeson