On the edge of night

The Standby Program

In the mid-to-late 80’s, New York was a significant crucible in pioneering new technology for the nascent form of video art. Media centers and artist-run organizations were mushrooming across the state: The Kitchen, Visual Studies Workshop, Young Filmmakers (later Film Video Arts), Experimental Television Center, DCTV, and The Center for Media Study SUNY Buffalo, among others.

This trend was driven by technological advances, cable community access TV, public television, MTV, and the perspicacity of a new generation of curators. As cameras and video recorders became cheaper, and video formats became smaller, opportunities to screen and broadcast independently produced tapes became more and more plentiful. Yet the ability to record images and sound had quickly outpaced the ability to shape it; that is, video production surpassed video editing and, in the process, couldn’t always adhere to the highest technical standards necessary for broadcast. While the tools and shooting formats became cheaper and more accessible, the editing equipment and the time needed to do it remained expensive1 and required a steep learning curve. A sampling of technical terms from that time—LTC, VITC, drop frame, non-drop frame, dropout, EDL, sync generator— remains just as inscrutable today as it did then.

One could think of an artist with a paintbrush, a chisel, or a chain saw, yet it strained the imagination to think of the artist in frigid, air-conditioned broadcast suites, huddled over computer keyboards, surrounded by dozens of video screens. It was in 1983, in an enormous television studio named Matrix Video2 located on the edge of Hell’s Kitchen’s western frontier, that one of the most significant outposts for the creation of video art emerged. It was there that the Standby Program first made its home.

I learned about the Standby Program sometime in the spring of 1984. I was in my apartment in Madrid, and the Spanish artist Antoni Muntadas handed me an oddly folded brochure. I remember taking the flyer in my hands, opening it very gently. There was a strange, scientific machine on the cover, a reticule of a vectorscope or a waveform monitor, and a description of Standby’s services. I vaguely knew about the program, having seen some of their visually stunning tapes at the San Sebastian video festival the previous year. Muntadas urged me to meet this guy Alex Roshuk on my next visit to New York.

That summer, I returned to New York, and after a flurry of messages left from pay phones, I finally connected with Alex who invited me to his apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn. He greeted me at his door, books and piles of papers spilling out, his showman’s sense and larger than life character embodying Stanley Kubrick and Orson Welles. In his crowded office, on top of a speaker, perched a broadcast television monitor and a U-matic deck. Waving a U-matic tape in front of my face, he popped it into the deck and regaled me with an extraordinary sampling of videos produced through Standby: Dara Birnbaum, Ardele Lister, Juan Downey, and Edin Velez.

Dara Birnbaum, Damnation of Faust:Evocation, 1983

Video, color, sound, 10:02 minutes

Courtesy of the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

The Standby program, then not even two years old, had grown out of a dream of Rick Feist and Alex Roshuk, who met when they were film students at Princeton. Rick had been living in Berlin, where he was an editor at a facility that permitted artists access in the studio’s off hours. On his return to the U.S., he reconnected with Alex and both of them tried to translate that idea to New York. Alex was a filmmaker, who had been developing the 185 Corporation, a non-profit arts organization devoted to helping local artists.3 Rick’s idea of providing access to broadcast video editing was a natural extension of the organization’s mission.

What set Standby apart from other media arts centers was the fact that it didn’t have the expense of owning and maintaining a building or costly equipment often needing upgrades. Instead, Rick and Alex came up with a model of resource sharing that provided the arts community extraordinary access to the private sector, by partnering with one of the largest broadcast television studios in Manhattan.4 Matrix Video had two large sound stages, an insert stage, two tape rooms, two audio suites, three video editing suites, and a mobile truck.5 Rick and Alex proposed to rent the editing facilities at significantly reduced rates to artists and independent filmmakers at night or on the weekend when the facility was dark. They also proposed that artists could be bumped if commercial work necessitated that—hence the name Standby—and chose a one-inch videotape machine standby button for their emblem.

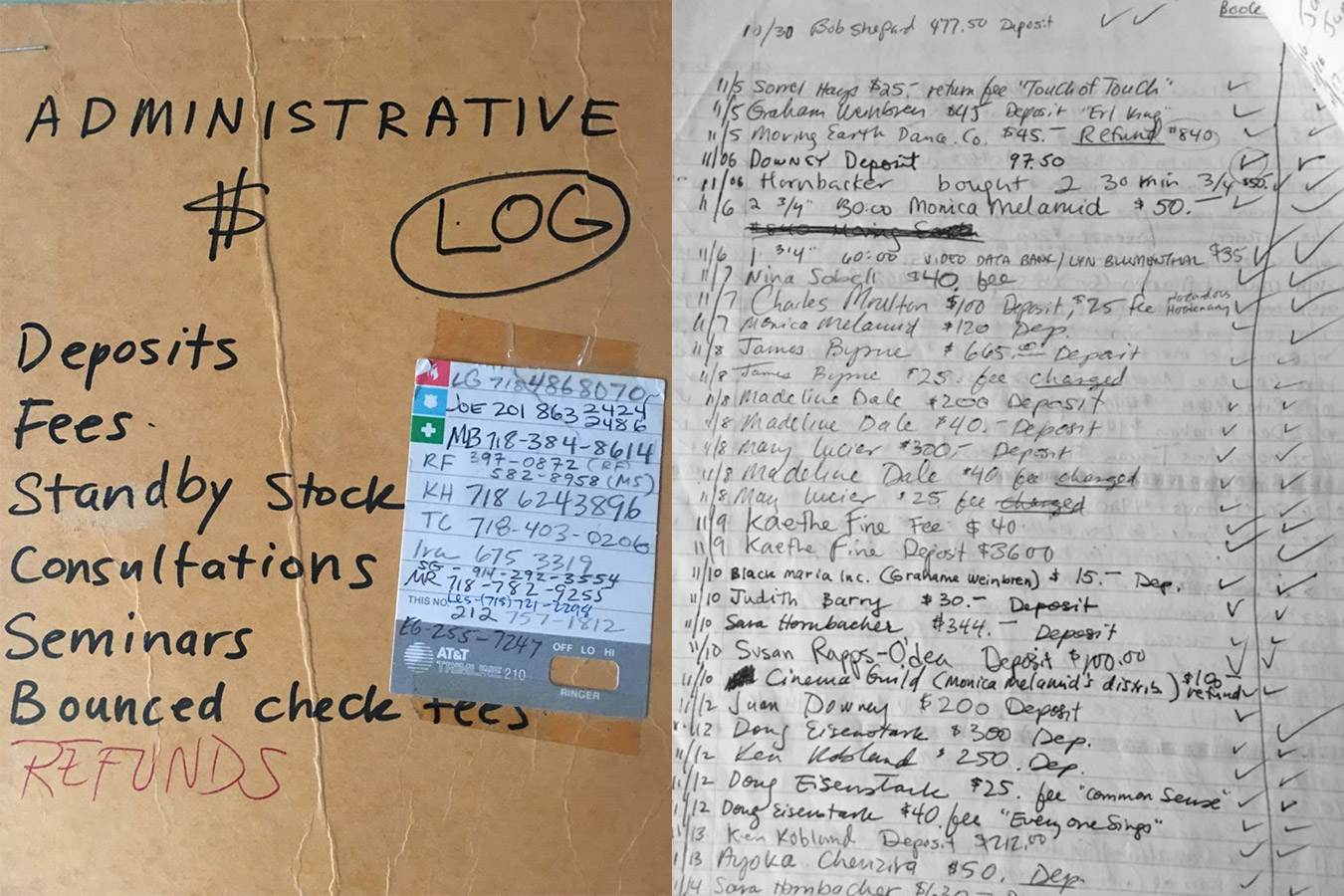

Alex and Rick also negotiated with Matrix’s owners to buy time as a non-profit. They would certify that the projects they booked were non-commercial, made by artists and independent filmmakers. By requiring artists to pay upfront before the sessions, Standby was able to pay Matrix weekly. This was a financial boon to the studio, whose facilities and upkeep cost millions of dollars and whose cash flow was always tight. Still, the sight of artists with unconventional ideas traipsing around the studio was, to put it mildly, somewhat off-putting for the studio’s more conservative engineers.

If Alex had the aura of a showman, Rick had the intensity and focus of a renegade computer hacker. In those days, he dressed in jeans and a black leather motorcycle jacket, his hair tied tightly in a ponytail and a cigarette always at the ready. During edit sessions that lasted hours, he would sit intently in front of the CMX computer console, conducting the flow of images, the screen of scrolling illuminated numbers brightly reflected in his glasses as he twiddled the joy stick of multiple channels of the Ampex ADO.6

For artists, using Standby was something of a ritual and rite of passage. You never quite knew if you were going to be bumped, or if the edit would even happen. Throughout the day you would sit patiently by your phone to hear some word, which often didn’t come until quite late. As the filmmaker and artist Shelly Silver recalls:

It was like 11 pm, 11:30. You were all packed up. You were waiting at home. You get into a cab. You go to this neighborhood that at that point was really an awful, awful neighborhood. It was in the west 50’s all the way west. There was a park across the street where people were always getting murdered or beat up.7

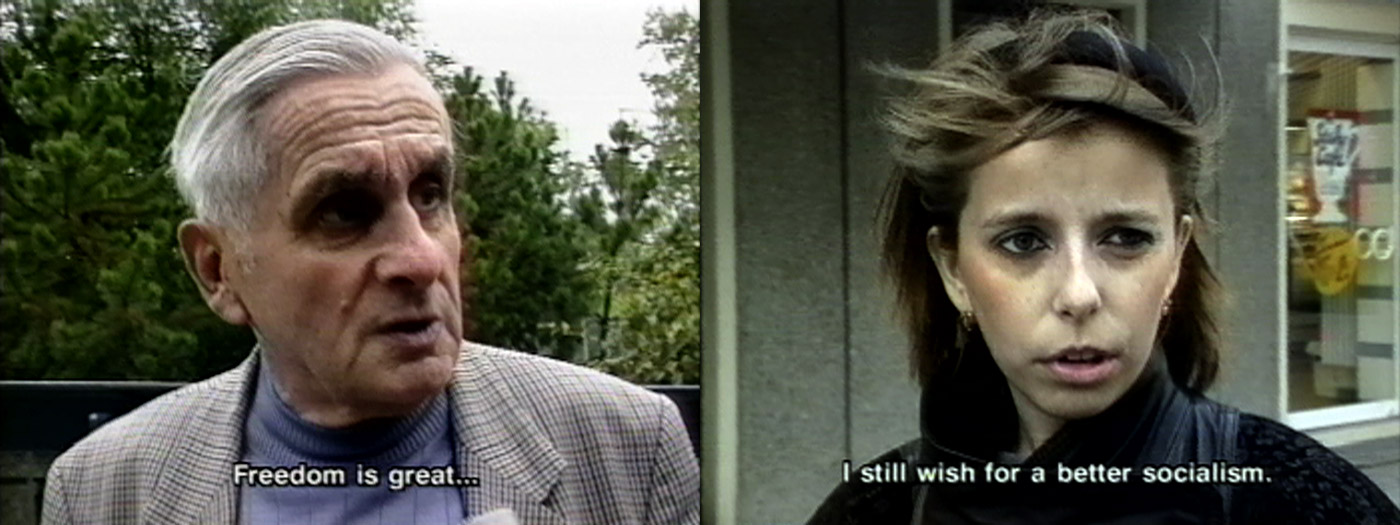

Shelly Silver, Former East / Former West, 1991

Video, color, sound, 65 minutes

Courtesy of the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

The whole thing had an illicit feel. Entering Matrix was like entering another world on the fringes of a high-tech, electronic frontier. It was totally dark inside. Machines whistled and hissed; any light blared harshly, practically blinding you. This alien and foreboding environment really was more like a colossal time machine that shifted days into nights and nights into days, when the sessions would often last until dawn. Shelly continues: “In the back was the magical room, the one room that I would get to work in. It was this really enclosed special atmosphere. No one else was around and it was sort of like the kids were taking over the candy store.”8

The work was intense. When given permission to edit in a broadcast studio, artists’ eyes opened to new ways of making the moving image. Ardele Lister’s Hell, for example, produced in 1985 and inspired by Dante’s Inferno, pushed broadcast technology to the extreme. According to Lister,

It was like being in some kind of locked connection with one another and with the technology. I spent a lot of time in the edit room through Standby exploring using some of the concepts of Dante’s. You know, like in Hell there are no illusions, and video is all illusions, how would I work with that? Standby was revolutionary for me.9

The program’s very first editing project, Juan Downey’s Information Withheld, took over three months to finish, and Standby quickly grew from there. Downey and Feist developed an exceptional friendship and working relationship. They edited the three subsequent tapes of The Thinking Eye series together, works that remain integral in the video art corpus and are exemplary of what could be possible at Standby.

Kathy High marked a new phase when she joined the program in 1985. A respected video artist, now Professor of Art at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and co-editor of The Emergence of Video Processing Tools,10 she had studied at The Center for Media Study in Buffalo, and had worked at Hallwalls as well as Video Data Bank. She brought an expanded perspective linking Standby to the experimental video practices of Woody and Steina Vasulka, founders of the Kitchen, who helped start the Center for Media Study. She also incorporated the radical aesthetics of filmmakers Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits, who taught at SUNY Buffalo. When asked what these parallel approaches to art and technology were like, she said:

I moved to New York City in 1983. Coming from Buffalo, the aesthetic was more DIY, more build it yourself, like the Vasulkas who were working with engineers to design custom equipment to make their tapes, or Tony Conrad who was always tweaking things for his projects. My education in Buffalo really made me interested in technology and made me want to get my hands on it. The model of the production center I described and Standby were different models, what we used to call “state of the art” technology. Standby was a little more tied into television as an outlet and as a distribution model. That was a new model in the 80’s, there was a lot of funding to put video artwork on TV at that time, unlike today.

When Rick approached me to work with him at Standby, I was the scheduler and handled the artists’ deposits to pay for their edits. What mostly interested me was that Rick also said I could be trained as a CMX editor and I thought, oh wow. It was kind of like flying a plane.11

By 1985, Standby had added an operations manager and three video editors: Tom Crawford, Lisa Guido, and Kathy High. Matrix donated office space, and offered to house the more than 600 one-inch video masters produced through Standby in the Matrix tape library. 155 projects by 101 artists were edited at Standby in 1987.12 The program continued to maintain this level of activity over the next five years, even after Matrix closed in 1989, when the program was forced to move to Editel NY, Unitel, and other facilities in Manhattan, where the work continued.

When I joined Standby in 1987, first as an apprentice editor and then as an online editor, access was becoming more important than ever. The staff of editors and assistant editors had doubled facilitating over 700 edit sessions totaling almost 3,000 hours.13 The program was presenting seminars on post-production. Feist began writing a series of eleven technical articles published in the Independent magazine from 1989-1992 entitled What The Manual Didn’t Tell You. Lisa Guido was very much behind this push: “I think the seminars are a really important part of Standby for the development of the artist, to know how to use this great thing that’s before you. Here’s a professional television studio, here is all of this equipment. And how do you even begin to speak the language?”14 Jem Cohen was also among those filmmakers who edited several tapes at Standby:

Having the grain be what I wanted it to be, or tinting black and white footage a slightly interesting shade of green, and having it stay that way from monitor to monitor. Those things weren’t trivial. If you had a certain quality in the original material and you wanted to maintain it, that’s how people would get lost in the work, if that black was really black. Being able to get ahold of these tools that you couldn’t afford to use normally. Plus, having people that you could work with who understood what you were after. That process was tremendously important. And I don’t know what I really would have done without it.15

Standby didn’t just excel at formal innovation. It became key to expanding documentary production, especially in pioneering the use of consumer formats for broadcast editing. We established the workflow facilitating the use of VHS, Betamax, 8mm and Hi8 videotapes for broadcast. Remarking on the impact of Standby on the creation of his work, Grahame Weinbren (who edited the interactive cinema work Erl King there with Roberta Friedman) said:

The secret and hidden influence that Standby had on the medium and the art form is unrecognized. Standby gave artists access to the most advanced video technologies and I am forever grateful for being able to free my mind to imagine possibilities that the constraints of the time-is-money world would have cut off at inception. We could experiment with these expensive instruments in ways that few people could. It’s like one of those butterfly effects: a small change reverberates through the whole culture. The effect Standby had on the development of video and audio media is barely recognized, but I believe it is enormous.16

The Standby of today began taking shape in 1989 when I first met Bill Seery in the halls of Matrix as he was setting up a sound studio there. He gave me a tour of his suite, and expressed a keen interest in providing audio services through Standby to artists, having worked formerly as an audio engineer at the downtown artist-run studio Harvestworks. The involvement of Seery’s Mercer Media17 greatly expanded the range of post-production services Standby could offer.

By the early 90’s, Standby had become a mainstay for finishing independent work. It had reincorporated as its own 501(c)3 and expanded its funding from government sources such as the New York State Council on the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and New York City Department of Culture to private foundations, the John T. and Catherine D. MacArthur Foundation, and the Andy Warhol Foundation among others. Later in the decade, the New York City film and television industry began changing drastically. Large, multi-service studios catering to advertising and commercial films started going out of business, a byproduct of the advent of computer desktop digital editing. Seery turned this into an advantage by acquiring broadcast equipment at auction, which he grew into an array of legacy videotape machines to migrate analogue and digital video and other magnetic media to current codec’s and formats.

Standby Executive Director Maria Venuto and Seery expanded into the field of media preservation, with the aim of conserving the works of many artists and the cultural history of organizations like ACTUP Oral History Project, Appalshop, Experimental Television Center, Franklin Furnace, La Mama, Martha Graham Center, and Paper Tiger Television. Standby has also done extensive preservation work for exhibitions at MoMA, the Whitney Museum, Artists Space, the New Museum, Albright Knox, and Dia Art Foundation. For Venuto, the preservation program is a natural extension to Standby’s original mission:

When I saw our program users seeking to preserve their media work, I felt Standby was in a unique position to help them in the preservation of their moving image, audio, and time-based media artworks. We could provide collection evaluation, cleaning, migration, digitization, and restoration of artworks on “at risk” video formats. Our preservation program is a partnership with Mercer Media, a private sector facility. This unique model of operation enables us to provide highly specialized services while avoiding the purchase and maintenance of equipment required to perform preservation work.18

If the concerns of the 80’s and 90’s were about access, about getting your hands on production equipment, about editing, distribution, and screenings, the shift to preserve this work now indicates just how successful those strategies were. And just as it was thirty years ago, when media arts centers and service organizations like Standby were dedicated to production, they have shifted their focus to preservation as post-production tools have become more accessible and within reach of artists and independent filmmakers. It’s a continuation, really, in line with how Standby first started. Those seemingly never-ending nights on Eleventh Avenue and West 52 Street, in the darkened chambers of Matrix Video, of which Rick Feist once said:

It was about experimenting, trying to innovate and to create something that expressed something more personal, something more alternative, something more hopefully of value. Thomas Pynchon had an idea about Slothrop in Gravity’s Rainbow, where he said that Slothrop had the ability to dream other people’s dreams. I always identified with that, spending my nights with video artists, getting to know what their dreams were.19

1Editing technology was largely a costly byproduct of the microcomputer revolution.

2 This site is now the home of The Daily Show.

3 The 185 Corporation was named after the address of the Princeton art department, 185 Nassau Street, where Rick and Alex both hung out as students. It grew out of the idea of an artist collaborative, an alternative non-commercial activity of Madison Smartt Bell, Neil Cartan, Rick Feist, and Alex Roshuk, recent Princeton graduates living in South Williamsburg, Brooklyn in the early 1980’s.

4Rick had started working at Matrix Video as a videotape operator at the suggestion of another Princeton college friend the photographer Andrew Moore whose cousin Bobby Lieberman was the head engineer. Alex also served as a board member of Media Alliance. Robin White, its Executive Director had developed a similar program to Standby called the Online Program providing access to broadcast television studios.

5 The theater director Robert Wilson shot and edited his one-hour long broadcast video Stations there the year before.

6 Ampex Digital Optics (ADO), one of the first digital video effects devices that manipulated video images in 3-D space.

7 Shelly Silver, in discussion with the author, 2003.

9 Ardele Lister, in discussion with the author, 2003.

10 Jimenez, Mona, Kathy High, and Sherry Miller Hocking (eds), “The Emergence of Video Processing Tools,” Intellect, 2014.

11 Kathy High, in discussion with the author, 2018.

12 Standby statistics for 1987, 1991.

13 Standby statistics for 1987, 1991

14 Lisa Guido, in discussion with the author, 2003.

15 Jem Cohen, in discussion with the author, 2003.

16 Grahame Weinbren, in discussion with the author, 2003.

17 Named Mercer Media because Seery’s first sound studio was on Mercer Street in Soho, next to Fanelli’s Cafe.

18 Venuto, Maria, Standby Preservation Program description, 2018.

19 Rick Feist, in discussion with the author, 2003.

Main image

Jem Cohen, film still from This Is a History of New York, 1987

Super 8 film edited on 3/4” Umatic, 23 minutes

Courtesy of the Artist