Creating the Artist Archives Initiative

at New York University

The David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base is a one-of-a-kind digital information resource created by the Artist Archives Initiative at NYU to aid curators, conservators, and others who are researching the work of David Wojnarowicz. The project was launched with a Symposium at Fales Library & Special Collections on Friday, April 21, 2017. In preparation for this Symposium, project directors Glenn Wharton, Marvin J. Taylor, and Deena Engel sat down to have a conversation about where the Initiative began, and how it has evolved in the two years since then.

Glenn Wharton: It seems like yesterday when we first had the idea of creating the Artist Archives Initiative at NYU. I remember an early conversation when we were searching for an artist that we could work with to create a digital resource for curators, conservators, and other researchers. Marvin said, “We have to choose David Wojnarowicz!” My reply was, “But he’s dead!” I had envisioned working with a living artist to shape an information resource about their work. Then when Marvin reminded me of the posthumous migration of Wojnarowicz’s works, and the complications involved with being true to an activist downtown artist who is increasingly shown in white cube gallery spaces, I realized that Marvin was right. I also saw that we could work with graduate student researchers to mine his personal papers at the Fales Library and Special Collections. Before we go into the details of the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base, Marvin, could you say a little about your background and how you came to create the Downtown Collection of artist papers at Fales?

Marvin J. Taylor: Sure. I was interested in experimental art, and I knew about the downtown art scene of the ‘70s and ‘80s and into the ‘90s. I mentioned to the dean that I would like to collect this material. It seemed to fit with NYU and it certainly fits with our neighborhood. He said, “Go see what you can find.” So the Downtown Collection was founded in 1994, and today it accounts for some eleven thousand linear feet of archival material, about all of the arts downtown. It includes materials on installation art, music, performance, dance, and theater. One of the most important collections is the David Wojnarowicz papers. The fact that he worked in multiple media and didn’t specialize is indicative of what other downtown artists did and that made him an especially interesting choice for our first project.

Wharton: Deena, could you tell us about your background and role in this project?

Deena Engel: I would be happy to. I am on faculty at the Department of Computer Science here at NYU. I run the undergraduate minor’s programs, offering computer science and web development courses. I’m also the director of a new graduate program in Digital Humanities. In addition to the educational work that I do, my research is on the conservation of software-based art, working with conservators and colleagues at the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum. I’m lucky to also have colleagues at other museums, such as SFMOMA and Tate. It has been exciting for me to participate in this project, steering the technical research to develop the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base and get it ready for the April 21 launch.

Wharton: Deena, I remember when you and I worked together at MoMA with your computer science students to perform technical risk assessments of software-based works in the collection. The work I did at MoMA, interviewing artists and building documentation for the museum, led me to this project after I moved over to the university. Now that I can be proactive in my research projects, building artist-based information resources for curators, conservators, and other researchers was the first thing I wanted to do. I was fortunate that the two of you saw value in this, since you each bring different areas of expertise. I’m just curious Marvin, why did you think David Wojnarowicz was a good artist for us to start with?

Taylor: I think Wojnarowicz was the ideal artist for this because of the way he worked and the fact that he collaborated with so many people. Many of the people he worked with are still around, so we could interview them about his working methods and concerns for displaying his work. His art calls on us to think very differently about what a work is, together with the people, texts, and places associated with it. Developing this resource was the obvious next step for Fales to complement the finding aid that we developed for his personal papers. Many researchers want to know how to exhibit or conserve his work, and the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base will provide them with this information. It will get the researcher deep into the work and the related archival materials.

Engel: I agree with Marvin. Also, it has been a true Digital Humanities project in that we combined technical research on the information resource by students from computer science with humanities research by a broad range of students from programs at the university, including Archives, Art Conservation, Art History, English, Moving Image Archiving Preservation, Media & Communications, Museum Studies, and Oral History. One of the computer science students stopped by my office the other day specifically to tell me what a seminal project this has been in her education, and how much she believes this will impact her career in such positive ways.

Graduate student Diana Kamin interviewing artist Sur Rodney Sur for the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base. Photo: Glenn Wharton.

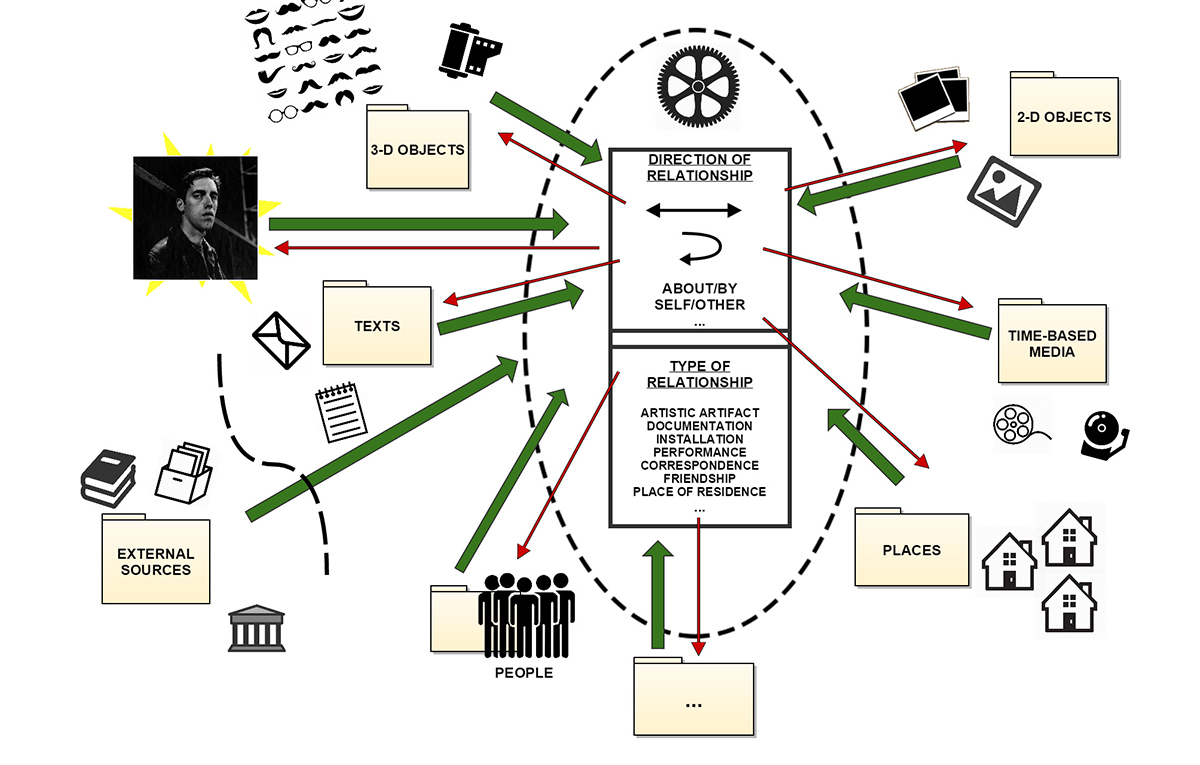

Taylor: One of the moments during our project that was most engaging to me happened during the first summer, when our graduate student researchers were sketching out the relationships between Wojnarowicz’s works, his collaborators, places associated with the works, and the texts in the papers. They realized that we had to create an information resource that focuses on the works, not the artist himself. Yet we couldn’t just describe works, we had to develop a rich system that allows users to explore relationships. I remember in one of our advisory committee meetings when we rolled this out Rob Slifkin (Art Historian, Institute of Fine Arts) was sitting next to me. He said, “Oh, now I get it.” He saw that this was a very new model for looking at art, and Wojnarowicz led us to that.

Schematic diagram illustrating complex relationships between Wojnarowicz, other people, artworks, places, and research sources. Image: Francisco Chaparro.

Wharton: This realization was indeed a game changer for us. For me, the difficulty of working with a museum collections management system is that they are structured hierarchically and it is always difficult to decide where to put information when it doesn’t quite fit within fields that were set up for traditional object-based art. For instance, when I first arrived at MoMA, there was no field for duration. We would enter “twenty minutes” in the dimensions field. We also had difficulties in identifying artwork genres. We would call a work a performance even though there were exhibition materials associated with it, knowing that these decisions were going to cause a lot of headaches in the future. In designing our information resource, I was aware that the decisions we made about how to classify artworks, people, places, and texts, would shape the researcher’s knowledge. The web of relationships was complicated. Fortunately Deena and her computer science students were able to investigate emerging technologies that could address these concerns.

Engel: When the project got started in the summer of 2015, I realized this was really a fascinating database problem, and I was delighted to be involved. I will never forget the morning that the students were grappling with the concept of how to structure knowledge about the works of art. I think that a teacher’s role is to stand back and support, not to direct. It was wonderful to watch the conversation evolve. Light bulbs went on when they realized that it is about tracking relationships among the objects, the collaborators, the places, and the texts. That is when it became a fascinating database problem.

Wharton: Could you talk a little bit about the hierarchical nature of standard databases and the horizontal nature of what we tried to accomplish?

Engel: The structure of a traditional database is fairly rigid in the sense that we might have a list of artists and we might have a list of works, each of which is defined in fairly predictable ways. If we were looking at a collection of seventeenth-century European paintings, we probably would be very successful at organizing the data so we could find all of the paintings by Rembrandt, for example. With Wojnarowicz, we needed some kind of a hierarchy for managing the data, for instance to distinguish two-dimensional and three-dimensional works, but within two-dimensional works there are multiple subdivisions. Some include paint, text, or photographs. Some include all three. We needed to catalogue the works in multiple ways, and we wanted researchers to find them when searching for paintings, text-based works, or photographs.

Wharton: I remember we had an ah-ha moment when we realized in our early wire-frames that the arrows between people, objects, texts, and places went in all directions. A person could collaborate with Wojnarowicz on a work of art, appear in one of his films or performances, or be a gallerist or installer, or all of the above. These multiple relationships complicated our early efforts to classify people in our resource.

Engel: We needed to use controlled vocabularies as malleable tools without sacrificing the ability to do deep searches into the data. We needed to allow all of these people, texts, and works of art to be readily discoverable.

Taylor: The Magic Box is good example of a complicated archival artifact. It’s questionable whether it’s a work of art or not. We know that Wojnarowicz didn’t display it and that it was very personal. It’s an orange crate that contains about eighty objects of all different kinds of media, everything from ants in amber, to money, to a monkey sculpture painted blue. The objects represent a symbolic set that Wojnarowicz worked with in all of his art, including in writing, photography, painting, installations, and performance. It is basically a set of physical metaphors, many of which appear in his films and photographs. So they are associated with various works but they are not artworks themselves. How do we classify them? When I first looked at it, I thought, “Oh, there’s something about this that takes us deep into Wojnarowicz’s mind.” And we know very little about it because he didn’t tell people. Even his partner Tom Rauffenbart said, “Yeah, David would take it out and play with it once in a while, but he really never talked to me about it.”

David Wojnarowicz, Magic Box, n.d.

Mixed media box, 20 x 28 x 43 cm

From the David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, New York

Taylor: Another group of objects that are hard to classify are the props that Wojnarowicz used in his performances, films, photographs, and installations. An example is the wolf’s head in our collection. It has been exhibited independently but it is associated with various works. He used it in Rosa von Praunheim’s film Silence = Death, for instance. As a visualization of HIV, it has a complicated set of references. He constructed it in papier-mâché and it is covered with newspaper articles relevant to the AIDS crisis and the denial of federal funding for people infected with HIV. We wanted to get all of these associations in the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base.

David Wojnarowicz, Wolf’s head

Papier-mâché mask, 26 x 19 x 14 in.

Fales Library and Special Collections

Wharton: Deena, could you tell us how you and your team took these challenges to your own research in identifying and developing an information management system for our resource?

Engel: My students and I began by examining the data being compiled by the humanities students on Google sheets. Over several months we researched what was happening in the field by surveying the literature and looking at a number of data management systems for different collections and different artists from a technical perspective to get an overview of common open-source technologies that we might consider. For example, we considered using Omeka, an open-source cataloging system; and we considered Drupal, an open source framework for building online database management systems. In the end we settled on using a wiki platform, MediaWiki, as a way to support both a hierarchical menu and to provide a lateral view using the wiki’s “categories” structure. MediaWiki is the same software used for Wikipedia so we knew there’d be a fairly shallow learning curve for the users. Once we started working with MediaWiki, we realized it needed a lot of configuration. We spent months adding data and customizing the wiki, but we did not want to use custom programming on the wiki software, as that would make preservation and sustainability more difficult for future support. One of the reasons why we chose MediaWiki is that we know it will be sustained … Wikipedia isn’t going down. It’s very stable software. We also have the benefit of working with the Systems Group at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences where I teach. They have been very helpful. They gave us server storage and occasional wisdom when we had questions, for instance on making the software run faster.

Wharton: It’s been really exciting working across disciplines to develop the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base. Deena, you brought deep technical knowledge, and Marvin provided us with a rich understanding of the artist. My part was to understand conservation and curatorial questions that future users of the resource will have. As we moved along, more research questions kept coming up. Let’s hope that once it is launched, future students and professional researchers will make further contributions to the resource. Archivist gatekeepers at Fales will oversee future contributions. I look forward to launching it and getting feedback at the symposium on April 21. I hope that readers of VoCA Journal will join us at the symposium, and bring their friends and colleagues! I also can’t wait to start working with a second artist to model our second knowledge base. Hopefully the models we develop will be adapted in the future by museums, galleries, collectors, artist foundations, and individual artists to create their own information resources for exhibition and conservation research.

Further reading

Glenn Wharton, Deena Engel, & Marvin J. Taylor. “The Artist Archives Project – David Wojnarowicz.” Studies in Conservation. London: International Institute for Conservation, 61 (2016): 241-247.

main image:

David Wojnarowicz, Magic Box, n.d.

Mixed media box, 20 x 28 x 43 cm

From the David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, New York