Repositioning Time and Memory

The Telephone Call by Janet Cardiff

“I thought this whole process of how we’re so in tune with technology now that… we slip into it so well… we’re like cyborgs, in a way, that we can sort of use the camera as an extension of ourselves.”

– Janet Cardiff, in SFMOMA’s Artcast (February 2006)

Since the mid-1980s, Canadian artist Janet Cardiff (born 1957) has created immersive, site-specific multimedia experiences that blur the lines between sight and sound, perception and reality. She has become well known internationally for her engrossing, psychologically riveting works of art using recorded sound and speech. She often collaborates with her partner George Bures Miller (born 1960), and they represented Canada at the 2001 Venice Biennale. Cardiff’s video walk The Telephone Call was commissioned in 2001 as part of The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)’s exhibition and digital tech initiative 010101: Art in Technological Times.

The Telephone Call was the second walk Cardiff created for SFMOMA1 and it is the only time the artist has produced two walks for a single museum.2 Although Cardiff is the author of this work, her long-time collaborator Bures Miller has been involved in the technical and production aspects. Cardiff described SFMOMA’s building as a “temple for a memory map” and a “memory palace”,3 suggesting that museum spaces can be mnemonic devices that evoke our memories through the act of walking. The artist drew from the unique architectural features of the museum building designed by Mario Botta to create a baseline map for the walk.4 “The piece leads visitors through the museum on a meandering tour up the central staircase, taking them briefly into a nearby gallery, and then into a service stairway normally off limits to visitors. The walk concludes with a stroll over the fifth-floor bridge high above the museum’s atrium, closing with a view out to the west hills of San Francisco.”5 Holding a camcorder and wearing stereo headphones, visitors follow Cardiff’s narration as they move through the building, synchronizing their walk with the journey that plays on the camcorder screen.

Janet Cardiff, The Telephone Call, 2001/2023 (video excerpt); purchase through a gift of Pamela and Richard Kramlich and the Accessions Committee Fund, gift of Jean and James E. Douglas Jr., Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein, Patricia and Raoul Kennedy, Phyllis and Stuart G. Moldaw, Lenore Pereira and Rich Niles, and Judy and John Webb; © Janet Cardiff; courtesy SFMOMA

Experiencing one of Janet Cardiff’s audio or video walks is like being transported into a multi-dimensional space that collapses time and three realities – the artist’s world, your world, and the two mixed together.6 By combining pre-recorded video images, music, ambient sounds, her own voice, and our real-time perception of SFMOMA’s spaces, the artist manifests “a net of possible relationships between the inner space of participant and their external environment.” 7

In 2016, The Telephone Call’s spatial component became deeply challenged after the museum’s Snøhetta building expansion, since it relies upon continuous encounters with specific physical elements and structures. The expansion runs contiguously along the back of the existing Mario Botta-designed building, resulting in reconstructions of the central staircase connecting the atrium to other floors and the surrounding spaces attached to it. The central staircase and its nearby galleries play an integral part of the walk. The expansion caused multiple points of irrevocable disruption in the original route, such as the removal of the central staircase between the second, third, and fourth floors, and made the work obsolete to the newly expanded spaces. The overall linear nature of the work’s journey could not be fully manifested without its spatial carrier, meaning the participants couldn’t simply pause, fast-forward, and rejoin the guided video walk to avoid certain missing segments of the entire route.

So, what happens when the relationship between a participatory artwork and the environment in which it occupies is altered or even severed because of changes due to the loss of site? An update to reconnect the sites and reconfigure the route would be essential to preserve the work. The nature of the project required the Curatorial, Conservation, Collections Technical8, and Registration teams at SFMOMA to collaborate closely with Cardiff and Bures Miller to reposition The Telephone Call within today’s time and space and allow for the work’s reactivation. Shifting institutional practices have deeply challenged museum’s typologies, and it has been difficult to define the project in a single term, whether it is a remake, an iteration, a migration, an update, a new production, another edition, or a separate version. It encouraged us to rethink those terms and how they have different meanings and indications for the presentation of the work under different contexts to different audiences. For instance, marking it as another edition may indicate there are multiple editions of the work, and the term remake may separate itself from the original one created in 2001. The complex nature of this project required a holistic approach to time-based media stewardship and a collaborative process where the SFMOMA team wore multiple hats to restage the site, migrate obsolete technologies, and revisit the meaning of accessibility in today’s museum settings.

Similar to the 2001 commission, SFMOMA undertook the role of a producer in restaging and repositioning the work with the artists. They were invited to conduct site visits in 2018 and 2022 where several key physical spaces and objects, such as the emergency staircases, the window next to the second floor’s west side galleries, and Kees van Dongen’s painting La chemise noire (1905-1906) were identified. These are important elements to be made available and accessible not only during the production period for the artists, but throughout the exhibition run for visitors. Several reshoots at SFMOMA were conducted in 2018 and 2023, resulting in supplementary footage that either captured new elements or stood in for missing ones in the museum’s physical environment. The artists diligently measured the loss between remaining and missing elements in physical surroundings, and repositioned both the work that is fixed in the form of a video and the walk that requires audience participation to fully render the experience.

Cardiff plays into the transformation of site to address the passage of time and return to narratives of memory in the 2023 walk. The new dialogue added in the beginning sequence of the work provides participants with context of the artwork’s history and how the artist has restaged the site: “I made this video walk almost 20 years ago. But since then, this building has been completely changed…”, it also elicits feelings of nostalgia for the specific settings the work was created in, “as I look at this footage, I think about traveling back through the decades…It makes me want to hold this tiny world of megapixels more carefully, as if somehow it holds a part of me that I’ve lost.” Certain descriptions of the architectural changes may be read as Cardiff’s sentiments or reflections of the changes of the site, such as “This is the new staircase. One architect erasing another” or “It’s a bit awkward. The new stairs are in a different spot” but they also serve as the artist’s visual markers for reorienting visitors in their environments and an aid to realign the video image on screen with their surroundings.

Apart from the artist’s new narration, most of the soundtrack in the 2023 walk was taken from the original 2001 recordings, including sequences paired with new video footage. The artist employed other visual and audio elements that intercut video footage shot during different production times, like the sounds of a telephone ringing and a camcorder switching on, or video images of television static. These effects acted as the adhesive to fuse remaining and new pieces together, and again draw upon histories in the new narrative, creating more natural transitions between different moments in time. To maintain consistent visual aesthetics, the artists also selected equipment that could help match video resolutions between footage recorded at least two decades apart. Not only are the routes comprised of similar architectural features, but the video lengths between the two are also close to one another. The 2001 walk is 15 min 24 sec and the 2023 walk is 17 min 3 sec long. The latter includes an additional title card, transitioning black screen with narration, and end credits.

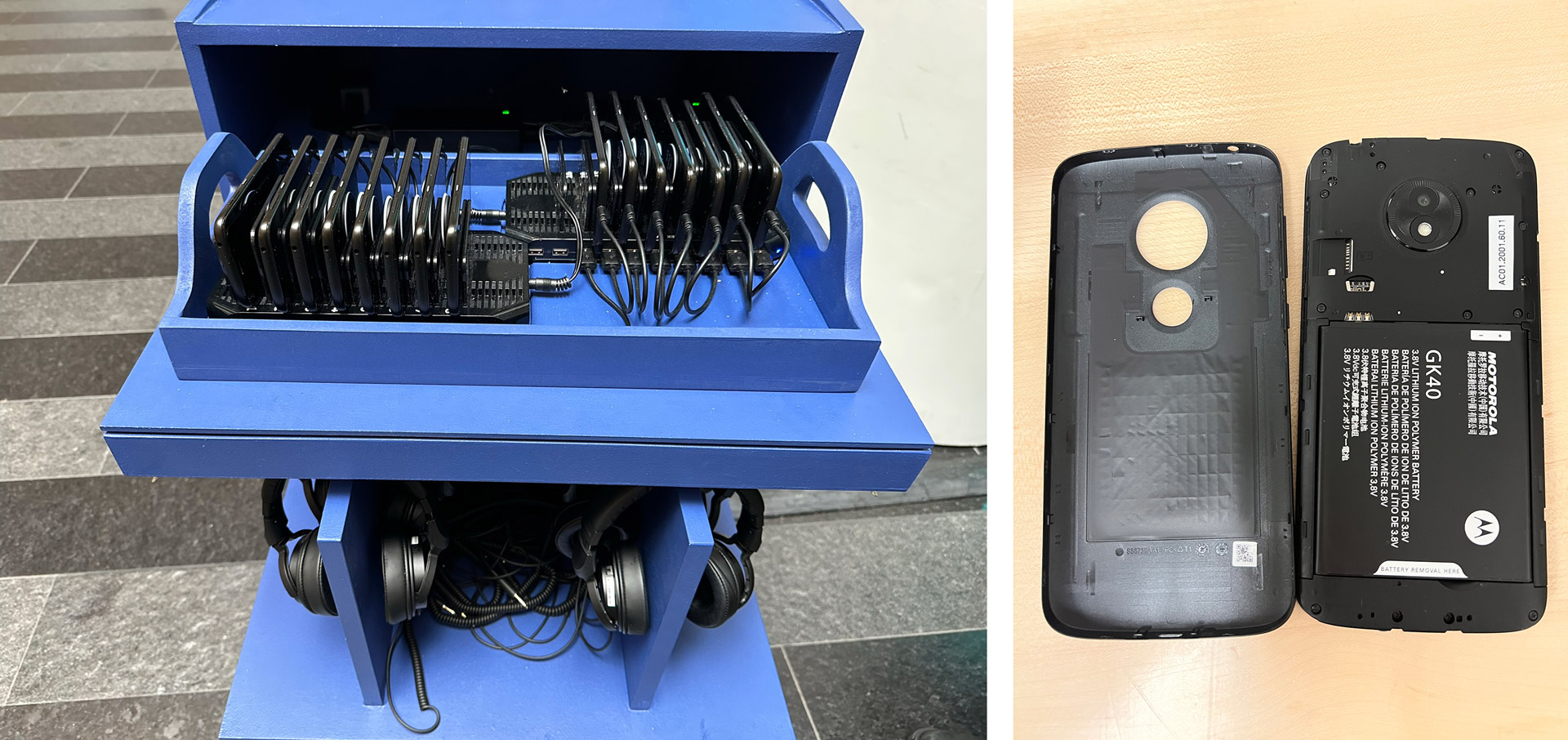

When The Telephone Call was exhibited in 2001, 2008, and 2012, the playback equipment remained identical: a Canon mini-DV camera pre-loaded with a mini-DV tape and a pair of Sony stereo headphones. These small consumer-level video cameras were easily accessible when the work was first displayed. In 2006, the artist expressed an interest in migrating the handheld playback devices while maintaining that the visitor has the feeling of “shooting a video” while experiencing the piece.9 As smartphones and tablets have also become increasingly commonplace, the artist studio proposed a few options based on their experience updating portable devices for their other walks. Even though it is a migration to newer technologies, the current trend towards wider aspect ratio screens limited the device options to discontinued models of mobile phones and portable multi-purpose devices that can better accommodate The Telephone Call’s standard definition video format.

left: Custom-built equipment kiosk for the exhibition Janet Cardiff: The Telephone Call, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, March 25–July 23, 2023; photo: Joshua Churchill

right: Playback device Motorola Moto E5 Play for the exhibition Janet Cardiff: The Telephone Call, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, March 25–July 23; photo: Grace Weiss

Among them, Motorola E5 Play mobile phone was selected for its ideal resolution, and because it ran on the open-source Android mobile operating system that allows more customization compared to other mobile platforms and supported the video playback application MX Player Pro, which was preferred due to its minimal interface that closely mimicked how video appeared on the older mini-DV cameras. Motorola E5 Play mobile phones were discontinued a few years prior to this discussion, so sourcing used phones from the second-hand market presented additional challenges. The Motorola E5 Play phones arrived with pre-installed functions and apps that were unnecessary for the operations of the walk and thus required deletion or disablement upon receipt. Following instructions both from the artists and online articles, a variety of functions within the Android operating system also needed to be restricted or modified to prevent the participants from exiting the media player during the walk. Addressing issues with used mobile devices, the team investigated solutions to unlock the phone from a specific carrier and further strip down the device to be a simple media player.

The 2023 reinstallation also provided the artist and SFMOMA team the opportunity to reconsider and expand the work to be more accessible to a broader audience. Both the 2001 and 2023 walks begin in the first floor Atrium near the entrance to the museum store and conclude in the fifth floor Botta gallery. Staircases are another important narrative and physical elements of The Telephone Call for 2001 and 2023 walk’s routes as participants are guided through three sets of staircases. Key narratives such as Cardiff recalling her father carrying her grandmother up the stairs, and a singer performing Mahalia Jackson’s “Move On Up A Little Higher” take place when participants are in or walking up staircases. During the 2023 presentation, Visitor Experience staff members assisted several wheelchairs users in navigating the walk’s route by using public elevators instead of stairways, and provided access to the video, including sequences happening in stairways, in the atrium lobby and galleries. Also central to the experience of the walk is Cardiff’s narration, and the participants follow her words to navigate both physical spaces and the artist’s fictional world. The participant’s listening experience is psychosomatic and never singular, and the artist believes that sounds come into our unconscious more directly than visual information.10 Our engagement with this boundless soundtrack is imperative to shaping the different realities manifested by the artist and the active participant. Accessibility affordances such as captions and a transcript became a top priority for this work when SFMOMA worked with Prime Access Consulting to assess and improve the artwork’s accessibility for Deaf and Hard of Hearing audiences. This was the first time SFMOMA had produced captions for a time-based media collection work and the artist’s first time generating descriptions of non-speech audio in her walks.

Janet Cardiff, The Telephone Call, 2001/2023; purchase through a gift of Pamela and Richard Kramlich and the Accessions Committee Fund, gift of Jean and James E. Douglas Jr., Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein, Patricia and Raoul Kennedy, Phyllis and Stuart G. Moldaw, Lenore Pereira and Rich Niles, and Judy and John Webb; © Janet Cardiff; photo: Don Ross, courtesy SFMOMA

Transcribing dialogue was a straightforward process; the complexity lies with the descriptions of speaker voices and environmental sounds. The tonality, inflection, and rhythm in the narrator’s (Cardiff’s) recorded voice is distinct and sometimes shifts intentionally.11 The artist wanted to perform a “thinking voice” rather than an “acted voice”, one that in her words, “sound like it’s just going right into your brain.”12 Her words are whispered into our ears and the closed headset brings a critical sense of intimacy into the public realm,13 and establishes a bond between the listener and the narrator. Translating the ways of speaking and the spatial experience of binaural sounds14 for captions and transcript was a challenging exercise. To highlight the stylistic voices of speaking roles in the transcript, the narrator’s dialogue is italicized and descriptors such as “tinny” and “whispered in our ear” were added to emphasize the variations in vocal delivery. For the artist, it was also important to describe the originating position of sounds and how they travel spatially. She included descriptors like “woman in front of you” and “coming from right as if passing them”. As more sounds enter a listener’s experience, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish between pre-recorded ones and those occurring in real time. By introducing captions of diegetic sounds like “narrator’s footsteps begin”, the sound sources are revealed. Where the sounds are coming from may be identifiable but there is still ambiguity around its associations with time.

After SFMOMA’s site transformation, the museum and the artist undertook multi-year production preparations for repositioning and re-activating The Telephone Call. The work’s site-specific and participatory nature not only required adaptations to the changes in the museum’s environments but also careful considerations about balancing between the needs of contemporary audiences and keeping the work as close to the original as possible. Some of these efforts are aligned with the Cardiff’s intent and the ever-changing nature of The Telephone Call’s digital medium, such as the migration of playback technologies and using memory as a narrative mechanism to address site changes. Others revealed inherent challenges due to integral experiential aspects of the work that cannot be fully resolved without radical proposals of other presentation methods. For visitors who cannot participate in the physical act of walking through spaces and up stairways, parts of the walk’s intended experience are lost. Accessibility affordances such as closed captions can only be a beginning measure to render some parts of the walk’s complex and immersive sonic experiences. But this project has provided an opportunity for SFMOMA’s cross-departmental team to develop a better understanding of the physical and conceptual components that shape the work’s multi-dimensional realities.

Cardiff’s consideration of cameras as extensions of ourselves back in 2006 has become even more relevant to today’s audiences with smartphones and tablets being the primary tools for self-recording and witnessing, and social media applications being the most common platforms where users upload and share their recordings. One can imagine that her walks will continue to evolve as the boundaries between virtual, art, and real-life experiences are shifting in a new digital age where more of our connections with surrounding environments and people move into or are simulated in the digital realm. Institutions will also need to adapt to new contexts for the long-term stewardship of Cardiff’s walks as their audiences’ relationships with technology change.

1. The first piece was the audio walk Chiaroscuro I (1997), commissioned for the group exhibition Present Tense: Nine Artists in the Nineties at SFMOMA. It was also the first walk Cardiff has created for the inside of a museum.

2. Cardiff, Janet, and Bures Miller, George. “The Telephone Call.” In Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller. Accessed November 29, 2023. cardiffmiller.com/walks/the-telephone-call/.

3. Dialogue in Janet Cardiff’s Chiaroscuro, 1997.

4. Cardiff, Janet and Weber, John. Internal interview conducted at SFMOMA, July 22, 2000.

5. Cardiff, Janet, and Bures Miller, George. “The Telephone Call.” In Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller. Accessed November 29, 2023. cardiffmiller.com/walks/the-telephone-call/.

6. Cardiff, Janet, and Mirjam Schaub. “Beginning of Walk.” In Janet Cardiff: The Walk Book, 233–35. Köln, Germany: König, 2005.

7. Zyman, Daniela, “at the edge of the event horizon”. In Janet Cardiff: The Walk Book, 11–13. Köln, Germany: König, 2005.

8. Collection Technical is SFMOMA’s team the supports the installation, maintenance, and documentation of time-based media and electronic art works in the museum’s collection and works that have been loaned to SFMOMA for exhibition.

9. Sterret, Jill, et al. Internal meeting transcript, SFMOMA, January 17, 2006.

10. Janet Cardiff, interview by Atom Egoyan, Janet Cardiff by Atom Egoyan, BOMB Magazine, April 1, 2002. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/janet-cardiff/.

11. When the narrator is speaking of something from the past like architectural changes to the museum building, her quality of prerecorded voice becomes tinny.

12. Cardiff, Janet and Weber, John. Internal interview conducted at SFMOMA, July 22, 2000.

13. Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn. “An Intimate Distance Riddled with Gaps: The Arts of Janet Cardiff”. In Janet Cardiff: A Survey Of Works, Including Collaborations With George Bures Miller, 14-35. Long Island City, New York: MoMA P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, 2002.

14. Binaural sound is stereo audio that is recorded through a dual microphone setup, typically spaced and positioned to pick up sound as human ears would. The goal of recording binaural sound is to create a 3D audio effect that simulates sound as if it is being heard live. Binaural sound is best experienced by headphones. The word binaural literally means “having two ears”.

Main image

Janet Cardiff, The Telephone Call, 2001/2023;

purchase through a gift of Pamela and Richard Kramlich and the Accessions Committee Fund,

gift of Jean and James E. Douglas Jr., Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein, Patricia and Raoul Kennedy, Phyllis and Stuart G. Moldaw, Lenore Pereira and Rich Niles, and Judy and John Webb;

© Janet Cardiff; photo: Don Ross, courtesy SFMOMA

Image description

A photo of a light-skinned female figure holding up a smartphone in front of the elevator and one gallery of SFMOMA. The figure, seen from the shoulders up, has long curly hair and wears black headphones attached via auxiliary cord to a smartphone she holds up in front of her with both hands. The space beyond is split into two areas; the right is a bright tomato red elevator bank with oversize text on it; the left is an art gallery with white walls, light oak floors, and track lights on the ceiling. Three abstract paintings hang on the walls and two people move past them in a blur.