Beyond Compliance

Teaching Disability Subjectivity in Museum Studies

In the spring of 2020 I taught a course at Purchase College called “The Inclusive Museum.” The aim of this class was to reimagine ways of thinking about the body and envision alternative modes for museums of modern and contemporary art to account for disability. I hoped to explore difference and embodiment in US museum studies education and praxis.

“The Inclusive Museum” drew from my own experience of mobility impairment. Born with mild cerebral palsy, I use an assistive device in order to walk, have poor balance, cannot walk or stand at length, and need to rest frequently. To people like me, museums and galleries that emulate the white cube esthetic first described by Brian O’Doherty almost fifty years ago are often hostile environments. One of my most common museum experiences is the hunt for hidden or distant elevators—these often require longer walks than taking the stairs, even as these tend to dominate majestic but older public buildings. Because standing at length can be painful for me, finding someplace to sit is crucial to my museum-going experience. The lack of seats or benches, whether stemming from exhibition design or curatorial choice, can make my visits excruciating. While simple amenities like seating are not utterly ignored in museums, I remain constantly surprised by the low priority of such needs.

This course title refers to “inclusivity” with a specific focus on disability; it acts to complement courses that highlight issues of race, decolonization, and other diversity and equity issues in museums. I believe that the shortage of creative approaches to teaching about disability in museum studies is a problem. Indeed, museum studies as a field does little with disability even on a compliance level. A 2010 Project Access study by Art Beyond Sight noted that there were no mandatory or elective classes at the sixteen universities surveyed in this area, and most only touch on the topic peripherally.1 The situation has changed very little since then. For me, this has posed an ongoing question about the place of the body in art museums. The class aimed to address these questions by concentrating on three themes: neutrality and representation, embodiment and access, and subjectivity in vanguard art.

Museums and Neutrality: Which Bodies Matter

“Why do some bodies matter more than others?”

–Nirmala Erevelles, Disability and Difference in Global Contexts

In the past ten years, a vigorous debate around museums and their politics has fueled reappraisals of contemporary art institutions’ fundamental missions. “The Inclusive Museum” opened by considering not only museums’ treatment of political work by vanguard artists but also explored the nature of the museum as a civic and cultural institution. With #MuseumsAreNotNeutral and #DecolonizeThis and the broader effects of the #MeToo movement pushing institutional reappraisals within the art world, we discussed how well museums are reaching the publics they aim to serve. The course hinged on the politics of embodiment and Nirmala Erevelles’ rephrasing of the question “Why do some bodies matter more than others?”2

Erevelles builds on post-structuralist theory, suggesting that disabled bodies are “texts for understanding social institutions, social discourses, and social practices.”3 This assertion lead to a core question throughout the course: How might museums assume that some bodies matter more than others—and why might that be?

With this question in mind, the class examined the role of identity in museum culture. Ground-breaking work in the field has revolved, for example, around disabled bodies and their representation in museum settings. In “Beggars, Freaks and Heroes? Museum Collections and the Hidden History of Disability,” Richard Sandell, Annie Delin, Jocelyn Dodd and Jackie Gay describe a research project conducted by the University of Leicester Research Center for Museums. Seeking to discover “the hidden history of disability,” the authors link representations of disability and people’s lives with the new museology.4

Richard Sandell, Jocelyn Dodd, and Rosemarie Garland Thomson’s Re-Presenting Disability (2010) expands this premise by analyzing case studies ranging from a new musicological presentation of Joseph Merrick’s story to presentations of disabled people at Angkor Archeological Parks’ Land Mine Museum.5 These readings pushed the class to explore the museum as an agent of change, not only through artistic representations of individuals but also, as Katherine Ott’s “Collective Bodies: What museums do for disability studies” argues, a museum can suggest new and different contexts for re-presenting stereotypes. As demonstrated by the Smithsonian’s online exhibition “Everybody: An Artifact History of Disability in American History,” the class examined how material culture can provide especially potent representatives of disabled life experiences.6 As Ott states in her essay,

“A clever curator and designer can turn stereotypes and assumptions on their head, propelling the visitor inside the experience of someone they might otherwise pity or ignore. For example, the disgust some visitors feel about artificial eyes might lead to curiosity and understanding when the acrylic eye has the logo of a football team laminated on it. In a willing museum, aversion can be turned into subversion.” 7

Ott’s comments proved prescient when students voiced near universal repulsion when viewing an artificial eye; nevertheless, when the class saw an acrylic eye painted with a Chicago Cubs logo online as part of the “Everybody: An Artifact History of Disability in American History,” the aversion changed into fascination. To further interrogate issues of representation, students brought in objects of disability from their own lives. Ranging from pill boxes to eyeglasses, canes to orthotic shoes, the class discussed how these objects might be curated in a museum context. The project helped students critique their understanding of disability itself, allowing them to see the contingency surrounding conditions of disability now and throughout history.

Museums, Normalcy, and Access: Making Bodies Matter

“I never get to lose myself in a picture, or wander in a reverie … I am always, ALWAYS aware of my body, how it’s blocking people, how it’s taking up space, how it’s inconvenient and cumbersome.”

–Ciara O’Connor, “Wheelchair user blasts Eliasson Show at The Tate Over Rampless Work”8

As the class discussion began to challenge the social construction of a “normal” body, “The Inclusive Museum” continued into a second module revolving around normalcy and access. Much work in disability studies reveals that examples of “normal” are in fact quite fluid; normalcy is a malleable concept situated in time and space. As Lennard Davis notes, “‘[t]o understand the disabled body, one must return to the concept of the norm, the normal body’.”9

Davis’ “Constructing Normalcy,” in Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body helps historicize the “invention” of normal, especially by describing efforts to shape generalized concepts of an ideal into a world-shaping imperative. Davis notes how this conception takes hold in the nineteenth century, specifically citing the influential work of Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet and the eugenic significance of such standards and measures when used by scientists like Sir Francis Galton. Not coincidentally, the rise of physical and performance standards in the nineteenth century occurred just as the modern museum began to take shape. Combined with ideas of aesthetic viewing—and bodily detachment—such views began to shape the very way in which art museums have been conceived and continue to be constructed to this day.

Davis’ historical critique led the class toward a broader discussion of how reflexive normalcy influences museum access. In recent years, examples of the problems confronting disabled people in museums have peppered the art press. Olafur Eliasson’s Your Spiral View (2002), a work accessible through a set of steps, inspired an outcry when it was shown at the Tate Modern. “In a museum, we all move as if we don’t have a body…” reads one of the many texts included in the exhibit. After she was unable to guide her wheelchair into the work, journalist Ciara O’Connor pointed out that “you only produce, curate, exhibit art for certain bodies. Fuck you for assuming that everyone who likes art and museums gets to ‘move as if they don’t have a body’.”10

While a broader view of bodies and normalcy helped orient the class, Tanya Titchkosky’s The Question of Access: Disability, Space, Meaning11 brought this focus directly toward imbalances of power. This text allowed a broader discussion of how received ideas of normalcy can also shape our awareness of who is included—or excluded. As Titchkosky notes, access “is an interpretive relation between bodies. In this conception, we can … discover how we are enmeshed in the activity of making people and places meaningful to one another.”12 This theoretical basis allowed the class to approach a broader institutional critique that in turn raised a series of questions about how bodies—and access—can present challenges and opportunities in a museum setting. How much should a museum be dedicated to protecting artistic patrimony? To what extent should it facilitate better forms of access to its publics? Is this a zero-sum game?

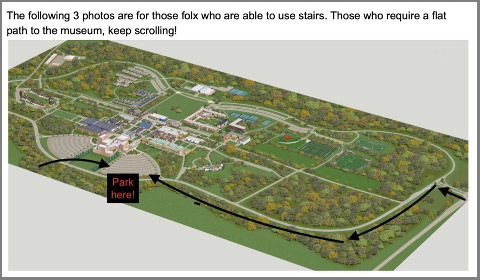

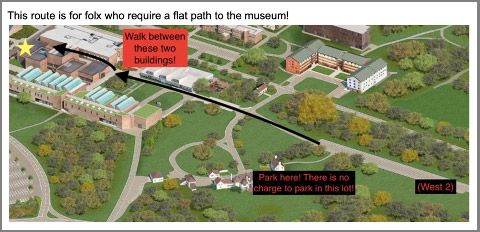

The recent preponderance of museum “Access Checks” allowed us to foreground practical applications of these questions. The Smithsonian’s Guidelines for Accessible Design proved a crucial touchstone;13 other texts included Carmen Papalia’s “New Model for Access in the Museum”14 and Carolyn Lazard’s “Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice.”15 Students produced critical maps documenting and analyzing access in and around the campus’ Neuberger Museum, often challenging mapping conventions in order to give visibility to the experience of people whose bodies don’t conform to standards or whose actual experiences might differ from that outlined in museum publications. In a particularly potent exercise, students recognized how broken elevators, malfunctioning doors, and lack of accessible parking all add up to profoundly alienating museum-going environment. Several students reported that museum officials questioned their visits and what they were doing while doing their assigned access checks. The response from officials (“A whole class on the ADA?”) led to surprising encounters with museum professionals and an ongoing discussion regarding the nature of museums themselves.

Subjectivity, compliance, and contemporary art in the museum

“…legal standards are a minimum. Museums and those responsible for them must do more than avoid legal liability, they must take affirmative steps to maintain their integrity so as to warrant public confidence…”

–American Association of Museums, “Code of Ethics for Museums”16

Despite their avant-garde embrace of transgressive concepts and gestures, many museums of modern and contemporary art omit or overlook the disabled body. Recent work by artists whose embodiment in most cases challenges normative notions of ability has both challenged standard museological practice and pushed museums and galleries to become more inclusive; the final course module sought out investigations of embodiment and access as experienced and critiqued by contemporary artists. Specific works included Park McArthur’s Ramps (2014), an exhibition of temporary access ramps requested by the artist so she could enter and exit art spaces across New York and New England, and Carmen Papalia’s Guiding String (2015) installations at the Model Contemporary Art Center in Ireland, a series of cords tied to museum fixtures that helped Papalia, who is also visually impaired, feel and move around the institution.

Carmen Papalia, Guiding String, 2015

Photo by Kristin Rochelle Lantz, Courtesy of the artist and Model Contemporary Art Center, Sligo IE

To reinforce these analyses, a series of guest speakers, each of whom has worked to understand and critique museum culture and its approaches toward disability culture, helped challenge students’ readings and perceptions. Speakers included artist and museum educator Ezra Benus, artist Hannah Sheehan, critic and editor Emily Watlington, and artist Shannon Finnegan.

As the class moved to remote learning due to COVID-19 restrictions, we continued to explore the creative potential of accommodations legally mandated for museums. The Zoom format enabled an extended alt-text-as-poetry workshop with Shannon Finnegan, and the course concluded with a frank—remote—conversation with Francesca Rosenberg from MoMA’s education department. The history of that institution’s work on disability, the realities faced by organizers after years of struggles for funding, and the current and future forecasts for change in a post-COVID world gave a new urgency to the discussion. The problems with budget and staff reductions—particularly in education departments—are daunting. Yet the promise and potential of new ways of engaging in online learning appear exhilarating. But also, a number of students found this course important in considering their own subjectivity and embodiment. A number are now writing independent thesis topics that grew out of the class. As one asserted in course evaluations: “this class changed my life …”

References

1 Nina Levent, Joan Muyskens Pursley, and Joseph Wapner, “Museum Studies Programs and the Need for Training in Disability and Inclusion,” Art Beyond Sight: 2012, 6.

2 N. Erevelles, Disability and Difference in Global Contexts: Enabling a Transformative Body Politic (Palgrave Macmillan US, 2011), 6.

3 Nirmala Erevelles, “Understanding Curriculum as Normalizing Text: Disability Studies Meet Curriculum Theory,” Journal of Curriculum Studies 37, no. 4 (July 1, 2005): 423–24.

4 Richard Sandell et al., “Beggars, Freaks and Heroes? Museum Collections and the Hidden History of Disability,” Museum Management and Curatorship 20, no. 1 (January 1, 2005): 5–19.

5 “Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum, 1st Edition.

6 “EveryBody: An Artifact History of Disability in America,” EveryBody: An Artifact History of Disability in America, accessed October 14, 2020, https://everybody.si.edu/.

7 Katherine Ott, “Collective Bodies: What Museums Do for Disability Studies,” Re-Presenting Disability, September 13, 2013, 275, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203521267-30.

8 “Wheelchair User Blasts Olafur Eliasson Show at Tate Modern over Rampless Work,” accessed October 14, 2020, http://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/wheelchair-user-blasts-olafur-eliasson-show-at-tate-modern-over-rampless-work.

9 Lennard J. Davis, Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body (Verso, 1995), 23.

10 “Wheelchair User Blasts Olafur Eliasson Show at Tate Modern over Rampless Work.”

11 Tanya Titchkosky, The Question of Access (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011).

12 Titchkosky, 3.

13 “Accessible-Exhibition-Design1.Pdf,” accessed October 14, 2020, https://www.sifacilities.si.edu/sites/default/files/Files/Accessibility/accessible-exhibition-design1.pdf.

14 Carmen Papalia, “A New Model for Access in the Museum,” Disability Studies Quarterly 33, no. 3 (May 12, 2013).

15 “Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice,” accessed October 14, 2020, https://promiseandpractice.art/.

16 “AAM Code of Ethics for Museums,” American Alliance of Museums (blog), December 12, 2017, https://www.aam-us.org/programs/ethics-standards-and-professional-practices/code-of-ethics-for-museums/.

Main image

Park McArthur, Ramps, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York

Image description: An installation photo of “Ramps,” by Park McArthur. Inside of a brightly lit room with white walls a loose grid of portable ramps cover the majority of the room’s black concrete floor. All of the ramps lie flat on the ground except for one which leans against a wall. On the wall opposite, two parking signs hang high at the wall’s top edge. The signs are blue and hold no lettering or textual information.