PUBLIC DISPLAYS OF AFFECTION

From Public Art to Social Infrastructures

How do we show love in public? To one another—individuals and communities, alike? To our buildings, our neighborhoods, and our cities? And how do components of our built environment and its infrastructures express love back to you?

Not in an abstract sense of eliciting civic pride, but in the material sense—in the cooling breeze of a fountain, in the tasty affordances of a shared meal provided by a well-located picnic table, or in vibrantly patterned pavement that points your attention to a significant building that you might otherwise take for granted. This is civic love—the gestures of organizational care, commitment to shared amenity, and material affection that produces personal attachment to public places and spaces.

While words like love and affection are largely absent from architectural discourse, they appear with striking frequency in public art.1 As a public artist trained in architecture, I’ve long been attuned to this disciplinary split: architecture often maintains a critical distance from emotional language, while public art openly embraces it. Yet despite their distinct conventions, architecture and public art can and should be more closely allied—especially in the service of cultivating civic love. Neither field can singlehandedly eliminate the systemic injustices and violence escalating around the world, but together, they can reshape the built environment as a space for solidarity, participation, and love.

Public art is often framed as a precious object or monument—perched on a plinth, elevated on a pedestal, and detached from the intimate experiences of everyday life. While these works contribute aesthetic and cultural value to our cities and landscapes, their role is often limited to decoration or abstract commemoration. But what if public art could serve as more than a visual accent? How might it become a catalyst for urban design, fostering deeper social engagement?

If infrastructure delivers essential services to a city, “social infrastructure” provides the spatial frameworks that sustain human connection—supporting social interaction, cultural exchange, and civic life. In Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure can help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life, sociologist Eric Klinenberg argues that physical spaces profoundly shape our social fabric.2 Building on this idea, this article expands the notion of “social infrastructures” (in the plural) to describe a range of specific public art formats: platforms, interventions, props, equipment, units, and interfaces. These are not static art installations. These are dynamic architectural frameworks for convening new publics and building community.

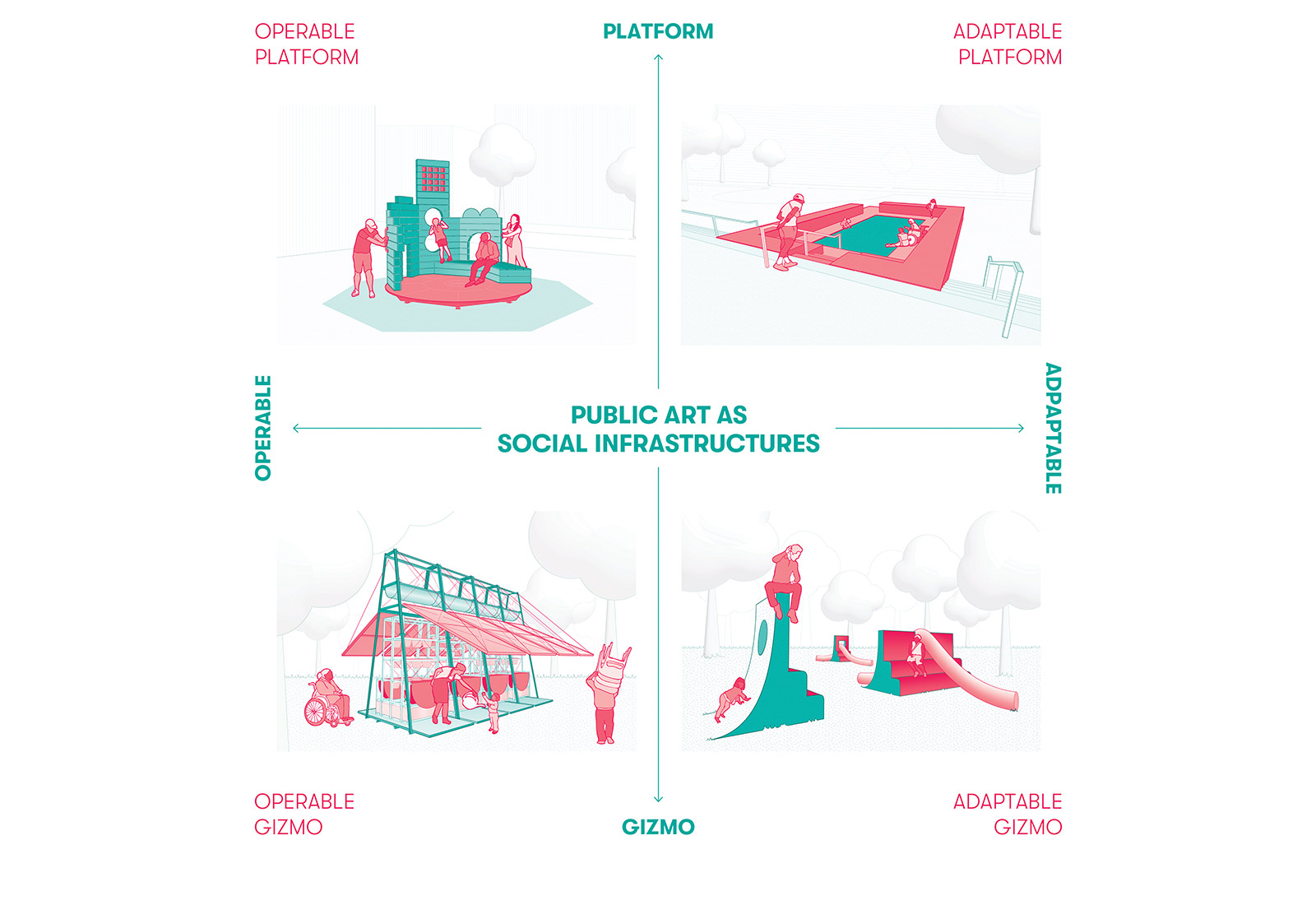

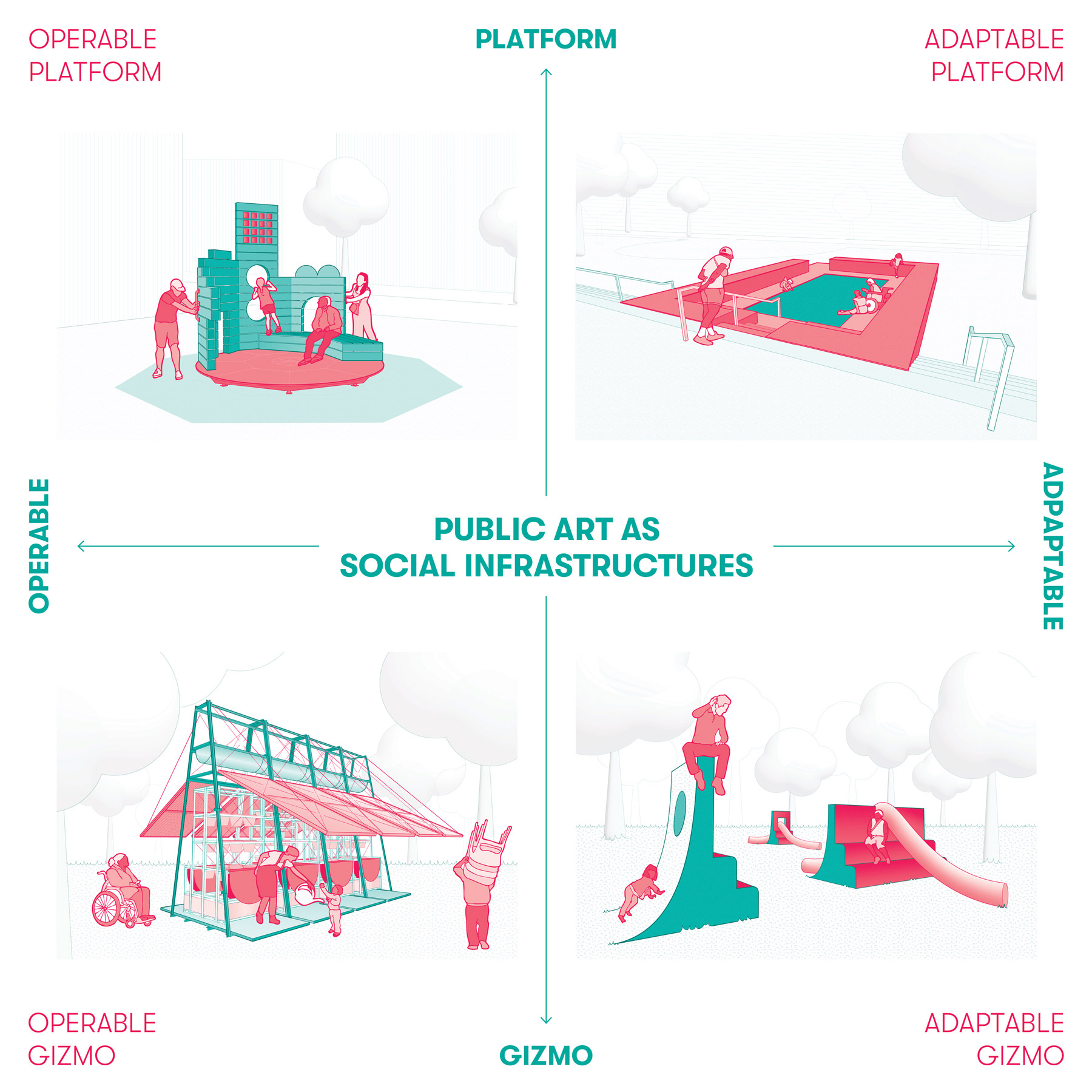

Platforms & Gizmos

A spectrum with platforms on one end and gizmos on the other suggests one range of spatial and programmatic qualities with which social infrastructures operate.

Platforms are frameworks for gathering and collective use. You bring yourself to it, and its users define its purpose. As public artworks, platforms grant permission for community members to inhabit and immerse themselves in some kind of action. Like a stage or proscenium, platforms insert an explicit narrative frame into public space and invite community members to suspend their disbelief about what kind of other worlds are possible within that framework. While they may range in size and scale, platforms generally need to be large enough to support inhabitation of multiple people. Programmatically, platforms support both specific events such as concerts, performances, and political debates and more open-ended and self-directed modes of lingering. While existing public amenities such as stages, bandshells, and plinths offer utilitarian platforms, there is under-delivered potential for public art as a genre to imagine more creative and open-ended platforms. How can the conceptual ingenuity of art practice push platforms as we know them to serve more expansive publics and offer more interactive and open-ended opportunities for communities to express themselves? For instance, what if public artworks offered reconfigurable components that invited communities to establish the orientation, set their own scene, and to define the visual identity of an event?

In contrast, gizmos are instruments for activation and intervention. A gizmo does something to you or with you, often inviting participation through its own behaviors. As public artworks, gizmos operate as artful simple machines. Gizmos often function via specific inputs and outputs that amplify public life. While existing public amenities such as push-button crosswalks, light fixtures, and fire hydrants offer utilitarian examples, there is under-delivered potential in public art as a genre to imagine new or more creative conceptualizations of gizmos. How can the conceptual ingenuity of art practice push gizmos as we know them to initiate surprise and support community building in both functional and spectacular ways?

In a 1965 journal article entitled “The Great Gizmo,” the architecture critic Reyner Banham introduced the word “gizmo” into the art and design lexicon.3 Banham defines gizmo as a device with the ability to transform environmental properties by inserting new forms of performance enhancement. From his vantage point in the 1960s, examples of gizmos included walkie-talkies, surfboards, Polaroid instant film cameras, and camper RVs. For Banham, the gizmo is distinct and independent from the “enormously massive structural deposits” of infrastructure that organize the city and landscape. For example, a camper is a gizmo while a highway is an infrastructure.4 This article borrows the term gizmo, not to suggest that public art become a form of gadgetry, but to imagine how the conceptual model of gizmos as instruments of context reinvention might heighten the social utility and cultural performance of public art. Just as surfboards “make sense of an unorganized situation like a wave,” how can communities steer public art with gizmo-like clarity to drive the reorganization of public spaces?5

While Banham was tantalized by the portability of gizmos and their nimble capacity to be inserted into any site to produce an “instant” transformation, he may have exaggerated the disconnect or independence available between “light” gizmos and “heavy” infrastructure. Any gadget requires a complex supply chain from extraction to manufacturing to delivery and therefore necessarily relies on heavy infrastructure, even if that infrastructure is invisible at the location of the gizmo’s deployment. In the context of public art, social infrastructures acknowledge and embrace the stickiness and exchange among gizmos as (independent) instruments and platforms as (infrastructural) grounds. The spectrum between platforms and gizmos is not a binary dichotomy, but a range with which public artwork may be more or less grounded or entangled in the existing infrastructural systems of the city.

Operable & Adaptable

While platforms and gizmos contrast each other in their differing demonstrations of infrastructural synthesis and independence, both public art typologies share a common middle position along a second, vertical spectrum of social infrastructures that is defined by operable opportunities on one end versus adaptable qualities on the other.

Operable artworks exhibit user-driven activation. Operable artworks typically feature a moving part or kinetic component that is manually powered by users—for example by pushing, spinning, or cranking. In this way, operability centers bodily interaction and human agency. Immediate and event-based, an operable artwork is activated synchronously, in the moment.

Adaptable artworks exhibit a capacity for environmentally or socially responsive configuration. Adaptable artworks are not typically kinetic, but they respond dynamically to external factors, such as time, weather, or program. Their agency resides in the logic of the material or system, not just the user. Gradual and contextual, an adaptable artwork evolves with changing conditions over seasons and time.

These two spectrums of public art qualities—platforms vs. gizmos and operable vs. adaptable—define a bidirectional matrix that describes a field of possibilities for what social infrastructures can look and feel like. Each of the four quadrants is named for the pairing of its characteristics and contains an emblematic case study that exemplifies those qualities. As a diagram, the matrix charts the different ways that social infrastructures offer inhabitation, interaction, flexibility, and agency within public spaces. While all the examples support social use, they differ in scale, mechanism, duration, and the type of participation that they encourage.

OPERABLE PLATFORM: Carousel for Companionship

An operable platform is a surface, setting, or stage that invites manual manipulation or reconfiguration. Cooperative engagement and group effort help bring operable platforms to life.

For example, Could Be Design’s Carousel for Companionship (2023) is a colorful public plaza situated along an underutilized alley in downtown Columbus, Indiana. The project reimagines the alley as a participatory civic room—part plaza, part playground, part stage set—that integrates supergraphic murals on the exterior wall and ground surfaces with a central, carousel-like kinetic platform. Visitors manually rotate and inhabit the carousel, which is designed to sync visually with the surrounding supergraphics and cityscape. The layered graphics and rotating structure invite community members to reconfigure their visual field as they move, subtly transforming the entire space with each interaction.

Could Be Design, Carousel for Companionship

Columbus, Indiana, 2023

Drawing by Riley Vernon and Joseph Altshuler

The shapes and forms that make up the geometry of the supergraphics and carousel backdrop are sampled and abstracted from the city’s iconic architecture. As visitors spin the carousel, it periodically aligns with and echoes perspectival views of nearby buildings (such the tower of Eliel Saarinen’s First Christian Church)—kind of like a visual “rhyme.” The carousel’s shapely apertures also become operable viewing devices that periodically align with the painted wall graphics. Carousel for Companionship thrives on part-to-part engagements: each motion, shift in perspective, or communal action activates the visual and spatial dialogue, revealing new alignments and patterns. Operability, in this case, is both a visual and physical choreography between user and space, offering a kinetic, interactive opportunity to express civic love and commemorate the city’s modernist architectural heritage.6

Unlike a conventional merry-go-round in a playground, the carousel’s rotation is calibrated to be intentionally difficult for an individual to spin on their own, so as to encourage cooperation with others. If multiple individuals work together simultaneously, they can propel faster speeds of rotation or enact more precise alignments with their surroundings for visual and functional effects. For example, community members can rotate the carousel to face inward for more intimate events like poetry readings or outward toward the street or alley for concerts or larger events. Whether it’s a platform for one-person performances, high school bands, or informal play, Carousel for Companionship becomes a stage for civic life, fostering moments of connection that are both intentional and spontaneous. As an operable platform, cooperative physical effort yields the maximum opportunity for reconfiguration and community agency.

Zack Morrison of Could Be Design reflects:

“While Carousel for Companionship was originally commissioned as a temporary installation for a public art biennial, the public space that the installation brought to life is now a permanent plaza in the heart of the city’s downtown district. Carousel offered the city an invitation to take architecture for a spin. In addition to launching the Carousel (as an art object) into motion, the project also demonstrated how to animate an underutilized lot, providing a participatory prototype for how a permanent outdoor cultural venue could operate there. Carousel was recently relocated to the interior of a former shopping mall in Columbus that is being converted into a public parks department facility. In its new home, Carousel continues to model how operable platforms build audiences by inviting the participatory reconfiguration of public space.

Carousel also points to future directions in our public art practice. Part sculpture, part community porch, and part optical toy, we’re currently working on new operable platforms that invite community members to reimagine public art as a kinetic architectural framework—one that fosters neighborly interaction, reshapes the commons, and commemorates untold stories.”7

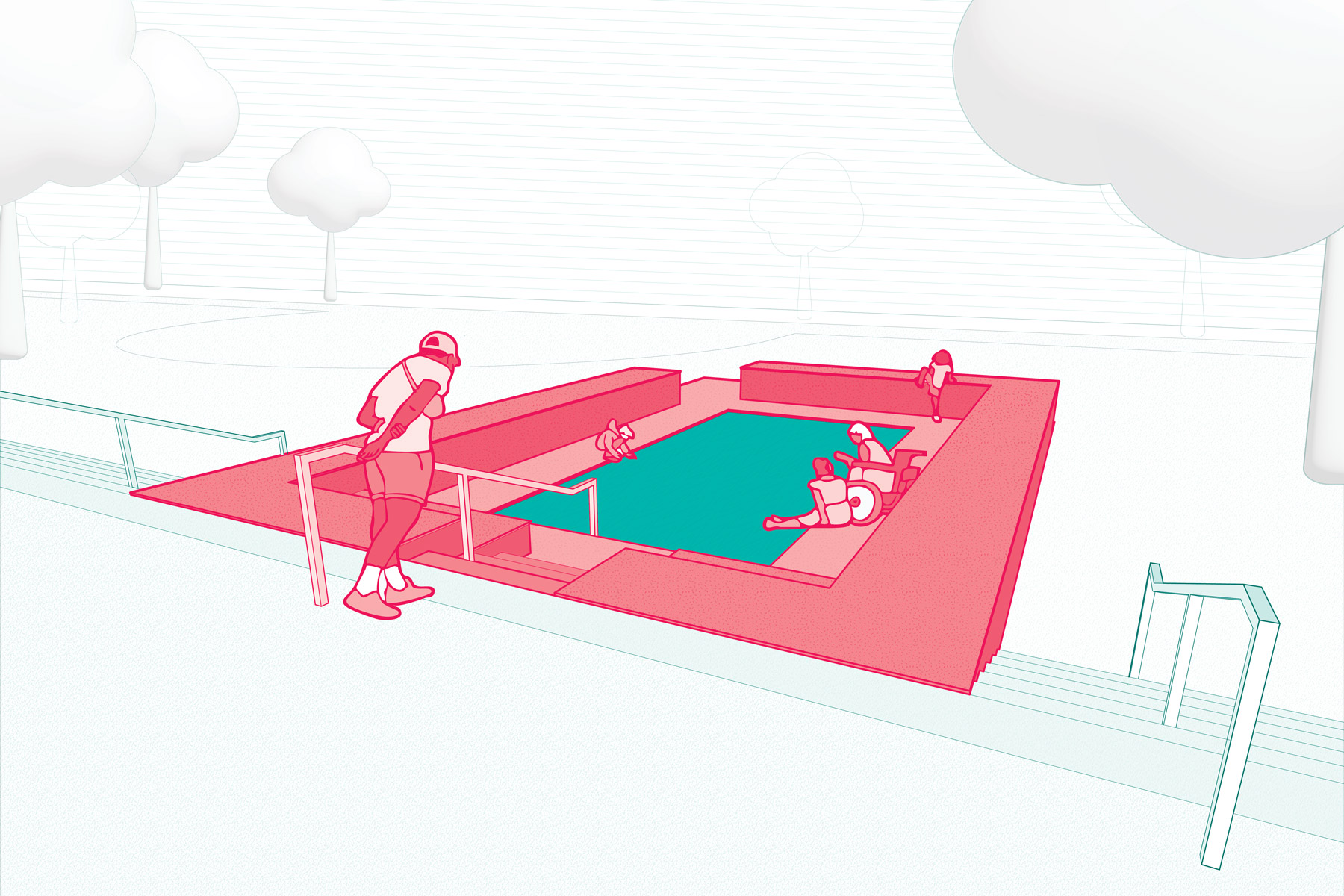

ADAPTABLE PLATFORM: Pool/Side

An adaptable platform is a surface, setting, or stage that changes over time based on social, cultural, or environmental conditions.

For example, Akima Brackeen’s Pool/Side (2025) is a public wading and reflection pool installed on the plaza in front of the public library in Columbus, Indiana. The project is defined by its perimeter seating platform that invites community members to sit and linger around the pool, even if they choose not to get their feet wet. The seating platform integrates sectionally into the monumental steps of the library’s front plaza such that one end of the platform is coplanar with the raised section of the plaza, located at the top of the steps and in front of the library’s main entrance. The project invites multiple entry thresholds and gradations of access from various sides: a wheel-chair accessible ramp offers a seamless threshold from the south, a table-height bleacher condition challenges more adventurous visitors to climb onto the elevated seating along the east and west, and steps along the north offer a more direct and gradual descending approach into the waters.

The changing physical properties of water that occur over different weather patterns and seasons amplify the platform’s adaptable potential. On hot summer days, Pool/Side offers an active and refreshing oasis to splash and submerge your feet. On cool autumn days, visitors are less likely to enter its waters, resulting in a calm reflection pool and a tranquil space for community members to sit and reflect. Upon winter’s first freeze, the pool transforms into a small but sparkling ice rink, daring adventurous folks to slip and slide along its glazed surface.

As an adaptable platform, this public artwork challenges the typically contained, managed, and/or monetized attitudes that regulate communities’ access to pools of water. It also challenges the expectation that inhabiting water should be an act strictly reserved for purposes of recreation and fitness. What if shallow pools and aquatic environments were more regularly integrated into the everyday surfaces of the city’s hardscapes? What if public access to water was less of a special, controlled event—like the specificity of seeking out and committing to an afternoon at the swimming pool—and more of an everyday, routine encounter? Ultimately, Pool/Side demonstrates a broad infrastructural ambition for public artwork. It suggests that public art might be less of a discrete object and more of a series of integrated sensorial environments that comprise the basic physical and organizational structures of the city.

After the Pool/Side opened to the public in August 2025, Brackeen reflects, “Embedded in a relatively blank existing public plaza, Pool/Side invites interaction at multiple scales, from playful splashing to quiet contemplation. Since its installation, Pool/Side has shown how intervention can transform our reading of familiar forms in the public realm: a shallow reflecting pool that might traditionally signal stillness instead became a vibrant stage for imagination, spontaneity, and collective care. No matter what time of day, people can’t help but gather there. Kids comically swim laps in its 8-inch depth, while parents and companions sit, soak their feet, and chat.”8

ADAPTABLE GIZMO: Noodle Soup

An adaptable gizmo is an instrument or machine that changes over time based on social, cultural, or environmental input.

For example, Office Ca’s Noodle Soup (2018) is an interactive kit-of-parts that collectively produces a constructed landscape on the grounds of the Ragdale Foundation in Lake Forest, Illinois. The kit-of-parts includes fixed, stepped structures that function like bleachers, and soft, linear, pliable furnishings—the “noodles” that give the project its namesake. Visitors are invited to reposition the noodles and to slot them through the apertures, cut-outs, and notches that punch through the bleachers. When the noodles engage into or onto the bleachers, they optimize their collective utility as a device for seating, snuggling, or climbing.

Noodle Soup is a strategy of multiples. Unlike most public artworks that present a singular, precious object, Noodle Soup includes over a dozen discrete parts that are distributed over the landscape with minimal compositional hierarchy. While each fixed bleacher structure is similar and constructed with a consistent set of materials and shape language, none are identical. Some are tall and skinny. Others are short and wide. Some have square apertures, some have circular windows, and still others have open slots. They appear as a cohesive system, but their variable dimensions offer a range of unique engagement opportunities for different body types and performances.

Office Ca describes the project as an “architectural scale interface.” An interface is defined as “the place at which independent and often unrelated systems meet and act on or communicate with each other.”9 Noodle Soup operates as an interface between humans and architecture (the social and programmatic effects of people interacting with the noodles) and between architecture and architecture (the physical affordances created by noodles interacting with the bleachers). As an adaptable gizmo, the configuration and utility of the bleacher-noodle pairings necessarily evolves, reinventing the context of the Ragdale Foundation’s festival lawn after each performance.

Looking back at project’s impact seven years later, Stephanie Sang Delgado of Office Ca shares,

“Noodle Soup was designed around a simple premise: how do we design an architectural-scale interface? By focusing on two systems, the static walls and movable noodles, visitors were asked to engage directly with the project by changing their landscape with the noodles, thereby providing a playscape for everyone. Noodle Soup was the beginning of our practice’s trajectory in designing architecture and environments as interfaces.

Building on this project, we have now begun a line of inquiry into analog computation, a way of exploring technological logics through physical material and tectonic applications. Analog computation has a rich history that includes tabulating abacuses, punch card weaving looms, and even electronic circuit simulations. As the world becomes increasingly reliant on black-boxed, seemingly immaterial modes of digital computation, we feel that analog computation can be a tool to reflect on the materiality of computation. Our interest in analog computing is being explored through one main provocation: what if a billboard were an interactive piece of social infrastructure? Here we are asking the public to look beyond the image. It can be equated to looking at a digital screen for its pixels rather than the image those pixels produce.”10

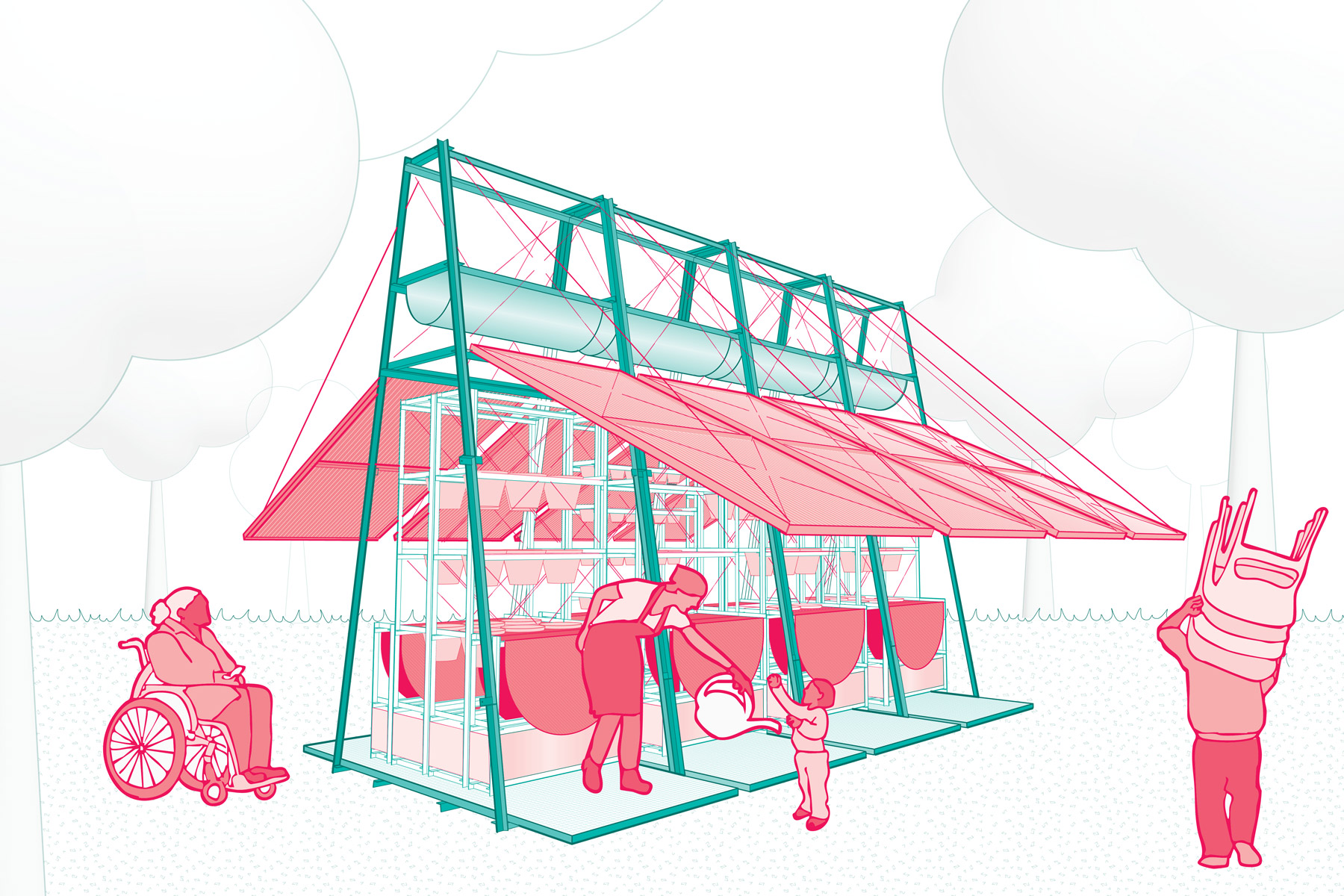

OPERABLE GIZMO: Your Greenhouse Is Your Kitchen Is Your Living Room

An operable gizmo is an instrument or machine that invites manual manipulation or reconfiguration. Like a Swiss army knife, operable gizmos often transform from one state to another to offer different types of utility and performance attuned for different social situations or cultural happenings.

One-part urban farm and one-part picnic table, Office for Roundtable + JXY Studio’s Your Greenhouse Is Your Kitchen Is Your Living Room (2024) is a social infrastructure in Guangzhou, China. This public artwork demonstrates how the functional qualities of furniture, typically confined within domestic interiors, can activate outdoor public spaces and translate the sense of interiority into the city.

Office for Roundtable + JXY Studio,

Your Greenhouse Is Your Kitchen Is Your Living Room

Guangzhou, China, 2024

Drawing by Riley Vernon and Joseph Altshuler

This modular pavilion, constructed with angle steel and encased in polycarbonate sheets, offers multiple operable parts that are organized in nested layers. Starting from the exterior, the pavilion is clad in a series of operable panels that can be tilted opened and closed, alternately facilitating a quasi-interior microclimate that extends the outdoor growing season for produce (like a cold frame) or an open-air porch-like structure that invites communities to share in its bounty. The pavilion houses a series of growing racks, kitchen counters, and folding tables, all perched on casters so that they can be wheeled out from the pavilion’s casing, transforming the artwork’ surroundings into a pop-up dining room or plant nursery.

Your Greenhouse Is Your Kitchen Is Your Living Room is operable on multiple levels. Adjustable cables stabilize the pivoting greenhouse panels at variable heights. The semicircular table panels pop-up when needed for events or neatly collapse for dormant storage. Rainwater, harvested and filtered through the metal reservoir overhead, circulates through the pavilion to support horticultural or culinary requirements.11 On one hand, the kinetic operable parts facilitate a compact yet versatile object—a set of functional, infrastructural affordances. On the other hand, the operable parts also broadcast the artistic promise of responsive versatility. As a kinetic sculpture, the moving parts operate theatrically to produce a public performance of its own, independent from its functional accomplishments as a clever gizmo.

Reflecting on the project’s community impact, Leyuan Li of Office for Roundtable shares:

“Our practice focuses on creating forms, spaces, and events of togetherness, exploring diverse types and scales of architectural interiors as instruments to build communities and cities. This pursuit emerges from a reimagination of interior parts—like domestic furniture and water fixtures—materialized through scalable, portable, and adaptable installations that actively engage the body, nature, and society. Building upon Your Greenhouse Is Your Kitchen Is Your Living Room—where food was positioned as a transformative medium supporting community through urban agriculture—we are now increasingly interested in the agency of the dining table as a site of social and artistic production. Guided by a prescribed set of dining etiquette and rules of play, the table becomes a stage for spatial and social alternatives to established policies and protocols, cultivating a social infrastructure of care in response to broader collective crises.”12

Affectionate Futures

Whether cooperating with a companion to spin a carousel, getting your feet wet in a reflecting pool, snuggling with a noodle in a public space, or unfolding a table for an impromptu picnic, architectural strategies offer an expanded opportunity to elevate and animate the role that public art plays in our communities. Public art as social infrastructure grants permission for us and our fellow community members to share and amplify the affection available among built environments.

The social infrastructures matrix presented here is a starting point for imagining organizational and operative frameworks for inhabitable public artwork, but it is not exhaustive. Like the popular notion of “love languages” for human relationships, affectionate demonstrations of civic love similarly operate via multiple modes.13 What civic love languages does your work speak?

Acknowledgement: Some ideas in this article were developed in thought partnership with Akima Brackeen. Altshuler and Brackeen are co-curators of a multi-city exhibition entitled Public Displays of Affection: Social Infrastructures and the City which will open at the Krannert Art Museum in 2027 and the Chicago Architecture Center in 2028.

1. The commercial success of Robert Indiana’s pop art LOVE sculptures, with over six dozen iterations installed all over the world, is emblematic of public art’s comfort and ease with broadcasting the idea and representation of “love.” Contemporary riffing on Indiana’s seminal work, such as the public art practices of Laura Kimpton and Roberto Behar & Rosario Marquardt, demonstrate LOVE’s ongoing relevance and legacy.

2. Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure can help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life (Crown, 2018).

3. Reyner Banham, “The Great Gizmo” in A Critic Writes: Essays by Reyner Banham (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 109–118.

4. Ibid, 113.

5. Ibid, 110.

6. See Joseph Altshuler and Nekita Thomas, Supergraphic Landscapes: From Public Art to Urban Design (Applied Research and Design Publishing, 2026).

7. Zack Morrison, email message to author, September 15, 2025.

8. Akima Brackeen, email message to author, September 18, 2025.

9. Merriam–Webster Dictionary, s.v. “interface (noun),” accessed June 15, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/interface.

10. Stephanie Sang Delgado, email message to author, September 16, 2025.

11. Office for Roundtable.

12. Leyuan Li, email message to author, September 18, 2025.

13. Gary Chapman, The Five Love Languages: How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate (Northfield, 1992).

Main image

Public Art as Social Infrastructures matrix

Diagram by Joseph Altshuler

Drawings by Riley Vernon and Joseph Altshuler

Image description

A diagram consisting of pink and blue text and illustrations, with the words “PUBLIC ART AS SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURES” written at the center with four arrows pointing outward from it, which point to “PLATFORM” at the top, “ADAPTABLE” on the right, “GIZMO” at the bottom, and “OPERABLE” on the left. In each quadrant that these arrows form, is a digital drawing and more accompanying text. In the top left corner are the words “OPERABLE PLATFORM,” accompanied by a drawing which shows four people interacting with a spinning structure. The drawing in the top right quadrant displays a pool with various entrances and four people standing or sitting around it, alongside the words “ADAPTABLE PLATFORM.” In the bottom right corner is a drawing of an outdoor scene of people interacting with various structures with slopes, tubes, and steps, with the words “ADAPTABLE GIZMO” in the bottom right corner. Lastly, in the bottom left corner are the words “OPERABLE GIZMO” and a drawing that shows four people around a covered, paneled structure.