Building, Performing, and Translating the Negative

The Working Relationships of Schneider/Erdman, Inc.

In 1981, Gary Schneider and John Erdman founded a photography printing business in the heart of downtown Manhattan. Working with countless photographers, technicians, assistants, and other printers in the years that followed, Schneider/Erdman, Inc. produced iconic photographs and publications that defined an era.

The Harvard Art Museums recently acquired the Schneider/Erdman Printer’s Proof Collection, which includes nearly 450 printer’s proofs from the pair’s Manhattan-based photo lab. Together with test prints, business records, and archival materials generously given to the museums by the artists, the collection illuminates the lab’s three decades of work and has spurred a range of cross-disciplinary projects and new research questions. The collection will be featured in the museums’ upcoming exhibition and print publication Analog Culture: Printer’s Proofs from the Schneider/Erdman Photography Lab, 1981–2001, curated and edited by Jennifer Quick.

Earlier this year, Jessica Williams, the Agnes Mongan Curatorial Intern at the Harvard Art Museums, wrote a post for the VoCA Blog that explored the history of Schneider/Erdman, Inc. and how the upcoming exhibition aims to teach both students and the general public about the material, cultural, and social histories of photography. For this issue of VoCA Journal, Williams dug deeper into the topic and spoke with Gary Schneider about Schneider/Erdman, Inc.’s working relationships with photographers, companies, and technicians as well as how the nature of the collection has inflected the research for and direction of the exhibition.

Jessica Williams: Since you and John Erdman opened the lab on Cooper Square at the urging of friend and photographer Peter Hujar you’ve printed for a wide range of photojournalists, fashion photographers, and artists.1 For this conversation, I thought that we might discuss projects that required you to reach outside of the lab—your work with Brian Lanker and Eastman Kodak, collaborations with Tom Hurley at Laumont Photographics, and printing the camera art for Madonna’s Sex all leapt to mind.

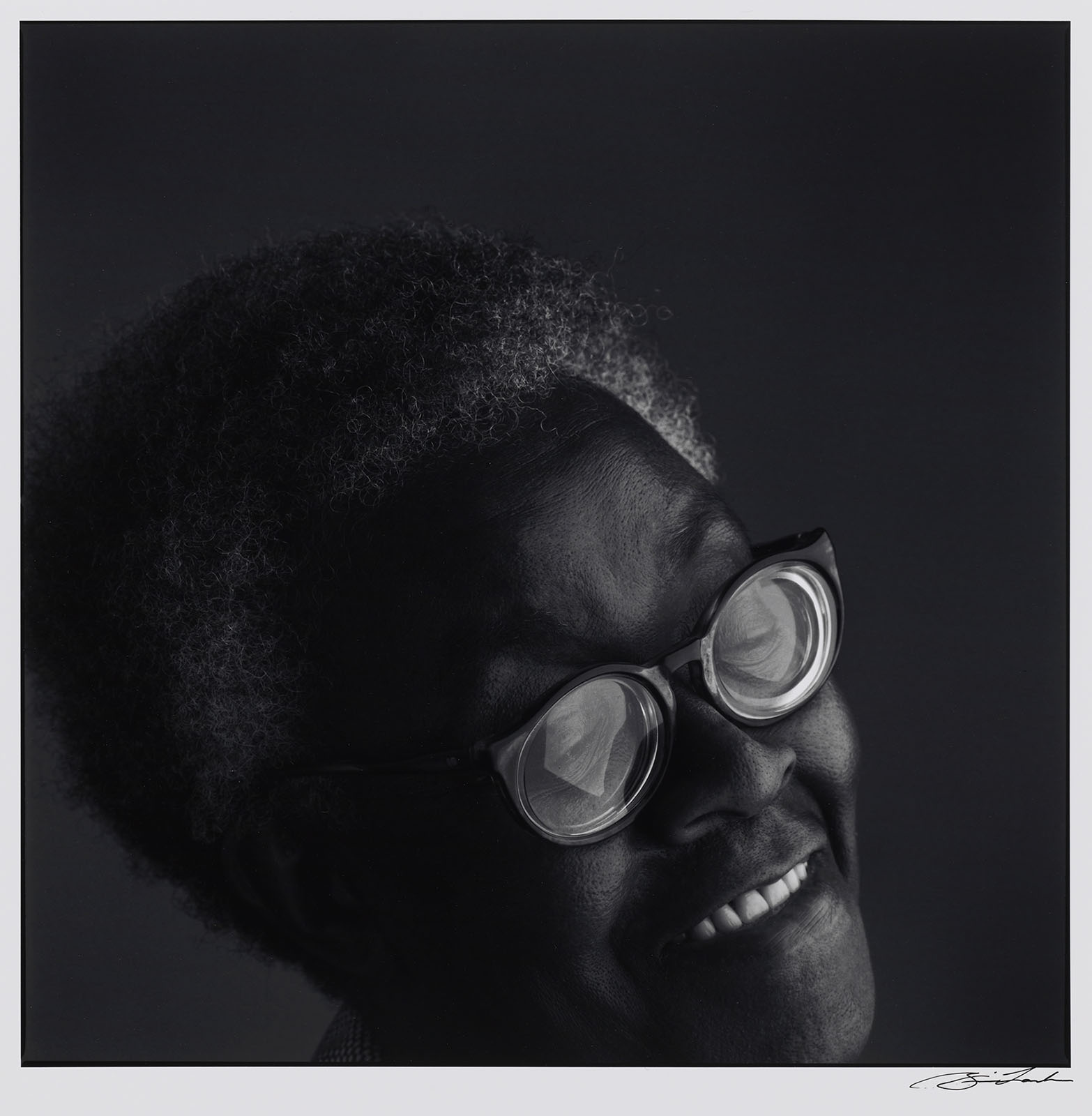

Gary Schneider: Let’s begin with Kodak. My relationship with Kodak deepened during the 1988 Kodak-sponsored Brian Lanker project, I Dream a World, which he shot on their new T-Max film stocks. I was also printing Brian’s images on Elite, Kodak’s new graded papers. Kodak had developed a suite of films in all formats, and I was having some problems with them. During the Lanker project, Kodak executives often visited the lab, and we would discuss their various papers and films. I had done many tests to see how different films compared with each other and what their attributes were, and I had issues with the new Kodak T-Max 400 film—it was very bumpy in certain tones. Kodak had instructions on how the film needed to be processed, but it didn’t work for me. I was really good at identifying when there was a problem, and I had suggestions on how to solve it. Eventually, I was brought to Rochester to have a conversation about the film and its tonality with Kodak’s technicians and scientists. This was huge for me. In the mid-1980s, analog photography was exciting; I was always dealing with the manufacturers about their materials. Kodak had changed the color of the base of their paper, Ektalure G; it changed how my prints looked. I complained about it, and Kodak said, “Well, it’s within our tolerances.” They started calling any of these quibbles that I had with them the “Schneider Tolerance Test.” I was somewhat proud of this.

Williams: When you visited Kodak’s facilities in Rochester did you do tests with their technicians in a darkroom?

Schneider: No, it was literally a Q and A in one of their large lecture theaters. Of course, they would talk in very technical scientific terms, and I didn’t have that language. I’ve never had that language, actually. I don’t think or talk that way. But we managed to communicate. I had already developed a different language to exchange ideas with artists. I didn’t come out of a technical school; I came out of the art schools Michaelis and Pratt and was taught by Peter Hujar.

Williams: I’ve certainly developed a new language for discussing prints over the course of our conversations this year. The ability to communicate the medium’s technical aspects in a way that doesn’t alienate audiences unfamiliar with the darkroom is something that I’ve been learning from you. The nature of the printer’s proof collection and conversations like this one are in part what led Jennifer [Quick] to want to move beyond discussions of the image and to delve into photography’s less explored material histories. In the print publication and through the related digital resource, we get into how the industry’s shifting materials opened new aesthetic possibilities while foreclosing others. As you were running up against various challenges, who were some of the people you turned to for more technical discussions other than the manufacturers, particularly during the lab’s transition from analog to digital?

Schneider: I talked to many specialists. In the beginning, I would consult John McElhone, photography conservator at the National Gallery of Canada, on my printing methods and storage for stability. The lab’s transition from analog to digital was facilitated by Tom Hurley. My relationship with him began really early through printing for artist Peter Campus.2 Peter was using a pre-Photoshop software to do scans and drawings for his early digital artwork, and those files would have been sent to Tom and turned into negatives (LVTs) so that I could make silver prints. That goes way back to 1989. So this started very early, printing in the darkroom but actually using files to work from. Before digital, there were retouchers I had worked with—Bishop Studios on Robert Gober’s untitled photograph of a bride, from 1992, for example—I made a silver print of the bride from a medium-format camera negative. The print was then retouched at Bishop Studios. I then rephotographed the retouched print to make a new large-format negative in order to print the final edition as well as a print for reproduction. With the digital age, all that would be replaced by Photoshop.

Williams: The labor that you’re describing and the exchanges involved in making prints often go unaddressed in art historical scholarship. Given our discussions about your relationships with different artists and technicians, have your thoughts on the issues of authorship or your role as a printer changed as the exhibition has taken shape?

Schneider: The process of looking at each of these relationships has certainly refined my understanding of the dynamics underlying each of the projects. I was never able to work with an artist who didn’t have a strong ability to see and understand his or her own work. With each of these authors I had as little as possible investment with how the final print would look. In my work as a printer, I was always searching for ways to have the voice of the author be fully realized without my authorial presence. How I got there was, I suppose, what I could bring as a craftsman. So the Nan Goldin is, I think, one of the more interesting cases in point because the black and white work was so early for her, but she had made these prints herself.

There’s a self-portrait of hers in Harvard’s collection that’s going to be exhibited. I didn’t print that image, but it’s a particularly beautiful print. She was locating the right density and contrast for the print without too much burning and dodging. When we first started discussing the project I asked her for as many prints as she had made so that I could use them as guides. She was, however, very self-conscious of her hand, of how she had burned and dodged the prints, so she didn’t really want me using them as guides. Her voice was very clear inside of her own prints, in how she had realized her images. It was very useful for me to then take how she herself had manipulated her negatives to make her prints and translate that through Agfa Portriga Rapid into these very much larger prints, the 16 x 20s. So that is a very straightforward interpretation of a dialogue with an artist, where I could bring my, I suppose, more tutored hand to the table and find ways to resolve the print. This question of authorship even comes up in how I make my own work—in how I think about my series of handprints, for example, as really a collaboration with my subject in their making a self-portrait under my supervision.

Williams: Were there other projects you undertook that necessitated particularly complex exchanges?

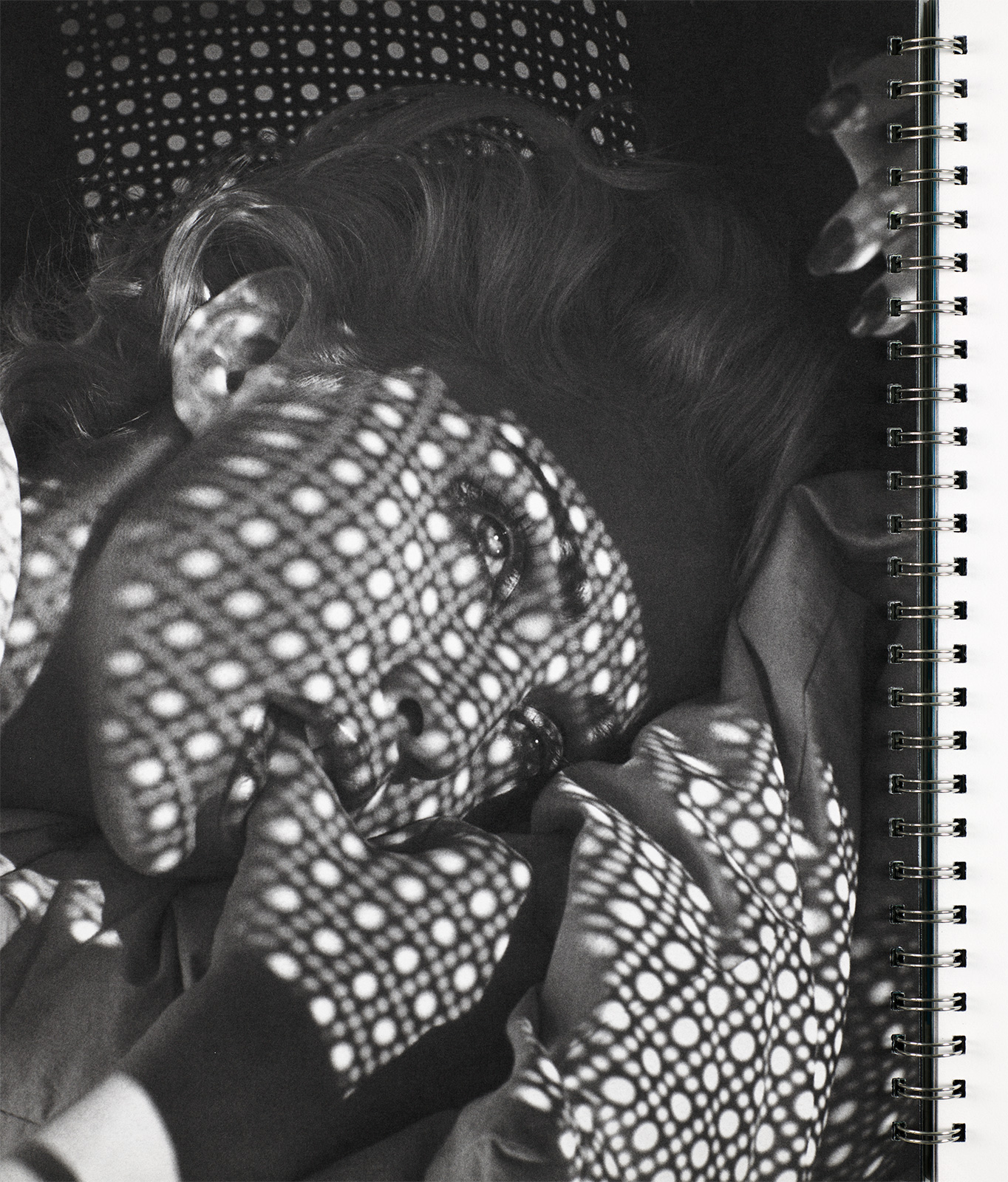

Schneider: Madonna’s Sex (1992) was a very complex and interesting project to consider with regard to authorship, particularly this idea about authorship being interdependent or somewhat shared across disciplines. With Sex, the negatives had already been processed at Steven Meisel’s lab. I’d never worked for Meisel before. Nicholas Callaway came to the lab and said that there had been a major contract breach with Madonna’s book. He had come to us because we were famous for our extreme discretion. He said, “You’ll have to sign a non-disclosure agreement, which means that nobody, other than you and anyone else who signs this, will be responsible for anything that might be leaked before the book is published.” I said, “Look, we can’t do that to my technicians because I don’t want them to carry that responsibility.” But Callaway walked to our bookshelf and pointed to some of the most beautiful books in my collection, saying “I published these.” When he told us that Richard Benson and Thomas Palmer would be doing the negative separations and listed the phenomenal team of people, including the designer Fabien Baron, who would be involved with the book, John and I agreed.

Madonna’s book was being produced by all of the top people in their fields. The team and the collaborations were the most interesting aspects of this book for me. The negatives would be brought in, and I would be printing all day. John would have to dry the prints after everyone had left the lab. Meisel’s assistant would drop off the negatives for the next day’s printing. Baron’s assistant would come after everyone had left, and we would have discussions about what the prints should look like. It was exhausting and exciting, and the requirements were technically really tough. Benson refined negative separation for reproduction to an extraordinary level, and his expertise contributed to the book in profound ways—it’s an amazing technical feat and truly visionary in terms of its production.

Williams: One of the graduate students helping with the upcoming exhibition, Davida Fernandez-Barkan, is contributing a case study on Madonna’s Sex for the museums’ forthcoming digital resource related to the printer’s proof collection. Like Sex, the collection serves as a microcosm for 1980s-90s photography—as an industry but also as a burgeoning field. In many ways, the nature of the collection has pushed us to delve into the less explored material histories of photography and to employ new theoretical approaches from a range of disciplines (studies in language and performance, for example). Over these past months, we’ve spent a lot of time discussing this collection’s pedagogical potential and how we might best be able to relate your and the lab’s histories. When you and John started retaining printer’s proofs, did you ever consider that they might be used collectively in teaching?

Schneider: We originally thought of the collection as a study collection, to be conserved as a control set of prints. After my 1996 “Light Conversation” at Harvard with former photography curator Deborah Kao about my own work, John and I understood how a research collection can be used in teaching. In the museums’ Mongan Study Room, we saw prints presented unframed on easels. Students were able to examine them as objects, just as John and I had learned by unframing prints at auction house previews. It was Debi who realized how useful the in-depth nature of the printer’s proof collection might be as a teaching collection. Her interest began while researching her survey exhibition of my work in 2003. In retrospect, the range of authors we worked for has proved to be a valuable sampling of a few interdependent communities centered in New York, mostly in the East Village. And it is becoming more apparent through all of the research being done for the book, show, and online resource that these communities of artists and photographers are a representation of the 20 years that made up the ’80s and ’90s (although I never stopped printing; prints beyond that period will also be presented in the upcoming book, site, and exhibition).

1 Peter Hujar was a New York-based photographer best known for the poignant portraits he made throughout the 1970s and 80s. For more information on Hujar, see the latest publication on the photographer’s life and work, Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, ed. Joel Smith (New York: Aperture, 2017). For more on Schneider’s personal and working relationships with Hujar, see Jessica Williams, “Printing and the Urgency of Translation: Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, and the Task of Schneider/Erdman, Inc.,” in Analog Culture: Printer’s Proofs from the Schneider/Erdman Photography Lab, 1981–2001, ed. Jennifer Quick (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Art Museums, 2018).

2 Peter Campus is an American artist who has creatively experimented with video and new media since the early 1970s.