Stewarding a Living Artwork

The Conservation of the Nevelson Chapel at Saint Peter’s Church

At the center of this story is the Erol Beker Chapel of the Good Shepherd, widely known as the Nevelson Chapel, a permanent, site-specific installation created in 1977 by pioneering American sculptor Louise Nevelson.

The Chapel is situated within Saint Peter’s Church (SPC), an Evangelical Lutheran church in New York City that struck a deal with Citicorp bank. It sold its land and air rights to its 54th St and Lexington Ave site and in exchange was able to build a new church and become part of a cooperative ownership arrangement in the new 59-story bank headquarters building. Architects Hugh Stubbins and W. Easley Hamner designed the church with Italian-born designers Lella and Massimo Vignelli consulting on the interiors.

The design of the Chapel was awarded to Louise Nevelson, who was by then renowned for her monochromatic sculptures that were sometimes black, sometimes white, and rarely gold. The pews and architectural elements of the Chapel, also designed by the Vignellis, extend the aesthetics of the larger church, with its soaring sanctuary and impressive pipe organ. Moving from the sanctuary of SPC into the Nevelson Chapel, is to move from grandeur into elegance; there is no rupture, only a continuous aesthetic language that carries the visitor through the space.

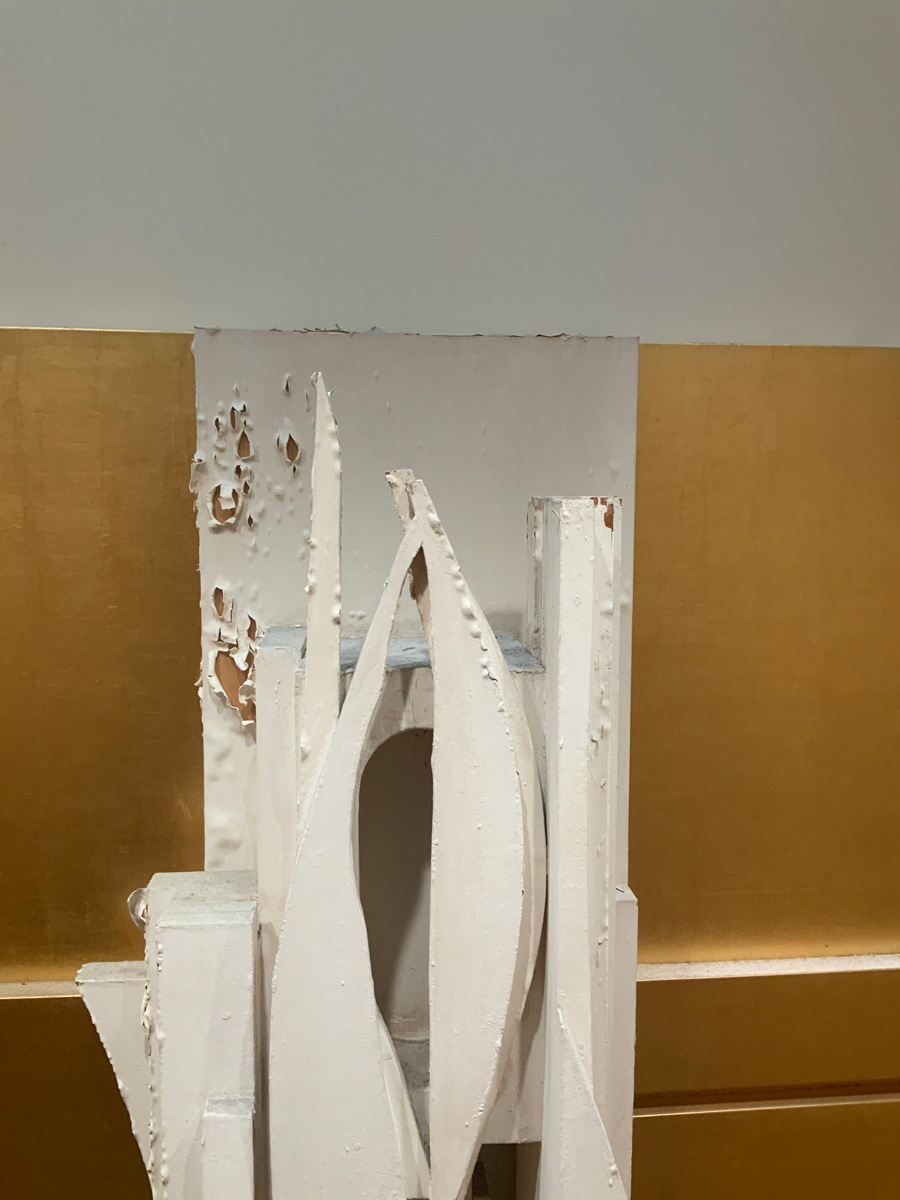

The Chapel is one of Nevelson’s most powerful creations. Stepping inside the Chapel feels like entering a sculptural jewel box. The space is intimate and modest in size, about 28 by 21 feet and roughly five-sided, seating around 25 people. Surrounding the visitor are five large wooden sculptural assemblages anchored to each wall. A group of suspended sculptures add some movement. Made from irregular pieces of cut wood and plywood, the works are painted white, except for the centerpiece, The Cross of the Good Shepherd, where a bold white abstract form stands out against a radiant gilded background. The Nevelson Chapel is the only one of the artist’s immersive environments to remain in situ and intact.

With its striking architectural and artistic elements, the Church and its Chapel have become a revered cultural destination. The Chapel offers a serene refuge within Manhattan’s urban setting for meditation and provides an intimate space for worship within SPC. As one of only a handful of permanent public installations by Nevelson, the Chapel stands as a landmark of twentieth-century American art as much as of faith.1 Today, SPC continues to ensure that the Chapel remains open daily and accessible to all.

Yet such distinction proved fragile. The need for conservation at the Chapel emerged early. In the 1980s, the Church occasionally engaged someone to “touch up” the sculptures. Campaigns to clean and restore the sculptures occurred in the early 2000s, then a more intense professional restoration effort was undertaken from 2014-2019. For the first efforts, records were not made and oversight was minimal. Later restoration efforts were little better documented. This lack of documentation and management highlights the informal nature of the early restoration, which may be typical of collections managed by non-specialists.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when SPC was empty and staff were working remotely, the sculptural elements in the Nevelson Chapel suffered major damage. A failure in the HVAC system undermined the stability of the paint on the sculptures, prompting the Church to bring in a team of conservators to assess the situation and begin the careful work of examining, documenting, and treating the sculptural environment. Guiding this effort was the Arts Committee of the Nevelson Legacy Council, which played a central role in overseeing the project. As we write this article, all sculptures that were damaged by the HVAC failure have received conservation treatment, although it is not yet concluded.

It is challenging for communities or stakeholders who oversee the care of public or sacred artworks, especially when community members have no formal training in the preservation of cultural heritage. By exploring the historical trajectory of restoration at the Chapel and considering how earlier efforts informed later decisions, we will trace how the collaboration between the Arts Committee and conservators guided restoration efforts, supporting long-term stewardship of the Chapel and offering insights to others working in similar conditions. To do so, we will draw on interviews with members of the Arts Committee and conservators. They include the voices of the conservators (Martha Singer and Jean Dommermuth) and the Arts Committee at Saint Peter’s Church (SPC) who, at the time of this writing, are:

Jim Boorstein, Founding Principal of Traditional Line Ltd., an architectural conservation firm;

David Hottenroth, Founding Principal Architect of Hottenroth + Joseph Architects, SPC member;

Kate Lewis, Agnes Gund Chief Conservator of the Museum of Modern Art’s David Booth Conservation Center and Department;

The Rev. Jared R. Stahler, Senior Pastor, SPC;

Anne Umland, Retired, The Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture, the Museum of Modern Art

Karen Zukowski, Chair of Arts Committee, Historian and curator of artists’ environments, including Olana State Historic Site.

Their comments have been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

The Arts Committee emerged as an outgrowth of the Nevelson Legacy Council, which was headed by David Diamond (Principal and Consultant, David Diamond Associates) and Jared Stahler (Senior Pastor, SPC), and was established around 2017 as the primary fundraising body dedicated to preserving the Nevelson Chapel. However, when it came to making aesthetic decisions, Council members were aware of the need for more expertise.

David Hottenroth: It started by us [members of the Church] beginning to think about how we would go about restoring the Chapel and realizing that before we spend time and money on the pieces, we need to take care of the environment. This started 10 years ago. We consulted many people connected to the art world who cared about the Chapel, even beyond the Saint Peter’s community. Since we didn’t know how to proceed, it took time to figure things out. Jared Stahler, who has strong art-world connections, began reaching out widely and asking questions about how to move forward.

Jared Stahler: At the earliest stages there was knowledge from the Church’s perspective that an employed conservator would be important. But as the project went on and as decisions needed to be made – about every aspect from lighting to architectural aspects to how would we accommodate this HVAC system, – those elements led us to say, we need others, because it was becoming a dialogue between the conservator and us, members or employees of the Church. And there were no other voices involved. That’s when we started to open up the conversation about what should be happening.

As the Church is the main stakeholder in the Chapel, how does the Arts Committee fit into the Church’s larger structure?

Stahler: Our constitution allows committees to be formed where certain committees have members from outside the community as kind of advisory. And the Nevelson Legacy Council was established in that way. But that council was not tasked with the conservation. It was more programming and fundraising. In the Church, there are continuing resolutions now. This gives the committee a tremendous amount of oversight. David [Hottenroth] and I are the only two official members of Saint Peter’s who are on this committee. The Parish Council has authorized that in a very intentional way. Those continuing resolutions are debated and adopted annually. The parish council thinks very highly of all the people on this Arts Committee.

Therefore, the evolution of the Arts Committee did not follow a formal process but was built through personal connections. From the Nevelson Legacy Council (the fundraising committee), came Karen Zukowski and Anne Umland. Karen Zukowski is married to David Diamond, and Umland had known both of them since all three attended college together. These interpersonal relationships contributed to a heightened sense of trust and openness among committee members.

The Arts Committee recognized the importance of establishing foundations of trust and transparency within the overall process.

Hottenroth: Asking for reports and documentation was very helpful information from Karen because, as clients, we didn’t know that was something that we could expect or that we could have much input in the conservation process.

Stahler: As we broadened the number of people who were discerning a way forward of the Chapel, it became clear to us that we needed to work with conservators who were prepared to have that wider conversation. And so that was something that with Karen’s leadership, the Church led.

Kate Lewis: This is a conservation project and it’s a community project… I joined the committee the moment that the temperature and relative humidity issue happened, and then was part of, with you [conservators] thinking through – how do we start working through the bigger questions that evolved as a result of that breakdown in the HVAC?

James Boorstein: I think an important part was that Jared, the main person, was deeply involved and connected and interested in the issues. It is rare and refreshing to work on a project where the team focuses on issues of the work – how it should be approached and accomplished ahead of budget and deadlines.

Thus, the Arts Committee became more diverse in two respects: it encompassed a range of arts backgrounds, and it included both members and non-members of the SPC community.

Conservation at the Chapel has always been a layered story, with two prongs of conservation happening simultaneously. The primary conservation focuses on the restoration and the second focuses on environmental controls. There were at least three campaigns of conservation at the Chapel before the HVAC failure. First, there was the original restorer from the 1980s. Next, in 2004, New York University graduate students carried out basic cleaning and consolidation. Then, from 2014-2019, SPC hired Sarah Nunberg. During this time, the environment was evaluated, revealing that it needed to be stabilized.

When the Church was built as part of the larger Citicorp building, a single HVAC system controlled the environment of the Church and the entire 59-story office building. However, museums and office buildings do not have the same HVAC goals. Office systems are designed to keep people comfortable while museums or collection spaces require a narrower range of relative humidity and temperature for the art. Therefore, it is unsurprising that environmental monitoring in the Chapel revealed that the relative humidity fluctuated between 6% and 84%.

In 2018, the Chapel was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to separate the Chapel’s environmental controls from those of the larger office building. However, this initiative resulted in only a partial separation of the Chapel’s environmental controls from Citicorp.

When the HVAC failed in 2020, the Arts Committee had to hire a conservator for documentation and emergency treatment. From conservators in New York City, they chose Martha Singer, a sculpture conservator who had asked Jean Dommermuth, a paintings conservator, to join her. Although the Chapel is considered a sculptural environment, the extreme paint blisters and flaking paint on Nevelson’s sculptures were outside her area of expertise and she felt that having a partner like Jean Dommermuth, who specializes in the conservation of painting and painted surfaces, would make their team well-rounded.

Dommermuth: Working with any client, whether it’s an individual, or a committee, or a corporation – that client has their own personality, and their own priorities… I feel like that as the conservator, you come in, and you have to get into that point of view, whatever it is.

The most recent conservation campaign emerged in response to the HVAC failure, a moment that forced both crisis management and long-term planning.

The first challenge was to stabilize the sculptures themselves. Immediately after the HVAC incident, the conservators documented the Chapel’s condition and suggested a treatment plan for an insurance claim. The conservation progressed very slowly during this period because several discussions were needed with the insurance company.

What was our decision-making framework as a committee?

Boorstein: I did find that, for the most part, it was a consensus system, which fits well with my Quaker background.

Lewis: There was this catastrophic failure of the HVAC. But in a way there was a silver lining because although it was upsetting, and it changed that work fundamentally, it meant there was insurance money. We were going to move forward. Because it was such a massive project [the insurance] slowed us down so that we had time to take stock and think through these different steps. I think this extra time helped with those different discussions, some of which were difficult and complicated.

The conservation treatment took on an iterative approach, adopted in part because of the insurance claim, the Church’s liturgical calendar, and the availability of private conservators. The composition of the sculptural environment facilitated this, as each of the individual sculptures could be treated in turn. Treatments and tests were conducted in stages, with periodic meetings that allowed committee members to observe progress, offer feedback on aesthetic outcomes, contribute contextual knowledge, and engage in dialogue about the broader implications of the treatment. These sessions proved invaluable, serving not only as decision-making checkpoints but also as forums for rich historical and communal exchanges. Meeting discussions brought to light practical and historical details and touched on the Chapel’s history and the role of the SPC community. This included Nevelson’s influence upon the Chapel’s design, materials, and practices. At the outset, the conservators advocated for scientific analysis when filing with the insurance company to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the paint’s composition and the mechanisms underlying its degradation, expecting that it would aid in selecting an appropriate treatment.

Zukowski: …the process of deciding to do the chemistry testing was expensive, and the committee took a leap of faith to decide it was necessary to conservation work. An interesting dynamic.

Ultimately, the science did not change the treatment, but it shifted the committee’s understanding of the paint layers and further underlined the need to maintain a stable environment.

The committee decided that, due to the extreme damage to the Cross of the Good Shepherd, the focal point of the sculptural environment, conservation should start there. The treatment of that sculpture was deliberately conservative, understanding that it would be revisited after other sculptures were stabilized. When the committee viewed the results, there was indeed agreement that treatments might be taken further in terms of reintegration.

Stahler: In the pandemic, when people weren’t even in the building, our sense of time was skewed. While we were taking time in conversation, other people who were not involved in those conversations, seemed to have a level of impatience with the idea of time, and thinking through the complexity. That taking of time and committee reflection, that was a learning curve for a number of people, both inside and outside of the Church.

Singer: How our group works—I see it as a lot of back-and-forth discussion. One of the most important parts of the project is the pause. We stop and think as we have to write a report for you, tell you what we’re doing [and experiencing]. This pause also gave us [conservators] time to reflect on what we’re doing. And, in reviewing our work, we realized what we had learned.

At the same time, the environment had to be stabilized. What became apparent is that the environment controls installed in 2018 were still dependent upon the office building for chilled and hot water. So, when offices shut down during the pandemic, the Chapel lost necessary inputs to its system. The humidity in the Chapel spiked and air was blowing strongly.

Currently, there is an environmental subcommittee comprised of Hottenroth, Boorstein, along with Stahler, Singer, and representatives from the building engineering and maintenance teams. This subcommittee has worked to ensure the effective operation of the HVAC system. Their efforts have included coordinating with various engineering consultants to maintain optimal environmental conditions. Key initiatives have involved sealing the space as thoroughly as possible and implementing a comprehensive monitoring system. Singer tracks the environment daily, while software engineers have developed alert systems that provide real-time notifications of anomalies. Additionally, a routine monthly maintenance schedule has been established.

Just as important as the treatments themselves was the act of documentation: reports, photographs, and records that would ensure transparency and preserve memory for the future. Conventionally, such documentation is produced at the treatment’s conclusion. In this case, the conservators prepared reports throughout the project, detailing adhesives and the progression of different treatment phases. The six sculptures in the Chapel have different histories, and each needs to be conserved, and at the same time, become an integrated whole. This approach to documentation reflects the conservators’ commitment to transparency, allowing for periodic updates to the Arts Committee and for conservators to receive input from the Arts Committee, ensuring that the experience of seeing the whole is not getting lost in the process.

The agendas and meeting minutes created by Karen Zukowski, represent a significant contribution. These documents capture the individual and collective decision-making processes as well as offer valuable insight into the rationale behind treatment choices and broader interpretive considerations.

Karen Zukowski: I felt that documentation was important. We’re going to be able to leave a record of what’s happening and how we make decisions. And I want that to keep happening. So my pragmatic question is, where do all those records live? Like in 50 years where will the archives live so that future conservators and community members can go back to see what decisions were made and why…

Stahler: The Church has a Dropbox…where different things are archived, one of which is Chapel material…we just began thinking about whether or not it’s time for us to move our material from this Dropbox to a Google work platform, not only for the Chapel, but the whole Church…And one of the reasons for that is we know that Google has a lot more capacity for collaboration and transparency about who’s seeing what or who is editing what or who has access to what.

Following the reopening of SPC after the COVID-19 shutdown, conservation efforts continued alongside the active use of the Chapel, which allowed conservators to engage with visitors.

Umland asked the conservators if they had ever worked in public spaces. While both had, this was different, as it positioned them as individuals familiar with the daily rhythms of the space, and available to engage with visitors who had questions. Through these interactions, they gained valuable insights into the diverse interpretations of the Chapel’s iconography. For instance, a couple from Canada described seeing in Sky Vestment “la main de Dieu” (the hand of God).

As theologian John Dillenberger observed:

“Louise Nevelson has created many walls, and her sculptures grace many spaces. This meditation chapel, however, is the only work in which she had the opportunity to form the total environmental ambience… One is surrounded by her arresting, symbolic creations, true to the inheritance of the theological tradition, but freed of the iconographic literalness.”2

During installation, W. Easly Hamner, architect, (left) speaks with Louise Nevelson (right), 1977

Courtesy of Saint Peter’s Church Archives, New York

Anne Richter, an artist who visited multiple times said:

“The Louise Nevelson Chapel offers me the thrill of discovery and rediscovery. This is my reward for years and years of careful looking. I look forward to my next visit.”3

Dommermuth: This contained space was still in use, so there was our friend who came many days to meditate… There were people who would just come and hang out… There was something about the space that made it much more communicative than other projects that I’ve done in public, where you tend to be behind a barrier, and people are maybe just passing through. Something about the space itself makes it more interactive.

Thomas Bair, another visitor noted:

“It has become a daily refuge for me, literally, in the middle of Manhattan. My mood is calmed by being within the Chapel. Regular meditation helps bring this about, too. The Chapel is quiet and street sounds are barely audible.”4

Stahler: And a great gift to us that you were willing to engage with those people, and I think, over the course of the last several years. You’re reporting back on people’s engagement with the space was really informative to the whole committee.

Umland: I can say…a curator’s dream is to be the fly on the wall as people go through the galleries and hang out and talk to them and ask them, or have them talk to you. It was sort of built into your process—it makes the space come alive in a different way.

Umland described the Arts Committee as an “ecosystem,” emphasizing the interdependence of its members and the collective nature of their work. Each member playing a vital role in the success of the group, contributing expertise drawn from different professional backgrounds.

Boorstein: The work was to figure out what needed to be done, what were the possibilities, what was the best next step and then proceed with that.

Lewis: I feel like conservation’s really moved on. Now we really think about conservation: yes, there is material expertise, but that’s just one small part of the pie because you’re not necessarily the expert. The expert is the person who the work belongs to, or it is activated by all members of the community. Those are the people, you [the people in the community] are the experts in that piece of cultural heritage.

Stahler: Kate, when you were talking about conservation being a community effort, I think that I could say members of Saint Peter’s care about the Chapel and want it to be a place of worship. To be cared for and valued and enjoyed…this whole process has helped the congregation to see, “wow, others are also interested in this, others also care about it, and are committed to it.” There has been a wonderful growing level of trust between the congregation and this committee, which is to say between members of the Church and non-members of the Church. This committee is for me, like a little seed of something that I hope will only continue to grow. And this ever-widening community engagement. It has been a great gift to the Church… The more voices, the better.

As Anne Richter, an artist, reflected of her visit:

“I feel like Raphael when he looked into a rough hole in the ceiling of the Domus Aurea to discover a vigorous unknown style of ornate decoration. The Nevelson Chapel offers me that same sense of wonder each time.”5

Though intimate in scale, visitors frequently compared it to monumental sacred spaces. Thomas Bair says:

“While it really is small, it has a profound effect similar to gazing up into the high lofts of a cathedral; one has a feeling of wonder at the creative spirit lifted to God… To someone who has never seen the Chapel, I can say it is a stunning, artful environment that melds energy, excitement, and, contradictorily, peace.”6

In the end, the Nevelson Chapel is more than a case study in conservation. Nevelson herself remarked, “If people can have a moment of peace and carry it with them in their memory banks, then that will be a great success for me.”7 Her words underscore why stewardship of the Chapel matters. The preservation safeguards not only the physical sculpture, but also provides visitors space to reflect, and those memories will stay with them.

The Chapel is a living artwork, continually renewed by the people who encounter it. Louise Nevelson envisioned immersive environments that could transform perception; the Chapel remains one of her most powerful realizations. Its survival depends not only on careful stewardship by committees and conservators, but also on the recognition that its meaning lives in the responses it elicits. Preserving the Chapel is therefore preserving a shared cultural and spiritual heritage in the heart of New York City.

1. Saint Peter’s Church (including the Nevelson Chapel) have New York City landmark status since 2016 and will become eligible for designation on the National Register of Historic Places in 2027.

2. @nevelsonchapel, Instagram, August 22, 2025, https://www.instagram.com/p/DNqBR2Quws_/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

3. Anne Richter, email message to author, September 20, 2025.

4. Thomas Bair, email message to author, November 16, 2025.

5. Anne Richter, email message to author, September 20, 2025.

6. Thomas Bair, email message to author, November 16, 2025.

7. @nevelsonchapel, Instagram, August 30, 2025, https://www.instagram.com/p/DN_C6irEw3n/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Main image

The Erol Beker Chapel of the Good Shepherd, Photo by Marco Anelli (2023)

Image description

A photo of a brightly lit room with white walls, wooden benches, and a wood floor. On each wall are large-scale sculptural artworks, made of cut wood and plywood. The sculptures are painted white and feature a range of geometric shapes – some positioned one next to another, and some stacked or overlapping, creating depth and stark shadows. The artwork on the wall of the right side has a vertical stripe of white in the center, flanked by two gold-colored sides. In front of this artwork is a small wooden table. At center of the far wall is a window, revealing a narrow view to the outside.