Sun Cycles

The New York-based artist Mary Lucier has been working in video since the 1970s. Through a range of installations, she has often reimagined 19th-century literary and artistic approaches to landscape and pictorial narrative through contemporary lens-based technology.

I met with the artist in November 2018 when Equinox (1979), an example of her pioneering multi-channel video work and signature burning of the video camera’s eye, was on view at SculptureCenter in Long Island City, New York as part of Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 (September 17 – December 17, 2018). Conceived by Henriette Huldisch, Director of Exhibitions and Curator, MIT List Visual Arts Center, where Before Projection was first presented, this focused survey reevaluated a period in video art in which artists such as Takahiko Iimura, Shigeko Kubota, Nam June Paik, Adrian Piper, among others, engaged with video monitors as sculptural objects. Our conversation focused on Lucier’s early forays into time-based media performance and installation and the contributions of women artists in that era.

Tanya Zimbardo: Before Projection was the first time I’ve experienced your work Equinox (1979). I was initially struck by the remarkable quality of the color footage.

Mary Lucier: It’s the color that gets me now, on many levels. I even think of the California fires now, when I look at that color. The tube burns are actually very light, whereas in Dawn Burn (1975), the burns are quite dark, like charcoal marks.

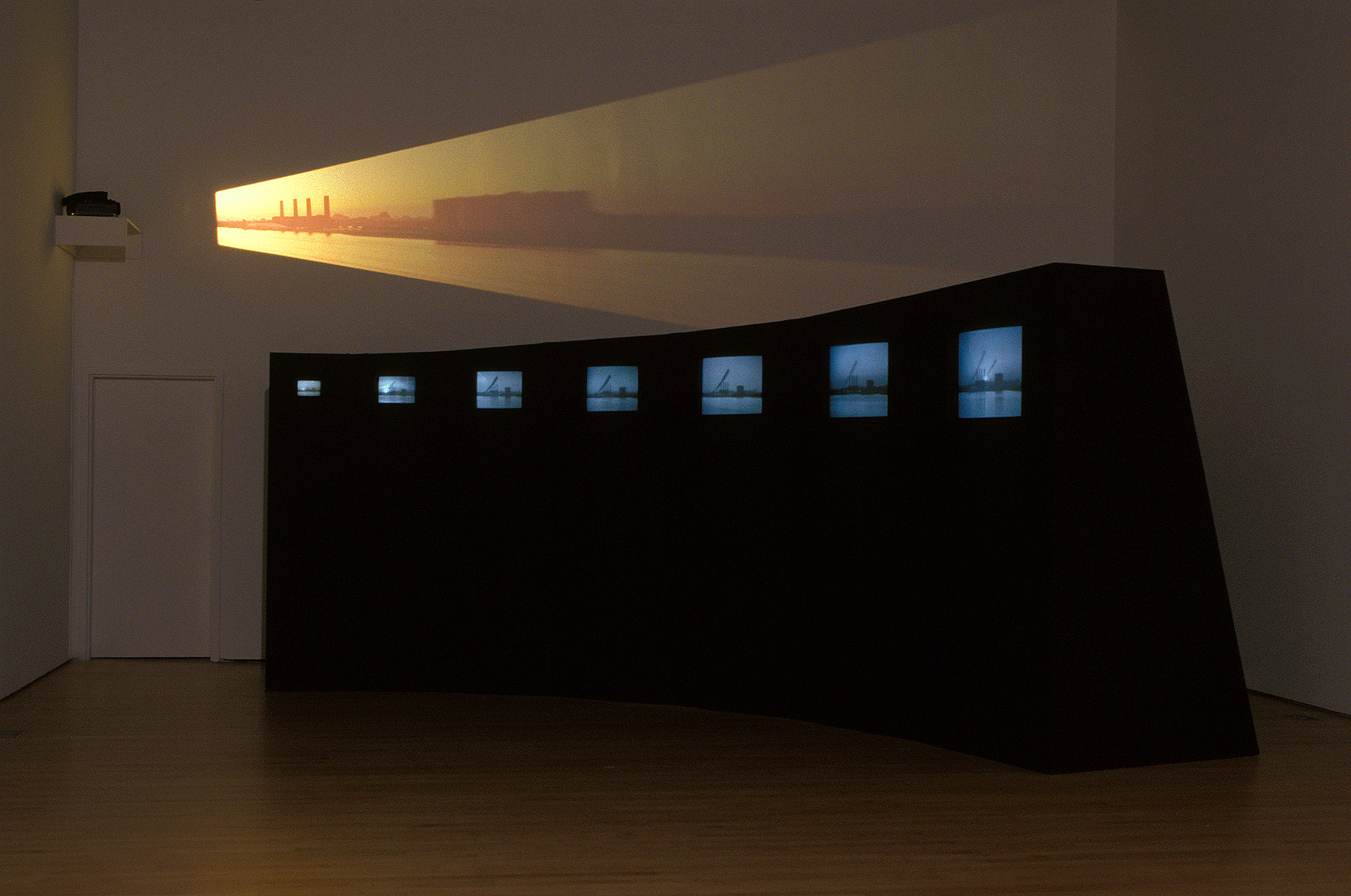

Equinox (1979) was first shown in its reconstructed form in The Sun Placed in the Abyss (2016) at the Columbus Museum of Art. Drew Sawyer, the curator, was interested at first in Dawn Burn. I said, “I have a better idea. How about Equinox, which is in color and has never been shown since it was first done?”1 So I set about recreating Equinox, revising both the video and the structure. I decided I would use only three monitor sizes (20, 25, and 32-in.) that I owned, instead of trying to source all seven different sizes. It still approximates the crescendo that I wanted this piece to be. I did edit it a bit, I confess, when I converted it to digital.

Mary Lucier, Equinox, 1979/2016 (installation view at SculptureCenter, New York, 2018)

Seven-channel video installation, with sound, 33 minutes, 212 × 68 × 94 ¼ in.

Courtesy the artist and Lennon, Weinberg, Inc. Photo: Mary Lucier

Zimbardo: Could you tell me a bit about the original recording process and the multi-channel soundtrack?

Lucier: I recorded Equinox from the west side of Manhattan, looking east. (Dawn Burn was recorded from the east side.) I shot across town from a friend’s apartment on the 35th floor of Independence Plaza in Lower Manhattan. The skyline has changed drastically in 40 years. It’s filled with high rises now. But then, I had a perfectly clear view of the sun rising. As the sun rises, it burns a permanent mark on the camera’s recording tube. I decided to follow the sun from the initial wide shot on Day 1. The next day I zoomed in a little, then a little bit more each day, until finally I was focused on just the sun itself. The streaks are the accumulated burn marks that occurred over each of seven days. Same camera, same view, but slightly zoomed in each day. I did not record seven successive days because on cloudy days you don’t see the sun. That happened with Dawn Burn too, which is why some of the marks are so far apart.

The soundtrack is simply the sound of the city each day. For the most part, it’s just a roar, but there are some incredible small moments that poke through. In channel four, for instance, there’s a sound of things knocking together, like milk bottles. What could that be? I was on the 35th floor, what are we hearing? But I love that sound. In the very beginning of Channel 1, it opens with the sound of a siren. It’s got the real feel of the city.

Dawn Burn was shot directly on the east side, over the East River, with the sun rising over four smoke stacks in Queens. I was at another friend’s apartment where I could see the traffic on the river. I put a plug in the audio input of the recorder, so that it couldn’t possibly record any sounds. I could at least have recorded it and then rejected it later, but I was such a purist in those days.

Zimbardo: Do you recall where you first encountered video work in New York?

Lucier: I don’t recall where I first saw video work, but it would have been in the very early ’70s. When I was living with Alvin Lucier, who was teaching at Wesleyan in Connecticut, we would often come down for avant garde music and dance concerts, so my world in those days, centered, more on the performing arts, which I thought were definitely in the forefront of art at the time.

I was friendly with Shigeko [Kubota] and Nam June [Paik] and sometimes hung out in their loft in Westbeth. Later, they moved to a huge space in SoHo. I was always aware of what they were doing and I photographed installations and off-screen video for them. In those days, I doubled a bit as a documenter of performance. I was never a Peter Moore, who photographed everything and everybody. But for a period of time, I helped earn a living as a photographer after I first moved to New York. I did a lot of shooting at The Kitchen. That became sort of an essential part of my existence. I also photographed at DTW, Dance Theater Workshop, which is now New York Live Arts, working with choreographers there. My favorite was Elizabeth Streb. She and I subsequently worked together for a period of time in the late ’80s and early ’90s and we did three major pieces, both multi-channel installation and single-channel for broadcast.2

Zimbardo: How did you meet and begin to collaborate? What aspects of her practice interested you?

Lucier: Elizabeth and I had met in the mid-70s when I was documenting the Viola Farber Dance Company’s performances in the streets of New York. She was, at that time, studying with Viola and had volunteered, along with a number of other younger dancers, to participate in these street dances, carrying audio tape players emitting sound. Later I became interested in Streb as a radical choreographer and powerful performer in her own right. Her ideas were very advanced for the time, as they still are today, and she developed an extreme, physically bold kind of choreography that put her and her dancers at some bodily risk. I always felt that she brought me back to my own radical ideas about video and the visual image in the way she examined movement in a non-traditional context that was not related to any other post-modern, contemporary dance at the time.

Zimbardo: Were there key shows for you at The Kitchen, or other spaces, in which you saw video work presented in a performance event or in a gallery context?

Lucier: I participated in one of the Avant-Garde Festivals, the one on the train in Grand Central Station in 1973.3 Every artist had a railroad car, and there was a lot of video. The video artist Davidson Gigliotti had a piece called Hunter Mountain (1973) which featured three large CRT monitors, side-by-side on the floor, each one showing a different aspect of Hunter Mountain. All together it made a kind of panorama. I think that was extremely influential for me in thinking about video sculpture, not only being sculptural in a space, but portraying a natural sculptural form like a mountain.

The other person was Beryl Korot. The first piece of hers I saw was Dachau 1974 (1974), which is the four-channel piece that she shot in the infamous concentration camp. It was a very austere, pared down, four-channel black-and-white work. I photographed that at The Kitchen when she first showed it there. I would say those were the two most influential pieces in my early formation in video.

I had first started working in sculpture and literature, then photography and performance, and finally video installation. Video installation brought together all the things I was interested in—the flat, but moving image, sculptural spatial considerations, and the ability to import imagery from the outside world.

Zimbardo: Dachau 1974 and your Dawn Burn are featured in Video Art: An Anthology (1976). You joined co-editors Beryl Korot and Ira Schneider in editing that book, which is still an invaluable resource on a range of approaches to video and artists’ writing. It’s often been noted that there was a greater gender balance in the loose network of video communities compared to other genres. I am curious about your perspective on that.

Mary Lucier, Dawn Burn, 1975/1993 (installation view at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2004)

Seven-channel video installation, silent, and single slide projection, 98 x 45 x 54 in.

Collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund: gift of Doris and Donald

Fisher, Marion E. Greene, Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr., and Leanne B. Roberts

Photo courtesy Mary Lucier

Lucier: I would definitely say so. There were major women artists like Joan Jonas, Hermine Freed, Beryl Korot, Shigeko Kubota, Nancy Holt, and many others who got into video early on. Video in the beginning was accessible. We got a hold of the equipment, we used it, and we were accepted. Yes, it was much more receptive to women and I think some of the collectives, like the Videofreex and Raindance, helped in that they were mixed in gender. Much has been written about the prevalence of women in early video. I think it is hard to say why this was so, especially because it was a technical medium, which normally does not attract women so readily. For me, it had to do with the “liveness” of the medium and the fact that there wasn’t a lot of historical baggage attached to it. It was fresh, and one felt it could be used as an experimental tool without accounting for a heavy history of great art to overcome or to learn from, unlike painting or even film. It felt free, and I felt free while using it. I felt that my colleagues and I were writing the book, so to speak, establishing the first parameters for creating and evaluating work.

Zimbardo: I am reminded of the fact that Video Art: An Anthology included your friend Mary Ashley (1931–96) and her rarely seen three-hour video work Eat Your Totems (1974). She had been a force in the ONCE group in the ’60s. Could you speak to your respective participation with Sonic Arts Union (1966–76)?

Lucier: The Sonic Arts Union was originally a group of male composers [David Behrman, Alvin Lucier, Gordon Mumma, Robert Ashley] aided by four women artists. We accompanied them and helped perform their works on several international and American tours. We often performed collaborative pieces, as well. At a certain point all of the women ceased to be part of the group. When the remaining three members performed here recently at ISSUE Project Room in Brooklyn, I posted a comment on Facebook: “Don’t forget the women artists who traveled, collaborated, and performed with the guys all those years: Mary Ashley, Shigeko Kubota, Barbara Lloyd Dilley, Mary Lucier.” I wanted to make the case that we were essential in many ways.4

In Mary Ashley’s piece Soft Centers, the women were hoisted up on the men’s shoulders and were kind of jousting with one another to the Ray Charles song, Cryin’ Time Again. Imagine those guys getting us up on their shoulders! They’re not muscle men, they’re composers. It was a very physical piece in which we could all be involved and it was great fun. I was very interested in Mary’s take on female cooperation, but also female domination.

Zimbardo: I believe you developed your Polaroid Image Series (1970) in relation to Alvin Lucier’s I am sitting in a room (1969).5

Lucier: My Polaroid works evolved through a similar process as his audio tape. I produced a series of slides that were derived from a single Polaroid image of the chair in the room where Alvin had made the recording. I took a Polaroid snapshot of the chair in that room and then I subjected it to a copying process similar to what he did with the audio piece where he recorded a statement, played it back into the room, recorded it again as it played back, played that back and recorded it many times until pretty much the legibility of the text is gone and what’s left is largely what Alvin describes as the ambient frequencies of the room. It becomes very bell-like at the end. I made 51 generations of the ROOM image, copying each generation until it became abstract, unrecognizable as an image of reality. I did this with maybe 10 different Polaroid images, which I subjected to the same copying process.

The first time this slide piece was shown was at the Guggenheim Museum in two nights of concerts by the Sonic Arts Union in 1970. Alvin now performs it live, without the images but in the beginning it was a tape music piece. Recently, people seem to prefer the drama of a live performance. For a recent performance in Russia, I was asked for my images to accompany the performance. Alvin performed onstage live with these gigantic projections changing behind him. I thought it looked quite terrific.

Zimbardo: It was also included in Chrissie Iles’s landmark show Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–77 (2001) at the Whitney Museum of American Art. For several artists, that exhibition was critical in providing the first major occasion to revisit and restore work for display. Into the Light made an argument for video projection, which had become popular within a larger history of projected image works and artists’ film. Henriette Huldisch’s Before Projection hones in on a period of multi-monitor video sculpture before this cinematic turn in the late ’90s, and which can also be regarded as a precedent now for a younger generation of artists creating sculptural installations with flat screens.

Mary Lucier, Polaroid Image Series: ROOM, SHIGEKO, CROQUET, CITY OF BOSTON, with I am sitting in a room (score) by Alvin Lucier, 1970/2006

Four video projections of digitized slides, 23 minutes, Dimensions variable

Collection Milwaukee Art Museum, purchase, with funds from the Contemporary Art Society Photo: John R. Glembin, Courtesy Mary Lucier

Lucier: Into the Light was the first time that I am sitting in a room was shown with four of the slide images [ROOM, SHIGEKO, CROQUET, CITY OF BOSTON]. I had the slides restored to a clear black-and-white, because over time they had begun to turn magenta.

Zimbardo: When you have exhibited this work more recently, has it been important for you to try to maintain the format of analog slide projections?

Lucier: I showed the piece [Polaroid Image Series:ROOM, SHIGEKO, CROQUET, CITY OF BOSTON, with I Am Sitting in a Room (score) by Alvin Lucier (1970, digitized 2006)] subsequently at the Milwaukee Art Museum and they bought an edition of it. I had by then transferred this entire series to digital. I frequently show just the ROOM series by itself because it’s very iconic and classic. However, I recently performed it in its original analog slide form along with the audio file at the Fridman Gallery in New York, which was quite successful.

Zimbardo: Did the four women associated with Sonic Arts Union ever perform together?

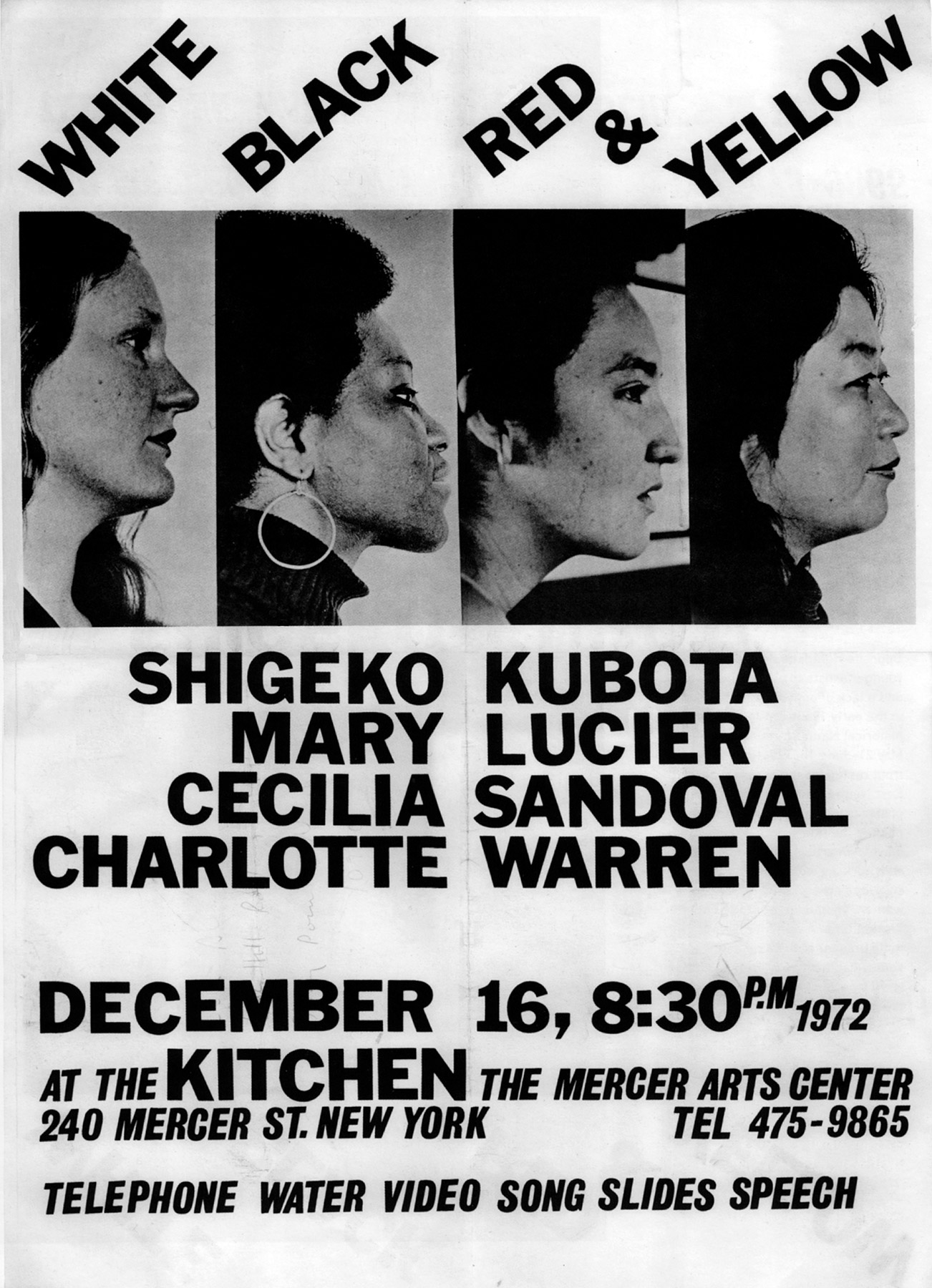

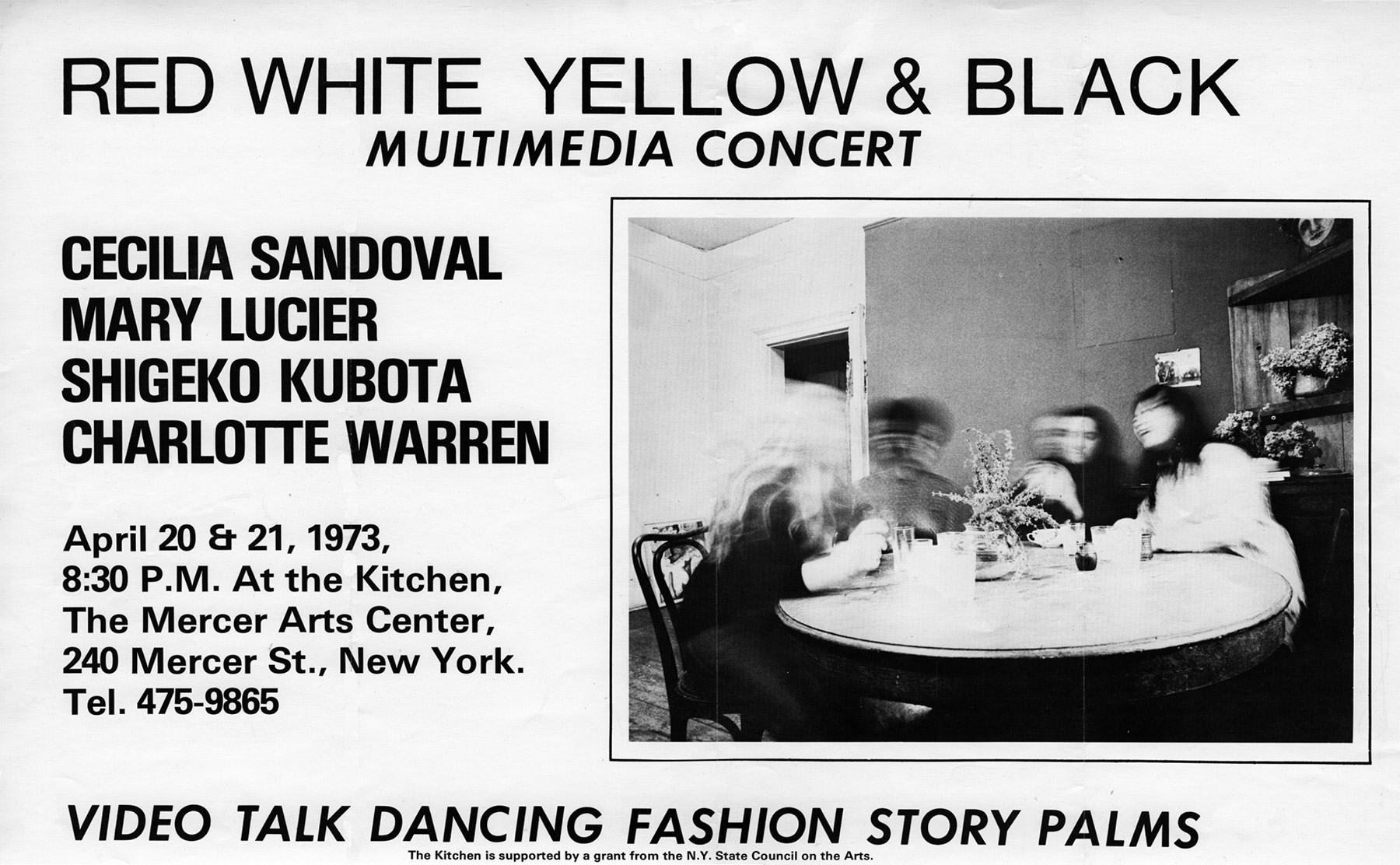

Lucier: No. However, what did happen, that I think was pretty interesting, was that Shigeko Kubota and I formed a group called Red, White, Yellow and Black, which did performances at the original Kitchen in 1972 and ’73. We were joined by a black poet named Charlotte Warren and my Navajo Indian friend, Cecelia Sandoval. It was certainly Shigeko’s idea to represent four races of women. We were multicultural before it was popular. Shigeko was forward looking in that respect. We had a platform for showing at The Kitchen, which was fantastic.

We were not a collective or even a group like Sonic Arts or the Once Group in Ann Arbor or Raindance. We were a loose-knit collection of friends who just wanted to do something in a more embracing context at a time when groups of artists were banding together, not only because of shared interests but to help promote one another. In some sense you could almost say that the formation of this group was Shigeko’s piece.

Cecelia and I collaborated on a piece called The Occasion of her First Dance and How She Looked, a rather strange interpretation of her dream. That was one of the first times I used video as a backdrop. I recited a text during the performance and at the end a Country Western song came on and Cecilia danced with members of the audience, speaking to them in Navajo.

Zimbardo: How would you describe the overall arc of your concerts?

Lucier: The bottom of the posters read something like, “telephone song water fortunes,” which was largely Shigeko’s idea of what this “concert” was going to consist of. She would present a video piece with a performance of her own. Cecelia was not present for the first concert. We called her long distance on the Navajo reservation.6 In those days it wasn’t easy to get a long distance call to be heard in the audience. In fact, you couldn’t always get through right away. Charlotte Warren read poetry, her own and others’ like Nikki Giovanni, and other prominent black women poets. For the first concert, I did a piece called Red Herring Journal (the Boston Strangler Was a Woman). I had been living in the suburbs of Boston and I was fascinated by this strange murderer who was on the loose, and hadn’t been caught yet and who seemed to gain access to women’s homes easily. The piece was a recitation of descriptions of female criminals throughout history. I had done a lot of research on the physiognomy of female criminals. I was seated at a table, reading into a microphone, and behind me were three screen projections of slides that showed the facial features of supposed criminal women. These were all very bizarre and dated concepts, which fascinated me. It had to do, perhaps, with my own feelings of breaking away from conventions at the time.

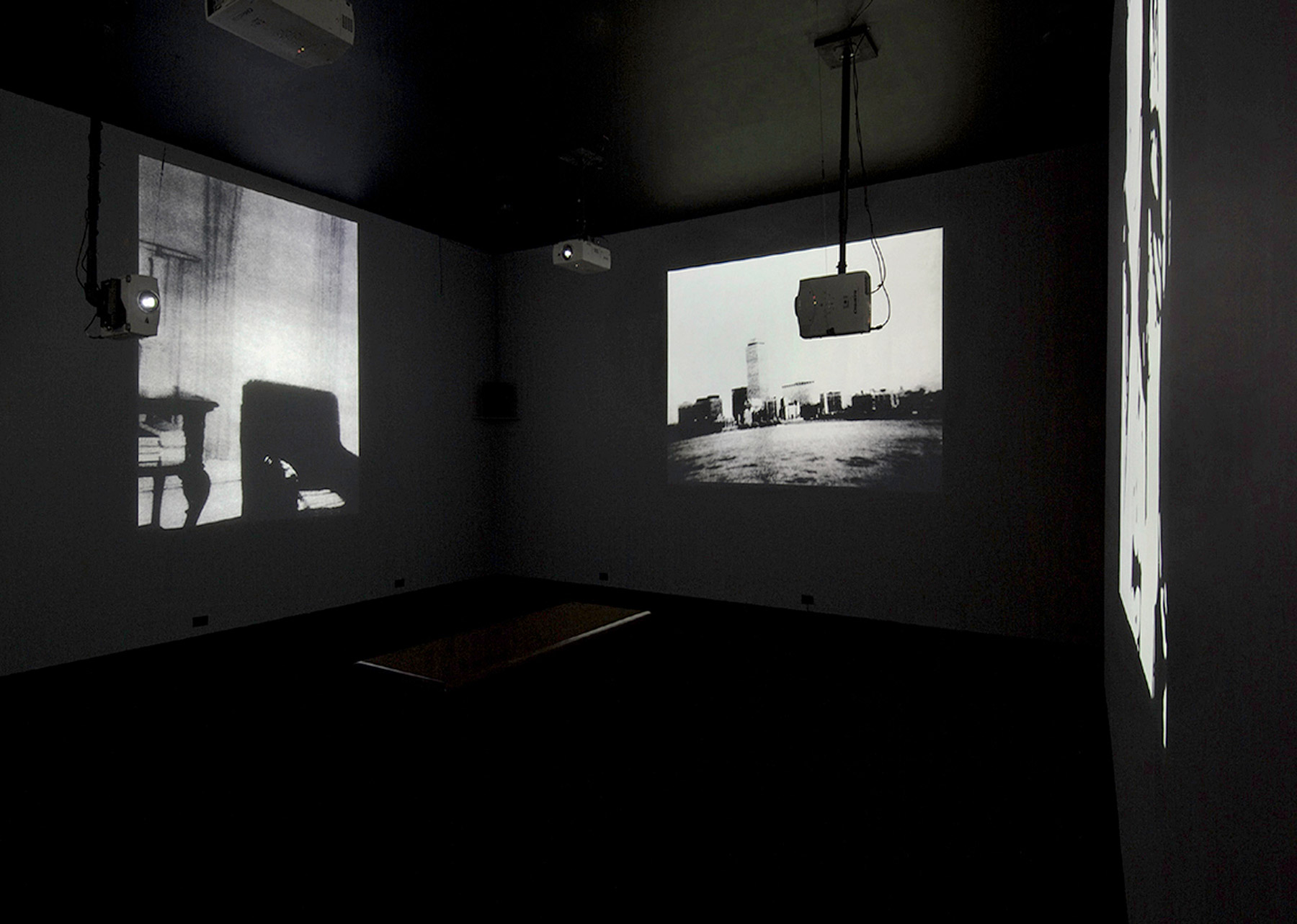

Mary Lucier, Color Phantoms in Automatic Writing, 2015 (installation view at The Kitchen, 2016)

Photo: David Allison, Courtesy Mary Lucier

Zimbardo: More recently you returned to The Kitchen as part of its 45th anniversary moment in 2016. You presented two video installations in tribute to Robert Ashley: Color Phantoms with Automatic Writing (2015) and The Trial (1974–2016). What was your process like in reflecting on your own history and the legacy of that space?

Lucier: Both pieces that I showed there were revisions of earlier works. The Trial, which was shown on monitors in the lobby during a Robert Ashley performance, was originally a single-channel tape shot at the Cunningham studio in 1974 with Ashley and Anne Wehrer as performers with a photographer and me also onstage as documenters of the work. For this revival at The Kitchen I divided the tape into three sections, presenting them simultaneously on three adjacent 4:3 screens.

Color Phantoms with Automatic Writing (2015) originated as a series of sandwiched, projected slides in 1972 as part of a collaboration with another composer. It was first revised in 2009 with Robert Ashley’s Automatic Writing (1979) and subsequently expanded to include the two-room environment that was presented at The Kitchen in 2015. Working with The Kitchen was somewhat nostalgic for me in that I had previously shown work at both the two earlier venues—the original space in the Mercer Arts Center (1972, 1973), the Wooster Street venue (1975 and 1978), and once before at the current 19th Street location as part of a collaboration with Elizabeth Streb (1985). It was a good moment for me to present that work, which encompassed so much of my image-making history.

1 Lucier’s Equinox (1979) was recorded March 9–21, 1979 and made its debut as a public installation in the semi-open space of the CUNY Graduate Center Mall on 42nd Street. Dawn Burn (1975) was acquired by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and was the subject of a preservation project in the ’90s.

2 Lucier and Streb’s collaborative projects include the two-channel video and performance Amphibian (1985), the televised single-channel video In the blink of an eye (1987), and two related works: the single-channel video Mass: Between a Rock and a Hard Place (1990), and three-channel installation MASS (1990).

3 The 10th Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York was held on December 9, 1973 at Grand Central Terminal.

4 In July 2018, ISSUE Project Room presented a two-day series observing the legacy of the experimental music collective the Sonic Arts Union and its founding members: David Behrman, Alvin Lucier, Gordon Mumma, and Robert Ashley (1930–2014).

5 For an overview of I am sitting in a room (1969) by Alvin Lucier, Mary Lucier’s first husband, see Martha Joseph’s “Collecting Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room,” Inside/Out, MoMA/PS.1 blog. www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2015/01/20/collecting-alvin-luciers-i-am-sitting-in-a-room (accessed March 1, 2019)

6 Shigeko Kubota’s single-channel video diary Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky was recorded in Chinle, Arizona, where Sandoval’s family lived.

Main image

Mary Lucier, detail of Equinox, 1979

Photo courtesy the artist, © Mary Lucier