Sound and Vision

Barbara London was a curator at The Museum of Modern Art for over forty years. During her tenure she pioneered research into artist books, sound art, and most notably video art. To this day she continues to curate, teach, and write about art that expands the canon and pushes new boundaries. She will publish a book titled Video/Art, The First Fifty Years with Phaidon press in 2020. In February 2019, Barbara London spoke with VoCA’s Kate Lewis about exhibiting, acquiring, and preserving video art.

Barbara London: Here I am, I’m Barbara London, the founding Curator of Video and Media at MoMA.

Kate Lewis: And that’s the reason why we’re talking today. So Barbara, when did you start working at MoMA and in what capacity?

London: Around ’71. I started out in the International Program, where I was a curatorial assistant to Jennifer Licht, who co-founded the “Projects” series with Kynaston McShine. I worked with Jennifer on Some Recent American Art, an exhibition that the International Program sent to Australia. Some Recent American Art featured sculpture by prominent young artists who made their names by challenging the definition of sculpture. A few of them had also experimented with video; therefore, we included tapes by Vito Acconci, Lynda Benglis, Robert Morris, Richard Serra, Keith Sonnier, and William Wegman. This selection became the first in the ongoing series of video exhibitions that MoMA established in 1974 with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. I often think that someone like Serra, and Benglis too, felt that video offered the freedom to explore and experiment while they were making their sculpture. Everybody gets boxed into a corner at some point. I think it was in the same way that Matisse got his hands dirty with clay and found it liberating to make sculpture. Similarly, I think in the early seventies video was a liberation for a number of artists actively working between disciplines. Many were working counter to matters at the time, such as the Vietnam War. Others were responding to the women’s movement. Video was kind of a clean slate for people to engage with. So Jennifer really encouraged me to run with this hot potato.

Lewis: So you started in the Print Department?

London: Yes, around that time Riva Castleman had offered me a curatorial position in the Print Department. The first thing I did was start the Artist Book Collection. To me artist books, which were offset and only cost a couple of dollars—such as Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations—were intended to get into the hands of anyone interested. This was similar to what was going on with video. The early artists, such as Nam June Paik and Martha Rosler, were utopianists and were about making work that wasn’t a precious commodity and could be seen by art school students. I saw a parallel between the artist book and video.

Lewis: In 1973 MoMA obtained a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to purchase a videocassette deck and two monitors. As a conservator I have to think about the practical side of things, so I am interested to hear more about how it actually happened.

London: Dick Palmer, then Head of the Exhibition Department with Riva Castleman who was then my boss in the Print Department, worked together with Development to request a grant from the NEA. They were of course delighted when the grant came through, but then who exactly was to program and use it? There I was, a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, young curatorial assistant, and they said: Barbara, run with it! So you ask the very pragmatic questions, and indeed it was tricky because in those early days we had no in-house production equipment. In my book that’s coming out in January 2020 with Phaidon, I mention that William Paley, the Chief Executive of Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), invited the two MoMA film projectionists and me to walk over to CBS’s studios, where we learned about the care and maintenance of our ¾-inch U-matic video cassette deck with an automatic rewind button. Of course the projectionists were better at operating the very crude and clunky equipment, but I was certainly capable of opening up the playback deck and taking the jammed tape out and attempt to fix it.

SONY BVU-800 U-matic Video Tape Recorder

Sony Co., Ltd. Photo by Mangos

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=436547

I commandeered production houses to help make what we called compilation reels. I always say that the ¾-inch cassette is what really made video art fly, given that most people were technophobes. Contemporary curators were technophobes, too. Nobody wanted to manually thread up an old open-reel ½-inch video machine. So every exhibition that I organized back then functioned with a ¾-inch cassette compilation reel. For each show, I selected the artists’ videos, which were then put consecutively on the cassette, which played on two monitors in the Video Gallery. Six days a week the projectionists turned the equipment on in the morning and turned it off in the evening. We always made at least two copies, one for exhibition, and a second for back-up.

As you can imagine, ’73 and ’74 was a very political time, and artists tended to be angry with powerful institutions. For some, MoMA, along with TV stations CBS and NBC were considered the enemy. So putting these video exhibitions together sometimes took a bit of doing.

There was very little information about video art at that point, so I learned by attending all kinds of screenings. If I got wind of something that was going on in an artist’s loft, I went, usually on the weekends and the evenings because in the beginning I still had my print responsibilities. Several things happened around 1975. I was still in the Print Department when we made our first acquisitions, which included Vertical Roll (1973) by Joan Jonas, Undertone (1972) by Vito Acconci, and Global Groove (1973) by Nam June Paik. Mrs. John D. Rockefeller III, former President of MoMA, was very supportive and she along with a couple of other people supported our request for funding. Back then a single channel videotape by Richard Serra or Martha Rosler would cost about $250, and the edition was unlimited. So what did I do? I took the newly acquired archival master video tape and, because I was in the Print Department, wrapped the cassette in glassine to protect it from dust, then shipped it off to the Film Department’s storage vault where temperature and humidity were relatively stable.

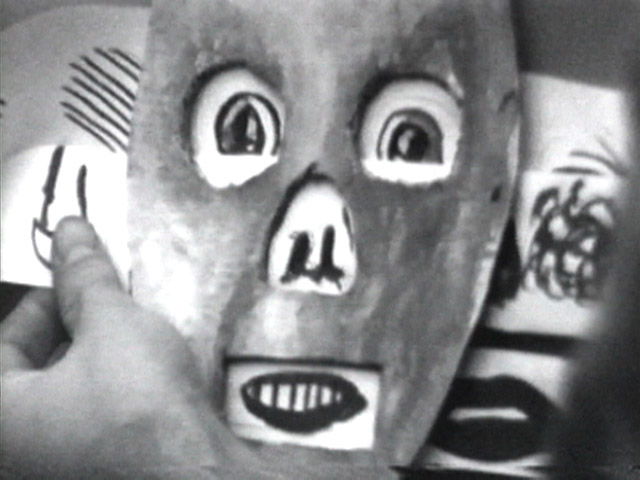

Joan Jonas, Vertical Roll, 1972

Video (black and white, sound), 19:38 minutes

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Barbara Pine, 1975

© 2019 Joan Jonas, Image courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

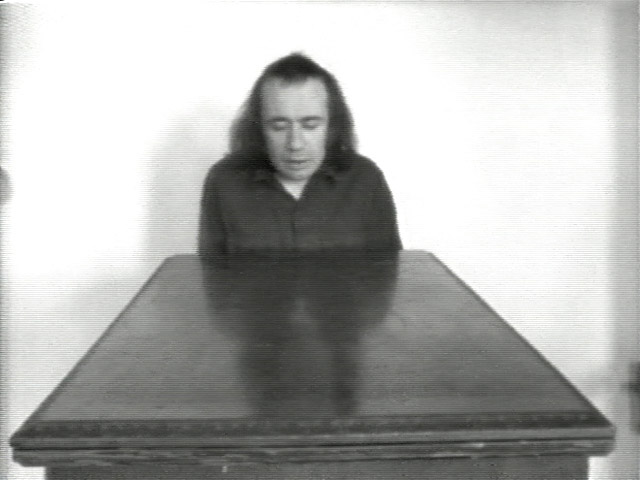

Vito Acconci, Undertone, 1973

Video (black and white, sound), 34:12 minutes

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Barbara Pine, 1975

© 2017 Vito Acconci, Image courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Lewis: You mention that there was very little written information about video art. How did you address that?

London: There was very little information in print, so every piece of paper that any artist gave me went into a file. I always had an intern, whose job was to organize and put these materials into what became the artist files that are now in the MoMA library. I also had files of alternative spaces, distributers, subject files, and then museums, because my colleagues like John Hanhardt at the Whitney, Kathy Rae Huffman at the Long Beach Museum, Dorine Mignot at the Stedelijk Museum, and Christine Van Assche at the Pompidou were also starting to program video. The ephemera was basically for my use, to be able to curate. I would have a bio for so-and-so who had come through last year, and now was about to program their work in a show. The interns were always upgrading the files, so within ten years I probably had filled six four-drawer filing cabinets. Ultimately the library took over this archive in 2010, and it was easy for them to take it because it had been so well organized.

Lewis: You wrote in The Brooklyn Rail about the curator traditionally wearing many hats including acquisition, conservation, research, and education. I was thinking specifically about conservation and read that for each acquisition you collected a preservation sub-master, an exhibition copy, and a study copy.

London: There was a moment when there was a work of Vito’s which I showed, Theme Song (1973). Amy Taubin, who was then at The Kitchen, and I realized that the video material Vito had was perhaps not in good shape, so we preserved the MoMA copy; this was my first video preservation project. Together with Mary Lee Bandy, former Director of the MoMA’s Film Department, we considered applying for a video preservation grant to do something for the field that would make sense. Tony Oursler, who had explored video while he was a student, visited me shortly after he graduated from Cal Arts. I knew that some of his early work needed attention, in particular his unusual feature length video, The Life of Phillis (1979). That became part of our NEA video preservation grant. We also helped the Ant Farm and a number of other artists with the preservation of their early video works. We knew that many artists were storing videos in attics or their mothers’ garage. And there are always unexpected disasters that occur, such as the fire that destroyed the Ant Farm’s archive. It was clear that the Museum had to do something. Unfortunately you can’t do everything. You have start somewhere and hope you’re making the right decisions.

Lewis: So thinking about those early acquisitions, you mentioned Joan Jonas’s Vertical Roll (1972), which is very specifically about television technology, and was originally shown on a small cathode ray tube monitor. Later, it was projected at Columbus Circle. In your 2018 interview with her at Eyebeam, Joan said, “It was hard for me. A woman reviewed it in a newspaper and said it was the worst thing she ever saw.” And then you said, “It’s complicated making a work that’s intended for a particular scale.” Joan then said, “I think we’ve all relaxed. At the beginning we didn’t want these things to be projected, but then we relaxed because it was the only way to show this work to people.” So we’re talking about video, we’re talking about technology that changes rapidly. I mean we haven’t reached a point of absolute obsolescence, but in your forty-year career with these works, we’ve seen artists migrate works from the ’70s and ’80s. How do you feel about these types of alterations that slowly happen over time?

London: Well, I think either you do it or the work dies, and I don’t think anybody wants masterpieces to disappear. I was just at the Nauman show at PS1 this afternoon with a colleague who’s a writer, and we were looking at Nauman’s early video work. It’s all shown on monitors, and as with Joan’s, a monitor has the perfect intimate scale. It’s so reminiscent of television. The newscaster’s head appears as if it’s in a terrarium. I’ve had long conversations with Mary Lucier about her work. She knows that if her installations are so tied to old display technologies, her work may no longer be able to be shown. So she takes it on herself to figure out how to move her work forward so that it won’t die.

Lewis: You talk about how artists were really important collaborators as you developed the Video Arts position at MoMA. Can you talk about the series you initiated, Video Viewpoints?

London: Video Viewpoints had a counterpart, Cineprobe, initiated by the Film Department in ’68, a series in which experimental filmmakers screened their new work. I wanted artists I invited to participate in Video Viewpoints not only to show new work but also discuss their ideas behind how and why they approached their productions, which was important given how little information was around. I wanted artists to talk about the aesthetic and technical choices they had made. I wanted them to come uptown to MoMA to show new work and discuss their practice. The talking was very important. I had my interns transcribe these talks, and today most of the texts are in the library, along with the audio recordings.

Lewis: And we continue this practice of talking with artists and collecting oral histories, it’s very important for conservation. Could you tell us more about your book?

London: Well, it’s been a very interesting process. I left MoMA in 2013 and it took me quite a while to find my voice and be able to discuss the artists and their work in a way that was informative and provide a context. I’ve worked hard to do that. The book begins with a little backstory about how I started out in art history. It talks about Paik and my visits to his studio when he wore rubber boots so he didn’t get electrocuted! The book attempts to offer insights about an artist’s practice, and give something about why I gravitated towards work or why it interested me. For example, in the early 1970s, many artists lived in places with low rents, and in New York that happened to be what became known as SoHo; there artists and composers would run into each other on the street. One day Michael Snow told Joan Jonas, who then was the partner of Richard Serra, “Obviously, minimalism is not for you. You’ve got to go see Jack Smith.” So she did. That moment opened up a whole other way of working for Joan. These insights are what’s of interest to me.

What else? There’s the show I did called Music Video: The Industry and Its Fringes in 1985. My decision was to show work that was pushing the envelope, not just MTV promos, but work where there was a real connection between the musician and the visual artist. Fortuitously I managed to get all of the selected music videos into the collection. The forty or so videos were assembled onto two archivally sound one inch submasters at the J. Walter Thompson production house, through a congenial video editor. My selection included David Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes (1980), directed and produced by David Mallet and David Bowie. Interestingly fifteen years later I got a call from Mr. Bowie’s office. The person said, “Oh, we just found a letter that you wrote Mr. Bowie. Did you ever receive the archival sub master?” I said, “Yes, and I’d be happy to mail you the press release, which I had initially sent.” I didn’t want the person to get off the phone, so quickly said, “I don’t know if Mr. Bowie would be interested in donating all of his music videos, but we would be delighted if he did.” They called me back a day later and said yes! So I was always just trying to figure out how to segue one thing into another, help things expand, and grow my own knowledge.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HyMm4rJemtI%5D

Lewis: Can you talk about the shift from video works shown on compilation tapes to video installation works, and specifically your 1995 exhibition?

London: I had already organized several “Projects” exhibitions with video installation artists. I did a Campus show in ’76, and initially experienced resistance to these works becoming acquisitions. Around that time, video had become part of the Film Department, but everyone was cautious about video. Acquiring Campus’s installation proved impossible. William Rubin followed the Alfred Barr idea of not acquiring something until five or six years had passed. Now that competition was getting fierce around contemporary acquisition, it meant another museum might snap up a great work. For example, when I curated Paik’s TV Buddha in a Projects show, the Stedelijk quickly acquired it. I had people like Mrs. Rockefeller, Agnes Gund, and others who were very supportive of video, so I just bided my time. I tried to be polite, as I gently tried to nurture video along within the Museum. In 1981 MoMA acquired Shigeko Kubota’s Duchampiana: Nude Descending a Staircase (1976), a gift from Margot and John Ernst, Agnes Gund and Barbara Pine, but it had to come in through the Department of Painting and Sculpture because it was sculpture.

Shigeko Kubota, Duchampiana: Nude Descending a Staircase, 1976

Super 8mm film transferred to video and color-synthesized video (color, silent), monitors, and plywood, 66 1/4 x 30 15/16 x 67 in.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Margot and John Ernst, Agnes Gund, and Barbara Pine. © 2019 Shigeko Kubota. Digital image © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Photo: Thomas Griesel

Lewis: In addition to video and artist books you were also an early promoter of sound art.

London: In 1979 I wanted to do a sound show, and MoMA said, “Hm-mm, it’s not visual.” So I did it in the little video gallery. I included the work of three great artists—Connie Beckley, Julia Heyward, and Maggie Payne. What did I call the show? Sound Art. You know, it may appear a simple title, but it’s what it was.

Lewis: I’ve heard you use the term “hot potato.” What do you think is the next hot potato?

London: Well there’s UUmwelt (2018), an installation that Pierre Huyghe made and premiered at the Serpentine Galleries in London last year. He worked with an infomatics lab in Kyoto, where he was able to capture images from the brainwaves of someone who had been asked to imagine a situation. I think this type of technology is interesting. Visitors ambling through the Serpentine encountered five enormous LED screens, dust on the floor, and flies everywhere, in the air as well as dead on the floor. Depending upon the live flies’ and the visitors’ motion, the strange images would shift slightly. I was quite taken by the visuals and the sound, which was derived from sounds the brain makes. The visitor was walking into a nether-land. Pierre is an intelligent, interesting artist who consistently pushes the envelope. There are some things that will emerge from new kinds of infomatics. I believe there’ll be headsets like headbands, rather than one having to use an MRI, and artists will be moving in new directions. Still for me the bottom line remains the same—a great work revolves around ideas and the poetry in the artist’s voice. The tools, new or old, play second fiddle.

Lewis: Your book comes out this January, what’s next?

London: A book tour in cities where I will be in dialogue with an artist from that location, which I feel is very important. The other thing I’m involved with is the organization of a sound exhibition, which Independent Curators International will circulate. Seeing Sound will have sonic sculptures that are basically performable. The idea is that at every venue there will be a performance. The artists include Marina Rosenfeld, whose work opened last night at Hunter College’s Artists Institute Gallery. Most likely the show will start on a small scale in June, when we will trial balloon certain new technologies. It’s always important to know your software and your hardware in advance.

Lewis: The technology testing mantra must be second nature after forty years

London: Yes, I learned the hard way!

Further reading

Glueck, Grace “Videotape Replaces Canvas for Artists Who Use TV Technology in New Way. April 14, 1975

https://www.nytimes.com/1975/04/14/archives/videotape-replaces-canvas-for-artists-who-use-tv-technology-in-new.html. Accessed March 5, 2019