Calder’s Circus

The Artist as Reporter and Inventor

Calder’s Circus (1926-31) was created to be performed by the artist and only by the artist himself. Made primarily in Paris, when the young Alexander Calder lived there and during his frequent travels back to New York, Calder performed the Circus for colleagues, friends, artists, critics, collectors, and luminaries from the worlds of theater, art, and literature. He last performed his Circus from start to finish for the filming of Carlos Vilardebó’s Le Cirque de Calder (1961),1 though selected acts appear in Hans Richter’s film Alexander Calder: From the Circus to the Moon (1963).2

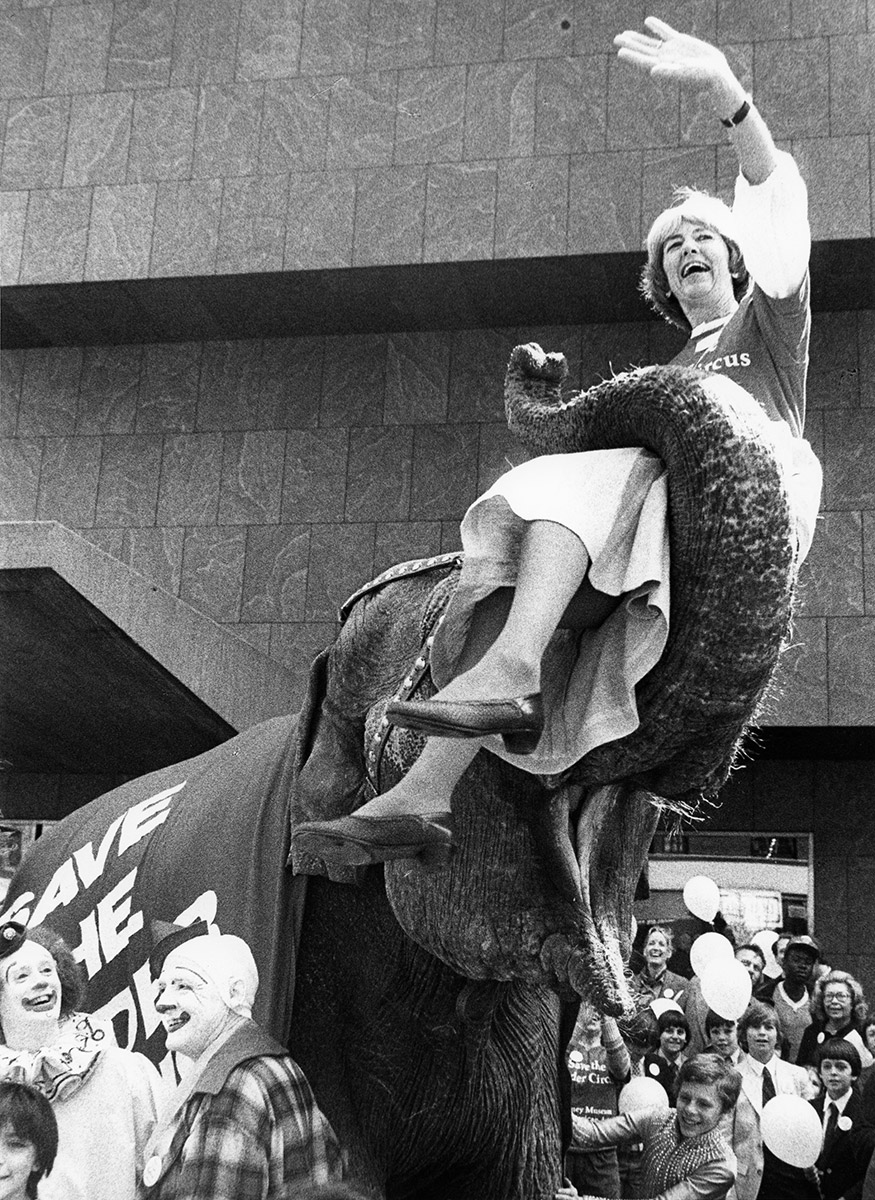

Calder’s Circus came into the Whitney Museum as a long-term loan in 1970, then as a permanent collection acquisition in 1983. The Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus itself took part in the fund-raising campaign to bring Calder’s Circus into the Whitney’s collection. Flora Biddle, grand-daughter of the museum’s founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney—then President of the museum’s trustees—rode one of Ringling’s elephants for a special, newsworthy event.

For the past four decades Calder’s Circus has been exhibited as a sculptural installation, the movement of its circus performers and animals arrested. This is for two reasons: first, because the Circus performance by Calder, who died in 1976, is now recognized as the type of Performance Art that may be presented only by its creator and no one else. And second, while present-day technologies and installation techniques might offer the promise of reanimating the figures by other means, preservation of many of their delicate materials precludes this option as well.

Calder’s Circus is a world unto itself, yet also has important implications for Calder’s breakthrough sculptures. He developed the Circus in the same period he created his open-form wire portraits, wire animal sculptures, and his now iconic mobiles. During this time, movement became Calder’s signature material. In the words of the artist: “Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.” Calder was clear in his intentions, and his accomplishments were paradigm shifting. His understanding and incorporation of movement’s animating force profoundly changed modern sculpture from static object to performative presence.

Beginning in advance of the exhibition, Alexander Calder: The Paris Years, 1926-1933 (Oct. 16, 2008-Feb. 15, 2009),3 curated by Joan Simon of the Whitney and Brigitte Leal of the Centre Pompidou, an interdisciplinary research team started exploring unknown or lesser known aspects of Calder’s Circus. The team included Eleonora Nagy, research conservator, Anita Duquette, archivist, and Joan Simon, curator-at-large at the Whitney from 2004-2009. This period of research allowed the archivist and curator to explore in depth how Calder re-interpreted and engineered his acts based on actual circus acts he had seen; it also allowed the conservator to see how the artist interpreted and reinvented these actions for his characters’ physical movements—and, above all, to integrate these findings.

After the opening of the exhibition in the fall of 2008, a grant was secured to continue the research through funding by the Getty Foundation. Additional funding was secured from The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation and the Robert Lehman Foundation by Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, Melva Bucksbaum Associate Director for Conservation and Research, to produce the video Conserving Calder’s Circus (2012).4 Alexander Calder’s performances of his various “circus acts” depicted in two films were analyzed, the phonograph records that he played to serve as musical accompaniment were conserved, a vintage record-player was purchased, and historical research began on each miniature “performer.”

Allowing our research to lead us wherever it did afforded us the means to discover how Calder made his Circus figures move, and—of equal importance—why these miniature figures so profoundly move us. The experience of witnessing Calder’s Circus affords us the same hopes and fears we experience at the real circus, and to the visceral understanding of engineering principles that aerialists embody, so that moving through time and space is accurately timed and a feat precisely accomplished. In comparing the movement of Calder’s figures as he animated them with the movements he actually saw, we gained a deeper understanding of Calder’s thoughts and actions, his sophisticated sense of humor, the conceptual underpinnings of his acts, and his own talents as a “barker,” pitchman, and ironic commentator on the performances presented.

This conversation about our long-term collaboration has been condensed and edited and incorporates some of our previous writing and discussions as well as our newest findings.

Eleonora Nagy: Calder’s Circus has traditionally been seen as separate little figurines, which have been addressed, exhibited, and treated as individual characters. From the outset, and in particular for the Getty Conservation project, the idea was to understand the Circus in the context of its making and as a complete entity, whether for conservation treatment or for installation. It has been a far-reaching project, combining rather than isolating the expertise of curator, conservator, and archivist. Of primary importance for our research was the interdisciplinary nature of Calder’s Circus, a gesamtkunstwerk synthesizing many mediums, among them non-traditional materials.

Joan Simon: In studying the Circus we recognized Alexander Calder as artist, artisan, and performer (his Circus’s “Ringmaster”); as a creator, engineer, and animator of figures and of the mechanisms that make them move. He was also its staging and lighting designer, musical director, narrator, and star of the films made of him performing his Circus. Above all, he was both reporter and inventor, basing his innovative miniature Circus on actual circuses he had seen in the U.S. and France.

The research project started with curatorial, conservation, collections management staff and the exhibition manager examining all of the elements of the Circus (including many of unknown purpose). This step was followed by archival research.

Anita Duquette: When Calder placed the work on long term loan to the Whitney in preparation for the 1972 exhibition and book Calder’s Circus (April 21-June 11, 1972),5 there were approximately 60 known parts of the Circus installation. However, there were also some 200 Circus elements and materials that had never been examined, including the five suitcases in which Calder originally transported the Circus during his travels and in which the work arrived at the museum.

After the artist selected the objects to be included in his Circus installation, the remaining Circus materials were packed up in the suitcases and sent to the Whitney’s off-site storage facility.

Installation view from 1985, Calder’s Circus, 1926-31. Wire, wood, metal, cloth, yarn paper, cardboard, leather, string, rubber tubing, corks, buttons, rhinestones, pipe cleaners, and bottle caps, Dimensions variable, 54 x 94 l/4 x 94 l/4 in. overall. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from a public fundraising campaign in May 1982. One half the funds were contributed by the Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Charitable Trust. Additional major donations were given by The Lauder Foundation; the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc.; the Howard and Jean Lipman Foundation, Inc.; an anonymous donor; The T. M. Evans Foundation, Inc.; MacAndrews & Forbes Group, Incorporated; the DeWitt Wallace Fund, Inc.; Martin and Agneta Gruss; Anne Phillips; Mr. and Mrs. Laurance S. Rockefeller; the Simon Foundation, Inc.; Marylou Whitney; Bankers Trust Company; Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth N. Dayton; Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz; Irvin and Kenneth Feld; Flora Whitney Miller. More than 500 individuals from 26 states and abroad also contributed to the campaign. 83.36.1‑72 © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, N.Y.

It was displayed in the lower gallery of the Whitney’s Marcel Breuer building at 945 Madison Avenue, which the museum occupied from 1966 to 2014. In the early 2000s, myriad Circus elements were catalogued and stored in special boxes designed by Whitney art handler G.R. Smith. Still other of the miscellaneous materials were not seen again until the summer of 2006 when the suitcases were re-opened during photography for the Calder “Paris Years” exhibition. The Whitney cataloguing system now designates the total number of Circus elements as 337.

Simon: Opening the boxes one by one sometimes revealed characters we knew well; other boxes contained wood sticks, small copper plates, mechanical gizmos, painted boards, felt, along with various odds and ends that likely had a function at one time in the performances.

Nagy: Anita provided us with historic photographs of the Circus’s prior installations, reviews, correspondence, and other documentation as well as new research materials discovered in the archives of other institutions. I examined individual objects and, in particular, found signs of their use by Calder that offered evidence of the artist’s hand not only in their making and repair, but also in how he generated his figures’ movements.

Simon: Correspondence from the 1920s and 1930s, other documents, and drawings were made available to us by the Calder Foundation. Carlos Vilardebó’s film of Calder performing his Circus, Le Cirque de Calder (1961), which had been shown at the Whitney and widely seen elsewhere, provided a number of clues to the mysterious items.6 However, we knew that this film did not include a number of known acts. Most important for identifying the large number of unknown items was Jean Painlevé’s Le Grand Cirque Calder 1927 (1955) that had been newly discovered by Nathalie Ernoult, a colleague at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, which served as the Whitney’s partner for the Calder “Paris Years” exhibition.7 To say that this film offered us a major breakthrough is an understatement.

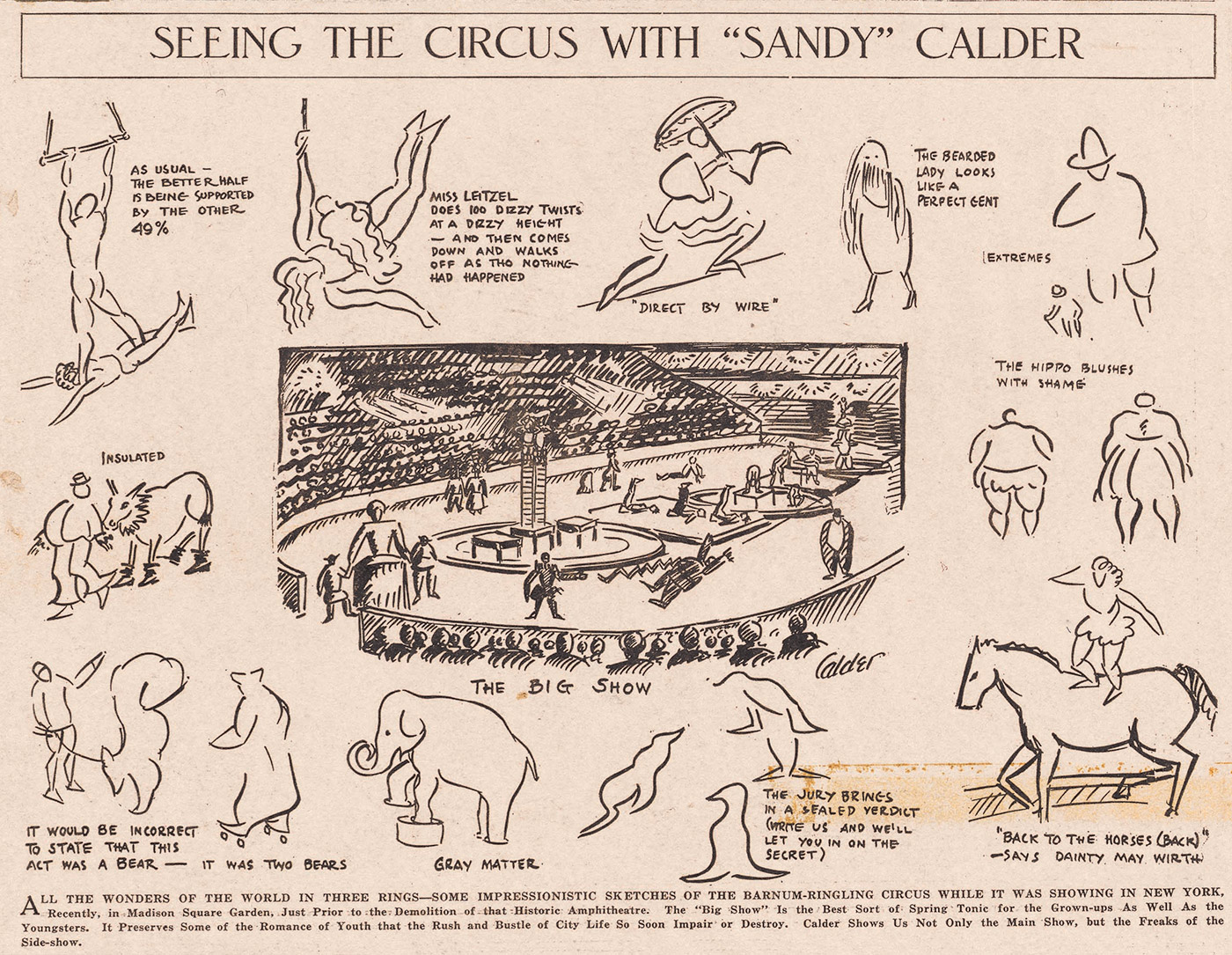

Duquette: In concert with looking at the Calder performance films, we also studied Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey material including posters, photographs, programs, and press clippings beginning with the period in 1925 when Calder spent two weeks illustrating the Ringling Bros. circus for the National Police Gazette. We had seen Calder’s lady bareback rider act in the performance films by Vilardebó (08:46) and Painlevé (01:15), and in his line drawing depicting a number of acts—Seeing the Circus with “Sandy” Calder, which was published in the May 23, 1925 issue—Calder had identified her, writing there: “’BACK TO THE HORSES (back)’—Says DAINTY MAY WIRTH.”

Alexander Calder, Seeing the Circus with “Sandy” Calder, May 23, 1925

National Police Gazette, Calder Foundation, New York

© 2017 Calder Foundation, NewYork / Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y.

Simon: On Ringling posters for this act showing the white horse with its female rider, we could see her identifying oversized pink bow, which matched the tiny pink bow Calder gave his miniature equestrienne…

Duquette: …which was found in one of the five suitcases and had not been displayed at the Whitney until the Calder “Paris Years” exhibition, where it was exhibited with other elements of the performed act: her horse, the rotary device that allowed horse and rider to circle the ring, the lady trainer, an odd wire with attached wheel, two copper plates, and a piece of string.

Alexander Calder, Prima Donna and Woman with Bow on Horse from Calder’s Circus, 1926-1931

Wire, cloth, wood, cardboard, paint, rhinestones and thread

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; 83.36.17, 83.36.58a-b and 83.36.28

Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

© 2017 Calder Foundation, NewYork / Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y.

Nagy: Each time we looked at these films, the different point of view of each director not only brought out different aspects of the act but also ancillary information, and triggered the impulse to find out more. The Painlevé film showed us that the two copper plates were part of the lady bareback rider act; and that one of them was deformed to a flat shape and needed repair. Based on the Painlevé film it was reshaped to its proper curved contour.

Simon: Only in the past week did I find a ca.1924 film of May Wirth performing exactly the act that Calder re-created (:001-:0048).8 It is just amazing to see how Calder engineered his characters, props, and mechanisms—so that his equestrienne could jump over a rope that lands under her feet and just above the horse’s back, as May Wirth actually executed the jump over an extended “line” of cloth. To accomplish this feat, Calder, with one hand, turns the crank that causes horse and rider to circle the ring, and in his other hand grips the far end of the rope extended by the lady trainer.

Duquette: This physically small equestrienne’s skills were touted on Ringling posters. One states: “MAY WIRTH THE GREATEST BAREBACK RIDER OF ALL TIME.” Another declares: “RINGLING BROS ARENIC SENSATION. WORLD FAMOUS EQUESTRIENNE.”

Nagy: Exploring these connections we realized that many other of Calder’s characters are based on real life performers. Through a vintage film of the Ringling performers participating in a Fifth Avenue parade, which Anita discovered, and in which a stilt walker strides across the avenue, we learned the likely source of Calder’s Man on Stilts (03:12-3:38).9 This white-clad figure is part of the Whitney’s Circus collection, but is never seen in action in either of the performance films. It may, however, be glimpsed in Vilardebó’s film when Calder turns to select material for his next act from a table laden with characters and props.

Duquette: Its image may be seen in a Herbert Matter photograph of Calder’s toys and Circus objects, published in the Matter-designed catalogue accompanying the 1964 Guggenheim Museum exhibition Alexander Calder: A Retrospective.

Nagy: From experimenting with the Man on Stilts’s range of movements and studying vintage Ringling photographs, I believe this character is Arthur Nelson of the Nelson Family Acrobats, based on his physical appearance and especially his white costume, but further research is needed to confirm the identity of Calder’s source.

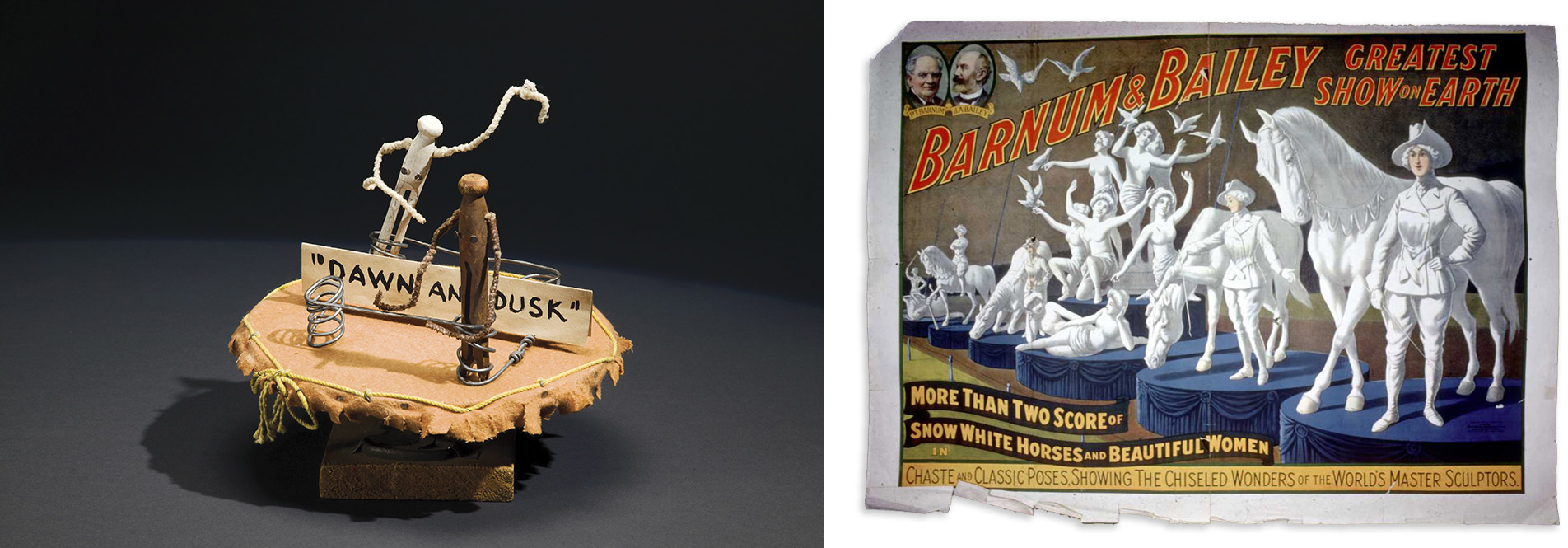

Simon: Anita’s discovery of posters for Ringling’s “Living Statues” or “Living Art” tableaux allowed us to identify the source of Calder’s “clothespin ladies.” Ringling’s women, seemingly nude, were in bronze-colored costumes and body paint to represent bronze sculpture or similar white costuming to represent marble. These correspond to Calder’s barely painted brown and white found-objects—wooden clothespins—signaled as female by two dots as breasts.

left: Alexander Calder, Clothespin Ladies: Clothespin figures, Sign “Dawn and Dusk” and platform, from Calder’s Circus, 1926 1931

Wooden clothespins, paint, pipecleaners and nails, 4 ½ x 2 ¾ x 2 ½ in.; paper and paint, 1 ¼ x 6 ¾ in.; wood, metal, fabric and string. 3 ¼ x 8 ½ x 13 ¾ in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 83.36.25.1; 83.36.25.5; 83.36.25.11 and 83.36.25.6

© 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. Photograph Sheldan C. Collins

right: Circus Poster, Barnum & Bailey: More Than 2 Score of Snow White Horses and Beautiful Women, 1916

Ink on paper, the Strobridge Lithographing Company, 30 x 39 ¾ in

The Ringling Museum, Tibbals Circus Collection, Sarasota, FL

Calder ignored Ringling’s high/low divide between acts that were performed in the main arena and those that were staged outside of it in the sideshow. He included both types of acts in his ring. In addition to the Bearded Lady and the Sword Swallower is Fanni, the Belly Dancer, one of the stars of Calder’s Circus (6:03-6:28).6 Moreover, looking closely at Painlevé’s film, we see how Calder, in his sequencing, celebrated and intimately connected his gyrating, barely clothed Fanni with his “high art,” abstracted “nudes.” At the end of Fanni’s exotic dance a blue circular curtain descends and envelops her. When the curtain rises, we see in her place the first of Calder’s four “clothespin ladies” allegorical tableaux, “Dawn and Dusk.”

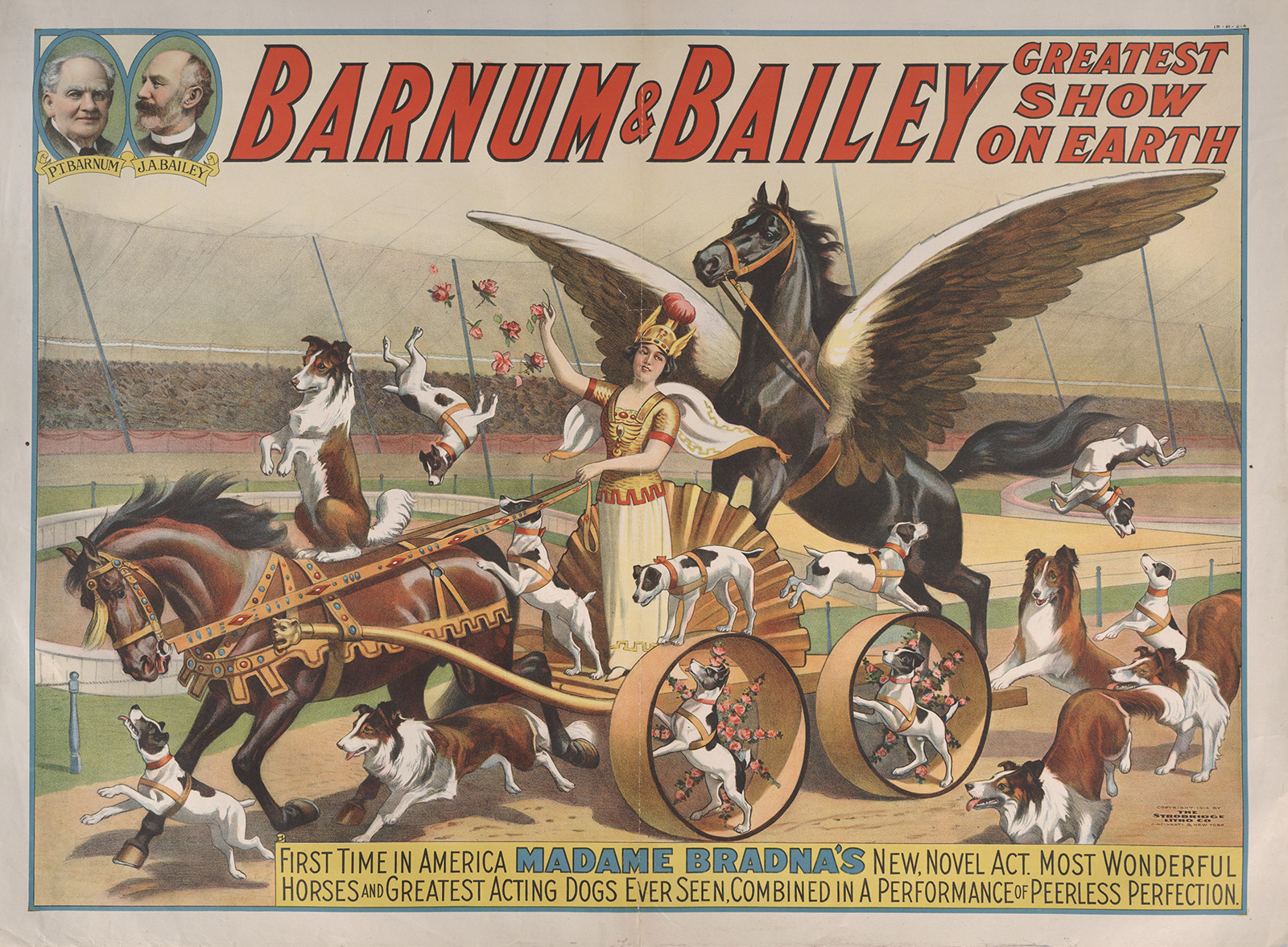

Nagy: Another Ringling poster allowed us to identify Madame [Ella] Bradna’s Ringling act as the source for Calder’s Pegasus.

Alexander Calder, Pegasus from Calder’s Circus, 1926-1931

Painted wood, wire, sheet metal and string, 13 1/4 × 16 3/4 × 7 7/8 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 83.36.27

© 2017 Calder Foundation, NewYork / Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y.

His Pegasus is borne on a chariot that, when in motion, also reveals small dogs almost impossibly running within and out of the chariot’s turning wheels. The Barnum and Bailey poster announces: “FIRST TIME IN AMERICA MADAME BRADNA’S NEW, NOVEL ACT. MOST WONDERFUL HORSES AND GREATEST ACTING DOGS EVER SEEN COMBINED IN A PERFORMANCE OF PEERLESS PERFECTION.”

The Painlevé film also allowed us most recently to identify a separate, small, metal dog as part of this act. The Calder act featuring Pegasus begins with the artist setting in place a glamorous, diamond-bedecked female figure. Then Calder introduces a little mechanical dog that, like one of the pull toys he had made for commercial production, eccentrically wobbles along at the end of the string that Calder holds. After leading this dog around, Calder brings it to rest at the feet of this lady, whom we now know to be based on Madame Bradna. In the last scene of this act, Calder also brings Pegasus to a full stop next to the little dog and Madame Bradna.

Duquette: Before we had discovered the Ringling “Madame Bradna” poster, the glamorous, diamond-bedecked lady in this scene had not been associated with the Pegasus act; she was identified with an act in which white paper birds flutter down from a birdhouse and land on her shoulder. Reviewing the Painlevé film once again, we see that Calder takes the lady from the “Bradna” act cluster of three elements (lady, dog, and Pegasus) as the scene ends and moves her to center stage to begin the “bird” act that immediately follows. It is such a smooth transition—and the elegant lady so closely associated with the birds—that understanding how Calder got from the dog act to the bird act tells much about how he operated his circus, often re-using the same figures. Calder employs the same horse, for example, in his cowgirl act, cowboy act, and the lady bareback rider act.

Simon: But here, it turns out, as I just discovered, Calder used the same female figure in two acts because, in reality at Ringling, Madame Bradna’s “act beautiful” as such acts were known, was famed for its thoroughbred horses, scores of dogs, and doves.

Circus poster, First Time in America MADAM BRADNA’s New Novel Act…, n.d.

Ringling Museum of Art, Tibbals Collection, Sarasota, Florida

Nagy: To compare the feats performed by actual acrobats with those performed by Calder’s, I first made a replica of one of his miniature acrobat acts, for study purposes only, and then invited real life acrobats (Jonathan Nosan, Ken Berkeley, and Matthew Cusick) to perform the same movements. With their input and our manipulation of the figures in ways that they said were humanly impossible, we concluded that some of Calder’s acts could not have been achieved in real life. Hence, Calder used his artistic freedom to embellish and enhance the visual experience of these acts (06:47-07:42).4

Duquette: Jean Lipman hired Marvin Schwartz to photograph some of the figures from Calder’s Circus in spring 1971. The photographer captured the artist moving these acrobats in ways unseen in the films made of Calder’s Circus.

Nagy: In addition to the relatively unorthodox means of hiring actual acrobats to better understand Calder’s Circus figures in motion for conservation purposes, we are exploring new tools to assess an object’s condition and measure changes over time, among them 3-D laser scanning, and photogrammetry. The combination of these techniques provides the most accurate, color rendered, three-dimensional documentation of the figurines. It enables us to see “topographic” details that we could not observe by examining them while holding them in our gloved hands; details that are—because of their three-dimensionality and problematic depth of field—also difficult to examine through microscopes.

Such documentation is of prime importance, especially for characters incorporating fragile cotton strings, silks, and inherently fragile leather where means to treat and retain parts of the original object are severely limited. For example, photogrammetry revealed that Calder had stuffed the tiny little tightrope dancer with pink fabric.

Photogrammetry also promises to be an excellent educational tool for museum-goers. It would allow the viewer to virtually turn a three-dimensional image of a figure upside-down, left and right, and zoom in and out, supplementing the single arrested pose on display.

Throughout our research we had hoped to more fully establish the frequency of Calder’s presentations and confirm more of the locations. We hope to explore this issue further by examining the many overlaid shipping labels on Calder’s valises, without physically removing them. To this end we are considering Terahertz imaging (THS), a radiation technology that, as an alternative to X-rays, permits high-resolution layered imaging of the interiors of solid objects. This technique may be likened to reading pages of a closed book. Another tool we are considering that may allow us to garner the texts on labels that are now illegible is the Video Spectral Comparator (VSC), a high resolution technique used in forensic science. In addition, we look forward to continue studying the musical instruments and audio components of Calder’s Circus, and perhaps presenting our findings in a video. Our understanding of the Circus remains incomplete without its important sound features.

Having embarked on some understanding of the roles motion plays in Calder’s Circus, a paradox for its custodians remains regarding its display. As sculpture, Calder’s Circus is in a state of halted motion; how do Calder’s miniature circus figures live on when they can no longer move?

Simon: For the Circus’s display in the “Paris Years” show, the goal was to return to the objects—the relics, in a sense, of its live performance—an understanding of their once-upon-a-time animation and to restore to the Circus its history and the contexts of its making by incorporating elements that had been newly identified.

A critical decision for the installation was to show the Circus act-by-act—with all the constituent props, accessories, and mechanisms—a presentation that had never been done before. We used the odd wood rods found in storage to create the “masts” (as Calder referred to them), doubling the height of his “tent” supports and also included the single tattered metal lamp also found there. Working with vintage Calder performance photos, we saw how the artist had used these elements.

The figures, importantly, were exhibited with the apparatuses that Calder had devised to make them move. And so the elephant was installed on the newly identified and related painted board with the mechanism Calder manipulated to have it stand up; acrobats with both the platform board and launching device that Calder triggered to hurl them into space; the equestrienne with her horse, lady trainer, the two curved copper plates, the odd wire/wheel attachment, a piece of cloth beneath which was the rotary device, its crank extending outside the ring so that Calder could turn it by hand.

If all the chosen acts were poised in static positions, our use of video allowed them to be seen in action. Near these acts, on the outside of the case, were small video monitors showing a related excerpt from the moving picture so that the visitor had a bi-focal view, both to the sculpture and to the act being performed.

Installation Calder’s Circus, 1926-1931 in Alexander Calder: The Paris Years, 1926-1933

(October 16, 2008-February 15, 2009), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Photograph Sheldan C. Collins

In addition, the fact that Calder performed his individual acts sequentially was highlighted by award-winning lighting designer Jennifer Tipton’s programming a subtle spotlight within the case to move from act to act.

Duquette: Calder’s Circus was a dynamic performance, an array of superbly crafted miniature sculptures, and at the same time was an astoundingly accurate representation of actual circus acts. None were more significant than those he saw at Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1925 which closed in May of this year, after 146 years as “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

Nagy: With regard to the Circus, we know there is much yet to be discovered.

Acknowledgments:

These Calder projects have been made possible by many institutions, foundations, and individuals. Among the many, special thanks go to Adam Weinberg, Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, Amy Roth, Hillary Strong, Barbi Spieler, Lauren DiLoreto, Stephanie Schumann, Anya Bondell, Flora Biddle, Eloise Owens, and Steve Berger; Alexander “Sandy” Rower, Alexis Marotta, Jessica Holmes, Terry Roth, and Lily Lyons, at the Calder Foundation; Elan and Jonathan Bogarin, of El Tigre Productions.

Endnotes

1 Carlos Vilardebó, Director. Cirque de Calder, (1961), 35mm, color, sound, two versions: 19 minutes and 28 minutes. Société Nouvelle, Pathé Cinema, Paris

2 Hans Richter, Director. Alexander Calder: From the Circus to the Moon, (1963). 16 mm, Color, sound, 12 minutes. Contemporary Films / McGraw-Hill, New York.

3 Joan Simon and Brigitte Leal et al. Alexander Calder: The Paris Years, 1926-1933. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art/ Yale University Press, 2008. French Edition: Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne/ RMN, Paris, 2009

4 Whitney Museum of American Art. Conserving Calder’s Circus, 2012. Video, color, sound, 12:45 min. (http://whitney.org/Collection/Conservation)

5 Jean Lipman with Nancy Foote, editors Calder’s circus. New York: Dutton, 1972

Exhibition curated by Robert M. Doty, with book by Jean Lipman, then head of the Publications Department at the Whitney Museum

6 Carlos Vilardebó, Director. Cirque de Calder, (1961), 35mm, color, sound, two versions: 19 minutes and 28 minutes. Société Nouvelle, Pathé Cinema, Paris. Carlos Vilardebó: El circo de Calder (1961). YouTube, Uploaded by Titulo Original, May 20, 2014. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4LdlxaxAFA)

7 Jean Painlevé, Director Le Grand Cirque Calder, 1927, 1955, 16mm film, color, sound; 45 min. Les documents cinématographiques, Paris. Alexander Calder performs his “Circus.” Whitney Museum. YouTube. Uploaded by Whitney Museum, Oct 23, 2008.(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t6jwnu8Izy0)

8 WIRTH, MAY, Australia’s bareback queen (USA, c.1924). YouTube, uploaded by Stleonm, November 9, 2010. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uc9F32fqzGM)

9 Circus parade for milk fund—outtakes (Filmed on April 23, 1923), Fox Movietone Newsreel (A5339). Silent, black and white. University of South Carolina, Moving Image Collections, Columbia, S.C. (https://mirc.sc.edu/islandora/object/usc%3A48758)

Main image

Alexander Calder performing Calder’s Circus at the home of Dr. Bernard Riess, near New Preston, CT

c. mid 1950s, Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Whitney Museum of American Art

Calder Research Archives, Photograph Dr. Bernard Nathanson