No Artist Is an Island

Oral History and the Relational Archive

Over the course of their careers, most artists interact with thousands of people and scores of institutions. Evidence of their legacies is fragmented across culture and society. Much of the work of the staff and leadership of artist endowed foundations is devoted to gathering the scattered documents of “their” artist and organizing and collecting them in an archive and database.

Such systems have typically supported individualistic projects such as retrospective exhibitions, biographies, and catalogues raisonné. For generations these productions have represented the capstones of a successful career and been requisite for entry into, or maintenance of, the art historical canon. Despite the inherent interconnectedness of artists’ lives, the conventional structure for information architecture has remained the “hub-and-spoke,” with the artist at the center and all related materials, individuals, and institutions radiating outwards, nodes disassociated from each other.

This monographic model no longer fully serves the current imperatives of decentered and revalued art histories, which create new spaces for historically underrepresented artists. The ontological shift from the autonomous to the heteronomous and from the hierarchic to the rhizomic has necessarily compelled artist endowed foundations and other entities devoted to individual artist legacies to expand their thinking regarding missions and redeploy resources so the foundation may serve as a platform to elevate other artists and open points of access for diverse communities. While these initiatives are most visible in the format of grants, educational programs, and other public activities, they also occur within the context of internal procedures. The simultaneous emergence of new ethical frameworks in art history and interactive digital technologies have inspired a radical shift in cataloguing and archiving toward shared authorship and institutional collaboration. No artist is an island.

When I joined the Al Held Foundation in 2016, I first assessed the degree to which the resources stewarded by the foundation qualitatively documented Held’s participation in the networks of the modern and contemporary artworlds across his fifty-year career as an influential abstract artist and professor in the Yale School of Art. Though the foundation possesses a substantial archive composed of Held’s papers augmented with copies of professional records from public archives, stored in his former home and studio in the Catskill Mountains, there are scant first-person written records that illuminate his myriad personal and professional touchpoints. Held typed or handwrote precious few documents. Instead, he was a talker—“the conversant artist,” according to The Brooklyn Rail.1 Held’s dialectical mode of discourse about art and politics shaped his public persona and left a strong impression on artists, students, friends, and family. He discussed intellectual, aesthetic, and personal matters in the flesh or on the telephone for hours, but unlike Warhol, he did not tape his conversations.

Because of the preeminence of the spoken word in Held’s educational and professional development and identity, oral history has been an essential tool to build a body of primary source materials that contribute multiple perspectives to the foundation’s expanded archive and knowledge base. I have pursued this on two tracks. The first has been obtaining recordings of Held’s voice not already in the foundation’s archive. Thanks to the cooperation of librarians and archivists not directly responsible for his legacy, the foundation acquired previously unknown recordings of private interviews by Irving Sandler in his papers at the Getty Research Institute and public lectures by Held in the archives of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and Reed College, among others. The second pursuit has been an oral history program, inspired in part by those of the Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg Foundations, to interview Held’s artistic peers, family, studio assistants, students, and others who knew him well. Together, they have formed a relational, collaborative archive enabled by the participation of others whose voices and memories might not otherwise be documented.

These efforts were bolstered by the VoCA Artist Interview Workshop I attended at the Museum of Modern Art in January 2019. It provided intellectual and methodological frameworks to facilitate the interaction of oral history and archive. Oral history is not a linear excavation, but a shared construction of a robust, living document built on memory, trust, and concerned interest, along the lines of Columbia University history professor Saidiya Hartman’s practice of “intimate history.”2 Hartman developed her scholarly method to address historical power imbalances and the absence of first-person archival records of Black women. Her intersubjective method of interrogating the archive can be respectfully adapted, even within the privileged legacy of established white male artists, to create spaces and elevate voices that might otherwise not have been preserved. VoCA Workshop presenter Thomas Lax summarized this best when he called his curatorial practice “a discipline of care” with a sense of responsibility to recognize and safeguard untold or unheard stories.3 The VoCA approach to the stewardship of modern and contemporary art, as I understood it, emphasizes the formation of partnerships between arts professionals and interviewees, beginning with the pre-interview and extending through any number of encounters. Workshop leaders Jen Mergel and Sam Redman called for a deeper engagement with past and potential interviewees, inspiring me to revisit conversations that I had considered concluded and to approach a far larger number of people with varied perspectives on Held and his world. I endeavored to apply the key takeaway that oral histories are not one-off events, but ongoing processes requiring open access records and metadata.

The Al Held Foundation’s oral history program began as a journalistic interview project focused on extracting information to corroborate and inform Held’s official biography. After I attended the VoCA Workshop, it morphed into something completely different: a larger and more relational archive in which multiple participants shape its scope and contents. In short, the project began to take on a life of its own and exceeded the initial parameters. However enthused, I also proceeded cautiously in incorporating newly collected stories and information into existing narratives about Held and his work, cognizant that each oral history bears a unique perspective colored by selective memory, feelings, and attitudes that sometimes diverged from Held’s recorded statements and personal histories. In some cases, subjects took advantage of the interview as an opportunity to expound on their own experiences. And at other times, interviewees resisted delving into politics or personal life, hesitant to commit potentially discordant memories to an archival audio recording. As much as possible I aimed to create a relaxed situation where interviewees could speak freely, reassuring them that they would not be published without their permissions, and their unique perspectives were essential to an ongoing process. Reassured that they would not bear the burden of the last word on any subject, interviewees generously shared photographs, correspondence, and publications that enriched the context of the oral history and expanded the foundation’s archive.

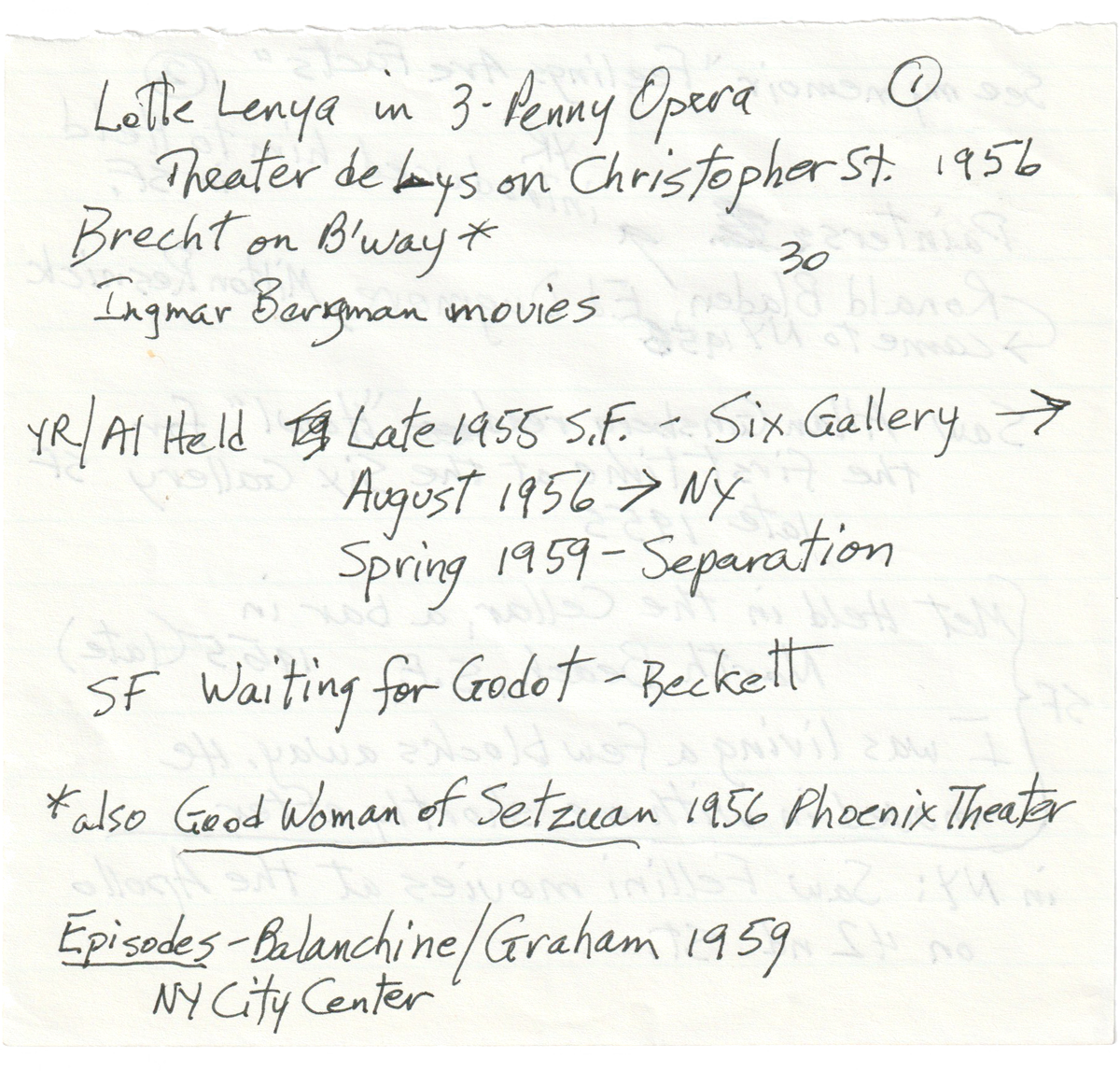

In some instances, the interviews were with well-known artists with their own public archives and legacies. Such is the case with dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer, who was partnered with Held for four years (1955–1959). I had interviewed her by phone prior to attending the VoCA workshop, but found the results unsatisfying. In my old, Held-centric perspective, I approached her chiefly as an eyewitness to his mid-1950s painting practice. Accordingly, I focused my questions on their first year together in San Francisco, of which the foundation possesses scant documents, hoping to jog her memory about the imagery and materials of his work, to fill some gaps in knowledge about his artistic development. With such a tight frame of inquiry, the conversation did not evolve to allow for reflection and interpretation. Encouraged by the VoCA training to revisit interview subjects, I emailed Rainer to set an in-person meeting for an open-ended conversation. She chose the location, a diner on 23rd Street in Manhattan, several blocks from the loft in which she and Held resided, across Fifth Avenue from the Flatiron Building. And she brought a handwritten aide de memoire with a list of plays, films, dances, and other cultural activities they pursued together which nourished her formative creative years. This record of their mutual exposure to Brecht, Beckett, and Bergman also affirmed the existentialist philosophical underpinnings of Held’s painting of the period. At the end of the interview, she presented the document, which is now part of the foundation archive, joining other Rainer materials including color photographs of one of her earliest forays in dance and their Mexican divorce papers from 1962.

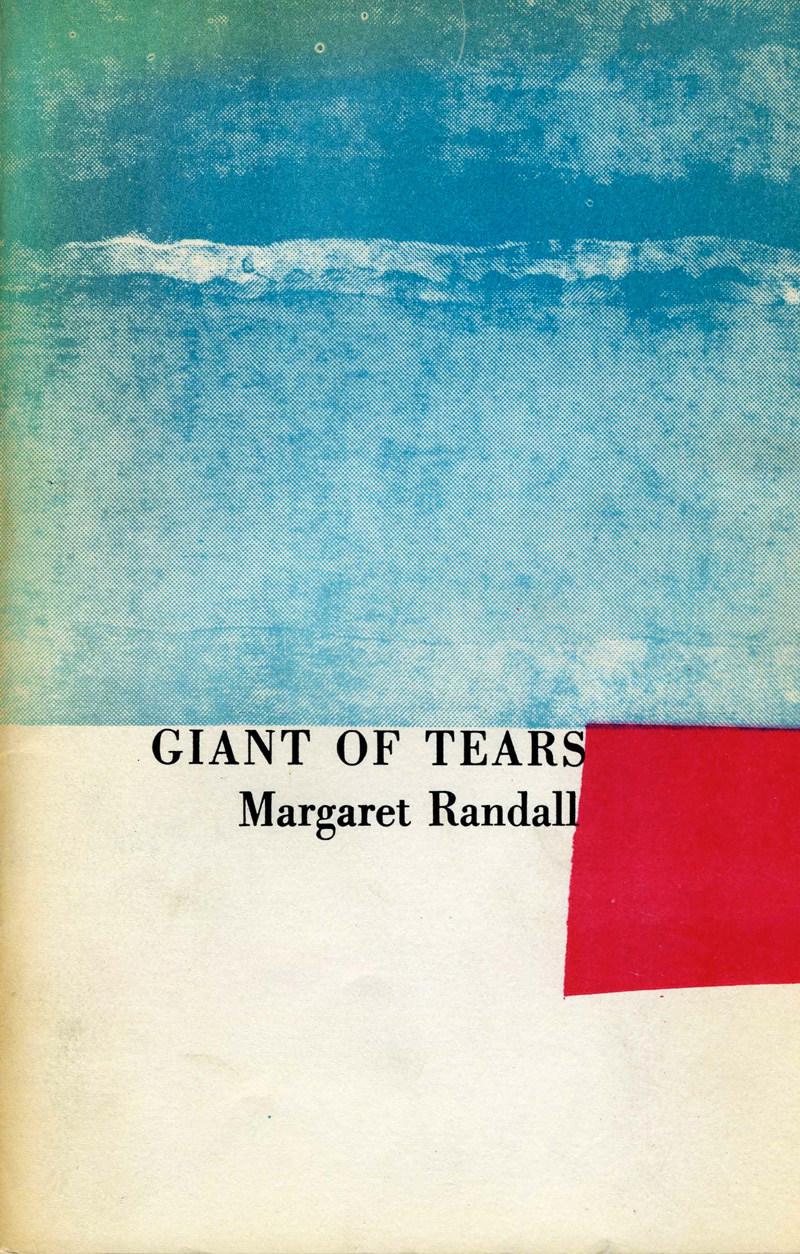

Rainer also shared revelatory information that was not previously known to anyone at the foundation or documented in the archive. Between Held’s relationship with Rainer and his next wife, Sylvia Stone, he had a brief romance with poet Margaret Randell. A prolific author and editor, Randall quickly responded to a message submitted through her website. Though only with Held for a few months when she lived in New York in the late 1950s, she readily agreed to a phone interview and shared a few charming stories and also directed me to another important reference. Her first book of poems, Giant of Tears, 1959, with a cover of her own design, also included black and white illustrations by some of the Abstract Expressionist friends in her circle, among them Elaine de Kooning, Milton Resnick, and Held. This book was unknown to the foundation, and its illustration of his India ink drawing was one of his first publications. At the time we talked, Randall was about to publish a new memoir in which she recalls the salubrious attention of older artists involved in the cooperative galleries on Tenth Street. “That generosity of spirit is something I learned in that world. I have tried hard to carry it forward,” she wrote.”4 Randall’s voice was added to the constellation, and her interview drew new links between Held and other painters of his generation.

Family members have also served as critical sources to the archive. Thea Storz, the daughter of Held’s younger sister Roberta Held Weiss, his only sibling, is a photographer and artist. Some prints from her series of color photographs documenting the extended Held family in the mid 1980s are in the foundation archive. It was known that Storz had a trove of family papers and photos, but they had never been examined. On a cold February visit to her home in northern Vermont, she brought out several boxes of photographs, correspondence, and ephemera. They contained some of the papers of her grandmother Clara Held, Al’s mother. Most of the correspondence related to Roberta, but one box contained the rarest of the rare, several handwritten notes from Held. The most historically important discovery was a postcard depicting one of Van Gogh’s sunflower paintings inscribed with a Mother’s Day greeting and mailed when Held lived in Paris, one of the few extant documents of his formative period as a student and young artist there in the early 1950s. Not just a pretty picture, the image possessed powerful symbolic value. Held recounted in interviews that the only works of art he ever saw growing up were the set of Van Gogh reproductions framed on the walls of his working-class family’s apartment in the Bronx. Storz donated the postcard along with other pieces of correspondence to the foundation and permitted scans of dozens of photographs, which bolstered the presence of the extended family within the archive while corroborating details from Held’s own oral histories.

Al Held, postcard to Clara Held, 1952, verso & recto

Offset print on paper, 5 3/4 x 4 1/8 in.

Al Held Foundation Archive

The success of a collaborative approach to building archival collections depends on developing open-ended partnerships with individuals with varied personal and family connections to Held who also intersected with his development as an artist. However, it also revealed the inadequacy of the foundation’s Embark database. Typically used by museums, this art object-oriented database is sufficient for tracking the acquisition, treatment, and disposition of works of art in a collection, but it does not permit the entry of archival and bibliographic records as discrete elements with the same status as art object records. This non-relational, hierarchical database was unsuited for queries such as those from a researcher from the Sam Francis Foundation seeking archival materials related to Francis. The two artists had a close friendship in the 1950s and 60s, sharing studios in Paris and New York. To fulfill this request, the Held foundation’s archivist Chad Ferber gathered materials indexed across Word document finding aids, Excel spreadsheets of inventories, filing cabinets, and folders of digital images stored on a server disconnected from the database. These discrete silos inhibited synthetic, substantive research across our collections.

For the archive to become relational, the foundation developed a new FileMaker that incorporated the artwork data and images from Embark and designed new data tables for archival, bibliographic, individual, and institutional records. As part of our research phase, the archivists and catalogue managers at several foundations, including Dedalus, Helen Frankenthaler, and Joan Mitchell, generously permitted us to open the hoods and kick the tires of their relational databases so we could learn from their best practices. Our new database endows all records equivalent status and sustains a lattice of relationships independent of association with Al Held. The hub-and-spoke model no longer sufficed, and was replaced with a constellation of connections that wove the singular artist’s oeuvre and biography into the larger fields of modern and contemporary art and culture. Further, the database permitted the newly collected oral histories, transcripts, and related documents to be properly processed, tagged, and retrieved for future scholarship.

As the field of artist endowed foundations grows larger and increasingly integrated with local communities and the international artworld, there will be increased needs for foundations to open their archives, and for major archival repositories such as the Getty and Archives of American Art to permit digital access to diverse materials. The Al Held Foundation, like many of its larger and smaller peers, has greatly benefitted from the professionalism and magnanimity of the staffs at numerous institutions, and the care provided by individuals who share their memories and in some cases documents and images. Just as artists form collectives and cooperatives to provide mutual support outside of the market and academy, the organizations charged with the stewardship of their legacies have found it productive to work collaboratively. The Aspen Institute’s Artist-Endowed Foundations Initiative is the largest and best-known clearinghouse and meeting ground, but panels, symposia, and research on decolonizing the archive and expanding access to documentary materials are proliferating, from the Expanded Archives Network to the Association of Art Museum Curators. And new collaborative models can be found in the Duchamp Research Portal, an international partnership of three museums and research institutes, and the Library of Congress’s crowdsourced transcription endeavor By the People.

The incorporation of diverse perspectives and materials into the Al Held Foundation archive through the oral history program also corresponds to Held’s views of his studio practice. In the mid 1960s, he emerged as one of the first postmodern painters in American art, rejecting the modernist orthodoxies of flatness and opticality as the only valid criteria for significance and quality. Held’s later abstract paintings elaborated his readings in chaos theory, string theory, and mathematical proofs of the multiverse. These vibrant images of complex geometrical structures visually represent his interest in the simultaneous existence of multiple contradictory truths. In this regard, assembling the broadest possible array of narratives, documents, and objects from multiple perspectives in the foundation’s archive reflects the spirit of Held’s own aesthetic position and his place in the world. It’s still a work in progress.

1 “Al Held: The Conversant Artist,” The Brooklyn Rail, March 2016.

2 Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, New York: W. W. Norton, 2019.

3 Author’s notes, VoCA Artist Interview Workshop, Museum of Modern Art, January 17–18, 2019.

4 Margaret Randall, I Never Left Home: A Memoir of Time and Place (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 109.

Main image

Mike di Rado and Al Held in Held’s West Broadway studio,

Torquad II and Pan North VII in progress, 1986

Courtesy Al Held Foundation

Photo: Mike di Rado; Artwork © Al Held Foundation, Inc. / ARS, NY

Image description

A photograph of two men in conversation between two large colorful geometric abstract paintings hanging on a worn white wall. The man on the left is light skinned with short dark hair; he wears blue jeans and pale yellow shirt and holds paint swatches in his right hand. On the right, a light skinned middle aged man wearing paint-stained jean shorts and a white t-shirt points at the wall with his right hand. Various bottles of paint are lined up on the concrete floor against the bottom of the wall in between the men and paintings.