ABLEIST SPACE // [DISABLED BODY]

On any trip to the museum, or excursion to a new gallery, a knot twists in my stomach, signaling my subconscious anticipation of the difficulties I regularly encounter when I try to make my way through an exhibition. As I stand at the threshold of a contemporary art space, I know that what lies beyond is not accustomed or prepared to accommodate my body, sick and disabled.

Ableism, like most systems of prejudice, is woven deeply into our language, and greatly concentrated within the institution of the museum. It is the vast array of beliefs and systems that have constructed the idealized body, regarded as the perfect norm of the species. This ideal is considered the essential corporeal form, and thus fully, truly human. A stark and direct parallel has been created, which entraps the disabled body into being defined and imaged as a lesser, imperfect, and sub-human state of existence.

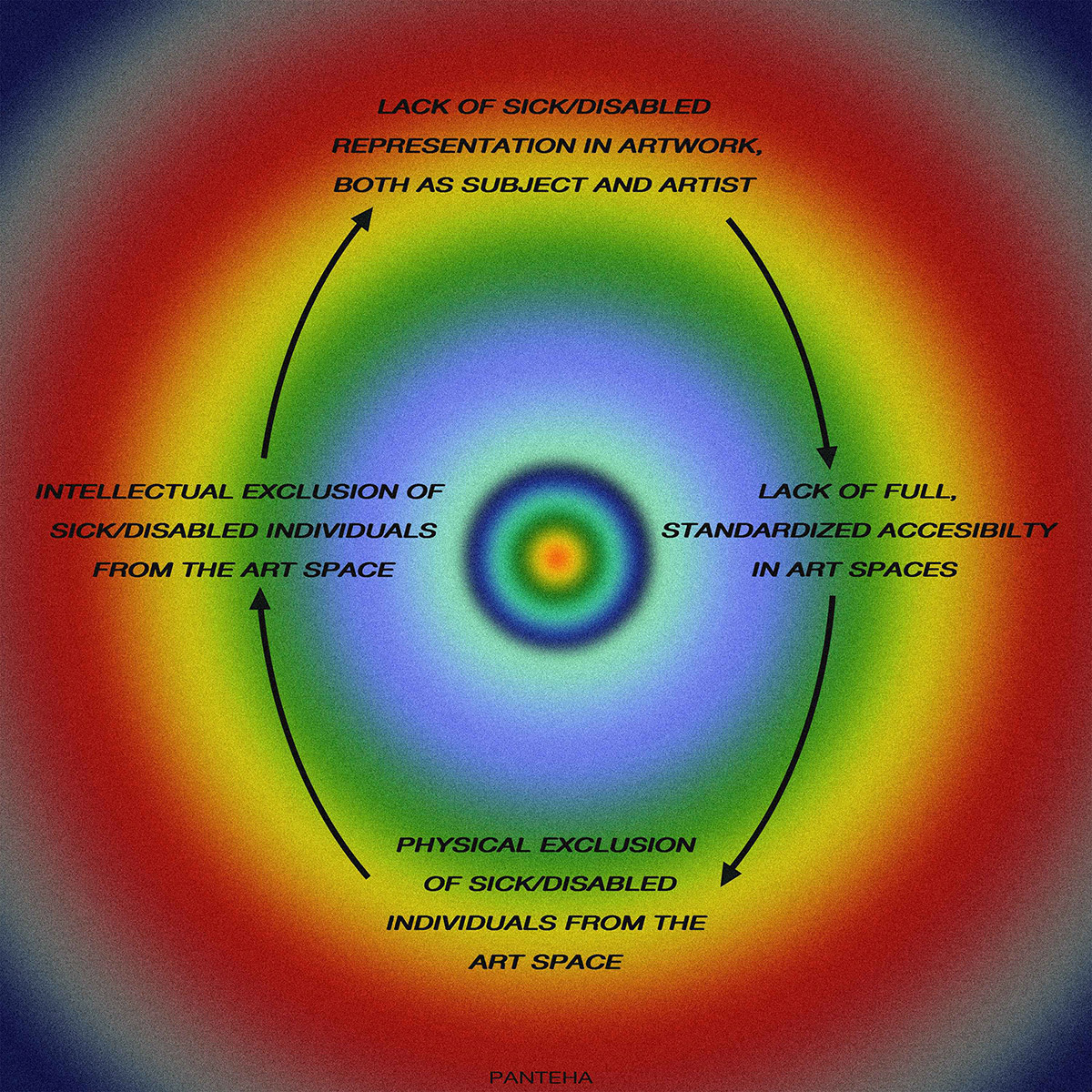

Ableism is a term that has risen significantly in its usage in the past decade, though its definition is still not common knowledge, nor is its role in the cultural spaces we rely on. The able-bodied individual moves through the art space with very little consideration as to how it is constructed to cater to their comfort, causing distinct discomfort and challenge for all those who are not able-bodied like them. Navigating the art space as an ill/ disabled individual, one becomes hyperaware of the stark lack of accessibility. It is vitally important to understand that the othering of the disabled body in the physical space of the museum correlates directly to the stark lack of representation of sick/ disabled bodies in the artwork exhibited, and in the artists represented. The lack of accessibility within the art space creates a closed feedback-loop, where the sick/ disabled are unrepresented, and treated as anomalous visitors. The hostility of the space discourages or altogether prevents disabled individuals from fully entering the space, cementing a vicious cycle of exclusion. These systems of (mis)representation are built to keep the sick and disabled hidden away, taboo bodies treated as anomalies.

There are currently no enforced standards for audio transcription, assistive listening devices, sign language interpretation, or closed captioning in museums. There is also no standard to follow when considering access in the curation of an exhibition. I have personally experienced great difficulty navigating exhibitions due to my mobility aids, whether I am using my cane, forearm crutches, or a wheelchair. On many occasions, I have encountered spaces that I cannot access at all. It’s not just that many spaces don’t have elevators or ramps, but also that many works are installed according to an ableist ideal: the only body envisioned navigating them is fully able-bodied.

One poignant example of simultaneous inaccessible architecture and curation can be found in the lobby of the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where they curate a rotating mural on the landing of a staircase. These works are stunning, intricate uses of the space, and often bleed down from the walls onto the floors and steps. The Hammer has an elevator available, but taking it means completely bypassing the mural, and makes any interaction with the work virtually impossible for those who are unable to climb the stairs. While this is a crystalline illustration of an art space which only able-bodied people can move through unimpeded, this same principle of innate inaccessibility is nearly impossible to avoid in all aspects of the art space. Fundamental inaccessibility bleeds seamlessly from the architecture into the art works, and then into the stratosphere of criticality suspended above the pieces.

We need a critical examination of artwork and disability aesthetics, too. Take for example the 2019 “Foundation of the Museum: MOCA’s Collection” show, held at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. In a piece by Chris Burden titled Exposing the Foundation of the Museum (1986), the ground of the museum was torn up, the building’s foundation literally exposed. This poetic and interactive piece invited the viewer down a flight of steps into the excavation tunnel, inviting them to closely examine the building’s concrete footing, but I wasn’t able to descend. I had a similar experience when attending the 2019 “Dirty Protests” exhibition at the Hammer Museum, where I encountered Mike Kelley’s City 000 (2010): a visually striking piece hailing from Kelley’s sculptural series centered on the fictional city of Kandor. The piece invites the viewer to climb a set of wooden steps (after donning protective booties) to peer over the top of a stony monolith, where a colorfully lit city composed of delicate glass structures fountains upwards. These pieces were undoubtedly exciting for the able-bodied viewer: a chance to physically engage with an artwork is never passed up. But for those who cannot easily descend and ascend even the shortest flights of steps, the meaning shifts. What was intended to be an intimate experience for the viewer instead became passive witnessing of experiences I could not engage in. The sparkling glass city became sequestered, and impenetrable. The museum’s foundation, exposed as it was, essentially remained as inaccessible to me as it had been when buried tidily beneath layers of concrete. A deep irony is situated here in the examining MOCA’s inaccessible foundation. It calls in to question just how rooted ableism is within everyday cultural spaces. Pillars of ableism often do not simply exist beneath the surface, but are in fact propping up entire structures, unbeknownst to those passing above.

Let’s return to my definition of “ableism”: it is a system which relies on an impossible bodily standard to ostracize, invalidate, and dehumanize those who cannot adhere to it. This conflation of ill or disabled with “lesser” is reflected in the ableist standard of our language, behavior, and the social cues we operate upon: they rely on imagining the ill/ disabled body as not only sub-human, but something that is to be hidden. Take for example the notion of “standing up” for oneself, or the negative connotations of something “falling on deaf ears,” or even the extremely casual and colloquial usage of the word “lame.” The language we are taught makes it harrowingly easy to build a subconsciously degrading imaging of the sick/disabled body. This everyday ableism contributes to why there is such a gaping void in the representation of the sick/ disabled in the artwork we see.

I am by no means criticizing artists like Burden or Kelley for using inaccessible, interactive features in their installations, nor am I criticizing the institution for including these pieces in their shows. Rather, I am criticizing the complete lack of consideration of the disabled experience in the contextualization of these works. It is clear the curators took no consideration to accommodate the experience of an individual who will not be able to engage with the artwork as intended by the artist. Instead, the art space operates with the erasive assumption that all individuals who enter the space will have the same access and physical experience of the work. In these two instances, no validity is being given to the perspective of those who must watch from a distance as others engage with pieces, and whose experience of the space is refracted through secondhand interactions. The meaning of the art space often shifts dramatically when viewed through a sick/ disabled lens, and this large disparity between the able-bodied and disabled experience within the same space speaks to how fundamentally entrenched ableism is in every aspect of the construction, curation, and navigation of the art space.

In my own practice, I employ accessibility as a tool, both withholding and over-extending it as a means of casting light onto the ill/ disabled experience while actively combatting our erasure. Last year, I created a performance piece titled And I Gaze, which invites the viewer to climb up a flight of metal steps to peer through binoculars across the room, pointed at a small video projection on the opposite wall. And I Gaze harkens back to my experience with the Chris Burden work, Exposing the Foundation of the Museum. I created a piece that, even as the artist, I would not be able to engage with as I had intended for it to be experienced. Instead, I am limited to watching my able-bodied audience members interact with it as I had hoped.

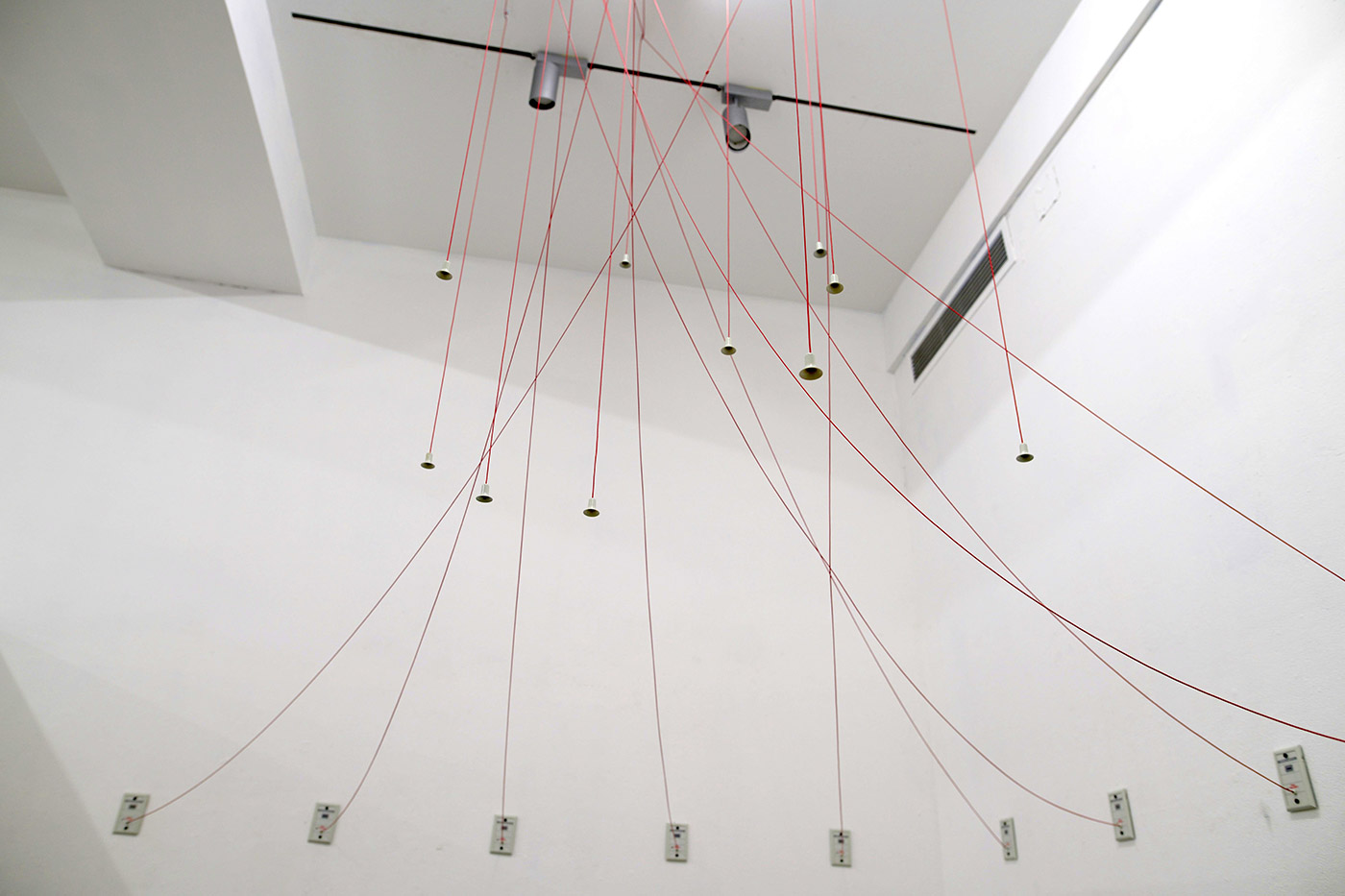

Another piece, entitled 5 Alarm (Pull For Help) (2019), uses assistance panels, which are found in hospitals, both in bathrooms and beside beds. Patients pull them when they need immediate and emergent assistance. In this work, the cords dangle ever so slightly out of reach, speaking to the often fundamentally inaccessible nature of “help.” The body feels so highly alienated in the medical space, where it is treated as a specimen and subjected to nuanced violence that is normalized in the Western medical complex. Not only is the world around the ill/ disabled built to be inaccessible to the sick, the emotional languages we are taught to speak—specifically the harmful conflations of empathy, shame and pity—further alienate the ill/ disabled bodies. In this installation, the viewer was put into a position in which all calls for help were dangled teasingly above them: out of reach, and forbidden.

In performance-based video-installation works that I have created, documenting my own body in discomfort, pain, and states of vulnerability, I image the sick/ disabled body that is often difficult to witness. We must constantly question what is making us uncomfortable, and among the most difficult things to face is the disabled, uncensored body. My piece NATURAL DISASTER features footage of a performance I did with my wheelchair when it was first delivered to my apartment. I documented the painstaking cycle of confronting my own degeneration, gesturing toward a universal fear of vulnerability. The video itself is installed on an analog CRT monitor that rests upon a wheelchair, evoking the body as well as the “defunct.”

Panteha Abareshi, NATURAL DISASTER (video still), 2019, 8mm color negative, performance for video, sound composition

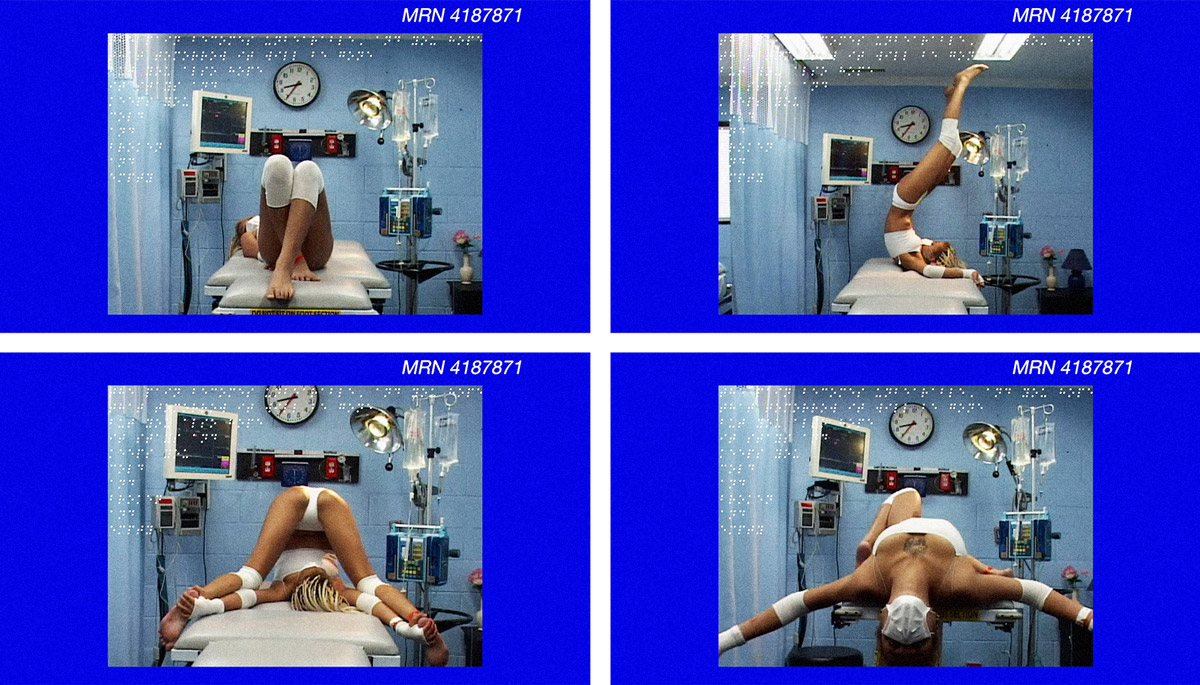

In work such as my piece NOT BETTER YET (2019), I document one of many, iterating confrontations with the reality that there is no “better” for my body, my illness. The language we have around illness creates a linear plane of existence, where the sick/ disabled individual is forced to reduce their experience to the binary of being/ feeling “better” or “worse”—words which are also connected to ultimately moralistic connotations of “good” and “bad.” NOT BETTER YET fervently captures one small moment in the endlessly harrowing cycle of accepting that I will be sick for the rest of my life—an endless process which seemingly starts anew with every worsening of my condition. The piece captures a contortive bodily performance done on a hospital bed, while a sound composition using recordings of my doctors and nurses that I captured in the hospital play over the super 8mm footage. I made this piece after a particularly intense hospitalization, conceptually driven by a conversation I had with my father. He had come up to LA to help me transition from the hospital back to my apartment, intending to only stay a few days. He postponed his flight back three times, and soon asked if he should postpone his departure a fourth time, saying just wanted to stay until I was “better.” This brought me to trembling tears, as I stumbled over my words to explain to him that if he stayed until I was “better,” then he would never leave. NOT BETTER YET marks the beginning of my own harrowing and endless reconciliation with getting “worse” for the rest of my life, and fighting to break from the ableist linear narrative of illness that negatively connotes degeneration.

There are, of course, examples of works that represent the ill/ disabled body, though few of them are well-known. Jesse Darling creates sculptural works, bending and warping the body of household items into wounded forms, and elegantly articulating the frustrations of inability and inaccessibility through their installations. Sue Austin’s groundbreaking performance diving in the ocean in a specially made wheelchair subverts all norms around the artistic subjects we are comfortable with. The work beautifully images the disabled body while simultaneously questioning its exclusion and isolation, and the othering of such a large subset of the global population. A piece that is of great personal importance to me is Frank Moore’s erotic performance Out of Isolation (1989), a humorously topical title. The video consists of two separate scenes, mostly seen in long, uninterrupted shots. Moore lays naked on a mattress, while a woman first cares for him, then begins teasing him sensually and sexually. This video broaches a taboo in vital need of destigmatization: the sexual imaging, representation and empowerment of the disabled individual. These artworks chafe at the discomfort felt by able-bodied viewers when witnessing a disabled body, in artwork parallel with the physical discomfort the disabled body experiences when navigating the art space itself. The lack of representation of disabled bodies in artwork signals to the able-bodied viewer that the museum is not a space where the disabled existence is normalized, or welcome.

Sue Austin, Creating the Spectacle! (film still), 2012. The full film can be viewed here.

The solution to the complex, deeply-rooted and normalized issue of ableism is a concerted effort to amplify and normalize the sick/ disabled perspective and create space for its presence. Pointing out ableism and inaccessibility should not be a means of shaming, but rather an acknowledgement that we are living in a world built for the able-bodied. Ableism is a decaying tooth in the cavernous mouth of our society, and we are fundamentally unequipped to cope with the pain it causes, or to safely approach its extraction. The language we are comfortable with when critically discussing the art space has not yet extended fully into the consideration of disability perspectives and aesthetics, both out of a lack of standardized, disability-conscious language, but also because the ableist lens which criticality is refracted through makes it seem that there is no pressing need for such perspectives.

Making change within the art space shouldn’t involve excluding works that have physical access barriers. Instead, we must begin acknowledging and critically examining the intentions behind these barriers. If a video piece is not captioned, there is a vital need for a discussion around the artist’s intentional decision to not accommodate d/Deaf individuals. There is a distinct hierarchy put into place when artists don’t include sensory transcription—a term I use when discussing the translation of a work across modes of experience, such as from sound to caption or image to description. Sensory transcription is a widely under-valued, unexplored, and undiscussed practice, and yet it crucial for the creation of radically accessible spaces. While audio captioning is an example most are familiar with, it becomes so suddenly taboo when discussing visual or tactile representations of sound, not only because artists privilege medium specificity, but also because we as an audience have never been told to be critical of our sensory experiences, and how they might be radically different for those who are differently-abled. It is crucial that any individual artist thinks beyond the confines of their own physical body, but it is not a simple task by any means. I am begging for new, radical forms of empathy that abandon the paradigm of the self. Equipping the societal collective with the language and context to frame the experience of the disabled body is a massively and overwhelmingly large undertaking. But I do believe, with some acknowledged bias, that the art space is a powerful cultural space, capable of fostering change from within.

The most significant step towards accessibility in the art space has perhaps been completely involuntary. The emergent need to establish, validate and maintain the art space digitally in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has made the art space more universal than it could ever possibly be when bound to the physical realm. It is a difficult thing to concede, but there are institutions that cannot be repaired without immense foundational upheaval, and the opportunity has presented itself with the unavoidable need to bring the museum and gallery experience into the fully digital space. This is a critical moment, in which the art space is being collectively redefined while suspended in a highly accessible space. Decisions made when implementing accessibility in the digital art space are laying the groundwork for actions that will be taken in the physical art space. It is a unique opportunity to set a new precedent of radical inclusivity that must not be ignored.

Main image

Panteha Abareshi, 5 Alarm (Pull For Help), 2019

Image description: A photograph of an artwork entitled “5 Alarm (Pull For Help)” by Panteha Abareshi. The photo shows a series of 8 assistance panels, like those found in hospitals for patients to pull when they need immediate and emergent assistance. The panels are rectangular and grey, each mounted on a white wall and attached to a red cord that runs up to the ceiling. In this work, the cords dangle ever so slightly out of reach, speaking to the often fundamentally inaccessible nature of “help.”