Rewind

A Brief History of Caring for Video Art in the United States

In 1993, the Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC), under the leadership of Sally Jo Fifer, embarked on a three-year mission to develop best practices for video preservation. This project would lay the foundation for time-based media conservation.

Faced with the need to re-master ½” open-reel video, the earliest portable tape format, BAVC struggled to understand the complexities of preserving the material. The ½” open-reel format, initially introduced with the Sony Portapak in 1965, was the first video format used by artists and activists and was common from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. Due to rapid technological advances, a lack of standardization, and general degradation, people began to worry that action needed to be taken soon to preserve the important artwork and documentation held on these tapes.1 With this in mind, BAVC brought “together a diverse group of professionals including distinguished conservators, scientists, video artists, media curators and television engineers to undertake the challenge of preserving the hundreds of thousands of hours of cultural and artistic history recorded on videotape.”2

The decision to gather a varied collection of experts who were just beginning to grapple with the long-term preservation of analog video was momentous and culminated in 1996 in the two-day symposium Playback, held at SFMOMA. Mona Jimenez, affiliated with Media Alliance in New York, worked with BAVC to bring new voices into the mix, notably conservators Debbie Hess Norris and Paul Messier, both formidable talents in the conservation field. Debbie applied established conservation ethics to the care and preservation of video material, while Paul laid the groundwork to bring this relatively new creative medium firmly into the conservation field. With the inclusion of conservators, this symposium spurred active engagement in the conservation not only of video, but also time-based media art writ large. Looking back at this moment and the tremendous work and discourse it facilitated, one can see that time-based media—and video specifically—has been cared for by a constellation of individuals and organizations, each playing their own role to establish it as a legitimate art form that requires the same status and care as painting and sculpture.

On October 4th, 1965, as the story goes, Nam June Paik got his hands on one of the first Sony Portapak ½” open-reel video cameras, charged the batteries, shot footage of Pope Paul IV from a taxi cab, then went straight to the Cafe Go-Go gallery and screened it. Despite the apocryphal nature of the story (the Sony CV-2400, which allowed for portable taping, wasn’t released in the US until 1967), this is regarded by many as the birth of video art.3 The mid-1960s saw artists begin to experiment with video, culminating in the legendary exhibition TV as a Creative Medium at the Howard Wise Gallery, widely considered one of the first exhibitions centered around the artistic possibilities of television and video. Paik, in collaboration with the groundbreaking Charlotte Mormon, were some of the many artists exhibiting their new work on video and cementing their status as the founders of video art. Also in the show were two young Marshall McLuhan acolytes, Ira Schneider and Frank Gillette, showing their video installation Wipe Cycle. The work consisted of nine monitors which displayed synchronized cycle patterns of live and delayed feedback, broadcast television, and taped programming shot by the artists. Both were eager aficionados of video and wanted to experiment and further engage with the emerging community surrounding and supporting it. Inspired by this desire to collaborate, in 1969 Gillette would go on to form the Raindance Corporation with Paul Ryan, Michael Shamberg, Louis Jaffe, and Marco Vassi. An ironic nod to the Orwellian Rand Corporation,4 Raindance was founded as “an alternative media think tank; a source of ideas, publications, videotapes, and energy providing a theoretical basis for implementing communication tools in the project of social change.”5

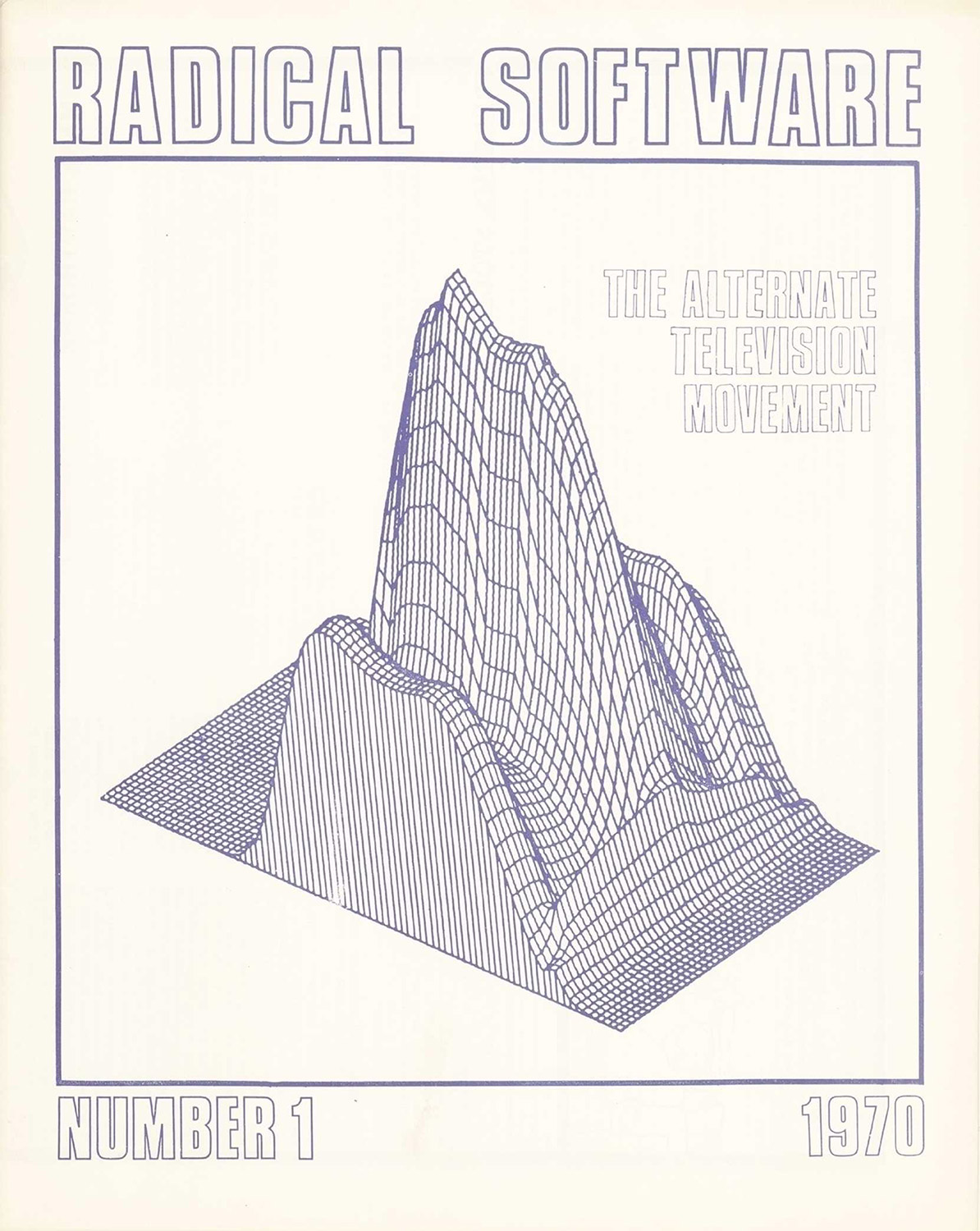

The Raindance Corporation was one of many video collectives popping up around the nation: The Videofreex (Catskill Mountains, NY), Ant Farm (Bay Area, CA), and Optic Nerve (San Francisco, CA), among others. Central to each of their formations was the possibility of television and video as means of an artistic expression that allowed for new forms of distribution and access. Shamberg, co-founder of Raindance and later TVTV, strived for a “Do-It-Yourself” ethos that reverberated within many of these collectives. Part of this ethos was the community-oriented practice of skills and resource sharing. Video was an exciting medium; the technology was rapidly developing and evolving. In an effort to capture and disseminate these changes, many of these collectives published “how-to” guides and resource listings. The Videofreex published the landmark Spaghetti City Video Manual: A Guide to Use, Repair and Maintenance in 1973, which sought to put the power of the medium into the people’s hands and artfully illustrated the video production process. Prior to this, the Raindance Corporation began publishing the periodical Radical Software in 1970. Edited by Beryl Korot and Phyllis Gershuny, Radical Software aimed to not only circulate information about this new televisual medium but also build and shape the community around it. As the first issue states:

Some of us who have been working in videotape got the idea for an information source which would bring together people who were already making their own television, attempt to turn on others to the idea as a means of social change and exchange, and serve as an introduction to an evolving handbook of technology.6

Radical Software was a galvanizing publication, and became an incredibly important place to share information about the rapidly changing medium. Korot, working with Ira Schneider, originally wanted to publish at least six times a year, feeling that the changes in the technology were outpacing their ability to document them. Korot and Schneider would drive across the country distributing Radical Software, hoping to turn on and connect like-minded video heads. In the second issue, one can already see discussion around standardization, something that was just starting to emerge in the video industry thanks to the Electronic Industries Association of Japan (EAIJ)’s introduction of the AV format for the ½” Portapak system.7 Eric Siegel, who designed a video synthesizer used for his piece Psychedelavision in Color—shown in the Howard Wise show—made the case for artists to use this new EAIJ standard: “The major thing holding us back is the lack of exchangeability of tapes among ourselves. If we all agree on one system and get other people to join us on the same system, we could start what we have to do.” If everyone agreed on one format, the exchange of tapes would become easier and distribution channels could be solidly built.8 Amid the conversations about building a new community around video, artists were also having practical discussions about how to allow for easier distribution and access to this material. While not explicitly stated, preservation concerns were roiling under the surface as this new artistic practice was taking shape.

Sustaining the publication of Radical Software became burdensome for the young video artists, both in terms of time and funding, so in stepped the newly formed New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA). Formed in 1960 by then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller, NYSCA’s media division began funding largely film-related events, including programs and symposia held in conjunction with Experiments in Arts and Technology (EAT). In 1969, their film program was formally changed to “TV/Film,” then “Film and Media,” with funding specifically allocated to support the burgeoning video scene. Grants went to Videofreex, Raindance, and The Experimental Television Center (ETC) to support their groundbreaking activities in the media of television and video. NYSCA would go on to fund the development of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), founded out of the ashes of Howard Wise’s shuttered gallery, so that emerging video artists could develop their craft with access to the newest technology. EAI quickly shifted from being a purely production-oriented enterprise by starting a distribution arm, first distributing the works of a core group of artists and then expanding to become one of the preeminent video distribution services in the world.

Slightly preceding the establishment of NYSCA’s media division was the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, which also helped to nurture this artistic scene. The Rockefeller Foundation, under the direction of Howard Klein (an experimental musician turned philanthropist), realized the creative potential in this burgeoning technology. One of his first grants was in 1965 to Nam June Paik, giving him a living wage which enabled him to stay in the United States and write his critical essay “Expanded Education for the Paper-Less Society” (published in the first issue of Radical Software). NYSCA and the Rockefeller Foundation are largely responsible for providing critical funding to the already established video community, resources that allowed video to flourish as a creative medium and set the stage for its later care and preservation.

Open Circuits: An International Conference on the Future of Television, held at MoMA, and NYSCA’s Whitney Video Conference at the Whitney Museum, both in 1974, helped to make the case for television and video as creative, artistic media. As a result, in 1975 MoMA received support from the Rockefeller Foundation to acquire its first two video works: Vertical Roll by Joan Jonas and Global Grove by Nam June Paik. The funds were also used to purchase equipment to exhibit this material in MoMA’s galleries, first as part of the Projects series and then in Video Viewpoints, an ongoing exhibition program formed in the late 1970s. This equipment was so novel that curator Barbara London had to go to CBS after-hours with MoMA A/V technicians to learn how to clean the tape decks.9

Illustration accompanying Amy Greenfield’s article “The Case of the Vanishing Videotape”

Illustrated by Leslie Dunlap. Originally published in American Film, Volume 6, July/August 1981. p.17.

In the 1980s, video had a solid twenty years under its belt and more institutions were bringing it into their collections. There was now an institutional interest in revisiting and preserving the first works on tape in order to safeguard the medium’s beginnings. Because of the different standards in playback, technological fragility of the equipment, and age of the tapes, there was concern for how these pioneering works could be exhibited in the future. Looking to the broadcast industry for guidance, many seized on the idea of migrating video from format to format to keep the ephemeral signal accessible. For example, migrating the original ½” open-reel tapes to the more robust, and higher resolution, 1” format. Artists shared tips on how to play back older formats and how to migrate them in articles such as Amy Greenfield’s “The Case of the Vanishing Videotape”10 or Tony Conrad’s “how-to” guide on ½” open-reel playback and migration published in The Independent.11 Institutions also began to look toward actively preserving this material in their collections, with MoMA and other museums collaborating with various organizations to migrate their material and establish formal acquisition guidelines. For example, the requirement for acquisition began to stipulate a high resolution, master format be provided. Similarly, in 1986, thanks to NYSCA funding, EAI established their Preservation Program to research how best to care for and preserve the material that seemed most at risk.

A key example of the emerging anxiety over degradation and loss is Vito Acconci’s Theme Song. Made in Italy in 1975 as a part of ART/TAPES/22, Theme Song is a seminal work and an early instance of an artist exploring the intimate aspects of video. The piece circulated for a time until, in the 1980s, it was discovered that no suitable master material existed and the only extant copy was a PAL¾” U-matic tape held in MoMA’s collection.12 Thanks to the foresight of Barbara London and the collection care staff at MoMA, the tape was kept in the temperature- and humidity-controlled storage of the museum. Recognizing the importance of this work, and the extremely fragile state it was in, MoMA, in collaboration with The Kitchen, migrated the PAL U-matic to 1” Type C (which was a best practice at the time for master material) in both PAL and NTSC. This 1” tape would go on to be duplicated and deposited at EAI and is now considered the master material from which all subsequent copies have been derived.

Media Alliance, a nonprofit media arts membership organization operating in New York City, was directly concerned with the preservation of video. They convened the first Symposium on Video Preservation at MoMA in 1991. Attended by artists, curators, engineers, and collection care staff from museums and organizations nationwide (including the Pacific Film Archive and the Metropolitan Museum of Art), this symposium laid the foundation for future video preservation efforts. The resulting publication, “Video Preservation: Securing the Future of the Past,” was a critical resource that addressed the unique needs of this deteriorating medium.13 Mona Jimenez, one attendee of the conference, working under the auspices of Media Alliance, linked organizations in New York together to share resources, knowledge, and skills related to video. She then spread this network nationally, resulting in the collaboration with BAVC in the early 1990s that led to the Playback symposium in 1996.

Everything seemed to coalesce at Playback. Ideas were shared that formed the beginnings of time-based media conservation as a formal discipline. The publication of Playback: A Preservation Primer for Video, with a pivotal essay by Mark Roosa entitled “Maintaining Technology-Based Installation Art,” would carry these ideas forward. With this primer as a guide, many new video-focused associations and meetings were put together: the Electronic Media Group (EMG), a formal specialty group of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) founded by Paul Messier; Independent Media Arts Preservation (IMAP), born from Mona Jimenez’s Media Alliance; and the 2000 symposium TechArchaelogy.

TechArchaelogy was a truly groundbreaking symposium and helped to kickstart the burgeoning field of time-based media conservation. At SFMOMA’s Seeing Time exhibition earlier in the year, a group of specialists (conservators, registrars, A/V engineers, exhibition designers, curators, and artists) worked with a selection of installations in the show as case studies to develop a methodology for their care. Artists such as James Coleman, Gary Hill, Vito Acconci, Steve McQueen, and Dara Birnbaum were heavily involved and active partners. The results of this tremendous work were presented at the symposium and a publication of case studies and white papers came out in 2002.

Dara Birnbaum, Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission, 1990

Five-channel color video, four-channel stereo sound, surveillance switcher and custom-designed support system, Dimensions variable

Installation view at S.M.A.K.- Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent, 2009

Courtesy of the Artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris / London

Photo credit and Copyright: Dara Birnbaum

Serving as one of the case studies, Birnbaum’s work, Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission (1990), is a five-channel video installation, which provides an in-depth view of the student and worker occupation of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989 using satellite-transmitted imagery, cablecast-TV, and broadcasted reports for its imagery. The working group endeavored to document all aspects of the installation: the screens used, the laserdisc playback devices, the custom-built armatures, and aspects of the environment such as light and sound. In his 2002 article documenting the working group’s findings, Messier describes the risks the group addressed, notably format, hardware obsolescence, and degradation. Beyond these technological concerns, he articulates one critical piece of information that was missing:

Still lacking, however, is a document that spells out Birnbaum’s specific requirements for the composition and parameters for acceptable change when components fail. Without such guidance, any required change could result in perceived or actual degradation of the artistic intent. A centralized, accessible, and authoritative repository of technical specifications, measurements, materials, installation photographs, installation history, and correspondence pertaining to the piece does not exist. Assembly of this type of information will be increasingly valuable for future installations.14

This advocacy for the artist’s voice in the documentation, and the establishment of a central record for information pertaining to the work, is one of the most critical aspects of the care of media and contemporary art.

Dara Birnbaum, PM Magazine, 1982

Four-channel video (color, three channels of stereo sound; 6:30 min.), two chromogenic prints, Speed Rail® structural support system, aluminum trim, one wall painted Chroma Key Blue, and one wall painted red, Dimensions variable

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired with support from The Modern Women’s Fund and The Contemporary Arts Council of The Museum of Modern Art, through the generosity of Ahmet Kocabiyik and Jill and Peter Kraus, and with Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds.

© 2018 Dara Birnbaum, Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris

Digital image © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

Jumping roughly a decade ahead, another work by Dara entered MoMA’s collection: the four-channel video installation PM Magazine. First exhibited at Documenta 7 in 1982, the work has existed in various iterations with numerous methods of display throughout its thirty-year life. Using established procedures and protocols, largely developed from the work done at the TechArchaelogy symposium, the museum shepherded the installation into its collection. Conservation and curatorial staff interviewed the artist prior to acquisition to better understand the parameters of the work, its constituent parts, and its significant properties. Care was taken to analyze the past iterations and to get the artist’s thoughts on their success or failure and on how the museum should exhibit its edition in the future. Prior to acquisition, the artist’s master U-matic tapes were migrated to a digital file format for preservation and placed in secure digital storage. The work was catalogued and its condition assessed, technological dependencies were noted, and potential obsolescences were considered. All physical components of the work were thoroughly documented and stored with the utmost care. During its first exhibition, in MoMA’s Cut to Swipe, full documentation was made of the iteration and added to the institutional file for reference.15 This documentation lives in the museum’s ecosystem of knowledge for future colleagues and researchers to access so that the they can make informed decisions about its future life in the collection. These methods of acquisition, installation, and documentation can be directly traced back to that formative symposium in 2000.

Since then, there have been myriad developments in the time-based media field, from the increased collection of modern and contemporary media art to the establishment of media conservation departments at fine art collecting institutions. There continues to be fervent discussion about best practices of care for these works. At the AIC conference in 2017, the Electronic Media Group celebrated its twenty-year anniversary. In the room were conservators who helped found the group (Paul Messier, Glenn Wharton, and Joanna Phillips among others) with a new generation of media conservators, from a variety of backgrounds, whose numbers are only swelling. There are even new media-conservation training programs on the very near horizon.

This is by no means an exhaustive history of the many individuals and organizations involved in shaping the course of video’s maturation as an art form. Looking at how the video field developed through a combination of individual action, community-oriented collaboration, and governmental as well as philanthropic support, it is evident how video art was able to establish itself as an art form—without any one of these elements, the medium may have withered and died. Individuals tasked with the care of this material can look to this organic model for useful lessons: collaboration, dialogue, and access are instrumental when dealing with video material. It takes a collection of voices, beginning with the artist, and including gallerists, curators, and conservators, to create and care for this medium. As much as they did at the beginning, the dialogue of voices and exchange of ideas, both old and new, are necessary to further the exploration and preservation not only of video, but also of the works under the wider umbrella of time-based media, such as software, performance, and installation.

1 ½” open-reel tapes were not intended for long-term preservation. The format was originally introduced with competing standards, AV and CV, that were not compatible with each other and required dedicated playback decks. After open-reel was supplanted by a multitude of better, more robust formats such as U-matic and VHS, the equipment necessary for its playback became rarer and rarer.

2 Bay Area Video Coalition, “Playback,” Conservation OnLine, 1996, accessed March 18, 2018, http://cool.conservation-us.org/byorg/bavc/pb96/.

3 Tom Sherman, “The Premature Birth of Video Art,” Experimental TV Center, 2007, accessed March 18, 2018,http://www.experimentaltvcenter.org/sites/default/files/history/pdf/ShermanThePrematureBirthofVideoArt_2561.pdf.

4 The RAND (Research ANd Development) Corporation was founded in 1946 and is an American global policy think tank focusing on the United States Armed Forces. It was notoriously responsible for the nuclear deterrence strategy by mutually assured destruction.

5 Davidson Gigliotti, “A Brief History of RainDance,” Radical Software, 2003, accessed March 18, 2018, http://www.radicalsoftware.org/e/history.html.

6 Beryl Korot and Phylis Gershuny, “Address to Readers,” Radical Software 1, no. 1 (1970): 1.

7 Prior to this, the CV format was manufacturer-dependent, meaning that tapes shot on a Panasonic system could only be played back on a Panasonic system and vice versa.

8 Eric Seigel, “Standards,” Radical Software 1, no. 2 (1970): 8.

9 Interview with Barbara London conducted by the author, December 2017.

10Amy Greenfield, “The Case of the Vanishing Videotape,” American Film 6 (July-August 1981): 17-18.

11 Tony Conrad, “Open Reel Videotape Restoration,” The Independent 10, no. 8 (1987): 2.

12 PAL is the video standard mainly in Europe, while NTSC is the standard in North America.

13 Deirdre Boyle, Video Preservation: Securing the Future of The Past (New York: Media Alliance, 1993).

14 Paul Messier, “Dara Birnbaum’s Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission: A Case Study in the Examination, Documentation and Preservation of a Video-based Installation,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 40, no. 3 (2001): 193-209.

15 This work was done in 2015 by the author of this article.

Main image

Radical Software “Solid State” Volume 2, Issue 4

Autumn 1973, Back Cover

Courtesy of the Raindance Corporation