New Paths to the Future

Experiments in Art and Technology

In the summer of 1966, I waded into a marsh in Long Island holding a video camera to film Steve Paxton’s feet as he walked through the mud. The image was relayed live to screens lining a path from the road to the audience area for Robert Whitman’s performance Two Holes of Water, the first iteration of a work that he would reconfigure and stage in New York two months later as part of the landmark 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering. On October 5th, we moved from the marsh to the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue alongside a large group of artists and engineers. With a mere eight days to turn the empty drill hall of the armory into a working performance space, we set to work installing lights and speakers, building a control room, assembling equipment, and holding rehearsals as close to a given schedule as possible. In addition to my main task of finding film material for Whitman’s work—I remember being very proud of finding a documentary on Emperor penguins—I, like so many other friends and colleagues of the artists, got swept into the whirlwind of activities of preparing for 9 Evenings. I particularly recall sitting with Simone Forti and John Cage at a makeshift table, soldering connectors we called “tiny plugs” onto the miles of audio cables needed for David Tudor to move the sounds from speaker to speaker around the Armory in his work, Bandoneon!.

As it often happens, when you are in the middle of a revolution you are not aware of all the events leading up to it, or the actions shaping it. I was not aware of the discussions that were going on that fall that led Whitman, Fred Waldhauer, Robert Rauschenberg, and Billy Klüver, to found a new organization, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). The experiences of the four founders that brought about the new organization were varied but aligned. Robert Rauschenberg, as early as 1959 embedded a radio behind the canvas in his Combine painting Broadcast, with knobs for the visitor to turn sticking through; and in Pantomime (1961) had mounted two working fans facing each on the to the sides of a painting, the power cords disappearing behind the painting. Robert Whitman had included film in his theater pieces as early as 1960: beginning with Super 8 in The American Moon, and then overlapping projection of 16 mm film in Prune Flat (1965), and was developing an interest in advanced optics. Engineer Fred Waldhauer, who was working on advanced switching systems at Bell Laboratories, had a passion for jazz and contemporary music and worked with jazz musician Leroy Parkins to incorporate electronic music into his performances. But it was Billy Klüver, a research engineer at Bell Laboratories, who had most directly tapped into the growing interest among visual artists, dancers, and composers in using elements offered by rapid technological developments.

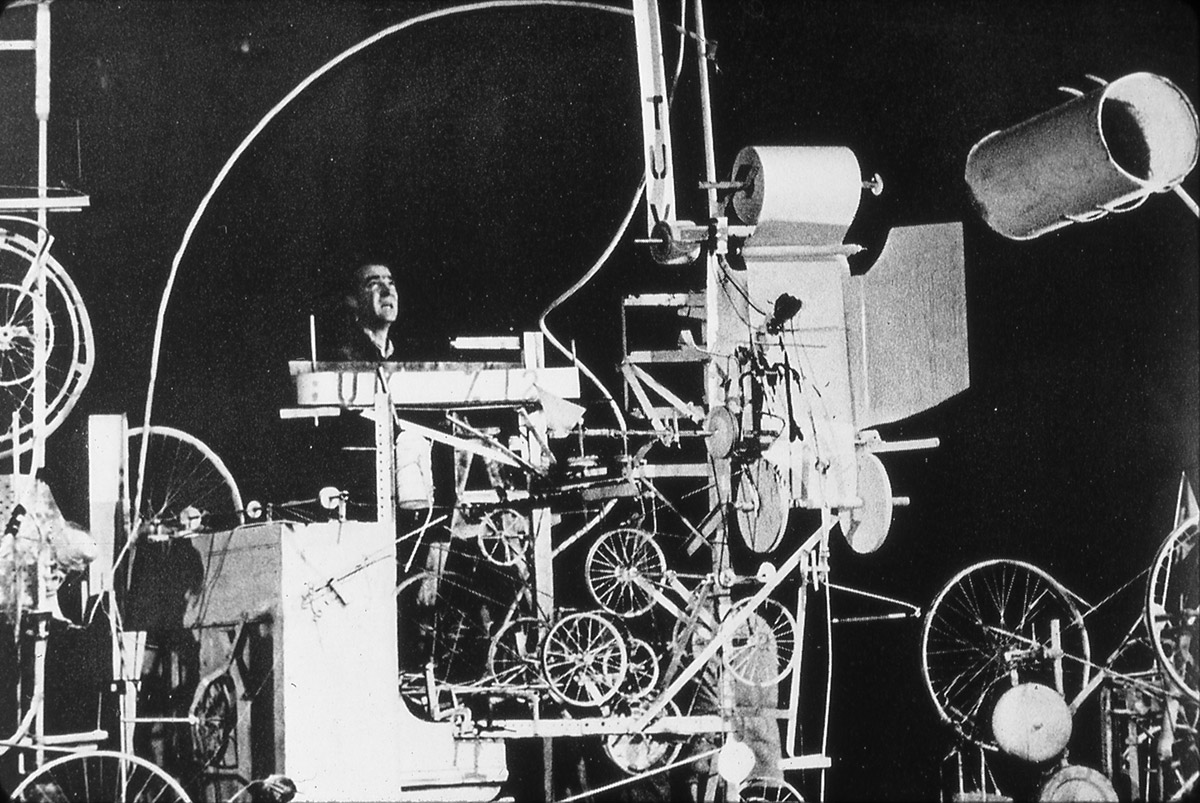

Jean Tinguely stands behind his self-destroying drawing machine, designed and constructed in collaboration with engineers Billy Klüver and Harold Hodges, at the beginning of its operation. The event, titled Homage to New York, took place March 17, 1960, in the sculpture garden at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Photo: David Gahr, courtesy the Estate of David Gahr.

Inspired by his work with Jean Tinguely on Homage to New York (1960)—a 27-minute performance wherein one of Tinguely’s mechanical drawing machines destroyed itself during the process of making drawings—Klüver began to ask the artists he met in New York if there was some idea they had that could be realized using some technology they did not have. The first to respond was Rauschenberg, whom Klüver had met during the preparations for Homage to New York, when he appeared with what he called “a mascot” for the machine: a small explosive box, Money Thrower (1960). Klüver remembered that Rauschenberg “asked me to collaborate on what he described as an interactive environment” where physical elements—light, sound, smells, temperature, etc.—of a room would change as a person walked through it. The technology of the time was not advanced enough to realize this idea, so after many discussions Rauschenberg proposed a sculptural sound environment where the sounds from five AM radios emanate from five sculptures. The viewer would be able to turn knobs on the radios in one sculpture to vary the volume and the rate of scanning through the frequency band of each radio, and the sound would be transmitted to speakers in the other four pieces. Rauschenberg wanted no wires between the control unit and the radios so the pieces could be moved freely in relation to each other. It took until 1965 for available wireless technology to catch up with them, enabling Klüver and his assistant Harold Hodges to design a system that would work without noisy interference.

As Klüver worked with more artists, including Jasper Johns, Yvonne Rainer, John Cage, and Andy Warhol, he enlarged his initial idea of the engineer providing new material to the artist and recognized the value of the one-to-one collaboration. Working directly with an engineer, the artist gained direct access to new technical ideas and material for his work, but there was benefit for the engineer as well. Klüver felt that the collaboration with artists could solve one of his great concerns: the isolation of engineers and scientists from the larger society in which they were operating. His colleagues at Bell Labs were brilliant researchers and engineers, but many of them were unconcerned with the social implications of their work and their role in contributing to the development of social forms. Klüver thought that working with and being exposed to the thinking and milieu of the artist could change the way engineers and scientists saw their work, and accept more fully their role in shaping the technology in ways more beneficial for the individual and for society.

Klüver looked for opportunities to enlarge the scope and impact of artist-engineer collaborations. The first came in late 1965 when the Fylkingen Music Society in Stockholm asked Klüver to organize an American component for a Festival of Art and Technology. Enlisting Rauschenberg’s help, they invited artist friends—composers John Cage, and David Tudor, choreographers Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, and Yvonne Rainer; and visual artists who made performance pieces: Alex Hay, Öyvind Fahlström, and Robert Whitman—to meet with a group of engineers from Bell Telephone Laboratories at Murray Hill, New Jersey, to develop technical equipment that would be used as an integral part of the artists’ music, dance, and theater performances. Over the next ten months, more than thirty engineers worked in one-to-one collaboration with individual artists, or made up a group that designed equipment and systems to be used by the artists to control sound and lights and movement of objects in all of their performances.

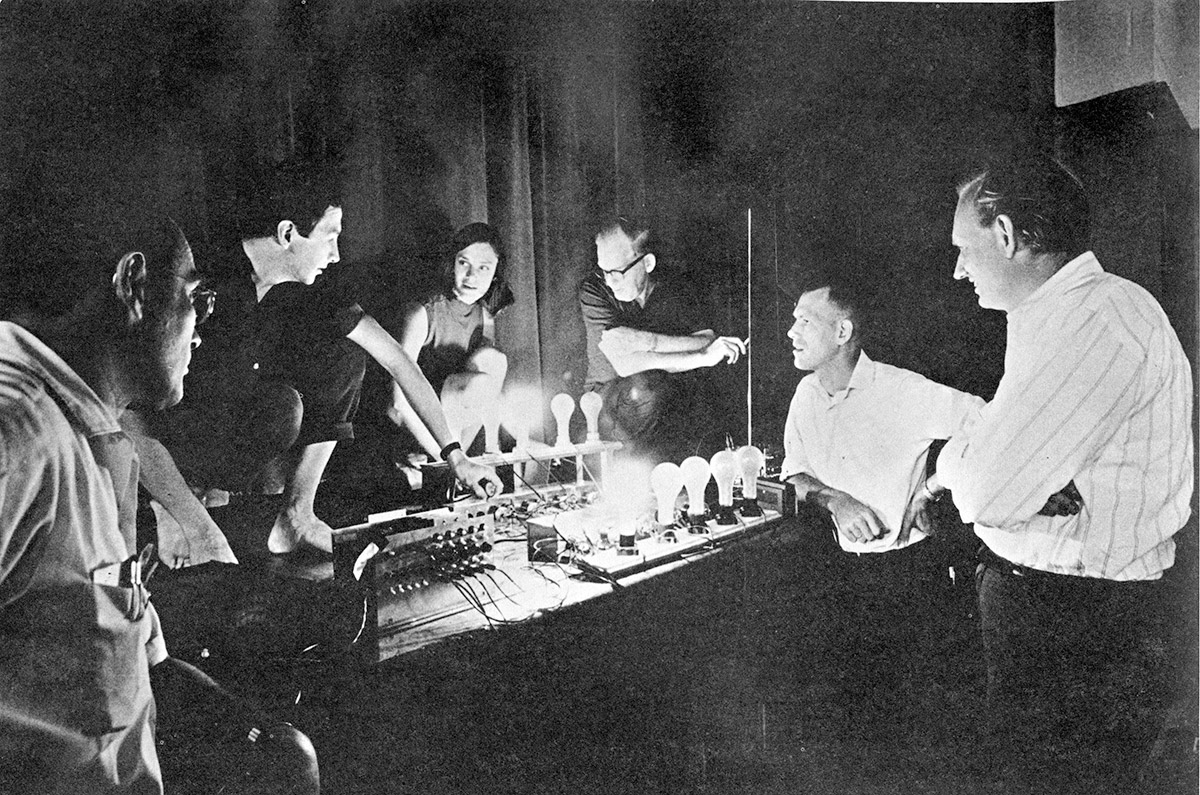

Artists and engineers demonstrating the TEEM light and sound control system at a technical rehearsal for the performances at 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering.

From Left: Herb Schneider, Robert Rauschenberg, Lucinda Childs, Roby Robinson, Per Biorn, and Billy Klüver. Photo: Franny Breer

The resulting Theatrical Electronic Environmental Modular (TEEM) System was the first of its kind. No such system existed in the theater, and the engineers were proud of the small portable amplifiers, pre-amplifiers, encoders, decoders, and FM transmitters they designed and built that could, for example, transmit the sound of the ball hitting a tennis racket in Rauschenberg’s Open Score, to loudspeakers, making loud “bongs” throughout the Armory and turning off one light with each “bong” as the game progressed into darkness. The system was employed in very different ways in Deborah Hays’ piece Solo to guide remote- controlled platforms around the Armory floor; or for David Tudor to move the sounds from his bandoneon from speaker to speaker around the Armory.

The American group did not go to Stockholm, but decided to stage their performances, titled 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering at the 69th Regiment Armory from October 13 to 23. Many artists and friends in the art community were involved. The event was widely publicized and generated a lot of interest; more than 10,000 people attended the performances over the nine evenings.

Robert Rauschenberg, Open Score. 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, October 1966. Overview of the tennis game, played by Frank Stella and Mimi Kanarek. Each time the ball was hit, a loud “bong” was heard throughout the Armory and a light went out. The game continued until complete darkness. Photo: Adelaide de Menil.

In this atmosphere of innovation and excitement, Klüver, Waldhauer, Rauschenberg, and Whitman decided that artist-engineer collaborations like the ones that had developed during their work on the 9 Evenings should be available to other artists. The energy and enthusiasm generated by the event was directed toward founding E.A.T, and the response from the art community was immediate. More than 300 artists showed up at the first New York meeting in November 1966, and more than 70 people had immediate technical questions or projects they needed help with. Membership in E.A.T. was open to all artists and engineers, and an office was set up in a loft at 9 East 16th Street in New York.

I left New York in November of 1966 to participate in a television series for CBC on the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but caught up with E.A.T. the next summer, while working for Christophe de Menil on a second series of Midsummer performances on Long Island. I joined the group at the beach where Klüver, Rauschenberg, Whitman and others were discussing next steps. Soon after that, Klüver and Waldhauer asked me to join the staff of E.A.T. as editor of the newsletter. I began to work with Klüver on this newsletter, articulating the ideas behind the organization, the ideas that “hooked” me and led me to take part in its activities and projects over the next decades.

As Klüver and Rauschenberg wrote in an early newsletter:

The collaboration between artists and engineers should produce far more than merely adding technology to art. …Engineers who have become involved with artist’s projects have perceived how the artist’s insight can influence his directions and give human scale to his work. The artist in turn desires to create within the technological world in order to satisfy the traditional involvement of the artist with the relevant forces shaping society… The collaboration of artist and engineer emerges as a revolutionary contemporary sociological process. …E.A.T. is founded on the strong belief that an industrially sponsored, effective working relationship between artists and engineers will lead to new possibilities which will benefit society as a whole.1

While the founders were working to articulate the ideas behind the organization, they were also active on the ground to make it happen in the real world. Klüver and Waldhauer began to develop services for artists which included loans of equipment; a lecture series by engineers and scientists for artists on technical subjects like lasers and holography; computer generated sound and images; television; plastics and other new materials; and, most important, launching a system for responding to artists’ requests by matching them with engineers or scientists to provide technical information, short term assistance, or longer collaborations. By 1969, there were over 2,000 artist members and 2,000 engineer members willing to work with artists from all over the United States and abroad.

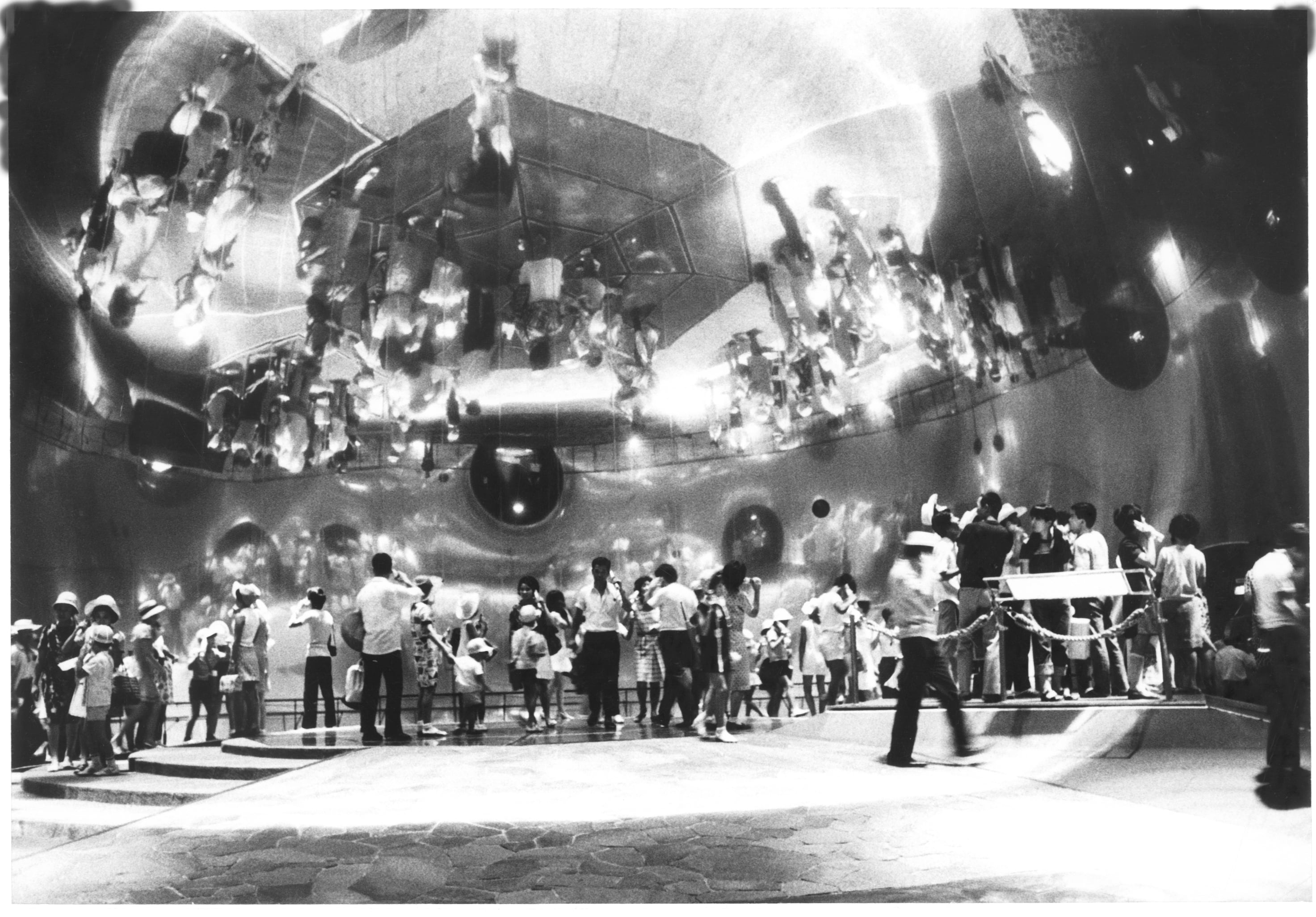

Mirror Dome room inside Pepsi Pavilion. The real image of the visitors on the floor appears upside down over their heads. Photo Shunk-Kender.

This commitment to the artist as an agent of social change became more pronounced as E.A.T. began to organize and administer projects that would expand the opportunities for artists to work with collaborators in different roles and in different parts of the world. Whitman and Klüver continued to generate projects in which the artists and engineers participated in new areas of technological and social development, projects whose outcome was not a formal work of art. The first and largest of these was the project to design, build, and program the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan. Initiated by four core artists—Robert Breer, Forrest Myers, David Tudor and Robert Whitman—more than twenty artists and fifty engineers and scientists contributed to the design of the Pavilion.

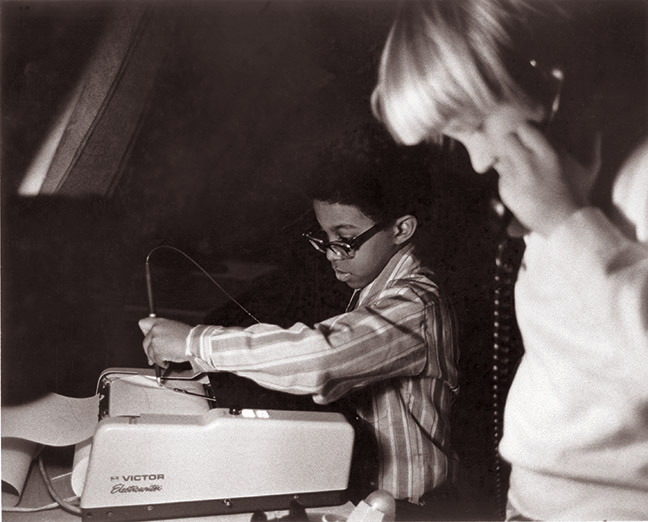

The other interdisciplinary projects developed by Klüver, Whitman, and the E.A.T. staff in the early 1970s were broadly called Projects Outside Art, and included the Anand Project, which developed instructional software for satellite-based education for women in rural villages in India who raise and tend milk-producing buffalo; City Agriculture, which developed plans for automated nutrient-feeding rooftop gardening units that would allow residents to grow their own vegetables; Children and Communication, which established two centers linked with telephone equipment to connect children aged six to thirteen in different neighborhoods in New York City; and Telex: Q&A, a project involving New York, Stockholm, Ahmedabad, India, and Tokyo that allowed people in each country to ask and answer questions about the future.

The most active years of E.A.T. were from 1966 to 1973. The Technical Services Program continued to match artists with engineers and scientist for individual collaborations. But as the 1970s progressed, the structures and institutions that dominated education, international development, and communication systems were not ready to accept the artist as a participant. Funds for specific projects were not forthcoming, which in turn led to cutbacks in operations. However, as Klüver had predicted in an early newsletter, “As E.A.T. becomes successful, many of its functions can be transferred to industry, to professional engineering societies, to universities.” This transfer gathered momentum in the 1990s and continues today. Art schools and universities, as well as engineering colleges and technical schools now offer courses in “art and technology.” Many are establishing programs to encourage collaborations across disciplines and across departments. Industries and research laboratories now encourage artist-in-residence programs, placing working artists within the industrial environment to work on projects of their choice.

Looking back at E.A.T.’s legacy, it is clear that the ideas of incorporating non-art elements into works of art and of artist-engineer collaboration took root and have successfully become part of the culture. The structural impediments to artist access to technology and industry so prevalent in the 1960s have disappeared. With the development of digital technology and digital tools, the individual has been empowered; access to new technologies and an increasing array of technical tools make it much easier for the artist to make his/her works. The ideas embodied in E.A.T.’s Projects Outside Art can be detected in artists’ increasing interest in launching ventures that address problems and shortcomings in society and search for solutions to issues of the environment, free speech, urban planning, and human development.

For those of us who were young adults in the 1960s, it was a time of ferment and conflict, but also a time of great optimism, belief in the power of the individual to play an active part in making the world a better place, bonding with others to make changes in society: to end the war, to expand civil rights and end the most egregious manifestations of segregation. Certainly the art world was full of this energy and optimism, with artists looking at and taking inspiration from the world around them, seeking to be engaged in it. The promise of the artist as a catalyst for change had less to do with specific artists’ projects than with the power of collaboration to find new paths to the future.

Fifty years later, one can see that E.A.T. was as much an idea, a belief system, as an organization; but it was an organization very much of its time.2 The development of digital technologies (and, of course, the Internet) has brought greater access to information and communication, and given the artist a global platform. But it also holds the possibility of more complete control and surveillance over individuals’ lives and even greater concentrations of wealth and control that threaten individual expression. So for the more idealistic goals and visions that inspired the founders of E.A.T., one can only say that Utopia always has a continuously receding shore. The dilemma facing artists, engineers, and scientists today is to preserve the freedom, autonomy, and creativity of the individual in the face of consolidation of corporate power and perversion of political power. The history of E.A.T. holds the promise that by working together, by exploring and using the tools provided by technology, artists, engineers, and scientists can effect change. An essential element in these collaborations for the future is the artist. As Waldhauer once said, “In building the future, we are all amateurs, but the artist might just be the best amateur.”

1 E.A.T. News, Volume 1, No 2, June 1, 1967, p 1.

2 Today, E.A.T. is largely involved with documenting its history, producing a series of documentary films on the performances at 9 Evenings, creating a website to make the history and ideas of the organization more readily available, and assisting curators planning exhibitions on the history and activities of E.A.T. The archive of E.A.T. activities from 1966-1993 has been placed at the Getty Institute for Study of Art History and the Humanities in Los Angeles; the archive of film and other material on 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering has been placed at the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science and Technology in Montreal, Canada.

Main image

Billy Klüver and Robert Rauschenberg work on Oracle in Rauschenberg’s loft on Broadway in 1965. Photo: Larry Morris/New York Times