Art For the Public’s Space

The Oakland Museum’s Chalkboard

Amidst a busy day of multi-generational programming at the Oakland Museum of California’s 24th annual Lunar New Year Celebration in February 2025, museum staff and San Francisco based painter and muralist Chelsea Ryoko Wong unveiled a new work titled Calling Home in the museum’s main entrance area, Oak Street Plaza.

With its terraced slab roofs, an outdoor garden, roof garden, lounge areas and gallery entrances directly off the Plaza, the location of Calling Home [Figure 1] is multifunctional. With its emphasis on art and nature, and functioning as an extension of the urban space, the setting provides an experience opposite that of the typical museum façade. Anchoring Ryoko Wong’s 36 x 20 foot mural are depictions of five architectural structures of differing styles. Ryoko Wong simulates a lively night scene on a street in Chinatown. As opposed to being a backdrop, the architecture in Ryoko Wong’s composition is portrayed as a space with which the various figures in cultural and modern attire actively engage. Weaving through the mural, figures – some in traditional dress and others in colorful patterns – are shown shopping, performing, caring for family members, and gathering. A string of lantern lights loops across the composition. At the bottom of the piece, Ryoko Wong added a cluster of the city’s famous Black Crowned Night Herons.

Open during museum hours, Oak Street Plaza is a free public space. Temporary murals commissioned by local artists rotate twice a year on the wall called “the Chalkboard.” Different curatorial teams (each with representatives from Curatorial, Production, Collections and Conservation, Learning and Engagement departments) identify and commission artists in conjunction with temporary exhibitions. The content is distinct from exhibition content. Past murals include Jet Martinez’s 2017 Resilience [Figure 2] which featured large flowers and Monarch butterflies, and was installed in conjunction with the exhibition Metamorphosis & Migration: Days of the Dead. The artist explained, “This mural celebrates the Zempasuchil (marigold), a symbol of the fragility of life, and the Monarch Butterfly, a symbol of trans-generational migration.”1 Shortly after the mural was installed, the Plaza was used as a performance and community programming space during the museum’s annual Día de Muertos celebration. At other times, murals have been produced in collaboration with external organizations, such as the project “For Freedoms.” For that project, artist Chris Johnson invited public responses to the question “Do you have faith?” through the collaborative installation A Question of Faith [Figure 3] in the months before the 2018 election.

The question presented on the Chalkboard functioned in dialogue with a billboard on OMCA’s exterior wall by the arts and civics organization For Freedoms that featured a 1930s era photograph by Dorothea Lange and the words of American Transcendentalist Theodore Parker: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”2 The choice of Lange is significant to OMCA, which holds the influential documentarian’s archive. For Freedoms developed nine other billboards with the same quote and different Lange Photographs, and mounted them around Oakland. Meanwhile, the Chalkboard functioned as the public’s space for direct and personal engagement. At various times during the installation, the museum hosted workshops in Plaza related to the role of faith and history in politics, and of artists in civic dialogue.

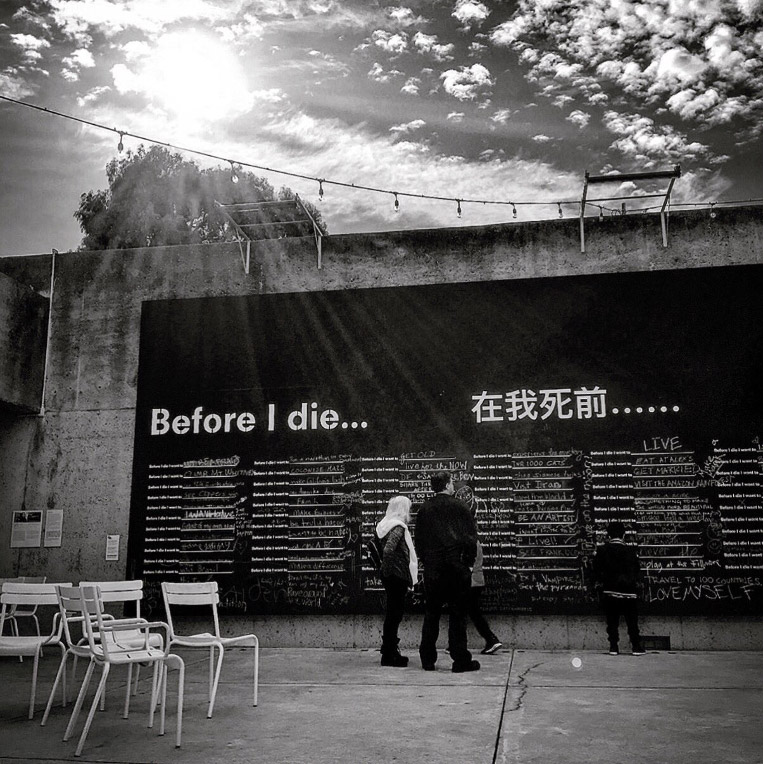

“Chalkboard” captures both the ephemeral nature and timely content that is featured there. Though it literally began as an open black wall for use by the public, today the Chalkboard alternates between being used as a space for the display of local contemporary art and as a large “chalkboard” where the museum coordinates opportunities for the public to collectively rest, or to experience programming, or explore and respond to contemporary issues through community engagement activities. When staff decide, it’s also just been a blank space for the public to take a piece of chalk and share words like “Love makes America great”, as someone wrote in January 2017. For a 2019 installation, artist Candy Chang asked the public for their bucket lists through a prompt “Before I die…”[Figure 4]. Artists who create murals for the Chalkboard participate in an active and evolving public visual and experiential exchange of picture, words, and community expression. Grounded in the Oakland Museum’s history, the Oak Street Plaza includes permanent outdoor art by artists including collection objects Ruth Asawa and Viola Frey.

Many of the objects that comprise the Oakland Museum’s interdisciplinary collection of over two million artworks relate to the kind of everyday life and experiences reflected in Calling Home. For example, the renowned All of Us or None collection of political posters traces the emergence in the 1960s and the unique history of this ephemeral form in the Bay Area. Many of the posters in the collection even reproduce famous historical Bay Area murals. There is a thriving history of murals as a public art form in the region with Diego Rivera’s Pan Pacific Unity for the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1940 helping to drive this interest. Ryoko Wong created Calling Home as a reflection of her time spent as an artist in residence at the museum during which she performed research in the community and in the museum collection, and engaged in programming. Jet Martinez’s inspiration was different: Jet’s painting style for the mural takes inspiration from painted enameled plates originating from Michoacán, Mexico, which is also, as the artist notes, where many Monarchs culminate their journey.

Following the OMCA building design of architect and Pritzker Prize Laureate Kevin Roche (1922-2019), the Chalkboard murals extend the mission of Roche’s building design to dissolve the boundaries between the museum and public spaces, with an emphasis on the public. Roche originally conceived the building as an integrated complex of art, history, and natural sciences galleries and an urban park. The three-tier terraced design by Roche with gardens designed by landscape architect Dan Kiley (1912-2004) function as extended outdoor galleries, with each gallery roof serving as the terrace for another.

Since the founding of the Oakland Museum in 1969, its curators have been inspired by how Roche’s design integrates the museum into the civic and natural environment. Roche once explained: “The most important thing one can achieve in any building is to get people to communicate with each other. That’s really essential to our lives. We are not just individuals—we are part of a community.”3 Moreover, Roche believed in the work of the architect as a service to the community: “We’re in service to the people in the community that we are building for. You have to understand them. It’s very, very real. Your role is to serve the community. You have no other role but to serve.”4 Located in Alameda County, Oakland is a working-class city in the Bay Area’s most diverse county.

Calling Home is the one of the pieces Ryoko Wong’s presented following her experience as an artist in residence and a larger exhibition presented in the nearby Gallery of California Art, titled Ancestral Visions. For this commission, Ryoko Wong had access to the museum’s collection of textiles, specifically textiles from the Chinese American community. Her paintings are inspired by early twentieth century dresses in the museum’s textile collection owned by half a dozen Chinese women: Rose Setzo, Sophia Chang Wong, Grace Dea, Lei Kim Lim, Chop Chin Chum, and Sun Fung Lee Wong. Developed over the course of a year, the gallery-based portion of Ancestral Visions includes five large paintings along with the actual dresses on hangers presented on a descending rail that recall that of a dry cleaner. Ryoko Wong’s project is especially meaningful to the museum’s location in Oakland’s Chinatown, one of the oldest Chinatowns in the United States. While Oakland’s Chinatown was settled in the 1850s, the current location is not its original one and its residents and businesses once again face displacement. The themes of women’s labor, tradition, friendship, community, and everyday life are themes in the paintings and in the mural installed in the plaza. While the paintings represent the lives of the real women who owned the dresses, the mural broadly portrays aspects of the Chinatown community to which they belonged. Visitors can move fluidly from the street to the Plaza without having to go through a paywall.

Today, the Chalkboard is just one of several spaces the museum uses for public art around the Oak Street entrance. From the street, visitors can view other sculptures punctuating the skyline from spaces atop the museum. Across from the Ryoko Wong mural, an early wire sculpture on the facade by Ruth Asawa (the Oakland Museum was the first museum to acquire works by Asawa) hangs surrounded by a small cactus garden [Figure 5]. Installed across the street from the museum on the Oak Street Overpass is Henry Rollins’ 39-foot steel sculpture, Anansi (1969-1974) [Figure 6]. In this way, the Chalkboard artworks function in dialogue with a cultural legacy of Bay Area artists committed to connections between art, community, and social uplift. Rollins’ Anansi is situated between apartment complexes. Close to the museum but also distinctly apart from it, the piece provides a vision for how museums can straddle the worlds of their campus and beyond. Towering above the overpass, the symbolism of using knowledge and internal strength to overcome challenges resonates with a city that has long struggled with various fiscal and social impediments. Meanwhile, Ruth Asawa was a pioneering proponent of the power of art in everyday life. The “public” – encompassing the natural environment, the built environment, and its inhabitants and their histories – were essential to her work. Her simple materials and nature-inspired pieces are accessible to a range of audiences.

As the visitor approaches the museum campus, they are welcomed by public art and by programming that announces and demonstrates an intention to decenter the focus on the museum as the producer and owner of space and the collections it stewards and the stories it presents. One visitor, Jeffrey Inscho, described just such an experience:

As I entered the museum from the Oakland Street courtyard entrance, I was struck with the first thing I saw: a large outdoor community gathering place situated before you even reached the ticket counter where several dozen people were hanging out in the Northern California sun. There was a very large chalkboard on one of the exterior walls upon which visitors could leave their mark. This struck me as very different. I visit a lot of museums and can’t recall one inviting this kind of open engagement with visitors before they’ve even entered the building. This space instantly set the tone that the museum belonged to the community, and was there to serve the community.5

Rollins and Asawa are associated with an exhibition that opened a new era for public art at Oakland Museum that brought the public, the museum, its community and audiences together in new ways, the 1974 exhibition titled Public Sculpture/Urban Environment. ART, the Oakland Museum’s publication, described the exhibition “as important for the museum as for the community.”6 Siting pieces both on the museum’s 7-acre campus and around Oakland’s downtown, and “putting the artist with the daily environment, we hope to stimulate new awareness and interest that will not only benefit the citizens of Oakland but the bay Area art community as well.” Curator George C. Neubert sought to create a different conception of how a museum and public art could engage with the public sphere. Neubert explained that the exhibition “expands contemporary aesthetics beyond the museum wall and puts art within the context of a daily environment in hopes of stimulating new interest and awareness that will benefit not only the Bay Area art community by the future of Oakland as a vital creative environment.”7

The ethos of the Public Sculpture exhibition lives on today through the Chalkboard, which was formally identified as a public interactive audience driven space in 2012. It started out as Chairs of the Board a design by Mark Jensen Architects [Figure 7]. Metal garden chairs and small tables were hung from hooks arranged on the wall, and their locations could be modified by staff and visitors. According to the firm, their concept combined a blackboard wall and a “kit of parts” hanging in plain view: tables and chairs for the courtyard are stored on the wall, an idea inspired by houses in Shaker communities.8 Celebrating plurality and multivocality, the space was inspired by the idea that there is no single voice or “chair” who would direct the wall. The chairs – the audience – would be celebrated for its agency. At the time, the black wall behind the chairs was seen as a bonus – a chalkboard for use by the public to express themselves, and that could be used during talks and demonstrations.9 In the blank spaces where there were no chairs, visitors used white chalk to draw, write their names, leave messages, and engage others. When interviewed about Chairs of the Board for the museum member magazine Inside/Out, Jensen explained, “I see the Oak Street Plaza right now as a space that people just pass through, but the programming the Museum is working on for that space, combined with our project, will make it a place for things to actually happen.”10 Through what would eventually be an award winning design,11 Jensen sought to create a flexible structure on Oak Street Plaza to be used for one year as a multi-use, multi-purpose space. Museum leadership also saw it as a site that would allow the museum to accommodate forms of contemporary art practice that were poorly suited to the galleries, and to engage developing audiences. This cross-departmental ancillary space would allow the museum– a public institution founded as the “museum of the people” – to be more responsive, and better poised to take advantage of opportunities to collaborate with community groups.

The goal was to make Oak Street Plaza more than just a pass-through space. One of the core functions of the Plaza was to be a platform for programs of the museum’s contemporary art initiative, The Oakland Standard (2009-2012). The initiative coordinated activities ranging from experimental exhibitions to blogs, workshops and meals, workshops and lectures, and a residency. Chairs of the Board took an under-utilized museum space and activated it into a social place. Oak Street Plaza went from being the entrance way to the museum to being the front porch of the museum.”12

Years later, Chairs of the Board inspired the existing Chalkboard programming. In a city that by some estimates has over a thousand murals,13 this is one of the contexts that make the Chalkboard distinct: the museum’s conscious effort to activate both the wall and the space with cultural celebrations, hands-on activities, talks, and civic engagement projects like voter registration initiatives [Figure 8]. Today, engaging the museum collection and its exhibitions, and sharing space with contemporary voices of public who use the “chalkboard” as a site of personal expression or as inspiration as they participate in other museum activism, the Chalkboard offers local contemporary artists opportunities to connect past and present publics.

Murals on the Chalkboard took on a new meaning in 2020, when staff identified it as a site through which contemporary art could be used to promote the role of the artist as an agent of transformation and healing. In 2020, the Oakland Museum community took inspiration from its holdings like the All of Us Or None collection, and lesser known objects like monthly magazine Philopolis, or a “friend of the city,” which circulated from 1906 to 1916, and is in the museum collection. Founded by Arthur and Lucia Mathews following the 1906 earthquake that decimated large parts of the city, “it is the purpose of Philopolis,” the title page of the first issue announced, “to consider the ethical and artistic aspects of the rebuilding of San Francisco.” The staff continued to create prompts to engage the public: following the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision in 2022, which eliminated the federal constitutional right to abortion, museum staff used the Chalkboard to ask visitors for their thoughts and suggestions for action. Other recent artist mural commissions include a group mural made by the artist of Creativity Explored, a local art space for artists with developmental disabilities. Murals and public comment on the Chalkboard would function in cyclical dialogue, imagining and visualizing a new future together in a way that was especially meaningful as the country looked toward the end of the COVID 19 lockdown.

Cultural historian Robin Ballinger acknowledges the rich community mural tradition in California, but she raises important critiques how murals can be means by which government, business, and corporate sponsors to appropriate “community” and claim the appearance of collectivity, while allowing the ongoing policies, political economies, and practices of displacement of the very groups such murals claim to honor.14 Artists eventually become invisible. In this way, murals in cities like Oakland “paint over precarity. . .through particular renderings of ‘community;’” in the end ultimately serving “for the benefit of state and commercial interests.”15 The Chalkboard murals dynamically activate various institutional and artistic legacies and contexts, and exemplify how the Oakland Museum of California has engaged the meanings of public and public space.

1. “Monarchs, Marigolds, and a Mural,” OMCA press release, September 17, 2017

2. Ashvini Malshe and Ricky Rodas, “Oakland Museum and artists bring civic engagement to billboards,” Oakland North, September 24, 2018.

3. Michael J. Crosbie, “Kevin Roche on Architecture, Building Community, and Being of Service,” Common Edge, March 5, 2019 https://commonedge.org/kevin-roche-on-architecture-building-community-and-being-of-service/

4. Ibid.

5. Jeffrey Inscho, “How the Oakland Museum of California Blew My Mind (And Captured My Heart)”, Medium, March 16, 2017: https://medium.com/@jinscho/how-the-oakland-museum-of-california-blew-my-mind-and-captured-my-heart-d165ab54515b

6. “Public Sculpture/Urban Environment”, ART Newsletter, Oakland Museum Art Guild, September 1974.

7. Neibert, as in Sandra Caldwell, Public Sculpture/Urban Environment: An Analysis of the 1974 Exhibit at the Oakland Museum, unpublished (1975), p. 1. Oakland Museum exhibition archive files.

8. https://jensen-architects.com/work/omca-event-space/

9. Ibid.

10. Inside | Out, “A Conversation with Mark Jensen,” Summer/Fall 2011. Oakland Museum Archives.

11. The project was the 2012 winner of the American Institute of Architects, California Council (AIACC)’s Honor Award for Small Projects. The award is part of AIACC’s yearly Design Awards Program, which recognizes achievements in Architecture, Interior Architecture, Urban Design, and Small Projects, as well as the 25-Year Award and Maybeck Award. These awards are juried by a distinguished group of architects and members of the architectural profession.

12. Kelly A. Koski, Assistant Director, Communications & Audience Development, interview, 2012.

13. Casey O’Brien, “Mural, Mural, On the Wall: A Self-Guided Tour of Oakland’s Murals,” East Bay Magazine, February 5, 2021. https://www.eastbaymag.com/mural-mural-on-the-wall-a-self-guided-tour-of-oaklands-murals/

14. Robin Ballinger, “Painting over Precarity: Community Public Art and the Optics of Dispossession, Gentrification, and Governance in West Oakland, CA,” Journal of Urban Studies 8:1 (March, 2001), 83.

15. Ballinger, “Painting over Precarity,” 85.

Main image

Chelsea Ryoko Wong, Calling Home, 2025, Reproduction of digital artwork

Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco

Photo by Kamiko Fujii

Image description

A photo of a grey concrete wall in an outdoor plaza, featuring a brightly colored mural with a black background. The mural consists of five buildings in a range of colors and architectural styles, a bright yellow circle in the top left corner, two lamp posts near the left and right edges, and various people engaged in different activities. A string of red lanterns extends across the entirety of the composition. These red lanterns also appear on the two buildings closest to the right edge of the mural. The mural also features three white, gray, and black birds on the ground, four white birds flying, and three green and red birds flying. On the ground in front of the mural are three tables with chairs, a small sign on the wall immediately to the left of the mural, and a string of lights towards the top of the concrete wall.