Between thought and expression lies a lifetime

The Lou Reed Archive at the New York Public Library

In 2017, the New York Public Library

announced the acquisition of Lou Reed's archive,

a tremendous trove of material – really materials –

that poet and songwriter Lou Reed

collected during his lifetime as a working musician.

As I read the early articles published about the archive, I wondered

what his collection contained and what story

its contents would tell.

But this story really starts with Laurie Anderson, the artist, musician, and Lou Reed’s life partner. He left his entire studio and office to her. Even though we all probably will have or have broken down a family house or home of loved ones, it’s evident that this was on a different level.

Loss and recovery, motivations and actions are complex. Anderson expressed this in Everything Is Flowing, a composition for the Kronos String Quartet she wrote in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. The storm destroyed her archives, her equipment and performance props in her Canal Street basement close to the Hudson River in 2012. She wrote:

I went down to the basement

Everything was floating

Lots of my old keyboards

Thirty projectors

Props from old performances

A fiberglass plane motorcycle

Countless papers and books

And I looked at them floating there

In the shiny dark water, dissolving

All the things I had carefully saved

All my life becoming nothing but junk

And I thought how beautiful

How magic and how catastrophic1

What Anderson would do with Reed’s materials, and what she actually did, sprang from many sources: her Buddhist practice, her devotion to Lou Reed, her life as an artist, her extensive experience in media art, her pride in New York, and her generosity in making Reed’s collection public.

In Lou Reed: Caught Between The Twisted Stars, the exhibition held at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts from June 9, 2022–March 4, 2023, there was a lot of love and dedication for Reed on display. You can see it in the tremendous effort to bring this collection to the public and you can see it through the songs, poems, and eyes of Lou Reed himself. The process and effort it took to bring Reed’s collection to the library had a lot to do with our personal and public commitment and what it means to collect and care for our culture, especially about a significant artist’s life. A process further intensified by the fact that born digital works may need to continually migrate to future formats and technologies that haven’t even been invented yet.

Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars (installation shot)

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center, New York

June 9, 2022 – March 4, 2023

Photo by Max Touhey, Courtesy of NYPL

There are three key people I spoke to about how Lou Reed’s archive became part of the collection: Archivist Don Fleming; Jonathan Hiam, former New York Public Library (NYPL) Curator of the Music and Recorded Sound Division; and Kevin Parks, the current Curator of the NYPL Music Division, who joined the library after Lou Reed’s acquisition. What follows are excerpts from those conversations, held over Zoom between March-May 2023.

I began my research asking Jonathan Hiam how the collection came to the library.

It would be a tall order to turn Lou Reed down in New York. I mean, any place that respected New York and what Lou meant to it, would do what they could to make it happen. Deciding to take the collection was not going to be a difficult decision. It was more a question of just figuring out all the basic logistics.

– Jonathan Hiam 2

Kevin Parks further described the contents.

The collection’s extremely large. 227 boxes. Just a massive amount of material. And that already just in and of itself makes it difficult. And then it’s a collection that spans from the early sixties to just literally a few years before Lou Reed passed. There’s an incredible parade of different formats and things. It’s actually staggering how many different audio and video formats appear in the Lou Reed archive.

– Kevin Parks 3

There are over 600 audiotapes in the Reed Collection4 , not including video and digital photography. Early on, Anderson hired archivist Don Fleming to help her assess the collection.

Among the goals of the cataloging of the papers, photos, and media, I wanted to establish how much original audio we could find. I knew we wanted all the audio transferred so that we could think about what we would do with it, what the collection consisted of before it ever went to wherever it was going.

– Don Fleming 5

The treatment for audio media is varied and sometimes complicated. The collection has multiple formats of analog and digital audio files of performances and rehearsals, including ProTools digital sound mix files, representing fifty years of changes in recording technology. While some formats can be repaired relatively easily, splicing analogue audiotape back together for example, other formats are more fragile. DATs (Digital Analogue Tape) degrade quickly. Born digital sound files, .wav’s, and .mp3’s, can be completely lost when the file is corrupted.

Don worked with Jason Stern and Jim Cass, Lou Reed’s assistants, two to three days a week for over a year. Fleming transferred all Reed’s analogue audiotapes with Steve Rosenthal in Brooklyn at MARS (MagicShop Archive and Restoration Studios).

It was in 1999 at Rosenthal’s former Soho recording studio the Magic Shop that Fleming stumbled upon piles of ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax’s recordings on the desk of Steve Rosenthal, Magic Shop’s owner and engineer.

In fact, that’s how I started working on Alan Lomax’s archive. On Steve’s desk he had DATs (Digital Audio Tapes) of Alan Lomax transfers. And he said, ‘Oh, I’m working with his daughter and they’re here in the city. You should meet them.’ And so I met them and ended up in that world, thanks to Steve.

– Don Fleming 5

Don became acutely involved in Alan Lomax’s Global Jukebox, a pioneering interactive web archive of hundreds of tapes from ethnomusicologists around the world. Listeners access specific audio samples using an online map interface that tracks the ethnic and geographic journeys of instruments and song forms.

When I told Laurie about The Lomax Archive and what we did with it. She loved that. She immediately got it. She liked the idea to have [Lou’s archive] accessible for research and wanted as few restrictions as possible, which as I knew would be the hardest part, to allow access to Lou’s collection online as well as in the library.

– Don Fleming 5

Before Anderson approached Don, she already had a few ideas about where she could take the collection. One was to build two collections, hers and Lou’s, in the shape of interlocking, inverted L’s. But starting from scratch and staffing two independent archives seemed overly complicated. Another option, apparently seriously considered, was to just set it all on fire. Burn everything.

Anderson and Don compiled a short list of institutions and began contacting them. Discussions progressed with The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, but, according to the New York Times, “Anderson changed her mind in 2015 after a law passed in Texas allowing people to carry handguns on college campuses. ‘I called them up,’ she recalled. ‘This thing we’ve been talking about for a couple years? It’s off. Because of guns.’” 6

__________

The fact that Lou Reed ended up at one of the world’s foremost research libraries in New York City makes a lot of sense. Reed is a consummate New York artist who connects so much with the Performing Arts Library Collection. The library has made a concerted effort since the 1930’s to collect American music. A significant aspect of the NYPL collection is experimental music, much of it taking place in New York. Reed fits this rubric too, through his associations with John Cale, Tony Conrad, LaMonte Young and the art world.

Jonathan Hiam was one of the people responsible for bringing Reed’s collection into the library.

When I started at the Performing Arts Library in 2008, collecting American music was part of my job. We had a mandate at the time to focus our collections on New York. I wanted to pinpoint some New York artists that I thought would be important [to the collection]. One of the first people I reached out to was Lou Reed. I didn’t know him. I didn’t know any of his people. I connected with Andrew Wyley, his literary representative, this is probably 2009. Wyley got back to me pretty quickly, the language he used was, “Lou wasn’t ready to place the archive.” Then after his death, it was Laurie who reached out to us, completely independent from my prior exchange with Wyley – I doubt if that conversation ever got any further than with Lou.

– Jonathan Hiam 7

Hiam’s intuition was right about the significance of placing Lou Reed in the NYPL collection.

Once you step back, you see how squarely it fits in… as part of a songwriter tradition, right down to Reed working with Pickwick Records. We had always collected popular music that tied to songwriting traditions like Tin Pan Alley, the Brill building. And so it fits. His collection is wonderful in documenting the recording industry…. What makes the Reed collection unusual is that it was a rock and roll star’s, which is not the ordinary thing. Just the sheer size of it and the fact that so much of it was audio and moving image media, that’s not like a lot of the stuff from a jazz or classical musician we’ve taken in, which would be paper.

– Kevin Parks 8

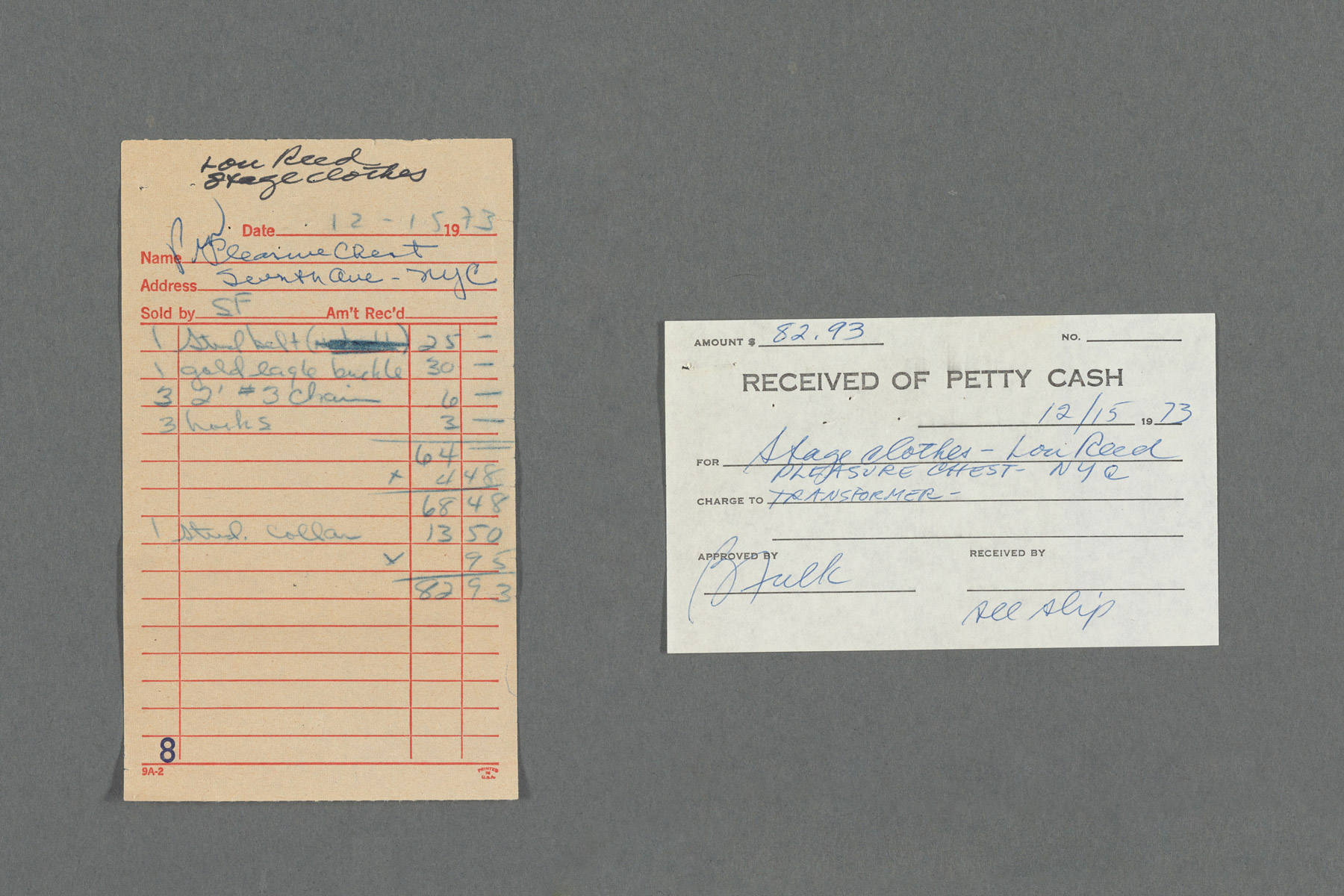

Petty Cash Receipts for Lou Reed’s stage clothes from The Pleasure Chest, NYC,

December 15, 1973

Lou Reed Papers, Music & Recorded Sound Division,

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Another dimension evident to everybody handling the materials was that the collection is primarily about Reed as a performing artist.

…it became clear pretty early on that this wasn’t a collection of Lou’s personal secrets and hidden diaries, which is what people always love to find. This is really in, in bulk, his business archive. This is the Sister Ray9 archive first and foremost, which is very powerful.

– Jonathan Hiam 10

…The archive contains much of the business papers that outline the transactions of the company. I would say that contained within the Lou Reed archive is a subset that one could think of as the archive of Sister Ray.

– Kevin Parks 11

It’s about his tours, it’s his business paperwork for decades of the tours and the studio sessions. And tapes to go along with that. Hundreds of hours of tapes of tours. It’s a fascinating look into that world. That’s what the Library saw value in.

– Don Fleming 12

It took three years following initial discussions with Anderson to make the collection available to researchers and patrons. A timeframe that Parks emphasizes “in library time, is super fast.”

One of Laurie’s explicit desires is that Reed’s collection be available on the web and widely distributed. I remember she had expressed real excitement when NYPL released the picture collection online with digital tools and user interface. It was basically the first time that the library’s digital infrastructure was built up enough to release tens of thousands of public domain images online. Doing that made a huge statement. It even made the front page of the New York Times arts section. So from the very beginning of the acquisition, of bringing in, of ingesting Lou Reed’s archive, there was the concept that it would be digitally accessible over the internet as much as possible.

– Jonathan Hiam 13

It’s the first NYPL music collection with a digital finding aid with active links on the library site directly taking library users to media playback of songs and video.

That may seem simple, but it’s a pretty big thing to pull off for a big institution. We needed to have the bulk of the materials digitized as soon as possible. We gave the estate the metadata and the organizational structures for these digitized materials. We let them choose engineers to work with, as long as they could fit the schema, which also allowed them to have the digital files on hand in their office, so they wouldn’t need to actually go to the library to retrieve any of their own materials if needed. When Laurie finally brought the materials to us they were ready to listen to and [to index] and catalog. It’s kind of a miracle that the collection really saw little or no friction at any point in its early life at the library.

– Jonathan Hiam 14

The American Society for American Archivists’ awarded The C.F.W. Coker Award to the library’s archiving unit for designing and implementing “a model for finding aids … setting standards of preserving a collection’s context in the digital realm… rigorously applying archival principles and standards in this large, multi-formatted collection that included audiovisual and born-digital materials…”

__________

The portrait of Lou Reed that emerged in the NYPL exhibition curated by Fleming with Jason Stern was drawn across several library collections including the manuscripts division. It started off chronicling the Velvet Underground and Songs for Drella (John Cale’s and Reed’s song cycle dedicated to Andy Warhol). By the time I stepped into “the library,” the exhibition’s third room, it dawned on me that Reed was a poet as much as a musician. Writing and New York City were central throughout his life.

In the library, there are letters from filmmaker Jonas Mekas, writers Hubert Selby and Vaclav Havel. Photos by Alan Ginsburg of Reed, photos of him with poet Jim Carroll, posters from his Saint Mark’s Poetry Project and other downtown venue readings and even a Thank You letter to Reed and Anderson for attending Havel’s state dinner at the Clinton White House.

Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars (installation shot)

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts,

Lincoln Center, New York

June 9, 2022 – March 4, 2023

Photo by Max Touhey, Courtesy of NYPL

We wanted to have a lot of the exhibition explained in his own voice and not us as the curators explaining it. [There’s] a quote about him talking about writing …. We used a quote from him talking about writing the lyrics to “Romeo Had Juliette” about how it took him months… every word had to fit just exactly right. We wanted to let him explain how he approached it as a poet.

– Don Fleming 15

__________

Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars (installation shot, detail)

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center, New York

June 9, 2022 – March 4, 2023

Photo by Max Touhey, Courtesy of NYPL

The largest part of the exhibition is devoted to Reed’s post-Velvet Underground music. Here he seems his most expansive, working with new collaborators and crossing back and forth between rock and roll, experiential music, theater, and film. On a raised platform in the center of the gallery are a flat screen and eight black and white video monitors playing abstract videos.

When we first found those open-reel, half-inch, black and white videotapes… we got some of them transferred. And the guy who did it said, ‘I’m sorry, but there’s something wrong with it. It’s just not working. The image is all fluttery, you can hear people talking, but they seem messed up. We couldn’t get it to stop.’ And then eventually we realized… Lou had done that on purpose. We found footage of him with… stacks of 50 TV monitors all set up on stage and they’re showing this footage. It was experimental film. Lou’s doing this on purpose.

During a sound check, there’s a person yelling from the back [telling] them to fix one of the monitors. It was Mick Rock. We recognized his voice immediately. He’s the photographer who took all the famous Lou shots as well as David Bowie and the rock band Queen. Before Mick passed away, he told us Lou had shot all this footage and he brought Mick along to run it. Mick’s job on tour was to take care of the TVs. They bought used TVs from a hospital. And they started breaking down at every show they did. Mick’s gig on the tour was to keep those background images going with the TVs.

– Don Fleming 16

Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars (installation shot)

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts,

Lincoln Center, New York

June 9, 2022 – March 4, 2023

Photo by Max Touhey, Courtesy of NYPL

Caught Between The Stars was less a library exhibition than a theater of memory.17 Anderson and the curators purposely designed it without a chronological timeline.

Laurie didn’t want the show to be in strict chronological order. And me, as an archivist, I think of everything in chronological order… but I came to appreciate [her thinking] …. We’ve got the Velvet Underground in the beginning, poetry in the middle, and then the solo big room. The other thing she said that was so useful to us is in one of the first mockups for that bigger room, it had more display cases against the walls with stuff above it. And she just said, “My neck hurts.” And we were like, “What?” And she said, “My neck hurts. I’ve just spent an hour going up and down, up and down, and when I’m done, my neck hurts.” We were like, okay, good comment. And that’s why the walls are just flat with images on them in that big room and the physical objects are layered in a framework of cases in the middle of the room.

–Don Fleming 18

__________

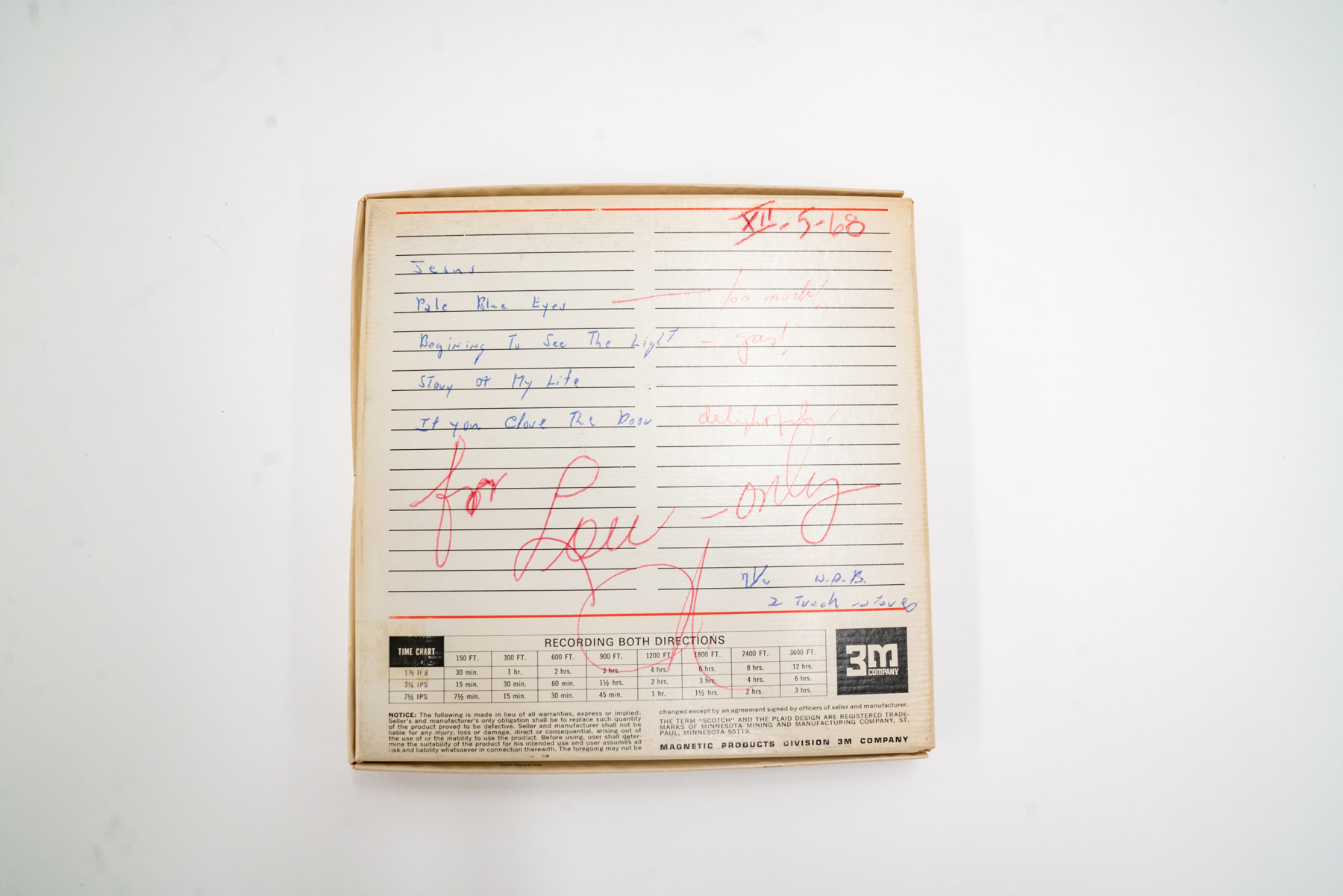

Perhaps one of the biggest surprises of the collection, its Holy Grail, is a 5-inch reel to reel tape Fleming, Jason Stern and Jim Cass discovered as they finished sorting through Lou Reed’s office.

It was in plain view the whole time. [We left] the Sister Ray office intact as long as we could… towards the end I was packing the last shelves up, putting all the CDs into a box and came across this one that was in this package. It wasn’t a CD, but it was the size of a CD. We had just always thought it’s some kind of deluxe version of something. Hadn’t really looked at it, but it was this package he had mailed to himself as a poor man’s copyright and then never opened. It still had the seal on. and my thought was, ‘Well, what’s inside this? Should I open it?’ But then something told me… let’s not open it yet. Let’s think this through a bit, because I could see the significance right away with the date on it. You could see through the wrapping that it was reel to reel tape. The Scotch [logo] came through a little bit.

Lou Reed demo tape, Postmarked May 11, 1965

from Lewis Reed to himself, Freeport, NY

1/4-inch open reel tape box and envelope

1965

Recorded by Lou Reed

Lou Reed Papers, Music & Recording Sound Division,

The New York Public Library of Performing Arts

We started researching it and we found out that same day he had been at Pickwick Records. And recorded a version of Heroin, what was thought to be the first version ever. And so we thought, well, it’s probably a copy of that. It’s the same date as that session. And then we didn’t open it for a couple of years. We didn’t open it until the library had acquired it. …And then when we opened it, it wasn’t that tape. It was in all likelihood made in the weeks prior to that on a home machine, not at the Pickwick studio, and had a set of songs that Lou was trying to [copyright], he starts every song saying, ‘Words and music, Lou Reed.’

– Don Fleming 19

The surprise and significance hearing that tape is lost on no one.

[That reel to reel tape] changes how we think of and look at Lou Reed… Acoustic guitar, harmonica, kind of… a Bob Dylan type thing. … Even his voice, it sounds like [Dylan] in parts, … he seems to even kind of imitate a little bit of the way folk singers, particularly Bob Dylan sang. We always think, oh, he hated this, you know, acoustic guitars and… he hated that whole folk revival … But that’s what [he] sounds like. – Kevin Parks 20

While a number of biographies document Reed and his college band playing Dylan songs, to actually hear this tape is a revelation. “I’m Waiting for the Man” and “Heroin,” two of the reel-to-reel songs, end up on the first Velvet Underground album with new arrangements.

I think what happened was they got their ears on a whole bunch of experimental stuff and John Cale was playing, sitting in with La Monte Young and all those people, and they decided, ‘Oh, let’s bring this kind of noisy element into it.’ The melodies are all the same. The chord changes are all more or less the same, but the songs are completely different when they finally appear on that first Velvet Underground record.

– Kevin Parks 20

__________

Almost all of Reed’s songs’ copyrights in his collection are owned by the recording companies that produced him, which brings up, of course, copyright and public usage. Reed’s music is available on site at the Library for Performing Arts. NYPL is very careful; however, to protect it from being distributed on the internet.

We try to make everything available inside the building. Nothing available outside of the building. We can get sued …People want us to protect their intellectual property. They want researchers to be able to have it. They don’t want it to be up on BitTorrent.21 And you know, as librarians, we want everything to be as free and as open as humanly possible, but at the same time, we know that, …it’s not ours to make free sometimes.

– Kevin Parks 22

Media archives in particular are resource intensive and traditional institutions are often hesitant to acquire them. When the New York Public Library accepts an archive, the institution allocates tremendous resources to preserve and store materials bequeathed to it on the shelves of the library or on the internet under the care of conservators and preservationists, far into the distant future. Lou Reed’s digital files, like others in the NYPL system are maintained on an array of storage systems distributed across the New York metropolitan area and other regions in the U.S. These systems are engineered to counter risk and the library has various software in operation to monitor the stability of each file.23

For something like this to be successful, Laurie trusted the library. A lot of it came down to Laurie trusted us. And that was a big part of it, because I can’t, I wouldn’t put myself in Laurie’s position when it is somebody’s partner, who’s handling their legacy. That’s a tough job for anyone. You want to do the best. You want it to be on the terms of the person you loved… And it does take a lot of trust. And I think in the end that was a big part of it.

– Jonathan Hiam 24

Laurie Anderson is the person who gave [Lou’s collection] to us. And she wanted all of it to be available to the people of the city of New York. The way Laurie handled it was perfect, and she did it exactly in the right way. It encourages research, it encourages people to listen to it.

– Kevin Parks 25

[The NYPL] is the place we’ve put the collection to be forever. [The library] should take care of it, theoretically, way beyond when we’re still here and at a certain point, it’s all public domain music. We won’t be here to see it, but hopefully at some point in the future, the library will determine that the copyrights have expired and can make it accessible beyond the library’s walls.

– Don Fleming 26

The acquisition of Lou Reed’s archive builds on years of innovation by NYPL to make their collections accessible to the public at the library and over the internet. The NYPL Reed Collection is another step in this evolution, conceived to be digital from its inception and searchable with web browsers. This endeavor coupled with the complexity of the Reed Collection’s diverse media required a new approach and workflow. This is not just a technical procedure, it’s truly a collaboration. The library worked closely with Anderson and her team on the process of formatting the materials and ingesting the media into their archives. Most of all, successful collaborative outcomes result from mutual trust and understanding. Thanks to NYPL’s and Anderson’s efforts, our knowledge and appreciation about Lou Reed as an artist, poet, and musician will only grow.

========

I would like to thank Don Fleming, Jonathan Hiam, Kevin Parks, and Alex Teplitzky, Communications Manager, New York Public Library for their time and interest in talking with me and answering follow up inquiries about the Lou Reed Archive.

1. “Everything Is Floating,” track 28, Laurie Anderson & Kronos Quartet, Landfall, Nonesuch Records, 2018, Nonesuch – 564164-2, compact disk

2. Jonathan Hiam, in discussion with the author, May 2023.

3. Kevin Parks, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

4. The Lou Reed Archive is the second largest in the NYPL music collection, followed by jazz producer George Avakian’s; conductor Arturo Toscanini’s Memorial Archive is the largest.

5. Don Fleming, in conversation with the author, March 2023.

6. Sisario, Ben, “‘You Don’t Become Lou Reed Overnight,’ A New Exhibition Proves It,” The New York Times, June 6, 2022

7. Jonathan Hiam, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

8. Kevin Parks, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

9. Sister Ray Enterprises is the name of Lou Reed’s publishing and touring company, also a Velvet Underground song from the White Light/White Heat album, 1968.

10. Jonathan Hiam, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

11. Kevin Parks in an email exchange with the author, July 2023.

12. Don Fleming, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

13. Jonathan Hiam, in discussion with the author, May 2023.

14. Jonathan Hiam, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

15. Don Fleming, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

16. Don Fleming, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

17. A memory system using physical space devised by the 16th century Italian architect and philosopher Giulio Camillo.

18. Don Fleming, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

19. Don Fleming, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

20. Kevin Parks, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

21. BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer file transfer protocol for sharing large amounts of data over the internet, in which each part of a file downloaded by a user is transferred to other users.

22. Kevin Parks, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

23. Alex Teplitzky, NYPL Senior Communications Manager in email with the author, July 2023.

24. Jonathan Hiam, in discussion with the author, May 2023.

25. Kevin Parks, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

26. Don Fleming, in discussion with the author, March 2023.

Main image

Lou Reed performing with Metal Machine Trio

at the Blender Theatre at Gramercy, New York, 2010

Photo by Amy-Beth McNeely

Image description

A photo of Lou Reed in his older age performing inside a dark indoors space. The photo captures Lou from the shoulders up, behind a performance controller or synthesizer that is not clearly visible. Lou wears round glasses and a black T-shirt and has dark curly hair. There is a microphone pointed at him to his left, although in the moment captured by the photograph, he is not singing into it.