Back in Time with Time-Based Works

Artists’ Books at Franklin Furnace, 1976-1980

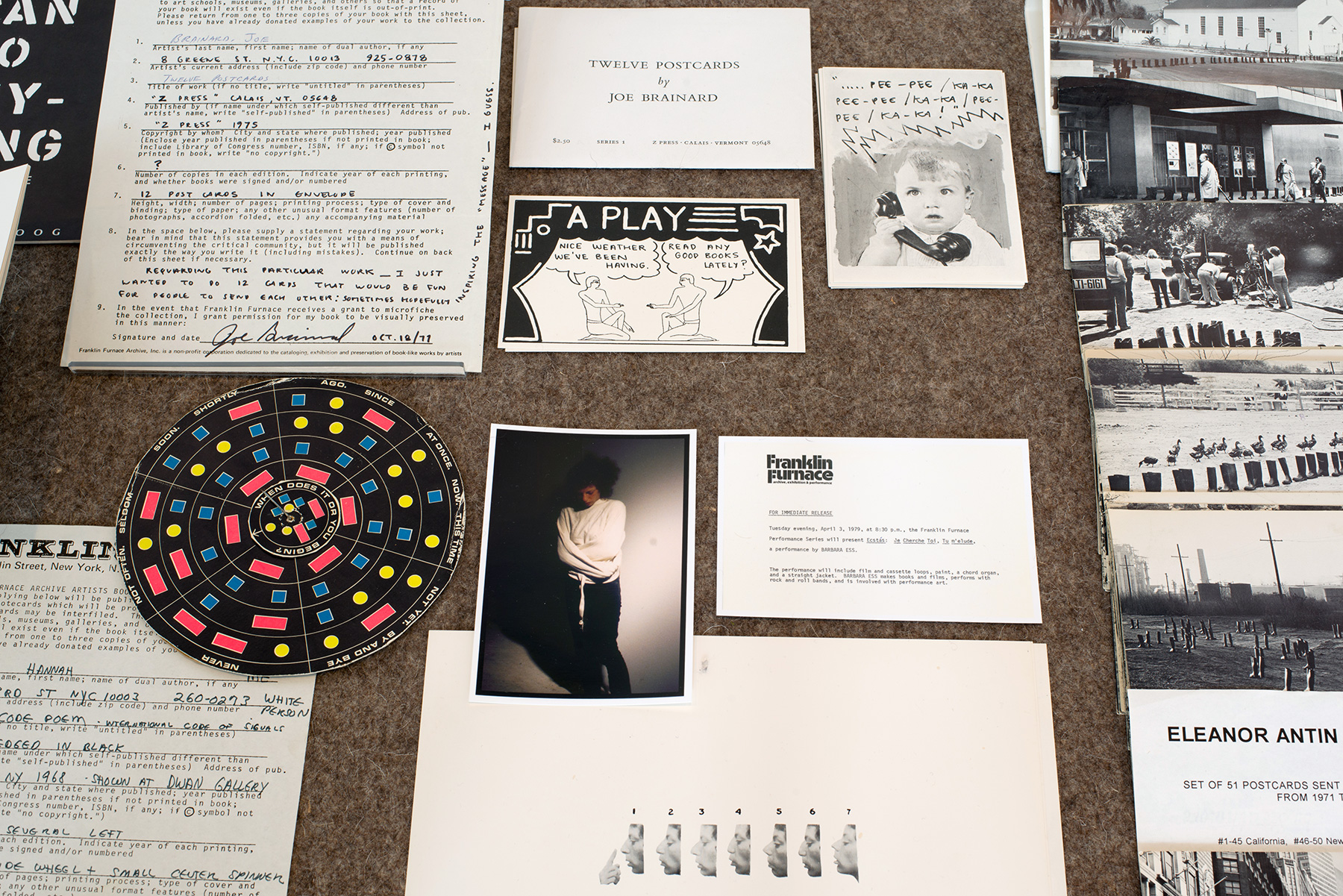

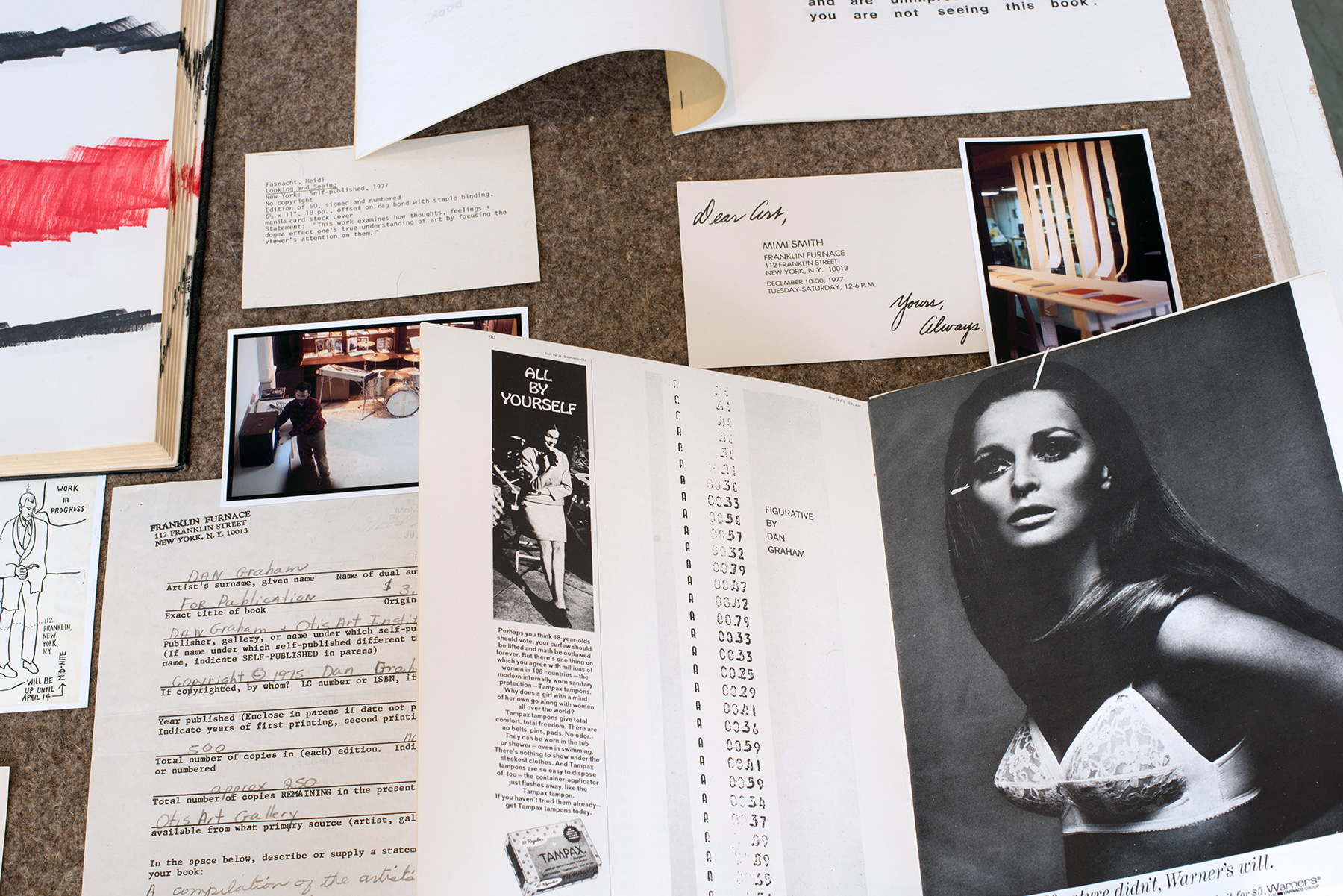

In the fall of 2016, the 40th anniversary of Franklin Furnace was celebrated with an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art organized by artist and Franklin Furnace founder Martha Wilson, Franklin Furnace archivist Michael Katchen, and myself. Back in Time with Time-Based Works: Artists’ Books at Franklin Furnace assembled historical photographs, correspondence, and printed matter from the first four years of the organization’s history, documenting its origins and early activities.

Selections from the artists’ books archive, which was acquired by the MoMA Library in 1993, traced the early development of the collection and the scope of works found in its holdings. The materials presented allowed for a historical view into the vibrant scene that Franklin Furnace created at its storefront loft in TriBeca as it worked to archive and exhibit new genres in contemporary art. The exhibition was also meant to promote the use of this collection at MoMA Library. The result of the independent labor of art workers during the run of Franklin Furnace’s archive is an incomparable historical view into artists’ experiments in publishing during the 1970s and 1980s. The following essay maps some of the context of the founding of Franklin Furnace and includes a set of reflections that Martha Wilson produced for the show thereby providing a first-hand account of the early days of the artist-run space.

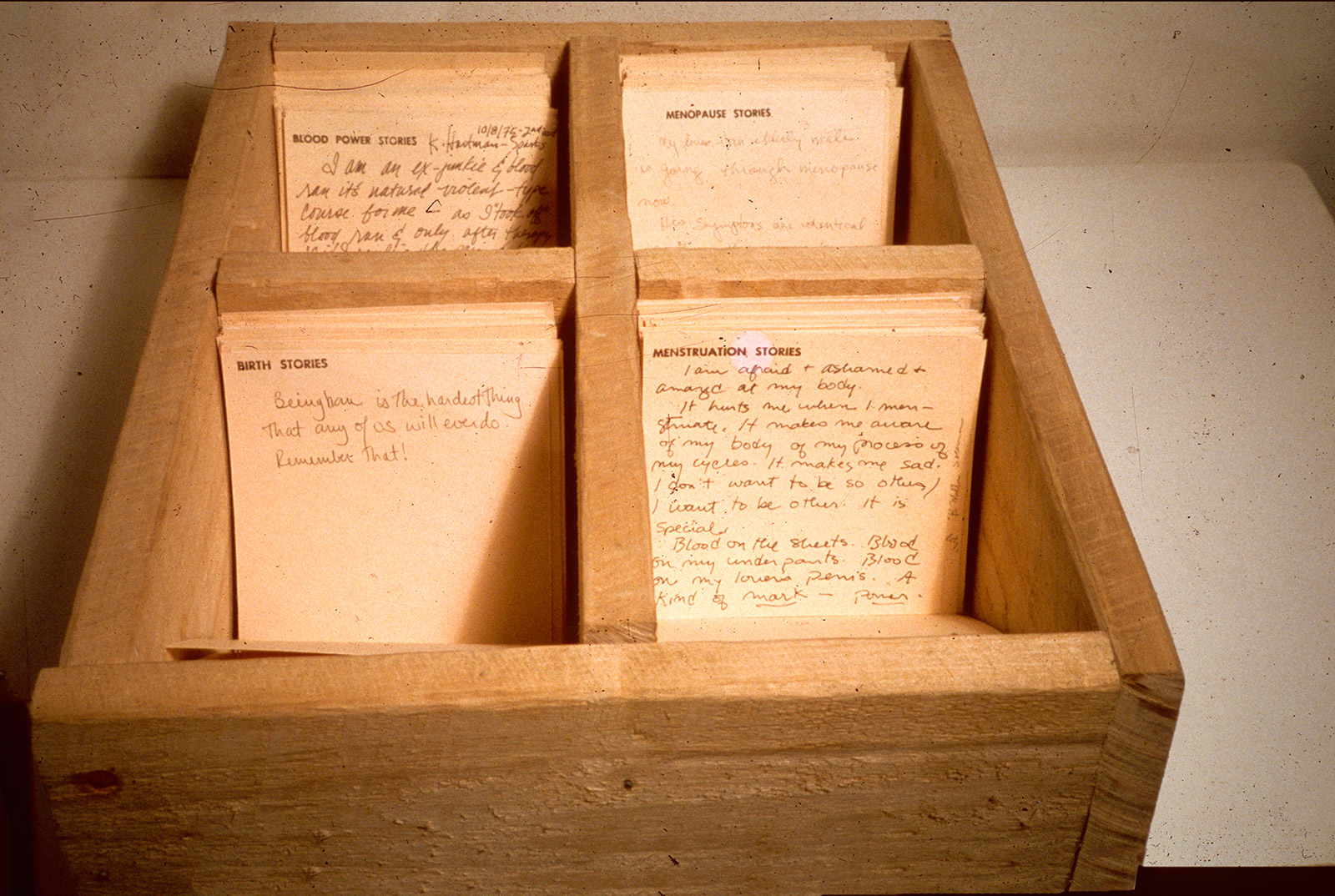

Artists’ relationships to publishing and the distribution of printed matter took a conceptual turn in the 1960s. Self-publishing and using the format of a book or journal as a container for new ideas were strategies artists seized upon for connecting more directly with audiences and for allowing experimental projects to be transported globally through the mail via small books, magazines, and ephemera. Artists’ publications facilitated alternative networks of discourse and exchange of ideas, and several artist-run organizations founded in the mid-1970s focused on the promotion and critical reflection of this medium. In many ways, it aligned with other new media practices, like the nascent video art scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s. There was a critical significance to decentralizing the production and distribution of media – in both print and in moving-image production – through activities like cable-access channels and independent video collectives. The underlining radical edge to this type of artistic production reflected some of the language and organizing tendencies of collective groups gleaned from protest movements also happening at that time.

Installation view of Back in Time with Time-Based Works: Artists’ Books at Franklin Furnace, 1976–1980, 2016

Photo: Michael Katchen

Several important hubs for the distribution of artists’ books and related materials popped up around world, fostering a network that linked individual artists and collectives. For example, the artist collective General Idea founded a bookstore and archive called Art Metropole in 1975 for artists’ publications and multiples in Toronto. Also in 1975, Ulises Carrion started a bookstore (later turned archive), Other Books and So, in Amsterdam, which served as an important European node in this artists’ book network. In New York, two important organizations bubbled up around this same time: Franklin Furnace and Printed Matter. Printed Matter was founded in 1976 by a collective of artists and art workers that included Lucy Lippard, Sol LeWitt, Edit DeAk, Pat Steir and Walter Robinson, among others. The focus of the organization at its founding was to develop a reliable distribution system for books made by artists.

Martha Wilson arrived in New York from Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1974, having encountered the experimental publishing program at Nova Scotia School of Art and Design. NSCAD flourished for a period as an international center for conceptual art experiments within the framework of their visiting artist program as well as NSCAD Press, run by Kasper Koenig which specialized in publishing primary documents and artists’ writings. Wilson published a few books on her own, and, also around this time, was included in Lucy Lippard’s important c. 7,500 exhibition of conceptual art by women that originated at CalArts and traveled to various venues across the US in 1972-73.1

When Wilson founded Franklin Furnace in 1976, it was as a bookstore for artists’ publications, with similar intentions to the collective that formed around the idea of Printed Matter. There was a dearth of venues for artist-publishers to sell their books in New York, and Franklin Furnace was meant to fill this void. However, the two organizations quickly recognized the redundancy of their respective intentions and missions, which led to an interesting agreement: it was decided that Franklin Furnace would become an archive and meeting space for artists’ publications and Printed Matter would continue on as the distributor and commercial venue for the sales and promotion of these books. This agreement clearly set the agendas of the two organizations. Franklin Furnace transformed into an independent archive and quickly became the leading repository for experimental publications by contemporary artists. In addition to the book archive, Franklin Furnace ran an active exhibition and performance program, providing a space for artists who were experimenting with publishing to perform or exhibit their work through readings and installations.

The early history of Franklin Furnace was part of a broader scenario where downtown New York was animated by venues for new art, music, film, and performance. These alternative spaces often occupied vacant industrial or other disused buildings, and created new environments for artists and performers to experiment and collaborate. As artist and curator Howardena Pindell recognized, publications themselves created spaces in which artists could experiment with new forms and disseminate critical dialogue on their own terms.2 Franklin Furnace, established directly in the context of other alternative spaces in downtown New York, reacted to this movement of artists’ books by providing a space for exhibiting the medium and fostering connections amongst an international community of thousands of artists-publishers.

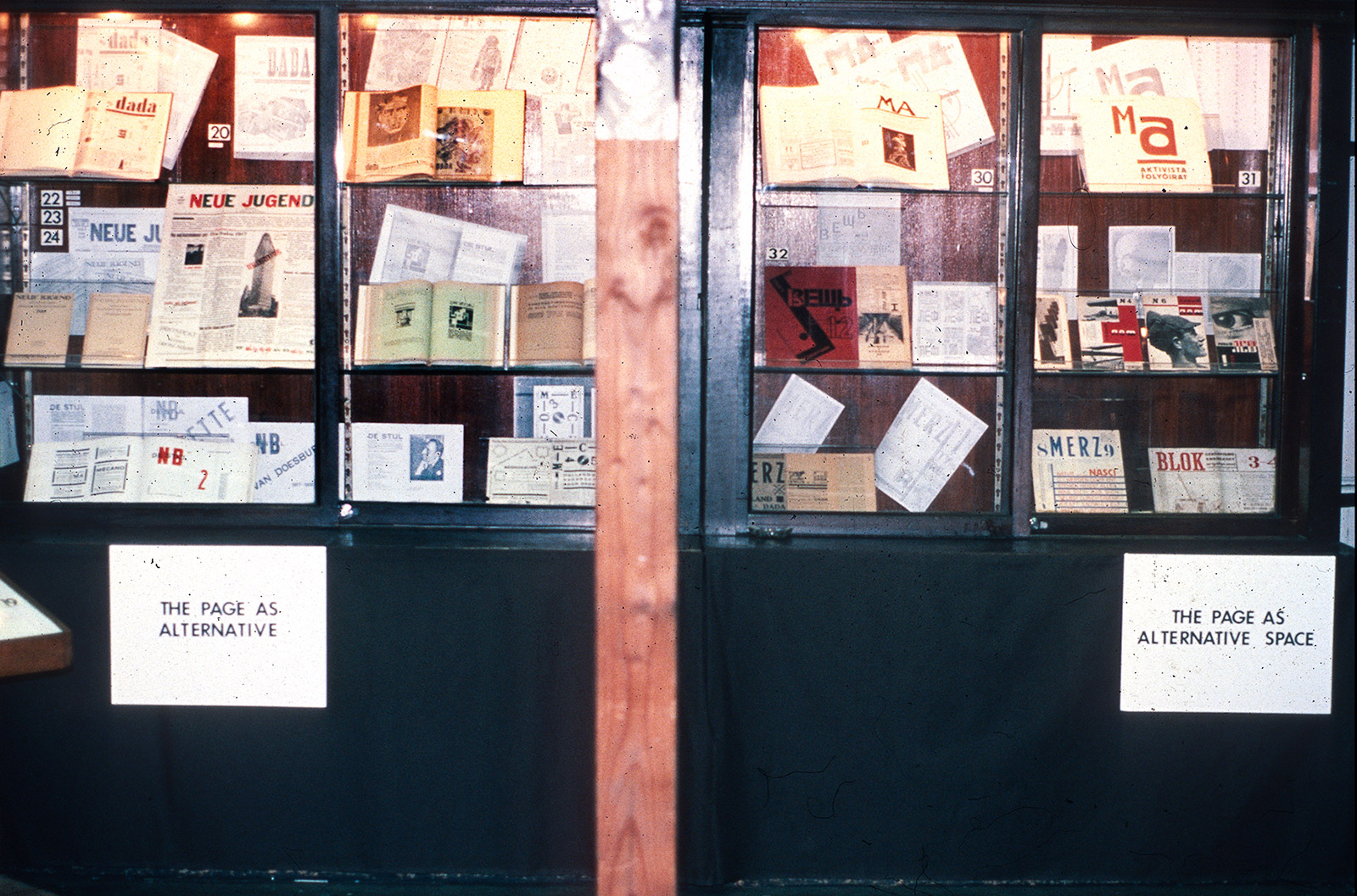

This correlation was further explored in a series of four exhibitions that took place at Franklin Furnace in 1980-81, collectively entitled, “The Page as Alternative Space.” Taking inspiration from Pindell’s essay, Martha Wilson invited specialists in the field to organize different iterations of the show. The documentation of these projects, including checklists, invitations cards, and installation photographs, formed the end-point for our recent exhibition at MoMA. Then-MoMA Library Director, Clive Phillpot curated the first show with a chronology from 1909-29, which included a selection of magazines and books from the historical avant-garde. Charles Henri Ford, artist, publisher and editor of the important American Surrealist journal View, organized the second show, which had a chronological range from 1930-1949. Jon Hendricks and Barbara Moore, who ran the bookshop Backworks, covered the period from 1950-1969. Their show featured a mixture of artists’ magazines and books from early conceptual artists and Fluxus artists as well as political-engaged newspapers, printed manifestos and posters from the time period. Ingrid Sischy, then editor at Artforum, and curator Richard Flood were given the task of covering the most contemporary examples of artists’ publishing from 1970-1980. The historical materials in the first three shows developed a critical lineage which one could then relate or contrast to the tendencies of the contemporary moment. This was a fairly unprecedented attempt to curate a legible narrative and to conjure a critical language for the genre. The last section included books by artists such as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Martha Wilson, Constance Dejong, Laurie Anderson and Kathy Acker. It explored various approaches to text-based works and the use of language and information as visual media, often positioning reading and the performance of texts as part of a work.

In the archive of Franklin Furnace, we find early printed works from a wide range of artists, some now very-well known, at a moment in their career when they were experimenting and trying to find their voice. Our survey of the collection of books acquired during the first years of Franklin Furnace conveys this “on-the-ground” archiving of the artists’ scenes in New York. Wilson and her colleagues at Franklin Furnace were closely embedded within a community of artists in New York and abroad, and these connections and friendships created unique access to materials. Research for the show in the ephemera files and exhibitions correspondence made this point completely apparent. As word of the archive spread, the archive had a more global reach, attracting donations of books and announcements from a diverse international group of artists/publishers from Europe, South America and Asia.

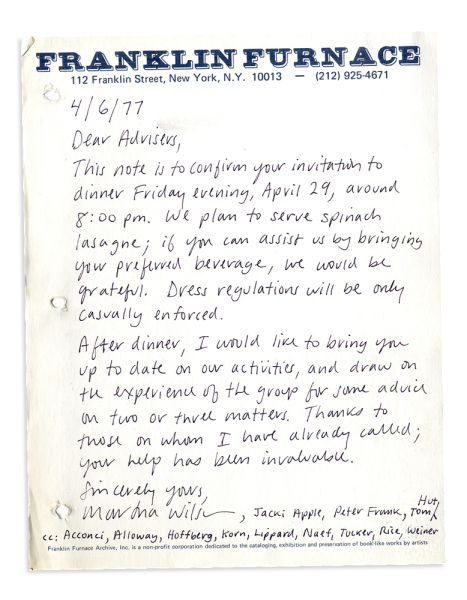

In this way, the archive simultaneously promoted and fostered a network of distribution in the moment as well as preserving the content of this artist movement for future researchers. As part of the process of donating books to the Franklin Furnace collection, artists and publishers were asked to complete submission forms, which included basic bibliographic information like author, title, date of publication, and publisher. The forms also included space for artists to provide a statement. In some cases, artists chose to leave this field blank; in others, they provided a statement that gives direct insight into the spirit and intention of the work. In the exhibition, these submission forms were shown alongside the publications they described, allowing for the voices of the artists to come through. Often written by hand, the forms are evocative documents that clearly trace the history of the publications, and provided the information used in the Franklin Furnace Archive Artists’ Book Bibliography that Franklin Furnace published in three volumes between 1977 and 1979. In that same spirit, we also produced a pamphlet for the MoMA exhibition with some direct reflections on the founding of Franklin Furnace by Martha Wilson. She was able to cover some of the ideas and motivations for the founding of Franklin Furnace. Following are quotes in her definitive voice on the subject organized into four brief sections.

Conceiving and organizing Franklin Furnace: I visited New York in 1970 because Kynaston McShine had included my boyfriend, Richards Jarden’s artwork in the Museum of Modern Art’s Information show. We were living in Halifax, Nova Scotia where he was getting a MFA at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design while I was getting a MA in English Literature at Dalhousie University. We drove 21 hours to New York and saw, through the works in the Information show, that text could function as image; that performance could be documented by text; and that image and text could convey concept. HALLELUJA!

After I moved to New York in 1974, I went to MoMA to ask the bookstore to sell my artists’ book. The manager of the bookstore declined my request, saying, “Look lady, the book costs $5 but it would cost me $5 to do the bookkeeping.” Regular bookstores said my work was not a book in any case. The Whitney started an artists’ publishing program—but for high-end projects that regular people could not afford. So I decided to open a bookstore for artists’ books in my TriBeCa living loft, which because it had been a ship chandlery, contained display cases.

Lots of artists were self-publishing their work, but it seemed that no established institutions were paying close attention to the phenomenon. Bookstores like Jaap Rietman and Wittenborn sold some artists’ books, but nobody was collecting and conserving artists’ published work. Apparently, this material was not perceived as art, or at least not valuable art, so why include it in art history? Well, I could see there was a vacuum that needed to be filled, and that if I got my act together before my unemployment insurance ran out, I could support myself while providing a service to the art world.

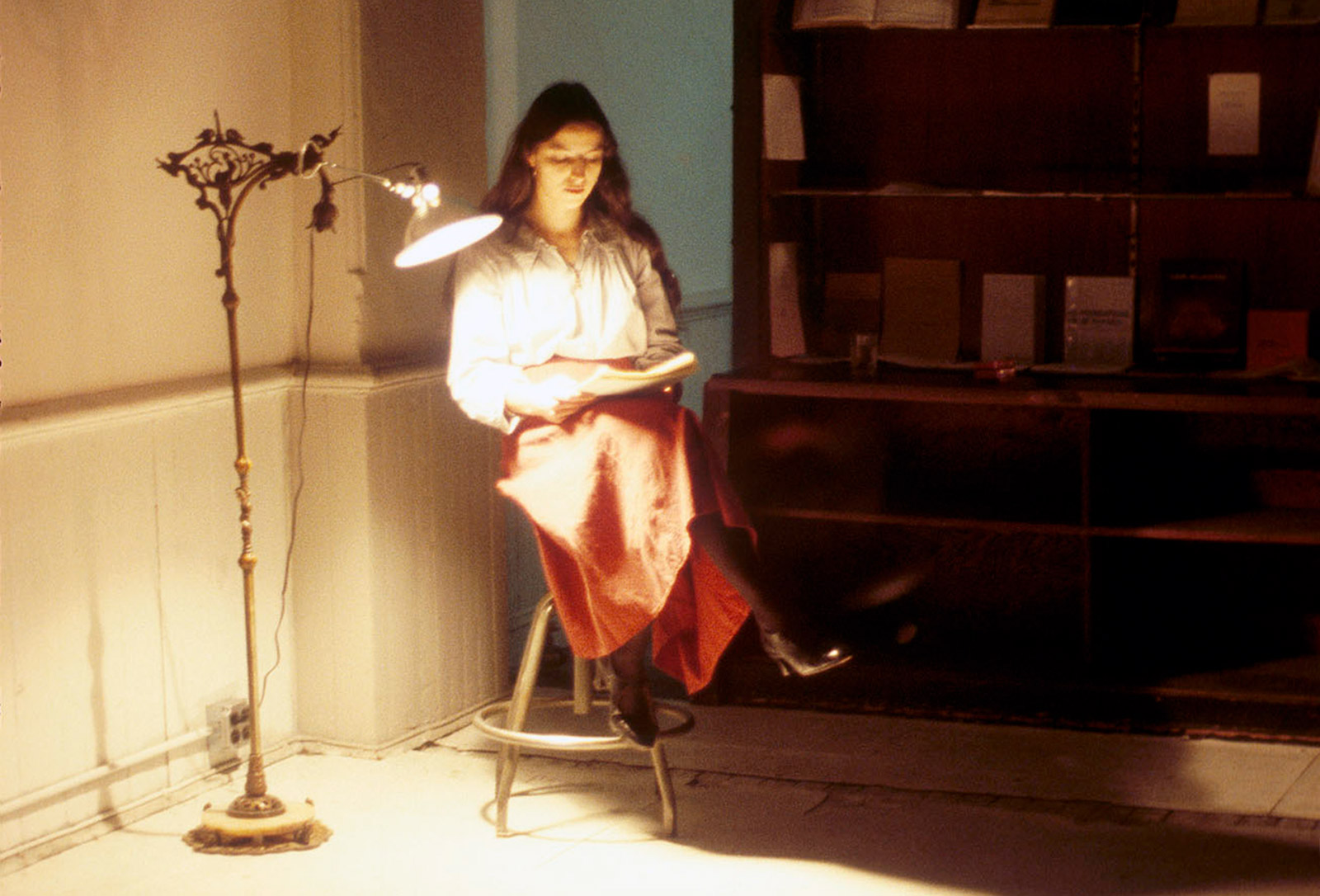

Installation photograph for Dara Birnbaum, (Reading) Versus (Reading Into), 1978

Photo: Michael Katchen, courtesy of Franklin Furnace

112 Franklin Street: The mid-1970s were a very busy time in and around Lower Manhattan; I thought if I had 10 friends who were making artists’ books, there must be at least 30 more artists who were also creating and publishing artists’ books. By opening day on April 3, 1976, I had received 150 titles; and by the time Franklin Furnace sold its collection to the Museum of Modern Art in 1993 it was the largest artists’ books collection published internationally after 1960 in the United States.

Willoughby Sharp, publisher of AVALANCHE magazine, wanted to create an art center, the Franklin Street Arts Center, with each floor serving a different aspect of contemporary art-making, including a bookstore on the 1st floor, radio station on the 2nd, film production on the 3rd, video production on the 4th, and a theater on the 5th. But everybody just bought a hot-water heater and started living; and by the spring of 1976 I had been in enough building meetings with Willoughby to figure out that his MO was to yell until everyone gave up. I decided to incorporate Franklin Furnace as a separate not-for-profit organization. But giving credit where credit is due, the name, “Franklin Furnace,” is Willoughby’s coin; I was going to call my store the Franklin Stove, but Willoughby insisted, “No, you must call it Franklin Furnace!” And the name stuck.

While this was going on, Printed Matter was being formed by a bunch of artists and activists including Edit DeAk, Sol LeWitt, Irina von Zahn, Lucy Lippard, Pat Steir, Robin White, Mike (later Walter) Robinson, Mimi Wheeler, with the goal of distributing artists’ books.

There was the question of space. I had a storefront already, Printed Matter wanted one, so we started discussing collaboration in the same space. When Willoughby got wind of this, he and his lawyer, Bob Projansky, came downstairs to yell, “THIS WILL NEVER BE KNOWN AS THE PRINTED MATTER BUILDING!” His outburst had the desired effect of turning off Printed Matter; they subsequently found a storefront on Lispenard Street, and we agreed to divide the pie into Printed Matter’s for-profit half of publishing and distribution, and Franklin Furnace’s not-for-profit half of exhibition and archiving. (About 10 years later, Ingrid Sischy, then-director of Printed Matter, made the case to the IRS that the organization had never made a profit and not-for-profit status was awarded.)

Artists’ Books: Because there was no agreement as to the form artists’ books could take, I was calling them “book-like works by artists.” This did nothing to describe works in accordion shapes, works that unfolded in four directions, or were contained in cookie tins. What should we do about the different impulses represented by published and one-of-a-kind works?

As Lucy Lippard wrote in the 1976 issue of Art-Rite magazine devoted to artists’ books, “One of the reasons artists’ books are important to me is their value as a means of spreading information—content, not just esthetics. In particular, they open up a way for women artists to get their work out without depending on the undependable museum and gallery system (still especially undependable for women). They also serve as an inexpensive vehicle for feminist ideas. I’m talking about communication but I guess I’m also talking about propaganda. Artists’ books spread the word—whatever that word may be. So far the content of most of them hasn’t caught up to the accessibility of the form. The next step is to get the books out into the supermarkets, where they’ll be browsed by women who wouldn’t darken the door of Printed Matter or read Heresies and usually have to depend on Hallmark for their gifts. I have this vision of feminist artists’ books in school libraries (or being passed around under the desks), in hairdressers, in gynecologists’ waiting rooms, in Girl Scout Cookies…”

A few years in, there was still some needs that I felt the major institutions were not accommodating: One was major exhibitions devoted to the history of artists’ publishing; and the other was publications which documented what was going on in the field of artists’ books. I decided to invite four sets of guest curators to survey artists’ publishing during the 20th century, and to prepare selections for a year-long exhibition entitled The Page as Alternative Space. Clive Phillpot was the curator of the first section, from 1909 to 1929; Charles Henri Ford took 1930 to 1949; Barbara Moore and John Hendricks 1950-60, and Ingrid Sischy and Richard Flood, 1970-80. Franklin Furnace did not own any of the works that were exhibited; we borrowed works from institutions and collectors, inaugurating our museum function with this show.

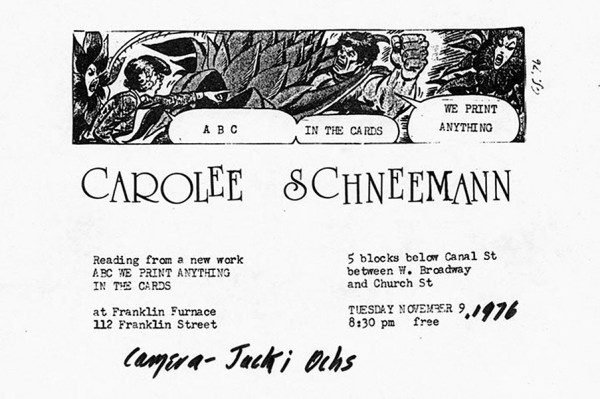

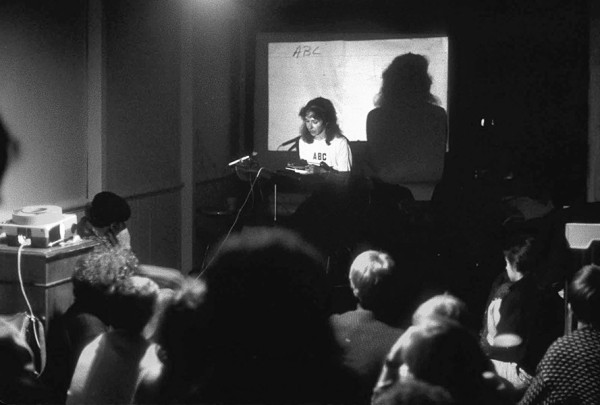

Performance Art: When I founded Franklin Furnace in 1976, I invited artists to read to the public. Every single artist I invited to read chose to manipulate the performative elements of light, sound, relationship to the audience, props, costume and time as part and parcel of the work. (The misnomer “performance art” had not taken hold as yet.) The word in vogue at the time was “piece,” which encompassed the thought, the action, the documentation—drawn or photographed or filmed or published or taped—whatever.

Announcement, Carolee Schneemann reading event for “ABC We Print Anything,” 1976

Courtesy of Franklin Furnace

Carolee Schneeman performing in reading event for “ABC We Print Anything,”1976

Courtesy of Franklin Furnace

The doors of Franklin Furnace had been open for three months when artist Jacki Apple, volunteer curator, suggested Martine Aballéa, an artist in the collection, read from her book. She showed up in costume and the performance art program of Franklin Furnace was born.

Martine Aballéa performance at Franklin Furnace, 1976

Photo: Michael Katchen, courtesy of Franklin Furnace

Soon Jacki started curating Window Works that broadcast artists’ ideas to passers-by on Franklin Street; and inviting guest curators to organize thematic exhibitions in the display cases. So within the first year, Franklin Furnace’s public exhibition programs were established. Jacki also realized we weren’t going to make any money if we didn’t publicize what we were doing better. She got a press list together and started writing Press Releases for our events.

I’ve worked with the books and ephemera from Franklin Furnace’s archive at MoMA Library for over a decade now, and I continue to be impressed by the labor and energy of the art workers that collected and managed this archive. Its creation expanded demands on the staff, in terms of cataloging and housing the materials, and as Martha Wilson has told me, they were aware that the preservation concerns for over ten thousand artists’ books in her downtown artist-run space really would eventually exceed the capabilities of the organization and the physical structure of their building. By the time MoMA acquired the entire Franklin Furnace Archive in 1993, there were roughly 8,000 titles in the collection, and it took several years for the books to be cataloged in our system and folded into the existing artists’ books collection at MoMA Library. The titles are now at the core of our artists’ books collection and play a decisive role in how we can trace a history of artists’ books in contemporary art.

Franklin Furnace still exists as a non-profit arts organization. They have had several different incarnations since the 1990s, though now they run an active grant-giving program for performance artists out of Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. They also maintain their own archive, specifically the rich documentation of performance activities at Franklin Furnace. The show at MoMA was a great chance to collaborate with Martha Wilson and Michael Katchen, who are both still a part of Franklin Furnace, to learn more about the archive and to publically celebrate the 40th anniversary of this unique archive of artists’ books.

1c.7,500 was the last of Lucy Lippard’s “numbers” shows, and the “7,500” in the title represented the population of Valencia, California, where the show debuted before touring the US and to London. The show was an all-women show of conceptual art that included Adrian Piper, Bernadette Mayer, Christine Koslov, Alice Aycock, Nancy Holt, Eleanor Antin, Agnes Denes, Alice Aycock and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, among others. The catalogues for the “Numbers” shows by Lippard were notable for their format of being printed on loose notecards that resembled a library card catalog.

2Howardena Pindell, “Alternative Space: Artists’ Periodicals,” The Print Collectors Newsletter 8, no. 4 (Sept-Oct 1977).

Further Reading

Franklin Furnace, Franklin Furnace Archive Artists Book Bibliography (New York: Franklin Furnace Archive, 1977-1979).

Clive Phillpot, “Convergence: The Furnace and MoMA,” TDR (1988-) 49, no. 1 (2005): 94-103 (http://www.jstor.org/stable/4488623).

Toni Sant, Franklin Furnace & the Spirit of the Avant-Garde: A History of the Future (Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2014).

Martha Wilson, interview by Lynda Browner, Art Spaces Archive Project, June 4, 2010 (http://www.as-ap.org/oralhistories/interviews/interview-martha-wilson-founding-director-franklin-furnace).

Martha Wilson, Martha Wilson Sourcebook: 40 Years of Reconsidering Performance, Feminism, Alternative Spaces (New York: Independent Curators International, 2011).

https://vimeo.com/franklinfurnace/videos

Main image

Installation view of Back in Time with Time-Based Works:

Artists’ Books at Franklin Furnace, 1976–1980, 2016

Photo: Michael Katchen