Pretty Cool

Carl Thoma on Collecting Digital Art

Carl and Marilynn Thoma are art collectors and philanthropists. Under the umbrella of the Thoma Art Foundation they lend and exhibit works from their collection, support innovative individuals and fund pivotal initiatives.

In 2014 they set up two exhibition spaces, Art House in Santa Fe and Orange Door in Chicago, where they display the four distinct areas of their collection: Spanish Colonial, Japanese Bamboo, Post-War Painting and Sculpture (notably color field and hard-edge abstraction), and Digital and Electronic Art, which is the focus of this article. They began collecting in 1975 but only took an active interest in digital art about a decade ago. In 2015 they initiated a unique annual award for significant contribution to writing about Digital Art. In February 2018, Carl Thoma spoke with VoCA’s Kate Lewis at his offices in Chicago about his collecting and passion for digital art.

Kate Lewis: What is it that motivates you to collect?

Carl Thoma: I’d like to give a little bit of background because this applies to a lot of art collectors in the world right now. So much wealth today is being created by financial transactions as opposed to building railroads or steel mills, so you’ve got this massive amount of wealth worldwide that at the end of the day is just cash. I think this is probably what’s driven contemporary art prices so high: everybody wants to feel like they own something tangible. You could buy a fifty million dollar penthouse in New York or you could buy a ranch somewhere, or a ski resort, but a lot of us have also evolved to looking at art as a way of creating something tangible in our lives. Many of us start out buying art just to decorate our homes, but then we evolve.

I started out as a venture capitalist, and we’re always looking for new areas to invest. I think that’s what caused my wife and I to collect across a much broader spectrum than the average person.

Lewis: How did your collecting evolve?

Thoma: I’m a very neat and orderly person and I like hard-edged art. I also happen to really enjoy color, so I guess that’s kind of my personality. We got a copy of The Responsive Eye1 catalog from an exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in 1965 and then we set out on a mission, my daughter and I, to see how many of these artists in the show we could collect. I think we probably have at least fifty artists from it. The exhibition was a bellwether standard around optical art, and my obsession for that evolved into an interest in digital art.

Lewis: What artwork in particular provoked this interest?

Thoma: I would say the hard-edge color field paintings led me towards art that uses light and space, such as Dan Flavin or Robert Irwin’s newer works, and from there we were introduced to a piece by Leo Villareal; I was fascinated by the colors! To me, systemic art can be very much akin to hard-edge art and a computer algorithm itself is very hard-edge; it’s hard written code, but when code performs different functions it can generate a huge range of color combinations and emblems and symbols. So that’s how it got started, buying a Leo piece. Then what happens is you get to know the dealers who sell you these pieces and they just keep introducing you to more artists. If you leave video out of it for a moment, there’s not a lot of dealers, it’s probably less than ten that we work with. Ten years on we now have four significant pieces by Leo.

Lewis: How did you go about building relationships with these artists and dealers? Do you visit studios?

Thoma: I would say either by visiting the artists’ studios or knowing their dealers super well, seeing them in a show, and following what they are working on next. You want to understand their next evolution, see what they’re doing and try to buy those. It’s exciting to monitor new work as it’s progressing.

Lewis: I read that you’re interested in “vintage digital,” can you explain what you mean by that?

Thoma: You might jump in somewhere [in the digital media timeline], maybe in the middle, but then after you land you want to go back and unearth more of the history. Ultimately if you think about a museum getting the collection eventually you need to bring some depth to allow them to tell a little bit of the story. That’s partly what led to acquiring some of the early computer drawings back when a computer could only output to a plotter, including artists like Vera Molnár (b.1924) and Harold Cohen (1928-2016) who at this time don’t even have gallery representation. You have to go and meet these artists because they won’t sell to a collector over the phone, and that can be a lot of fun. Jason Foumberg, Curator at the Thoma Foundation, and I spent a lot of time arguing about what’s significant and what’s not.

Lewis: Did you have the opportunity to meet Harold Cohen?

Thoma: Yes. He said he wouldn’t sell us anything unless we came out to see him, so we went out to San Diego and met with him. He was a very interesting person. One particular work we acquired when visiting Harold’s studio is twenty-two feet by ten feet. It’s rolled up, I don’t know if we could ever show it or not. The good news is the Tate’s got one just like it. He created an algorithm that would instruct a little robot to go around and draw on a canvas. He colored the images himself, then he figured out how the robots could do their own coloring. We acquired one where the machine actually did the all the coloring. Later on he concluded that the process for introducing color into the drawings was pretty secondary so why not have a machine do it for you. His feeling was the art was all in the lines being created and then in the computer; initially Cohen selected the colors but later the computer algorithms selected the colors. So at the end it was totally machine-made art.

Harold Cohen, RA46, 1978

Computer-generated drawing, enlarged and hand-colored in acrylic on unstretched canvas

© Harold Cohen Trust, Courtesy of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation

Photo by Thomas Machnik

We went through probably two or three hundred of these drawings and we picked out the ones we wanted for the collection. We considered factors such as the condition of the paper, the folds in it, and various color combinations we happened to like. We didn’t want everything looking the same.

Lewis: In Real Time is the current exhibition at your Art House gallery in Santa Fe. Could you talk a little about the work by Eduardo Kac, which is based on the pre-internet system, Minitel, that became available in France and Brazil in the 1980s?

Thoma: He’s a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and everybody, including the artist Lynn Hershman Leeson, seems to like the work. Most of us don’t realize that at that time that piece of hardware in France was more relevant than Microsoft or Apple. Neither one of them had even started by then. I think of it as a novelty piece. We first saw it when we visited the exhibition Electronic Superhighway 2016–1966 at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, and we’ve since gotten to know Eduardo because he’s based here in Chicago. He’s a very smart person and likes to do really cutting-edge art: he has manipulated DNA to make art! How do you create art doing that? He’s kind of an artist’s artist.

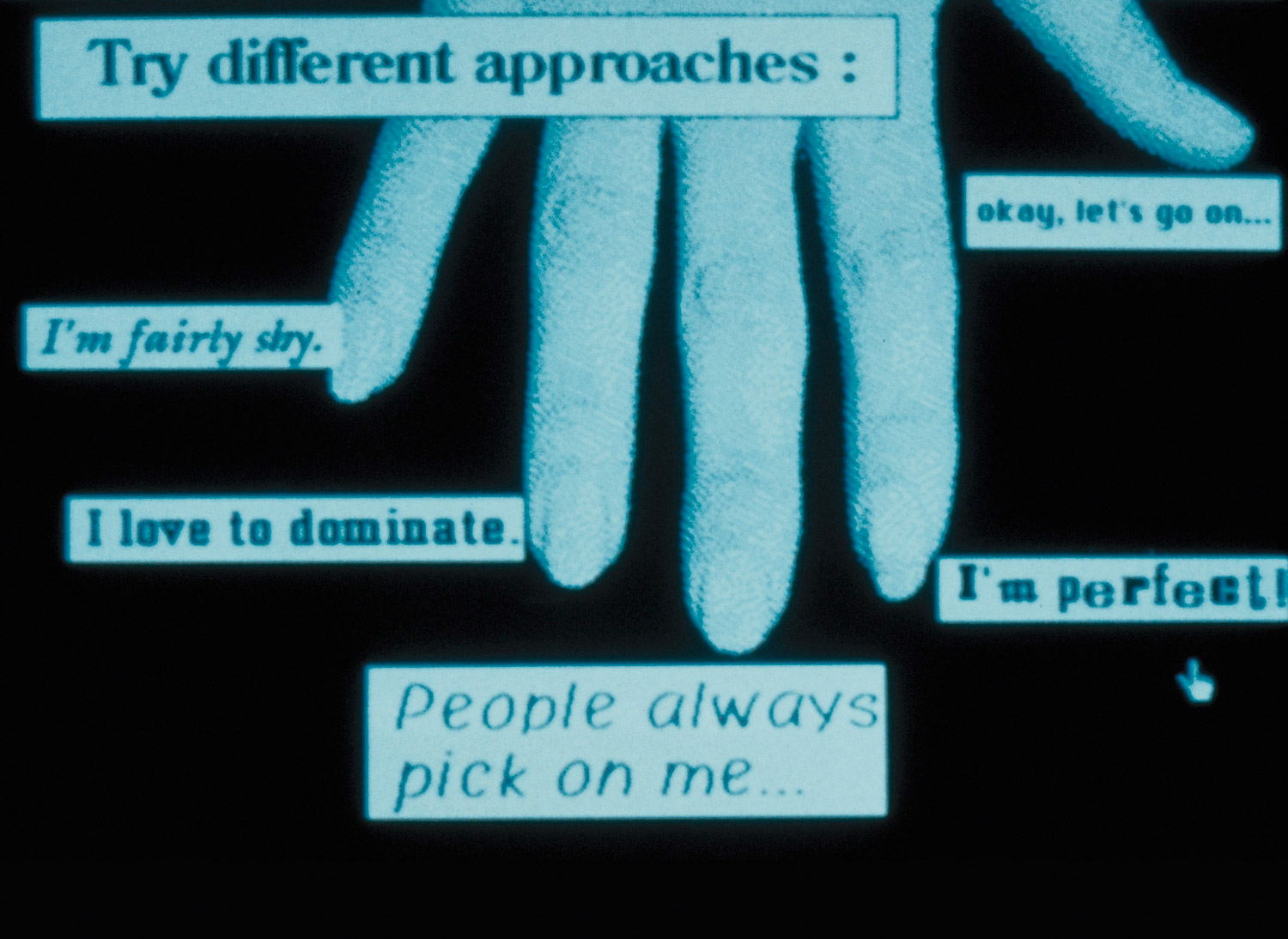

Lewis: You mentioned Lynn Hershman Leeson. You have that fabulous piece in your collection, Deep Contact (1984-1989).

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Deep Contact, 1984-1989

Interactive touchscreen installation, Dimensions variable

Thoma: Lynn’s in her mid-seventies and she’s probably received more publicity in the last two or three years than she did the previous thirty. I got to know her when the Kramlichs2 had a get-together out at their new place a year or two ago and she was there. The piece we have by Lynn runs as if on a slow computer, just as it was in the 80’s, and the feedback loop is too slow for most people’s attention span; most people don’t realize how slow early computers were. I remember when I first got into computers, you dropped your cards off at ten o’clock at night and you’d get the output the next morning at six. If there was an error in the lines of one of your codes this meant that you got nothing that morning, and had to correct and resubmit it by ten again. So then the speed was running at a twenty-four hour turnaround.

Lewis: Since 2014 you have established two public exhibition spaces, but do you live with any of your digital works at home?

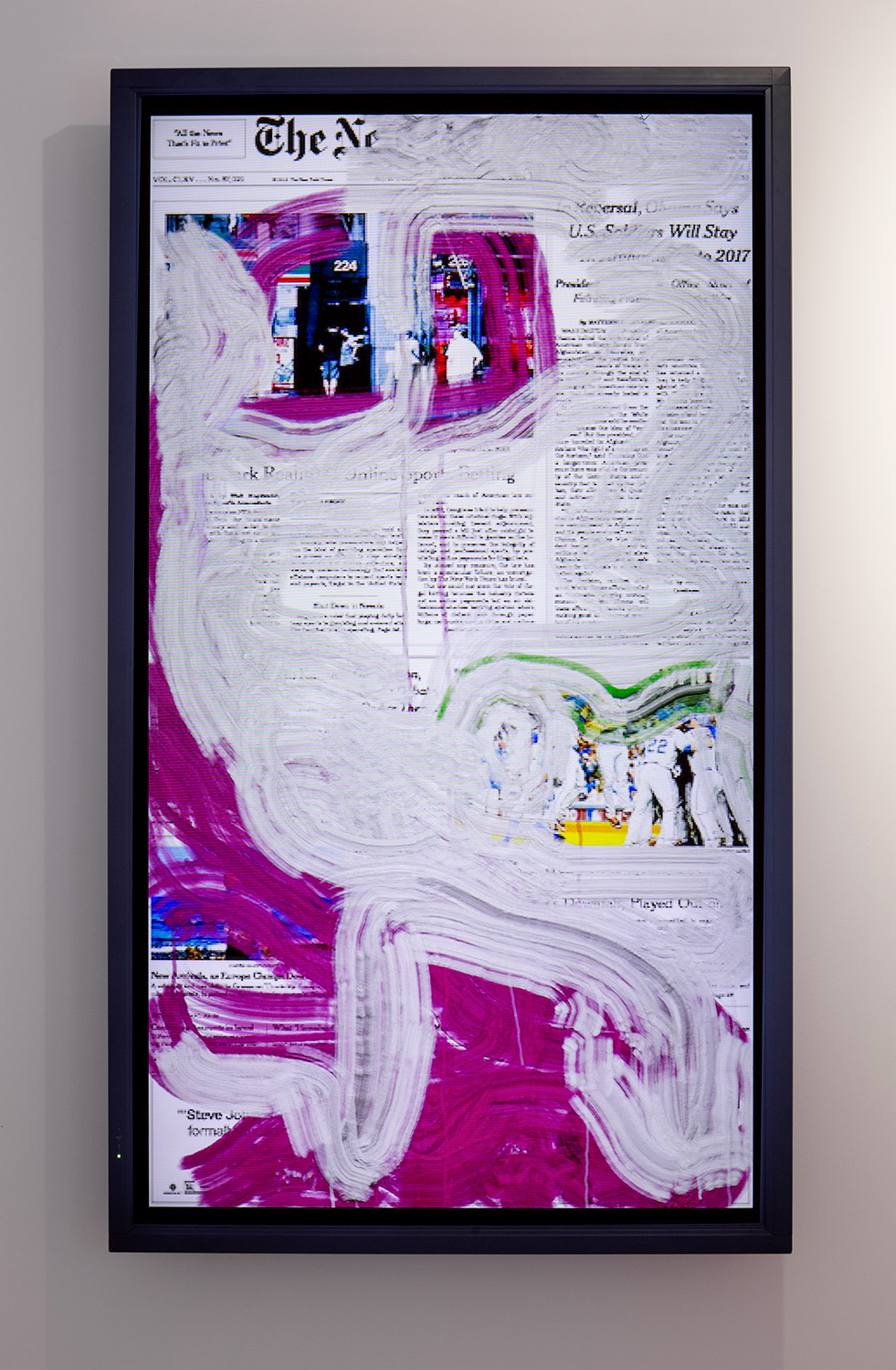

Thoma: In the past we have lived with Jason Salavon works, and at the moment we have a work by Siebren Versteeg called Daily Times (2012). It is probably my favorite piece because every morning it loads the New York Times so you can walk in and see what the headlines are for the day. Then by the end of the day, you can’t even recognize the New York Times and every day is a different algorithmic painting. It’s been running seamlessly for two or three years. I think most of this digital art just needs more space than the average home can provide. But for some of the newer works we’re looking at, even Orange Door, which is probably three thousand square feet, isn’t big enough. Some of these works require a kind of black box environment. I don’t know, that’s a concern at the moment.

Lewis: To what extent are you involved with the exhibitions at Orange Door and Art House?

Thoma: I’d say we leave that up to Jason and then we all kind of weigh in on whether we think things look good together aesthetically or whether there’s enough excitement through the six rooms. Jason does a nice job of coming up with themes that I wouldn’t have ever thought about.

Lewis: How soon after collecting a digital work do you install it? I was wondering if you sometimes acquire something you can’t install at home, are you really motivated to get it up and running in one of your galleries?

Thoma: Yes, I’d say we like to install a piece within the first twelve months. And part of the reason we do that—and you must be able to relate to this in your day job as a conservator at MoMA—is that when you buy this type of art you’ve got to get it out of the box and get it working. We have a collection storage space in Santa Fe, and our practice has evolved so that within the first six weeks of acquiring a digital work, we install it and test it. Some of the artists say you need to run it every so often, almost like a car. This art doesn’t get better not being used.

Lewis: In 2015 the Thoma Foundation began giving grants for writing on digital art. What inspired you to create these annual awards?

Thoma: That happened after Mira Burack, former Associate Director of the Thoma Foundation, spent several months talking to everybody in the field and the consensus was to promote more dialogue about digital art. We’re pleased with it and are currently going into iteration two of trying to figure out how we can further advance the writing field beyond the award. One of our criteria is to fund the publication of books and catalogs for exhibitions of digital art with the aim that future scholars will be able to go back and experience these exhibitions through their publications and read about what was going on at the time. We see it as a part of a larger effort to capture as much of what is going on here and now as possible so that a hundred years from now there will be information out there for people to access, in addition to searching the archives on the internet.3

Lewis: From your vantage point as a collector, would you say there is a community of private collectors out there?

Thoma: There could be. It’s pretty loose right now. From our perspective, considering the kind of art we collect, Ahmet Kocabıyık from Borusan is probably the leading collector in the world. And then the Kramlichs are more into video, so their collection doesn’t overlap that much with what we do. There are no cocktail parties in Miami for collectors like us to get together. I think it’s a pretty small community.

I feel we would benefit from creating a more collaborative effort, because the thing that’s different about digital art, compared to oil or acrylic on canvas, is the artist is making a minimum of probably three and maybe a maximum of six in an edition. Some of them spin all the way out to twelve, so then there’s maybe enough to go around. We could all help ourselves by trying to collaborate more on the conservation of this kind of art and working with the artists. The Whitney started up a little digital group, led by Christiane Paul, Adjunct Curator of New Media Arts at the Whitney Museum of American Art, so it’s a nice chance to meet with people and talk about things.

Lewis: What is the next exhibition you are working on?

Thoma: We are presenting an iteration of the Transfer Download4 in Art House, Santa Fe opening in June of 2018. It’s a survey of new digital animation curated by Kelani Nichole. Visitors will be able to select from a menu of twelve artworks to experience in a viewing room that mimics virtual reality. The roster is an international selection of some of the best artists working in this medium right now.

1 “The Responsive Eye” February 23-April 25, 1965 at The Museum of Modern Art

2 Pamela and Richard Kramlich have collected video art since the late 1980s amassing one of the world’s largest collections. In 1997 they established the New Art Trust, which supported the project Matters in Media Art: Guidelines for the Care of Media Artwork.

3 https://thomafoundation.org/category/grants-and-awards/

4 http://transfergallery.com/category/exhibitions/

Further Reading

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2914

http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/electronicsuperhighway/

Main image

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Deep Contact, 1984-89

Interactive touchscreen installation

© Lynn Hershman Leeson

Courtesy of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation