ALL THAT GLITTERS

I first encountered the art and alchemy of Nancy Lorenz in the fall of 2014, when a catalogue from the McNay Art Museum, Beauty Reigns: A Baroque Sensibility in Recent Painting, crossed my desk. Though I had missed the exhibition (curated by René Paul Barilleaux) in San Antonio, I arranged a visit to the artist’s studio in New York.

The work that had so caught my eye in the catalogue was a group of what Lorenz calls Pours, abstract compositions involving gestural applications of water-gilded gesso. Surprisingly modest in scale, these paintings turn on the tension between arid fields of pigment and sumptuous cascades of gold, silver, and platinum. The artist’s colors, dryly brushed on unprimed burlap, recall the pre-industrial or commonplace materials of Arte Povera minimalism. No less nuanced are the tones of the gilding: lemon gold, for instance, over green earth.

Leaning against one wall of the studio were painted panels, some destined for monumental murals. Like Whistler’s fireworks, these were objects of incandescent beauty. Alongside the mineral pigments and noble metals that I recognized from the Pours, were pools of lacquer and fields of inlay. In contrast to these traditional techniques (water gilding, mother of pearl inlay) were other, less familiar materials. Beneath the layers of metal leaf and gesso was a water-based molding material. Aqua-Resin, I learned, had made the Pours permanent.

Nancy Lorenz, Blackened Silver Pour Box, 2016

Blackened silver leaf, gesso, clay and lacquer on paulownia box

13.5 x 15.5 x 7 in.

Photo: Adam Reich

After numerous experiments, the same two-part composite had been used to transform corrugated cardboard into a ground for gilding. In a painting like Moon Gold Cardboard I (2013), the abstract scratches and striations coalesce into a landscape composition, an evocation of sea, sky, and slanting rain. This motif, studied from nature in the artist’s sketchbooks, is a recurring theme in paintings large and small, and in the panels that together form folding screens.

Large-scale commissions occupy not just Lorenz but numerous studio assistants. Each has been trained in the traditional techniques that Lorenz acquired as a restorer of antique lacquer. I asked Lorenz about the tension in her work between time-tested methods and more experimental techniques. A traditional Japanese box (of the wooden sort used to keep tea ceremony vessels) is adorned, for instance, not only with lacquer and inlaid agate, but with charcoal and broken mirror, first used to depict Carbon in the periodic table series. This takes us back to the beginning.

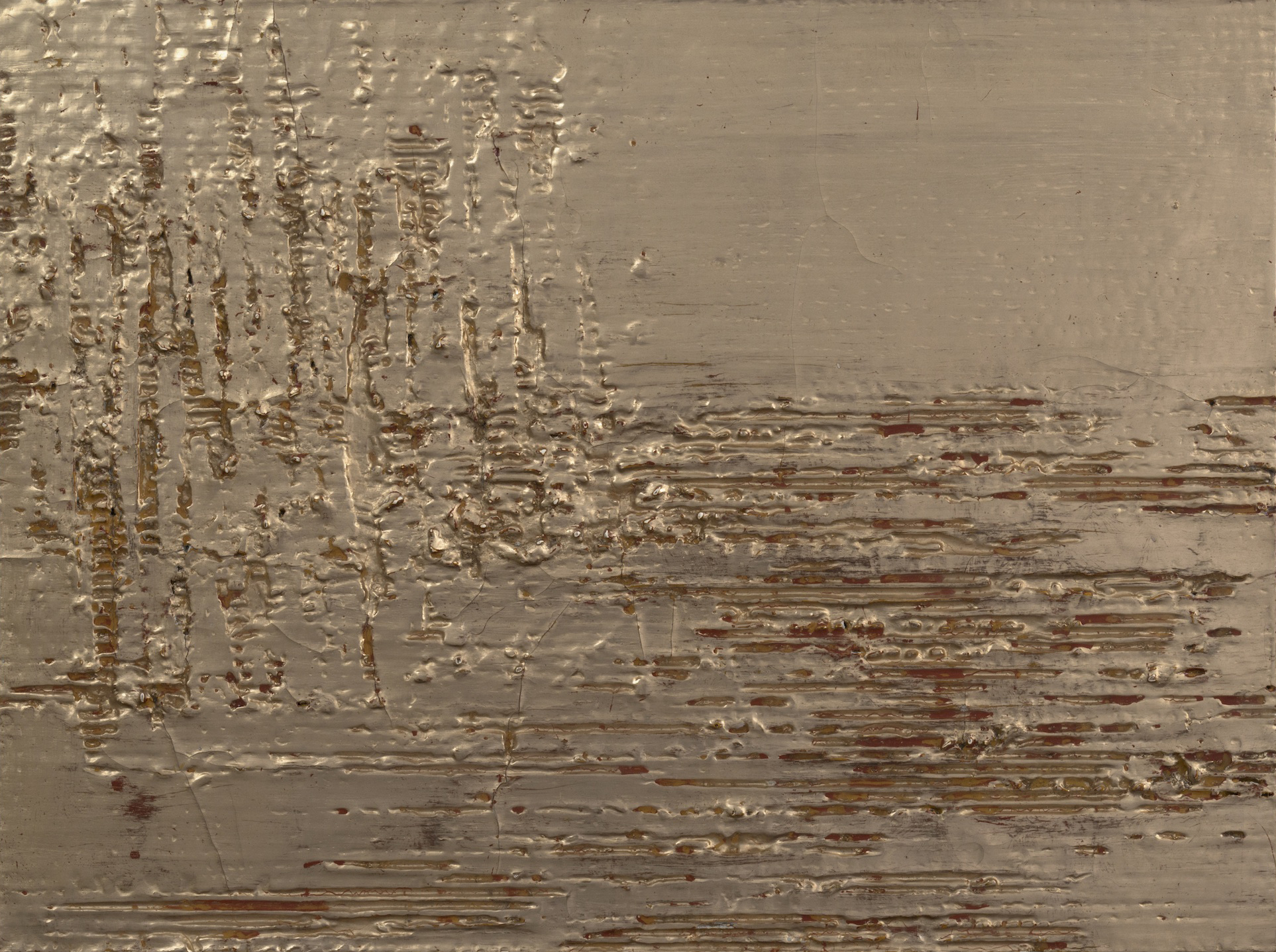

Nancy Lorenz, Moon Gold Cardboard (I), 2013

Moon gold leaf, cardboard, clay and resin on panel

18 x 24 in.

Nancy Lorenz: I moved from Texas to Tokyo when I was teenager, and lived there for five years. They were my high school years, and it was there that I really learned to look at lacquer and appreciate fine craft.

I went from that to the University of Michigan, where big abstract painting was the thing, and so I had yet another, very different, way of looking at art. Eventually, my ideas about materials and modernism came together, and it happened in Rome where I spent my last year of graduate school. There I discovered gold-ground Renaissance panel painting, and had the idea of incorporating gilding into my work. At the same time—and on the completely opposite end of the spectrum—I was very influenced by Arte Povera. I was attracted to the visceral, irreverent use of the material in these paintings. Then I came to New York, and Julian Schnabel was throwing plates and resin onto canvas, and I thought that was so big and bold and fabulous. So in my own studio, I had two things going on at once. I needed to support myself, and had my own business restoring mostly 18th century lacquer—Coromandel screens and English adaptations of lacquer. I lived where I worked so I had other people’s museum-quality antiques, alongside my own experiments. In my own work, I was mixing these traditional techniques with more contemporary materials, and getting mixed results. Some of them didn’t last. I didn’t want a collector coming back because the silver leaf in one of my pieces had tarnished, or the cardboard was falling apart. Sometimes I want the tarnish, and when I allow it to happen by allowing it to oxidize, it’s clearly intentional.

Ariel Plotek: This idea of control, of arresting the aging process, makes me think of the Ise Shrine, which is rebuilt every twenty years—a ritual of rebirth and renewal.

Lorenz: Right. Destroying in order to rebuild. I got involved—albeit very late—with the campaign led by the designer Tomas Maier to save the lobby of the Okura Hotel. It’s a monument of Japanese modernism, built in the early 60s, and was my family’s first address when we moved to Tokyo. It’s no overstatement to say that that place—in particular the lobby—significantly shaped my aesthetic. The pared-down minimal décor and angular flower arrangements seemed so harsh and cold to me at first. When the time came, though, to leave and we lived in the hotel again five years later, I realized how familiar and comforting that aesthetic had become. So, like many people, I was very saddened to hear that the hotel lobby was going to be torn down to make way for something new. I suppose they think they can build something better? I’m remembering another side to that coin, which Junichiro Tanizaki talks about in his essay, In Praise of Shadows, when he celebrates the crack in the teacup and the patina of age. If there’s a crack, you paint it gold, rather than fill it in and make it look like it never happened; you preserve the patina of age, celebrate that imperfection.

This interests me also as an artist. Anyone who’s worked for me knows how to do things the old-fashioned, painstaking way: how to make rabbit skin glue, how to make gesso, how to make things more permanent. But I also use iron filings, and they rust—which is fine, as long as that’s something I’m looking for.

Plotek: And it might well have been, for instance, when you were drawing inspiration from the periodic table of elements.

Lorenz: The table of elements was the perfect metaphor to allow me to explore and organize my interest in materials. It allowed me to experiment. I went through the elements and interpreted them in sometimes poetic ways. It was important that the paintings work on an abstract level, incorporating the wide array of art historical references which I had picked up along the way, and yet I still had a concrete physical reference. In the case of Gold and Silver, the metals are used more literally. But Palladium, for instance, includes flocking on velvet.

Plotek: You also trained as printmaker. Are you ever tempted, now, to experiment with multiples?

Lorenz: This brings us back to the corrugated cardboard, which I first began using to make prints. I realized I could splice and reveal different surfaces of the cardboard and its ridges and valleys created this irregular stripe. But when I made these impressions—and this would happen whenever I made prints—I would always become more interested in the process than the result. I had these remainders of reworked cardboard sitting around, and I tried gessoing and gilding directly on them, which didn’t hold up very well. Corrugated cardboard isn’t exactly an archival material. It’s far too acidic. But then I figured out a way to seal the cardboard, and you’ve seen the result. I love the combination of everyday material and refined craftsmanship.

So, to answer your question, I have thought about making multiples. I’ve been able to experiment a little with porcelain, which could be beautiful as an edition. If the right opportunity were to come along I would love to try casting the cardboard pieces in bronze or iron. But then again, do we really need ten of them?