Intergenerational Dialogues at the Dedalus Foundation

On the occasion of the Fall 2016 issue of VoCA Journal the Foundation’s President and CEO, Jack Flam, sat down with Programs Director Katy Rogers to discuss the organization’s mission and how it is enacted through a dynamic roster of evolving programs.

Katy Rogers: Jack, you were a close friend of Robert Motherwell’s and have been president of the Dedalus Foundation since 2002. Can you tell us something about how and why Robert Motherwell created it?

Jack Flam: Motherwell began the foundation in 1981, as the Motherwell Foundation, but changed its name shortly before he died in 1991, in order to emphasize that the foundation would have a purpose that went beyond looking after his own artistic legacy. Motherwell was a great admirer of James Joyce and the new name referred to Stephen Dedalus, Joyce’s alter-ego, an archetypal artist (who was himself meant to recall the great fabricator Daedalus of Greek mythology). Renaming the foundation in this way was an indication of the broad scope Motherwell envisioned for the foundation’s activities.

Motherwell was not only a great artist but also one of the major cultural figures of his time. He wanted his foundation to be dedicated not only to his work but informing the public about modern art and modernism conceived in the broadest possible way. Motherwell had a wide range of interests, which extended beyond the visual arts per se, to modernist literature, music, and dance, and we have kept this diversity in mind as we developed our programs. In particular, Motherwell had a deep interest in education on all levels. He was interested in developing the creativity of children as well as that of adults, and for many years he taught at Hunter College. This is a legacy that the Dedalus Foundation has continued over the years, and to which we have given a particular emphasis, especially under your leadership as Programs Director in recent years. Can you say something about how our programs have developed?

Rogers: Over the last ten years the most important programs at the Dedalus Foundation have been the publication of the catalogue raisonné of Motherwell’s paintings and collages in 2012 and, more recently, the education programs which continue Motherwell’s legacy in a different way. The catalogue raisonné involved eleven years of research into how Motherwell created his works, how they were exhibited and received by the public, and about technical issues that could aid in their conservation. We worked closely with James Martin of Orion Analytical on a study of Motherwell’s early paints and supports, which helped us to understand the methods and material choices of the artist during crucial points in his career. Since the publication of the catalogue raisonné, the foundation has developed a wide spectrum of programs in a number of areas. In addition to our programs in education, we have given special emphasis to conservation, various aspects of archival studies, research and publication, and of course to the continued stewardship of Motherwell’s work and legacy. For the past three years we have had a space at Industry City, in the Sunset Park area of Brooklyn, where we offer art education classes for people of all ages. These classes include family art making, portfolio classes for middle and high school students, and also work with adults in ESOL (English as a Second or Other Language) and high school equivalency programs. In addition to that, we support advanced scholarly and creative work in a number of fields. For many years we’ve supported fellowships at other institutions, such as our Fellow in the conservation of modern and contemporary art at the Institute of Fine Arts Conservation Center, and also the Dedalus Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art Archives.

Flam: All of these programs have a good deal of energy behind them. But one might ask whether they are guided by underlying ideas or concepts, other than just the abstract idea of doing good. And if so, how do those ideas relate to Motherwell’s own ideas about education, for example?

Rogers: The overriding idea or unifying concept behind all of our programs is to help change people’s lives for the better, through art. Motherwell left us a very broad mission statement about furthering the understanding of modern art and modernism. We have taken that and looked at examples from his own life: his teaching at Hunter College, where he was a pioneer in American art education by emphasizing self-realization over technique; his numerous lectures and essays; his interest in children’s art; his editing of the Documents of Modern Art Series; and his work on the Subjects of the Artist school back in the late 1940s, with his colleagues Mark Rothko, William Baziotes, David Hare, and Barnett Newman. In providing opportunities for art making we are opening up the potential for dialogue between people and the world around them, for exploring their emotions and their potential for connecting with a larger community—for exploring the nature of reality. In his essays, Motherwell talks about the way the modern artist’s principal concern is “to express the felt nature of reality,” and how modernist art is a “gallant attempt at a more adequate and accurate view of things now.” Our education programs have a similar goal—to help people better understand themselves and the world around them, through art.

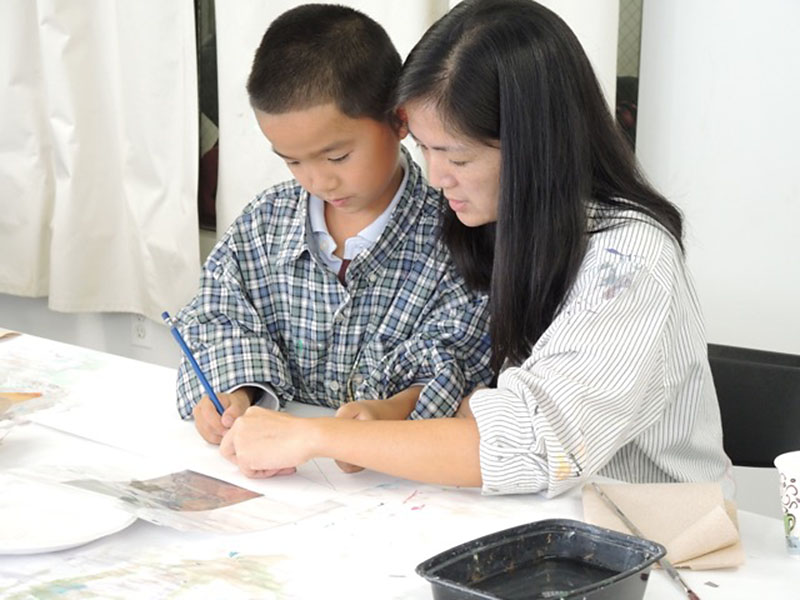

Flam: One of the things that impresses me about the way in which you’ve been directing our educational programs is how self-realization is seen not only in relation to individuals realizing aspects of themselves, but also the ways in which that self-realization performs a kind of a social function. Curiously enough, self-realization seems to provide a kind of social good in that the more people realize their own inner potential, the more they seem open to becoming constructive members of society. Something I find very inspiring about the events you and your team have developed in Industry City, where we’ve had a lot of people taking our classes, is the strong sense of community spirit.

Rogers: We’ve tried to create a space where all are welcome and there is a sense of support not only for the individuals but also for the surrounding community. For example, we’ve focused on connecting with community-based organizations in Sunset Park, such as Turning Point Brooklyn and the Center for Family Life. We work with the staffs of these organizations to amplify what they’re already working on, and also expand their arts programming. And they, of course, expand our horizons, and encourage us to think of ourselves as part of a larger network and not as working alone or apart from society.

Flam: One very important thing about how you’ve structured our programs has to do with the broad spectrum of people that it addresses. That is, not only is there a broad age range, but there’s a broad range of kinds of services that are provided to different sub-communities within the larger community, as with the portfolio programs.

Rogers: The portfolio preparation program came out of a need expressed by a local middle school teacher who had a number of talented young students interested in applying to the competitive arts high schools in New York City. We started three summers ago with a middle school portfolio program aimed at local students. And each year we’ve been able to further fine-tune the program so it provides maximum benefit to the students. And then we found that there was also great interest for us to provide a similar program at the high school level, teaching students to create portfolios that would help them to get into colleges with first-rate arts programs. All of the classes are taught by professional artists who guide students in creating a high caliber portfolio and also help demystify the application process. Another very gratifying aspect of this program is that it offers a means of support for practicing contemporary artists through teaching positions. This again reflects some of Motherwell’s long-standing interests, by creating an inter-generational dialogue that focuses on the artist as educator.

Flam: The foundation also gives a number of fellowships to people who specialize in archives and conservation, as well as to young artists, in our MFA Fellowship program, and both to Ph.D candidates and senior scholars who are writing about modern art and modernism. Can you say something about the ways in which various holders of fellowships interact with each other, and with the foundation’s activities?

Rogers: These fellowship and scholarship programs have been a core aspect of our activities for around twenty years or so. But recently we’ve come to realize that we had this network of very interesting and lively scholars and artists and college students, and we became interested in giving them opportunities to present their research under the auspices of the foundation, in a context that would serve as a fertile ground for discussion. We wanted to create a forum in which artists and arts professionals and students could mingle and discuss contemporary issues related to modernism, modern art, and modern society. By working with our fellowship network we have been able to generate programming with our conservation fellows at the Institute of Fine Arts Conservation Center. Those young conservators have gone on to have internships and fellowships at other institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and we were interested in giving them a platform to talk about the work they had done during and after their fellowship periods. Recently, we have had sessions moderated by our former conservation fellows on Robert Gober’s work, on Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, and on the conservation of Donald Judd’s sculpture. These panels created the space for wonderful conversations between conservators, artists, art historians, curators, and interested members of the general public. That creates a rare opportunity, as those fields tend to be a bit isolated from each other. But we’ve been able to break down some of those barriers, while giving opportunities to our current and former fellows—and also providing extremely interesting and informative evenings for the people who attend them.

We’ve been recording all those programs, so we can disseminate the results more broadly via links on our website.

2012-2013 Dedalus Fellow in Modern and Contemporary Conservation, Amy Hughes, using a hand held vacuum and brush to clean the surface of a 1964 painting on paper by abstract expressionist Lester Johnson.

Flam: Could you say something about the oral history program that the foundation has been involved with, not only in relation to Robert Motherwell but also in the broader context of oral history as a means of creating and disseminating information?

Rogers: We have found, much as VoCA has found, that having a recorded conversation about a subject can be a key component of both research and legacy work. So for Robert Motherwell, we have conducted interviews with people who were close to him during his life. That program was originally part of the catalogue raisonné project, but is ongoing, and we hope to develop it further in the future. In the fall of 2013, we did a program with VoCA, around the exhibition that marked the first anniversary of Hurricane Sandy, which we co-produced in Industry City. In that oral history project, artists were interviewed by conservators, and there was a good deal of discussion of how one might prepare for a major disaster such as Hurricane Sandy, and how one could try to recover from such a traumatic event–both in a personal sense, and also in an artistic sense. We hope to make these videos more widely available in the future. During the past several years, we’ve also supported conferences about oral history, notably at the Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with Columbia University’s oral history program.

Flam: What about the high school Scholarship Program, which is one of the foundation’s longest running programs, and how that has also evolved over the past few years?

Rogers: Our high school scholarship program is operated in conjunction with the New York City Department of Education. It is a two-pronged program. One part is a portfolio program, a competition where graduating seniors can submit portfolios of their artwork to compete for a scholarship of $2,000; we give seven of those every year. We do not stipulate how the money be used; rather, we give them the freedom of choice, understanding that being an artist isn’t just about tuition or buying art materials.

The other component of our high school program that is unique to the Dedalus Foundation is an art history research program, in which we have some fifty participants each year, of whom five students with winning projects receive scholarship money. There are some high schools in New York that have art history programs, but it’s fairly rare for a teenager to be able to learn about art historical research on a deep level. So we work very closely with their teachers to supply both the educators and the students with resources over the course of the year that allow them to explore art historical research. Each student writes about a specific work or topic, and at the end of the school year some give brief lectures that summarize their research. The lectures are given the same afternoon that a show of the fine arts winners opens in our gallery space at Industry City, and it is great to have all the students, teachers, and parents come together for that dual event.

Among other things, these programs introduce the students to the multitude of careers in the arts: conservation, archives, collections, curation, arts education, and so on. At the end-of-year event, you see the light begin to dawn on both parents and students that it just might be possible to actually have a career in the arts. Opening up these sorts of possibilities is what is at the root of all of the Dedalus Foundation’s programs.

Further Reading

Arts Education Programs at Dedalus: http://dedalusfoundation.org/arts-education-program#/en/Featured

Catalogue Raisonné: http://dedalusfoundation.org/catalogue_raisonne/paintings_collages

Center for Family Life: http://sco.org/programs/center-for-family-life/about/

Motherwell Bibliography: http://dedalusfoundation.org/motherwell/bibliography

Motherwell Exhibition History: http://dedalusfoundation.org/motherwell/historical_exhibitions

Motherwell Writings: Motherwell, Robert. The Writings of Robert Motherwell. Edited by Dore Ashton with Joan Banach. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Turning Point Brooklyn: http://www.tpbk.org/

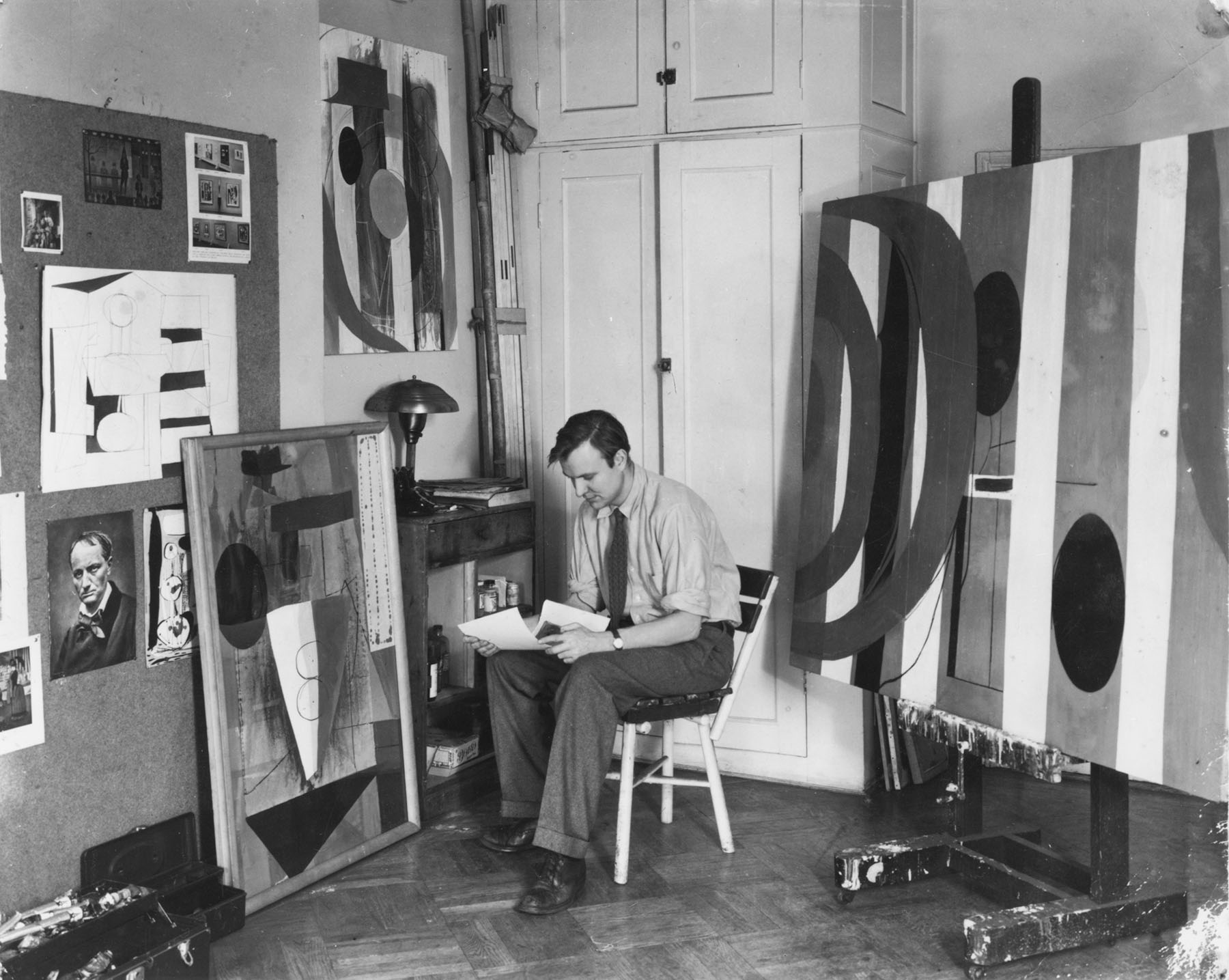

main image:

Motherwell in his studio with Wall Painting with Stripes in progress and Collage in Beige and Black, ca. 1945

Photo by Peter A. Juley & Son

Courtesy of the Dedalus Foundation Archives