Codifying Fluidity

Refresh Rates in Museums Today

As new art forms emerge, museums catch up. They must keep learning as sites of art production, interpretation, and exchange—and to collect the formerly uncollectible. Jim Coddington has been looking forward on behalf of contemporary art conservation for more than thirty years at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Coddington was an early champion of Matters in Media Art, a multi-phased project established in 2003 to offer guidelines for the care of media art. In 2016, MoMA was awarded significant support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to undertake the Media Conservation Initiative, a four-year endeavor designed to advance and share new strategies in the care and conservation of media collections. Jill Sterrett and Jim Coddington sat down recently to talk about his role as advocate for incorporating these new ways of operating into museums.

Jill Sterrett: What was your “aha” moment with media art? When did you say, “I have really just got to dig in and get to work on how we care for and keep electronic media?”

Jim Coddington: I would say it was in 2003 when Pam and Dick Kramlich’s media consortium—the New Art Trust—convened a workshop of the three partner museums (MoMA, SFMOMA and Tate) to begin to articulate how to collect and preserve electronic artworks. Who knew that out of this meeting would come the Matters in Media Art project that just completed its third phase of guidelines last year? I came into the workshop engaged but left with a heightened sense of urgency about what I was supposed to be doing as chief conservator. In looking back, it was the spirit of partnership and generative collaboration operating at the core of the New Art Trust that was not only the innovation of the Kramlichs’ vision but an essential component of how to tackle the larger issues here.

Sterrett: What happened there?

Coddington: I saw the scope of it all: how quickly artists and designers were adopting new technologies as their mediums, the need to cultivate and educate technological wizards as cultural stewards, how trusted cross-disciplinary collaborations were going to be key to success, and the requirement of wholly new tool sets for the preservation of these works.

Sterrett: That’s a pretty concise recap of things we’ve observed for some time now. How did you get the ball rolling at MoMA? What did advocacy look like?

Coddington: I believe in pilot projects as effective test environments for new ways of operating. But first I sat down with registrars and curators that had attended the meeting to consider where media art preservation would be located within the museum structure. For us, it was an open question and we decided the preservation effort would live in conservation. Over time we drafted a series of projects, each one becoming slightly larger, each one inviting new expert voices to the discussions. We started with—what else?—a collection survey. The survey was the basis for a systematic migration of analog works to digital formats, again starting with a small(ish) sample to determine the scope of what we needed to do. When after a few years we needed to make the case for permanent resources and staff, it did not take a lot of arm-twisting; not only did we have support from multiple departments through the museum but we had a working model in place that had demonstrated its ability to do the work we proposed.

Sterrett: Interesting, since I see iterating, a hallmark of the tech industry, in this method. But I also recognize tried and true conservation practice. It sounds like you built an infrastructure somewhat organically in the absence of established practices coming from the field, the field of art conservation.

Coddington: We benefited terrifically from practices developed by libraries and archives but they had to be adapted for works of art and design. It’s still in process, that’s the truth of it. You have to be alert and respond to what makes a system work in a particular place rather than prescribing some textbook solution. How did things get going at SFMOMA?

Sterrett: We did things in a slightly different order. In 1995, we formed a cross-disciplinary working group—Team Media—because we saw gaps in the way we were keeping complex media installations. We upped our game by leaning on each other and, as a result, a deep culture of collaboration took root. Team Media has been at the center of our ever-expanding program of acquisition, display, and care of electronic media art and design.

There are many roads to the same destination though. Remember when our teams started exploring the graphic icons and designs of early Macintosh computers? I’m talking about the Happy Mac that launched on your Macintosh SE/30 when you turned it on, the bomb that appeared when it crashed, the fish screensaver when it slept? A remarkable group of designers, people like Susan Kare, Jack Eastman, and Patrick Beard gave personality and humor to our personal computers. Computer design operates on so many levels: the box, the underlying operating system, the software and the user experience. Museums are learning how to collect, keep, display, interpret, interact with and share design on all of these levels.

This video shows the program MiniVmac emulating the Macintosh SE/30 computer.

The bootup sequence is displayed and the After Dark screensaver activates with the fish module. Credit: Mark Hellar.

Sterrett (Cont.): Taking those early design icons as an example, when Susan Kare let us explore her early designs viewing them was challenging because they existed on floppy disks, an old medium that is not readable on today’s computers. Moreover, the files were created using programs that no longer exist. In the end, our coworkers developed a system which presented an emulated Macintosh 128K (from 1984) on a web page that allowed us to view the contents of vintage floppy disks from our desktops on east and west coasts, compare notes, and exchange ideas. We may have built our teams in different ways but it was a thrill to watch them partner to take this on.

So, say a bit more about how things look today?

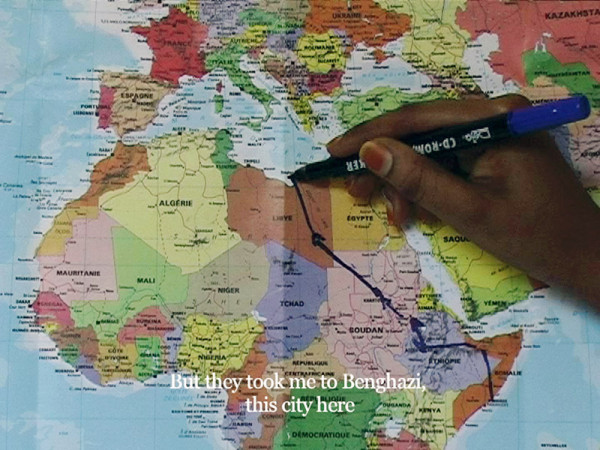

Coddington: I’d have to say that at MoMA there has been a flattening of hierarchies. By that, I mean broad populations are working across the museum, all with a vested interest in both access to and preservation of the media collections. The examples of this are legion, but one that comes to mind is the installation of Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Project (2016), an eight-channel video installation that traces simultaneously the illegal journeys of eight individuals who were forced by circumstances from their homelands.

Coddington (Cont.): Installing Khalili’s work in MoMA’s atrium involved the collaboration of curators, conservators, registrars, audio-visual technicians, and exhibition designers. The process began with the receipt of files on multiple file carriers and progressed to monitoring the display parameters regularly during the run of the installation. A vast number of decisions had to be made by multiple stakeholders, all of whom acknowledged each other’s particular knowledge and expertise. One thing that is necessary is to clearly locate leadership of broad media preservation policy with one department, which in our case is conservation. Colleagues from across the museum were, indeed are, vital to successful acquisitions and installations as well as defining programs and preservation goals. That said, when decisions needed to be made to advance the program, conservation was understood to be leading that collective effort forward.

Sterrett: How is this form of fluid operation different than before?

Coddington: It is also interesting to think about these shifts, for example, the flattening of hierarchies. Are they permanent? If so, how do we codify that kind of fluidity in our institutions and prepare everyone for this new state of affairs? Codifying fluidity sounds pretty oxymoronic at first. But you know, as we have been talking about this, I see this change in approach reflected more broadly in the field of conservation. We are becoming less dogmatic, less rules-based in our approach, and more risk-based in our analyses and recommendations. There is an open-endedness to what we have been talking about here.

Sterrett: What else has changed?

Coddington: You may give me some pushback on this, but I worry sometimes about documentation and our strong, strong emphasis on talking to artists, relying on them to answer all of our questions. I recognize the value of relationships with artists, but I wonder whether it is becoming an end in itself rather than the means to an end. Is this a hot topic?

Sterrett: I don’t think so. Say more.

Coddington: If the initial impulse to work more closely with artists was to inform the presentation and treatment of artworks, I can see a subgenre arising within conservation that is purely documentary. And I wonder if that is playing against something I see as the field’s bedrock, which is treatment. There’s obviously documentation as part of collection care, whether it’s traditional conservation or media conservation. So documentation as a means has always been with us in modern conservation practice but not as an end. If we lose sight of our defining purpose, treatment, if that becomes secondary for some element of the profession, I worry that it’s a kind of fundamental challenge.

Sterrett: So what I hear you saying is that this subgenre is putting some crucial part of conservation at risk. Perhaps I will push back since I see inviting the artist’s voice as coming from the same instinct as forming Team Media, in order to do our jobs a bit better. To gain knowledge about an artist’s practice and map it to what we do to treat artworks.

Coddington: Yeah, when you say “mapping it to your experience and knowledge in treating works of art,” that is the key for me. One needs that perspective to know what is relevant and not relevant information rather than just Hoovering it all up.

Sterrett: Discerning conversations are key. That goal is central to VoCA’s Artist interview Workshops, which have been operating with support from the Mellon Foundation for the last six years. Over that period of time we have seen it change from a workshop grappling with classic preservation challenges pertaining to unorthodox artist materials and obsolete technological mediums into a more open-ended workshop about engaged listening, guided conversations, establishing rapport, and the contours of memory. It’s about making dialogue a skill that operates alongside visual acuity, manual dexterity, or doing archival research and scientific analysis, something as useful as x-radiography or your favorite spatula.

Jim, MoMA received an award from the Mellon Foundation for the Media Conservation Initiative. What is it exactly and where do you hope we’ll be as a field when that effort concludes?

Planning for the media conservation workshop, “Getting Started: A Shared Responsibility, Caring for Time-Based Artworks in Collections,” The Museum of Modern Art, May 2-5, 2017.

Photograph © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Amy Brost.

Coddington: You, of course, were part of that first 2003 meeting that really focused me on the problem and subsequent ones we shared with colleagues from Tate, all of which became Matters in Media Art. We were interested in offering similar experiences to more colleagues; Mellon has funded an effort to do that through a series of training workshops. The first workshop was just completed at MoMA. The planning and workshop itself reflect what we have been talking about here. The workshop planning group draws from staff at public museums and in the private sector, from curatorial and technical colleagues, a cross-section of this kind of knowledge and expertise. In the planning, one thing we often came back to, at least those of us working in museums, was that this workshop is very much tracing our own history within our institutions. These things tend to unfold in almost predictable ways now. Somebody in the museum has the bright idea, “we’ve got a problem here with media conservation,” and they start to wrestle with the problem, and probably it starts in the conservation department, but maybe in the A/V department or curatorial. But wherever it starts, a person begins to wrestle with the problem and realizes she needs other people working alongside her, she needs to at least be talking to them and finding out what it is, and so a media working group, a media team, seems to always organically develop. I think that we’ve all been through this, so it’s not really unique to us. Our experience is indeed a more generalized one. The workshop is productive in that regard, because it was designed to support the cross-disciplinary development of curatorial and conservation partnerships. I mean, look, it is always important to walk the walk and not just talk the talk of collaboration.

Further Reading

On Matters in Media Art, http://mattersinmediaart.org

On MoMA’s Media Conservation Initiative, https://www.mediaconservation.io/

On SFMOMA’s Team Media, https://www.sfmoma.org/read/team-media-action-contemplation/

On VoCA Artist Interview Workshops, http://www.voca.network/programs/voca-workshops/

Main image

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, 2008-2011

Eight-channel video (color, sound), dimensions and duration variable

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fund for the Twenty-First Century

© 2017 Bouchra Khalili, courtesy of the artist

Installation view, Bouchra Khalili: The Mapping Journey Project

The Museum of Modern Art, New York (April 9 – October 10, 2016)

Digital image © 2017, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar