One-size-never-fits-all

Maintenance Culture and Media Preservation

Elena Cordova is the project director for Maintenance Culture, and is trained as an archivist and preservation specialist with degrees in design history and material culture as well as information science. Eddy Colloton is a media art conservator with a graduate degree from the NYU Moving Image Archiving and Preservation (MIAP) program. The two, who met in 2022 when Eddy collaborated with the tools and resources team at Maintenance Culture, connected via Zoom on April 28, 2023 to discuss the current state of contemporary art preservation, and unpack some of the myths and challenges in the field of time-based media stewardship.

Eddy Colloton: OK, so let’s start broad: what is Maintenance Culture?

Elena Cordova: Maintenance Culture is the brainchild of Myriad Consulting, a preservation nonprofit, and its executive director Frances Harrell. The project is funded by a grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities Preservation and Access Department, and is designed to support collecting institutions as they solve preservation challenges related to time-based media, born-digital works—really any sort of creative digital content that is coming into not only arts-focused institutions but cultural heritage organizations of all types.

Maintenance Culture is particularly focused on developing tools and resources and training programs to help folks who work in small and mid-size museums, libraries, and archives—as well as other community-based collecting institutions like historical societies and even galleries. It’s an ongoing initiative, aimed at developing a curriculum of workshops that get people in the room talking about the problems they’re having—while also trying to find some solutions to those problems together and in-person. Out of these workshops we are also drafting a field guide of sorts—a more lasting resource that will present a digital preservation workflow for time-based media and or other born-digital creative works.

Another priority for Maintenance Culture is to facilitate conversations between curators, registrars, archivists, and other people working at cultural heritage organizations and the artists who are creating born-digital work. We want to bring those two groups, who do not always and everywhere have a regular practice of talking to one another, into more direct and continued conversation—especially around the moment of a new acquisition or exhibition, and specifically focused on collaboratively addressing challenges associated with preservation and conservation.

Colloton: At collecting institutions, working with living artists is a very interesting and always shifting process. My first exposure to this was at LACMA, with installation documents. These can be very dense and complicated for media artworks, because there’s a spectrum of how specific the installation instructions can be and how flexible an artist wants to allow the work to be. As a technician, I had this impulse to just ask the artist to tell me what to do. What projector do you want? What resolution do you want? How big should the projection be? Just give me all of the specifics.

Ten years later, of course, I understand that’s just not how art works. It’s not what media art is. It’s not what an installation is. And that lesson—that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution—is an idea that you run into in media preservation all the time. There isn’t this list of things where, if you do this, if you do A, B, and C, then preservation is done. It doesn’t work that way.

So I’m wondering about trying to teach people about how to preserve media art. How do you come at this amorphous, one-size-never-fits-all solution? How do you broach that topic, especially with an audience that’s so hungry for direction?

Cordova: It’s such a difficult question! I would say there are two approaches for us. The first is to help people feel empowered to take on work that traditionally may have seemed a little scary. At Maintenance Culture, we encourage folks to be okay with the fact that they may not be experts in digital preservation—and also to recognize that they don’t have to be experts to attempt to do something in their organizations.

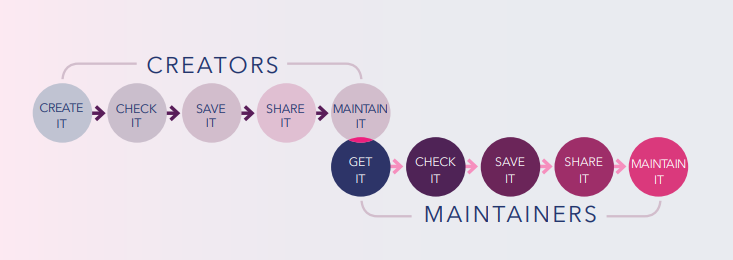

And then second, we try to give guidance and a loose workflow for this work because there is a desire for that. People are busy and wear so many hats, especially in small and mid-sized organizations, and they only have so much time. So we have developed an entry point and a framework for things that people can do. We’ve based it around an idea developed by the Sustainable Heritage Network, and boiled it down to a handy sequence or checklist of work-phases: get it, check it, save it, share it, and maintain it.

With this framework, we’re trying to provide very practical and helpful guidance—while also leaving room for flexibility, for the possibility for mistakes and the need for a learning curve and things of that nature.

Colloton: I love the framework. I think it does the heavy lifting of taking this problem that’s too big to solve and too scary to approach and makes it smaller. It makes me think of something the Digital POWRR Project has done. They have this really fun idea of, I think they call it “better than nothing preservation” or “good enough preservation”.1 Coupled with this kind of empowerment you were just talking about, the good enough preservation concept allows you to take this enormous problem and break it down into chunks. And then you can accept that you just need to take little nibbles at these different pieces. It just needs to be good enough, it doesn’t need to be everything. This unsolvable problem suddenly becomes a series of small tasks that you can take on as you need.

Cordova: That’s exactly the idea we’re trying to put out there. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. When you get your archival or conservation or preservation training, you’re taught to have a healthy fear of technological obsolescence. It’s understandable; after all, that’s why preservation matters. It’s why we need to be doing this, why we need to act—because obsolescence is coming.

But I wonder if it hasn’t also caused a bit of panic, made too many people think, “I wouldn’t possibly know how to stop it because my knowledge only goes so far.” It can even lead to a kind of task paralysis. I think the framework we have adopted can help undercut what feels like a generalized anxiety about obsolescence, in a way that feels productive.

Another idea that we at Maintenance Culture think about all the time is that you don’t have to think about preserving something forever. That’s not your job. And that’s also a bit different from what many of us learned in school, especially when working with more analog objects. You can preserve paper for hundreds of years if you put it in an acid free folder—and, wow, you’ve done something that will last for generations to come! But it doesn’t make the act of preservation any less meaningful if you’re only preserving it for five to eight years so that someone else can take up that role at that time.

Colloton: My supervisor at the Hirshhorn, Briana Feston-Brunet, has said that when you’re writing your conservation documentation, your audience is just you. You’re not carving it into a stone tablet that’s going into cold storage right next to the artwork. You’re running a relay race, and you just have to get the baton to the next person.

There has been this sort of false dichotomy in my field between video and film. Like with paper, people have thought film can just last forever, if it’s kept in the right storage vault or under the right temperature and humidity conditions. You know, you put it in a film can and put it on a shelf and you’re done—it’s preserved.

But of course that is not true. The vault needs maintenance, or the building goes under construction, and you have to move all of the cans out to put them somewhere else. A filter malfunctions, or a better filter becomes available, or everything has to be rehoused in polypropylene cans. There’s always this active, cyclical process. The preservation challenge is going to be what it is when you get to it—and then, when you’re not the one working on it anymore, someone else is going to be confronted with new challenges.

Cordova: It also gets me thinking: what is the universal entry point for folks who are involved in the preservation of time-based media or born digital creative works? Is there one? After all, someone who works in IT, are they going to have the same concerns as someone coming at it from a curatorial perspective? No, of course not.

So what’s the unifying point of entry? At Maintenance Culture, we tend to think it has to be the artwork itself. And that was reflected in our first workshop. We had a really wide range of folks in the room—there were some students, there were registrars, there were AV technicians, there were IT specialists, conservators, museum directors. Then there were people that were also artists, who worked in museums but also made art themselves. And the thing that brought all of them to the room was a commitment to the work, to the work of art itself. They were unified in their commitment to their collecting institutions and their communities. I don’t know if you have seen this, too, but it really seemed to be the driver of how we could reach everybody at the workshop.

Colloton: I think it’s fair to say that the artwork, and maybe more specifically the context of the artwork, is where conservation decisions come from. When determining what type of treatment is appropriate or necessary, that’s really best practice—starting from what the artwork is, what context it was created in, and how it is presented now.

And to your larger point: this is a thing that I feel like we don’t talk about very much in preservation, but it’s not like we come to this field because we’re fascinated by acid-free paper or something. We come to this because we love art, or because we love history, right? We might take it for granted, but we all already have this investment in the content of the work, which is why we care about the thing we are preserving.

Cordova: There are hubs where people are already congregating around this work, of course. At Maintenance Culture we’re doing what we can to build up these communities of practice. And we’re trying to do so without being imposing and all-knowing—by, for example, connecting with local professionals to identify what the needs are in a particular area, and to promote our workshops and make sure people in the community know about them. Maintenance Culture at its root is built upon these ideas of taking risks, of empowering ourselves to feel like we can tackle whatever challenges are out there. Let’s democratize this work, let’s build up communities of practice, and let’s do this work together.

Colloton: As you are saying that, I’m thinking, yes of course, media preservation is happening everywhere. But I do think Maintenance Culture’s target audience, the small and mid-sized institutions—you know, where the registrar has to take a 15-minute coffee break with the AV person to decide how they’re going to preserve their media artwork because they don’t have a full-time time-based media conservator—is a very underrepresented perspective.

We’re lucky to have resources like MoMA’s Media Conservation Initiative, or the Electronic Arts Intermix. But the field is at this place where time-based media is no longer a special edge-case or oddity. If you have an art collection, you probably have some media in it; if you have a contemporary art collection, then you definitely do. And that’s not just limited to institutions like the Smithsonian and MoMA anymore.

Cordova: I would also say that folks working in those smaller institutions, they’re already doing so much. The necessary flexibility of staff at these kinds of cultural heritage organizations is so great—it’s natural that there would be a feeling of, “Oh, I couldn’t possibly do more!”

Some of what we’re doing, especially with the field guide we are publishing2 , is meant to bolster the case for staff at these institutions getting the support they need. So when people need to get their institutional stakeholders on board to invest in a conservator, or even to hire a project conservator, they can point to what we’ve put together and say, “Look, this is a growing field, we need to be doing this too. Here’s all the work that we need to be doing, here are the resources we need, here are the tools. It’s all laid out for us, so let’s get going.”

Here’s a question for you: what do you feel is possible for folks with more limited resources and without a degree from NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation (MIAP) or experience at a place like the Hirshhorn? What can empower people and feels appropriate and achievable—without running the risk of undermining the field of conservation?

Colloton: Thinking in terms of starting points, anybody can make an inventory, anybody can fill out a spreadsheet with, say, how many videotapes they have. And I mean, most videotapes have what they are written on them! So you can make a list of what you have, and be pretty technical about what it is, without a whole lot of technical expertise. The same is true for digital media—how much do you have and what is it? Those are huge questions to have answered, and once you know that, all your next steps stem from there.

Cordova: What about collaborations with the artist? Artists are really the experts in some ways—how can they be a resource?

Colloton: Well, there are certain things the artist is going to know way better than anybody else, right? That’s something I took away from the VoCA Artist Interview Workshops. With artist interviews, more than simply having a checklist of questions, it’s really about getting an understanding of the artwork and where the artwork came from and the production history of the work. And that gives you so much information about the materiality of the artwork and what its dependencies are. Why is it a VHS tape, or why is it a digital video file? Why did the artist choose H264 instead of uncompressed? If the artist is living and available, they can tell us a lot about what a given work is and how it got here.

Cordova: And obviously, not all artists are the same, but I find that time-based media artists tend to be incredibly flexible. In most cases they know that their piece might have to migrate—I mean, they’re working in ephemeral technologies, sometimes on purpose. So they have a sense of what the essence of the work is, and what it would mean to show the work at another point in time.

Often, actually, it’s the artist more so than the archivist or the conservator who recognizes the freedom and flexibility in the medium. It’s why they work in media art.

I was reading an old interview with Corey Arcangel, and he’s makes precisely this point, says something to the effect of, “Yeah, of course it’s going to be on something else. I know.”3 And that there was something liberating about that. So again, if you have access to an artist, and they are actually quite flexible and live in that ephemeral space on purpose, then it can be quite freeing for an archivist or conservator, too.

Colloton: Joanna Phillips, a time-based media conservator, has written about this. She has an article about an artwork being young and growing into itself, and about avoiding the impulse to prematurely fix an artwork into a particular parameter.4 About allowing it to grow and mature, as opposed to saying, “Well, this artwork’s been installed once, and so now every installation of it must be the same.” I think often when artworks enter contemporary art museum collections, they’re not totally fixed yet. And having the artist in the conversation is a good way to keep that perspective, to maintain this idea that it’s still flexible, it still has room to grow.

Cordova: Sometimes it seems so obvious, but dialogue and collaboration are really everything. They are really what make possible the sort of work Maintenance Culture is trying to do in these types of settings.

Colloton: That resonates with my experience in the conservation community, too. Going to all these conferences and symposiums and events are really great ways to get these problems out of your head. And before you know it, a conversation with other people suddenly shifts where you’re stuck or gives you a new perspective on where you are with a set of problems. And also just makes them feel less individual, right?

Cordova: Totally.

Colloton: Hearing other people say, “Oh, I had that same issue,” or “Oh, I ran into that same thing,” like we were talking about earlier, makes the problem feel smaller. Suddenly it’s knowable or quantifiable. Or there was one time when I was up against a challenge and really feeling like I had no idea what to do about it. And I was talking to somebody else who was further along in their career, and they were like, “Yeah, I don’t know either.”

Cordova: Getting that reassurance that you are not the only one in this boat.

Colloton: Yeah, exactly.

Cordova: What a relief to know that someone who’s been doing the work before you also didn’t quite know the answer! I think we all have a little bit of that imposter syndrome. There is this desire to only want to talk about or do something when you feel like you’ve already mastered it. I’m exactly the same way, and I think it’s so common.

At Maintenance Culture the idea is that we don’t have to do that—sometimes, you don’t know the answer. I mean, there is expertise, and there is knowledge to be shared, of course. But sometimes it’s just nice to get people in a room where they can admit to each other that they’re still figuring it out, that they don’t always get it right, that they make mistakes sometimes. There is power in communities of practice, or what media conservators might call networks of care. We’re seeing that play out and it’s really energizing.

1. Schumacher, Jaime; Thomas, Lynne M.; VandeCreek, Drew; Erdman, Stacey; Hancks, Jeff; Haykal, Aaisha; Miner, Meg; Prud’homme, Patrice-Andre; and Spalenka, Danielle, “From Theory to Action: Good Enough Digital Preservation for Under-Resourced Cultural Heritage Institutions” (2014). Faculty Peer-Reviewed Publications. 1056. https://huskiecommons.lib.niu.edu/allfaculty-peerpub/1056

2. Link to be added when available. Stay tuned!

3. Crystal Sanchez and Claire Eckert, “An Interview with Corey Archangel,” Smithsonian Institution Time-Based and Digital Art Working Group: Interview Project, July 7, 2013, https://www.si.edu/content/tbma/documents/transcripts/coryarcangel_130707.pdf

4. Phillips, J. (2012): “Shifting Equipment Significance in Time-Based Media Artworks,” in: EMG Review, Vol. 1, AIC Publications, Washington D.C., pp. 139-154. http://faic.wpenginepowered.com/emg-review/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2016/07/Vol-1_2010_Ch-6_Phillips.pdf

Main image

Brainstorming at the Maintenance Culture Charrette

Baltimore, MD, 2022

Photo by Emily Twines

Image description

A photograph of a large white piece of paper, divided in different sections and covered in writing. This writing consists of miscellaneous words and short sentences, written in green, orange, and purple marker, in the style of a brainstorming exercise. Four words are written in black marker and have red hearts around them: “Get”, “Save”, “Check” and “Share”. On the top right corner, a hand can be seen writing with an orange marker.