“And there was violent relaxation”

Art’s Ambivalence Toward the Age of the Internet

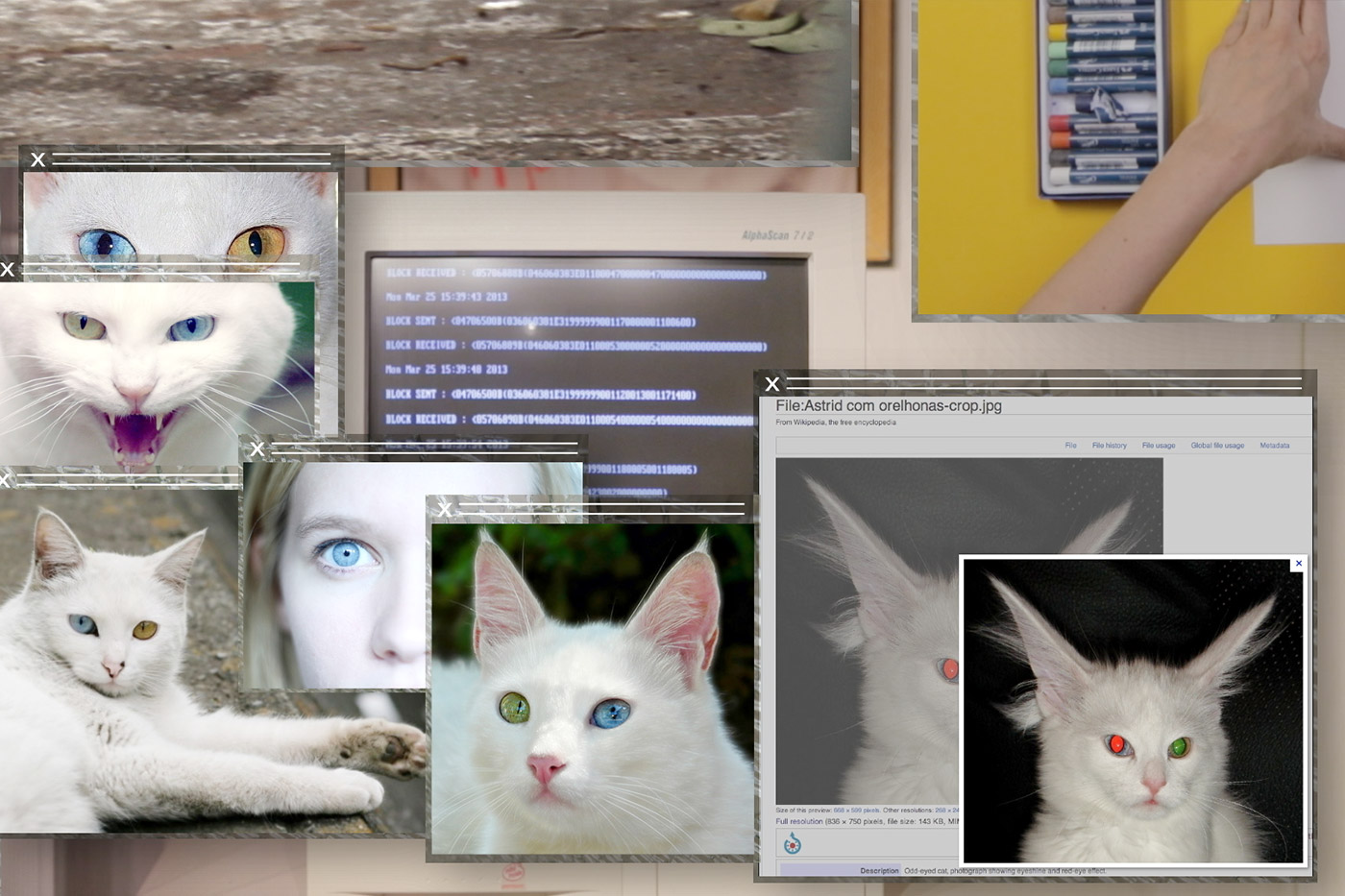

Is there any better way to describe those absorbing and disorienting hours spent clicking across the web, scrolling through social media, falling into never-ending YouTube holes than as “violent relaxation”?1 Camille Henrot invites us to sit back and let this experience take over with Grosse Fatigue (2013), a video featured in The Institute of Contemporary Art Boston’s exhibition Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today, which runs from February 7 to May 20, 2018.

We watch as the flotsam and jetsam of human knowledge floats by, from hypnotically rolling library shelves to cat photos and Wikipedia screen shots. Inspired by Henrot’s residency at the Smithsonian, the work historicizes the grosse fatigue of attempting to move through all of the ideas and images being constantly circulated online within the larger Enlightenment project of attempting to catalog, well, everything. Then by integrating the process of clicking between digital video files into the work’s visual stream, the video returns us to the specific context of what it means to know “in the age of the internet.” Henrot thus captures both the individual experience of being an internet browser and the larger sociocultural experience addressed by the exhibition: what can art tell us about how computer networking has rearranged the ways in which we see, understand, and organize the world?

Curators Eva Respini and Jeffrey De Blois start the clock on the internet age in 1989, the year that the Berlin Wall fell, protesters gathered in Tiananmen Square, GPS satellites were first launched, and Tim Berners-Lee proposed the protocols that would soon shape the World Wide Web. While computer networks had already existed for decades and internet use wouldn’t become popular for several more years, the curators argue that it was this confluence of social, political, and technological events that ushered in an era defined by the way information—and images—flow through computer networks.1 This view of humanity’s (and art’s) current condition assumes that the network is global and omnipresent, a belief that is probably shared by most of us reading this publication online. However, as the catalog reminds us, long standing digital divides persist: even today, less than half of the world’s population has access to the internet, and in many places that access is restricted by government filters and/or uneven distribution.2 So to talk about what it means to make art in the age of the internet we must also ask, who has access to the networked resources of the internet age? Who controls them? And who is in the majority of the population that disappears when we envision a global network?

Although this problem of access is prioritized in the scholarly work surrounding the show, it is surprisingly absent from the work itself. In one of the galleries we do find a pair of installations by Josh Kline that ask us to confront another group of people who are disappearing under the weight of the information resource economy: FedEx Delivery Worker Interview #1 (2014) and Saving Money with Subcontractors (FedEx Worker’s Head) (2015-17), which use video interviews and 3D-modeled head sculptures to quite literally put a face on internet business’ contingent labor class. Yet there is nothing in the show that asks us to think about the lacunae created by the selective reach of the network’s information flows, or what it means to make art in and around those spaces.3

Josh Kline, Saving Money with Subcontractors (Fedex Worker’s Head) (detail), 2015–17

Three 3D-printed sculptures in plaster with inkjet ink and cyanoacrylate, cast urethane foam packing peanuts, vinyl, cardboard, and MDF, 35 x 27 x 27 in.

Courtesy the artist and 47 Canal, New York, Photo by Caitlin Cunningham

© Josh Kline

Of course, Art in the Age of the Internet cannot be expected to fill every gap—contrary to much of the show’s early reception, it is not actually a comprehensive survey of all internet-based art produced since 1989. Instead, it is an inquiry into art’s often conflicted response to the effects of computer networks, traced through the broad categories that structure its galleries: Networks and Circulation, Hybrid Bodies, Virtual Worlds, States of Surveillance, and Performing the Self. The internet is thus positioned as a conceptual thread rather than a medium or even a common tool, although the exhibition is careful not to succumb to the temptation to dematerialize computer networks by including works like Trevor Paglen’s lush photographs of the undersea cables and orbiting satellites used by US intelligence agencies. These kinds of infrastructural objects are as necessary for our daily internet activities as they are for government surveillance, and the pair of images offer a stunning visualization of the depths and heights such infrastructure has reached. The show’s conceptual treatment of the internet also means that it is not focused primarily on net art (per se), although most of the works respond directly to computer networks as subject, source, and/or site of circulation. Instead, the show offers a series of cross-medium and intergenerational conversations that reveal how widespread the use of computer networks has become throughout contemporary art since the mid-2000s, while productively blurring the categorical boundaries that were drawn in the web’s early years between net art and the field of artistic practice that surrounded it.4

The most well-developed art historical link in Art in the Age of the Internet is between video and early internet art. Flying prominently on the wall of the Networks and Circulation gallery, Gretchen Bender’s American Flag (1989) is a frozen frame of a computer-generated image of a flag in the midst of a dissolve transition that Bender recorded from a televised sports broadcast and printed onto fabric. The description of the work emphasizes destabilization through digital manipulation, suggesting that the fragmentation of such imagery on television anticipated how images would be digitally broken up, decontextualized, and re-circulated on the web within the next few years. However, American Flag also explores broadcast television’s function as a communication platform that can inflect the meaning of nationalist symbols, an idea that was particularly fraught at the end of the Cold War, when television was popularly credited with accelerating demands for social change. American Flag thus takes its place in a history of video artists working with broadcast television that goes back to the 1970s, and that became a direct precedent for net art—these practices were interested in the same possibilities for visual experimentation and telecommunication offered by television that would later attract many artists to computer networks.5

Installation view with Judith Barry, Imagination, dead imagine (1991) in the foreground,

Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2018

Photo by Caitlin Cunningham

Another of internet art’s debts to video is made visible here by Judith Barry’s Imagination, dead imagine (1991), a monumental structure in the Hybrid Bodies gallery in which a large video cube sits atop a tall plinth. Each panel of the cube zooms in on a different piece of a human face as it is splashed with fluids, then digitally rendered clean, only for the process to be repeated over and over again. Barry’s work confronts the alienation of the body during the AIDS crisis, and how this state of alienation is exacerbated by the body’s fragmentation on the (photographic, video, digital) screen, but the artist also describes the cubic installation as a return of the body to minimalism. This emphasis on the work’s sculptural form connects it to the central theme of Before Projection, a concurrent exhibit at MIT’s List Center that looks at the long history of using monitors to build sculptural video installations in order to overcome the challenges of showing small-screen video in the gallery. (Before Projection is one of over a dozen related exhibitions and events being produced in the Boston area.)

Plagued by similar exhibition issues in its early years, net art eventually adopted both projection and monitor sculpture strategies from video, and these practices appear in later works throughout Art in the Age of the Internet. However, the curators also used this approach to show earlier, web-based projects by Olia Lialina and JODI.org, whose works My Boyfriend Came Back From the War (1996) and wwwwwwwww.jodi.org (1995) are loaded on classic computer towers for visitors to browse. Although these towers can be found sitting on desks in the galleries, the artists asked that they do not include chairs, resisting the “office aesthetic” by integrating the monitors into the installation, inseparable from the websites rather than simply a passive portal to them. This attentive approach to the specific needs of internet-based art extends into the Art in the Age of the Internet website, which functions as a core element of the show, with detailed information, rich design, contextual hyperlinking, and web-only exhibition components.6

Left: HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, thewayblackmachine (2014 – ongoing)

Right: Nam June Paik, Internet Dream (1994)

Center background: Gretchen Bender, American Flag (1989)

Installation view, Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2018

Photo by Caitlin Cunningham

Surrounding these historical conversations is a frame that, the exhibition argues, has shaped art’s investigations into computer networking since they began: the tension between celebratory and critical relationships to the internet. This is introduced by a pairing of works in the show’s entryway that also reinforces the link between video and net art: Nam June Paik’s Internet Dream (1994) and HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?’s thewayblackmachine.net (2014 – ongoing). Paik’s optimistic 1974 vision of an “electronic superhighway” that could video-link people around the world presaged how artists would later approach the telecommunicative possibilities of computer networks. With Internet Dream, a display of networked and digitally-processed images sprawling across fifty-two television monitors, Paik attempts to visualize how the electronic superhighway’s principles of mass participation and democratic image circulation are coming to fruition.

Installed on the wall across from it, thewayblackmachine.net complicates this vision. Constructed out of thirty monitors scrolling algorithmically-gathered social media content related to black activism and violence against African Americans, the work references both Ida B. Wells’s 1895 pamphlets documenting American lynchings and the selective web archive known as the Wayback Machine. With their own selective archive, HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN? argues forcefully against the de-racialization of computer networks that is endemic in digital utopianist models like Paik’s electronic superhighway, and foregrounds the significant role of racial discourses and histories in the formation of the internet’s social and communications infrastructure.

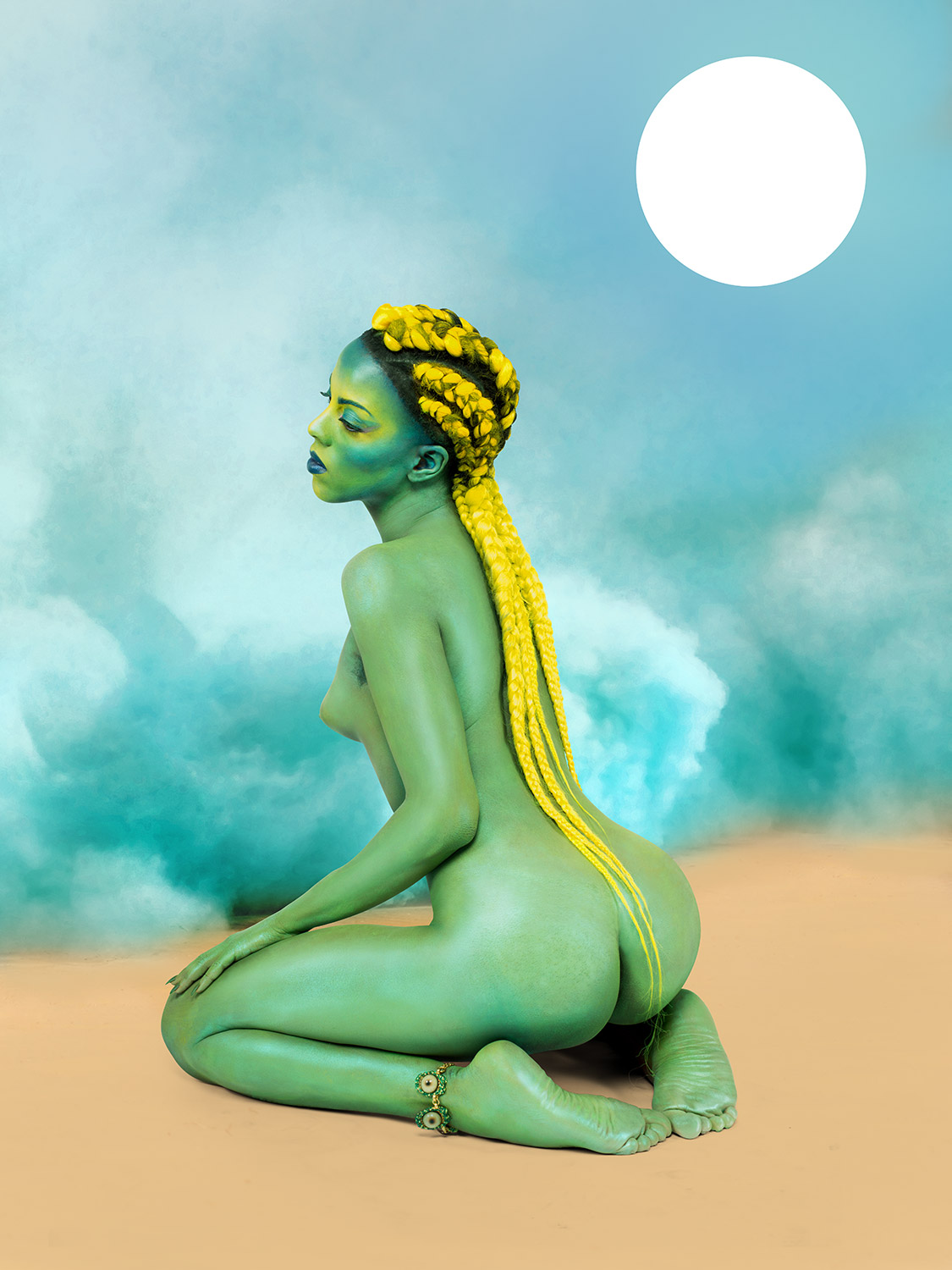

Art’s ambivalent relationship to the online environment is also subtly foregrounded in the work that the curators feature in the exhibition advertisements that are plastered all over Boston. Frank Benson’s Juliana (2014-15) is a life-sized bronze sculpture of artist Juliana Huxtable that Benson has covered with automotive paints to give it a greenish gleam, offset by her jeweled purple lips and the multicolored reflections that bounce off the sculpture’s surface. Juliana sits on a plinth in the middle of the Performing the Self gallery, which explores the effects of the internet on self-representation and identity formation, a major theme in Huxtable’s own practice. The sculpture specifically references the bright hues and otherworldly landscapes in which Huxtable depicts herself in self-portraits like Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm) (2015), also shown in Performing the Self, which imagines a world free from restrictive notions of gender and ethnicity and the violence that often accompanies them. At first encounter, the two portraits offer viewers a warm welcome, not just to the exhibition, but to the self-affirming virtual space that the artist has created by circulating images of her alternate world online. But next to Untitled in the Rage hangs Huxtable’s Untitled (Casual Power) (2015), a visual poem that reflects on experiences of blackness in the United States and the painful histories that motivate people to seek out “a mythical land,” histories that also shape and inform the world of computer networks that, the artist argues, cannot be isolated from their offline contexts. Thus like the pairing of Paik’s and HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?’s installations in the entryway, situating Huxtable’s self-empowering portraits in the fuller context of her practice suggests that we cannot disentangle art’s aspirational and critical visions of computer networks.

This structural tension can be found throughout Art in the Age of the Internet. Moving backwards through the exhibition, we come next to the States of Surveillance gallery, which thematizes that unavoidable feeling of being exposed when we go online with works like Lynn Hershman Leeson’s CybeRoberta (1995 – 1996) and Tillie (1995 – 1998), a pair of dolls that look back at the viewer with tiny cameras that can be remotely controlled on the artist’s website. But hanging on the wall behind the dolls is Rabih Mroué’s The Fall of a Hair: Blow Ups (2012), a reminder that computer networks have also offered individuals the unprecedented ability to look back. The Blow Ups are a series of prints that Mroué made from cell phone photos found online that show gunmen pointing directly at the camera. Circulated by Syrian protestors, the images reference the practice of citizen journalism, which proposes that we can use digital imaging and the distribution platforms of the internet to gaze back at actors as powerful as national governments. Mroué’s prints, however, are blurry, an acceptance of technical artifacts in the printing process that simultaneously resists the aestheticization of violence and highlights the complexity of the networked gaze, which is as much a tool for control as it is a tool for resistance.

The Virtual Worlds gallery features works like Cory Arcangel’s Super Landscape #1 (2005) and Cao Fei’s RMB City: A Second Life City Planning (2007), which revel in the playfulness of gaming and the experimental environment of virtual reality platforms. These sit in stark contrast to Harun Farocki’s Serious Games IV: A Sun with No Shadow (2010), which highlights the violence that has seeped into our virtual worlds by documenting the military’s dual use of VR gaming: to prepare soldiers to fight, and to attempt to heal their resulting psychological wounds. Many of the other Virtual Worlds projects examine the combination of seduction and fear that shapes our relationships to alternate realities, from the haunting animated landscapes through which the Annlee character wanders in Pierre Huyghe’s One Million Kingdoms (2001) to the ominous thrill of View of Harbor (2018), a site-specific VR installation that Jon Rafman has produced for the ICA’s famous harbor view.7

The Hybrid Bodies gallery is structured around the many promises, and perhaps even more failures, of the fantasy that we can blend the biological and the mechanical to live in a better world, or at least a better skin.8 This is exemplified by Sondra Perry’s Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016), which sits in the far corner of the gallery from Barry’s monumental video sculpture, forming a multi-decade arc of attempts to reconcile the estrangement produced by the body’s representation on screen. Perry’s installation features an exercise bike on which viewers are invited to sit. Settle in, and you’ll find yourself gazing up at a 3D avatar of Perry looming over you from the three video panels at the top of the bike. The avatar narrates the exhaustions of being a black woman in the United States while soothing music plays in the background and fleshy textures, a digital rendering of the artist’s skin, move across the blue screen behind her. Graft and Ash examines the desire to escape into virtual representation, while confronting the inaccessibility of this escape for so many bodies—Perry finds her avatar limited by the idealization of thin, light-skinned bodies as the software fails to accurately render her full shape and she is forced to appear in front of a chroma-key blue screen in order to correctly process her dark skin.

Returning, finally, to the beginning of the show, the Networks and Circulation gallery, we find a range of works that capitalize on the freedom with which images move across the network. Thomas Ruff’s nudes series (1999 – ongoing) and Penelope Umbrico’s Suns from Sunsets from Flickr series (2006 – ongoing) recontextualize the web’s seemingly endless troves of vernacular imagery, ranging from tourist photography to pornography, while Laura Owens plays with the internet’s famously democratic tendency to level the low- and highbrow as downloaded images of Garfield comics and Juan Gris paintings jumble together on her screen-printed canvas.9 But we also see works that challenge the apparent neutrality of the paths along which these images travel. Taryn Simon and Aaron Swartz’s Image Atlas (2012), a website that is projected here onto the wall, allows users to simultaneously enter keywords into several different search engines from around the world with very diverse results, thereby exposing the fiction of the objective algorithm. And Hito Steyerl’s Liquidity Inc. (2014), which the ICA recently acquired and has installed in an adjacent room in conjunction with Art in the Age of the Internet, uses the principle of liquidity to explore how labors of work and labors of the body become distorted by the network’s intersecting flows of information, culture, and capital.

The exhibition includes far more work than can be covered here—a visit to the website will help close the inevitable gaps. Taken as a whole, Art in the Age of the Internet suggests that art has never fully lost its optimism for the equalizing potential of communication networks, its fascination with the creation of new representational worlds, and its desire to exploit the internet’s ability to simultaneously expand and collapse distance, sending information and images flying around (part of) the globe. At the same time, it highlights art’s essential role in maintaining a critical relationship to these possibilities, grounding our understanding of the age of the internet not through an embrace of its technologies, but through a careful excavation of the realities it has shaped and the realities out of which it has emerged.

1 Eva Respini, “No Ghost Just a Shell,” in Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, ed. Eva Respini (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 13–14. Computer networking began in the 1950s and 1960s with the invention of the modem and the development of the Defense Department’s ARPANET, but internet use didn’t begin its rapid rise in popularity until after 1994, when the first commercial web browsers made the internet relatively affordable and intuitive to use for the first time.

2 The World Bank estimates that about 45% of the world’s population was able to use the internet in 2016. International Telecommunication Union, “Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population),” World Bank World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report and database, accessed February 19, 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS.

3 Although the issue of internet access is absent from the exhibition, there are artists addressing it in their work. For example, in 2015 Cuban artists Julia Weist and Nestor Siré launched !!!Sección A R T E, a compilation of artworks they contribute to El Paquete Semanal, which is a weekly media collection distributed in Cuba on physical media via “in-person file sharing” that offers an alternative network in a place where internet access is scarce. Rhizome recently collaborated with Weist and Siré to produce a bilingual version of !!!Sección A R T E.

4 The integration of net art with other practices from the 1990s in Art in the Age of the Internet follows the example of recent exhibitions like the Montclair Art Museum’s 2015 Come As You Are: Art of the 1990s.

5 Many artists who were using broadcast and satellite television in the 1970s and 1980s also turned to computer networks in the 1990s. See, for example, Van Gogh TV’s Piazza Virtuale (1992) at documenta, or Douglas Davis’s use of the web to finally break through to “the viewer on the other side of the then-imperial TV screen” in The World’s First Collaborative Sentence (1994).

6 In addition to goodies like a live video feed of the States of Surveillance gallery, the Art in the Age of the Internet website featured web-only commissions by Olia Lialina (An Infinite Séance 3, 2018) and HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?.

7 Pierre Huyghe’s One Million Kingdoms is part of the No Ghost Just a Shell (1999–2002) project, in which Huyghe and Philippe Parreno purchased the Japanese manga character Annlee and distributed it to fellow artists, including design firm M/M Paris, whose Annlee wallpaper hangs behind the video in Art in the Age of the Internet. In 2002, Huyge and Parreno started a corporation in Annlee’s name and sold the character’s representation back to itself, thereby opening the project onto the questions of copyright, image circulation, and control of representation that are central to the internet.

8 The Hybrid Bodies gallery is infused with Donna Haraway’s cyberfeminist vision of the cyborg as a refusal of artificially-imposed dichotomies like nature/culture, female/male, biology/machine, a model of hybridity explored most directly in Anicka Yi’s Fever and Spear (2014).

9 Painting is not dead in the age of the internet. In addition to Laura Owens’s untitled (2016), other works in the exhibition that combine digital and hand techniques to introduce network themes onto the canvas include a pair of untitled paintings by Albert Oehlen (2008) and Avery Singer (2015), and a series of Chat Paintings produced in oil by Celia Hempton in 2015 and 2016.

Further Reading

Christopher McGahan, Racing Cyberculture: Minoritarian Art and Cultural Politics on the Internet, Routledge Studies in New Media and Cyberculture (New York: Routledge, 2008).

David Joselit, “Tale of the Tape,” Artforum International 40, no. 9 (May 2002): 152–55, 196.

Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), 149–81.

Janet Abbate. Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1999.

Jonathan Crary, “Critical Reflections,” Artforum International 32, no. 6 (February 1994): 58–59, 103.

Jorge Luis Borges, “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins,” in Borges: Selected Non-Fictions, ed. Eliot Weinberger, trans. Esther Allen, Suzanne Jill Levine, and Eliot Weinberger (New York: Penguin, 2000), 231.

Megan Driscoll, “Color Coded: Mendi + Keith Obadike’s Black.Net.Art Actions and the Language of Computer Networks,” The Black Scholar 47, no. 3 (July 3, 2017): 56–67, https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2017.1330110.

Omar Kholeif, Emily Butler, and Seamus McCormack, eds., Electronic Superhighway: From Experiments in Art and Technology to Art after the Internet (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2016).

Nam June Paik, “Media Planning for the Postindustrial Society: The 21st Century Is Now Only 26 Years Away,” Media Art Net, 1974, http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/source-text/33/.

Peter Weibel and Timothy Druckrey, eds. Net_condition: Art and Global Media. Graz, Austria : Karlsruhe, Germany : Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2001.

Tim Berners-Lee and Mark Fischetti, Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web by Its Inventor (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1999).

Main image

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue, 2013

Video, color, sound, 13:00 minutes

Courtesy the artist, Silex Films, and kamel mennour, Paris/London

© 2016 ADAGP Camille Henrot