A Silent Roundtable Discussion

on Disability and Inclusion in Art Conservation

Art conservation is a field dedicated to preserving art and historic artifacts for current and future generations. It is currently practiced by professionals with knowledge and skills in artistic practice, science, and the history of art and culture. In many countries, including the United States and Canada, art conservators are trained in two-to-four-year graduate programs. The training and subsequent work often requires incredible stamina, well-developed fine and gross motor skills, and the ability to see very fine detail.

We convened a roundtable to provide a platform for thoughts about disability, accessibility, and art conservation. Three art conservators, each with different personal and professional experiences with disability, gathered to discuss the thought prompts below. The discussion took place in a Google document, with no reliance on the audible voice. A condensed version is below. We explored how the art conservation profession is enriched and strengthened by accommodating practitioners with a wide variety of abilities.

(Note: There are numerous words and phrases used to refer to people who do or do not have disabilities. In this one discussion you will find more than nine. The words used are the current preferences of those using them. The preferences do not reflect the preferences of the entire disabled community.)

Fine motor skills at work as Joelle Wickens tackles the challenge of stabilizing a shattered silk flag, the United States National Flag, attributed to Clarissa Wilson, and in the care of the Betsy Ross House. (Image credit: William Donnelly)

Sarah Scaturro surface cleaning a sequined flag from the Marianne Lehmann Vodou Collection as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s Haiti Cultural Recovery Project in 2011. (Image credit: Haiti Recovery Project Team)

Please share a bit about yourself, your path in conservation, and your current role.

Wickens: I am the Associate Director of the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC) and an Assistant Professor of Preventive Conservation in the Art Conservation Department at the University of Delaware. I teach art conservation graduate students, and am responsible for guiding all aspects of the WUDPAC program. I co-lead a project called Advancing Equity and Inclusion in Conservation that’s focused on working with conservation leaders as well as early career conservators from underrepresented communities to identify and create paths to a more inclusive field. We are examining past and current projects that have tried to increase diversity in the field, determining whether these projects have achieved their intended impact, and plan to use the lessons learned to shape future efforts.

I earned a master’s degree in textile conservation from the University of Southampton in 2003, and a PhD in the conservation of 20th century foam-upholstered furniture from the same institution in 2008.

I started my training as a conservator in 2001, 2 ½ years after I was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. At that point, my disability was invisible. In the nineteen years that I have been in the field my disease has progressed, and for the last seven years, I have relied on a wheelchair to move around when I am outside of my home.

Kim: I am currently a postgraduate fellow in object conservation at Williamstown Art Conservation Center. Here, I work on a wide range of three-dimensional objects and, occasionally, do scientific analysis of materials. One of my research projects is investigating the aging properties of the materials used by a mixed media artist from the 1980s.

Prior to coming to the field of art conservation, I double-majored in physical chemistry and visual art at Brown University. I did not know about art conservation until I was nearing my senior year. So, by the time I graduated, I had not taken enough art history classes to apply to conservation programs. I briefly went to Institut Catholique de Paris to study art history, thinking I’d put my French skills into practice. Then, I enrolled in a graduate art conservation program at Queen’s University in Canada. I interned at the McCord Museum in Montreal and the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, then finished my studies in 2019. I did not expect to be back in the US so soon!

I have a severe hearing loss, so I wear a cochlear implant audio processor with hearing aid. According to my audiologist, I cannot hear well because my cochlear is “very naked without hair.” I rely heavily on lip-reading to communicate. Of course, it’s not helpful in our era of masks.

Scaturro: In April, and during the pandemic, I started a new position as the Eric and Jane Nord Chief Conservator at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Formerly, I was the Head Conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, and prior to that I was the Textile Conservator and Assistant Fashion Curator at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. I received my training from the Fashion Institute of Technology, specializing in textile and fashion conservation and curation. I’ve also just picked up my MPhil from Bard Graduate Center and am on the way towards earning my doctoral degree in design history and material culture studies. I’m writing my dissertation on the development of costume conservation in North America and Britain during the second half of the 20th century, concentrating on the shift that occurred when conservators stopped entering the field primarily through apprenticeships and instead were required to have a postgraduate degree. My studies and my amazing apprenticeship-trained mentors have taught me to be more open about who I look for when hiring a conservator. I believe that entering the field through an apprenticeship is still valid, and hopefully also has positive implications for accessibility and diversity. I personally lucked into the conservation field: I didn’t find out about it until my late twenties. When I realized there was a field that combined art, science, craft and history, my mind exploded. Luckily, I went to a public university (FIT) with less competitive admissions, that didn’t require the usual crazy hours of internships, and that happened to be one of the few schools in the world focusing on textile conservation.

Describe your understanding of and/or thoughts and feelings about the word disability and your personal experience with it.

Kim: Let’s start with a brief etymology, which is admittedly a bit contested. Currently, we use the term “disability” because “handicap” is considered politically incorrect. According to a common myth, the word “handicapped” originated in the United Kingdom under King Henry VII’s reign in the sixteenth century, when veterans became disabled and, unable to find jobs, resorted to begging on streets with “cap-in-hand”.1 In the Oxford English Dictionary, we learn the earliest use of the term was in a British betting game in 1653.2 In the nineteenth century, the term was commonly used in sports games to describe an act of making games fair by putting skilled competitors at a disadvantage, a practice that continues in golf today.

“Handicap” was used in conjunction with disability for the first time in 1915, to categorize physically disabled children, and more widely used in 1958 to describe all disabled persons, whether children or adults, and whether physically or mentally disabled, or both.3

Historically, disabled people have been seen as a liability. They were often segregated, forcibly sterilized, institutionalized, or sent to labs: not only in Nazi Germany but also in the United States and Canada. The forced sterilization of disabled people continued in the US until 1979,4 even after the 1964 Civil Rights Act: the Supreme Court ruled that forced sterilization of the disabled people did not violate the US Constitution.5 Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. even once infamously stated: “It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime… society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind… Three generations of imbeciles is enough”.6

The 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) formally granted some civil rights to the disabled in the US.7 In 1992, it was expanded to be known as “an equal opportunity law”, and recognized the need for accommodations and services in public and private sectors (e.g. transportation services). Access to electronic information technology became a law in 2010 with the Communications and Video Accessibility Act (CVAA), the year I entered my college!8

Scaturro: I didn’t realize that there was a law for electronic information technology! That shows just how ignorant we are (I am).

Kim: When I started college, the director of student accessibility services introduced me to CVAA, and told me what my rights on campus were. I looked at her really amazed and confused, as in, wait, does the Communications Access Realtime Translation (CART) service you are talking about really exist?

When I look at the history of disability in the US and Canada, I am both horrified and relieved. I feel privileged to have been given many opportunities in higher education and the workplace. Unfortunately, even though there are laws protecting our civil rights, many people are not aware of their existence, and we have to constantly advocate for the basic access we are supposed to be guaranteed. Our dignity and rights as human beings have come a long way and there is still a long road ahead.

Wickens: Sally, thank you for sharing all of this history. I knew bits and pieces of it but having this fuller story is empowering. For me, I have never felt comfortable with the word “disability,” and I have some of the same feelings about “differently-abled.” I find that both words seem to indicate that there is something else that is better. To me, we are all differently abled. We are taller, shorter, with louder and softer voices, with precise or imprecise fine motor skills, with the ability to jump high or not jump at all. Some can see far or close; some are colorblind.

Scaturro: Yes, thank you, Sally. For me, I have some hearing loss that has been partially corrected through surgery. I rely on lip-reading to clarify my understanding of what I’m hearing, which I only found out in my twenties! I don’t feel comfortable calling myself disabled, which speaks to how charged the term is, as some people use the word “disability” to reclaim it, whereas other avoid it. I don’t really tell people about my hearing loss. It’s not visible, and doesn’t really seem to impact me, so why bring it up? I prefer the term differently abled.

Kim: I grew up with hearing loss and never went to Deaf communities or schools for the deaf, so I have always been aware of how different I was from my classmates.9 I was so constantly frustrated that I decided that if I were to continue my studies in higher-education, I would go to schools where accessibility services are provided.

How has disability had an impact on your conservation career?

Kim: The main upside to being hard-of-hearing is that I am good at immersing myself in treatments. No sound will bother me. That is why I tend to be quicker than expected when doing delicate treatments: for example, stabilizing all wefts in a three-dimensional textile object, or carving a large epoxy fill to imitate the scrollwork on a Rocaille frame. Once, I was so focused on applying a lacquer coating on a bronze sculpture that I did not notice a ringing fire alarm until I was done and saw people running in the hallway! Thankfully, my colleagues noticed the issue and immediately installed visual fire alarms in different areas of the building.

There are some downsides. There are many webinars, lectures, or workshops that I wish to attend, but it is not easy to understand the context or participate in discussions if closed captioning is not provided. Job hunting is also a challenge. Many interviewers have been understanding of my situation, and either met me in-person or talked via video calls so that I could read their lips, but it is frustrating when only phone calls are accepted. Lastly, masks being worn during the pandemic have made it challenging for me to communicate at work. My colleagues have been very understanding, which I appreciate.

Wickens: My disability has had a significant impact on my conservation career. It is actually the progression of my disability from invisible to visible, and the subsequent impact on my fine motor skills as well as my ability to move large objects and climb stairs, that encouraged me to move away from textile conservation and into preventive conservation. I loved textile conservation. I loved what could be hours on end of stitching tiny stitches with invisible thread. Now I have found that I love preventive conservation even more. Caring for things before they fall apart seems so much more sustainable to me, and there is so much preventive conservation that everyone can do. I feel preventive conservation helps me empower others to care for their own cultural heritage, and it allows me to practice my craft with the current abilities of my body.

There is very little preventive conservation that I do that involves sitting or standing in front of an object working on it, a part of the job conservators call working at “the bench.” The American Institute for Conservation (AIC) defines conservation as “all those actions taken toward the long-term preservation of cultural heritage.”10 There are so many things that we do to conserve objects that don’t take place at the bench: these tasks are possibly more accessible for those with a variety of physical limitations.

Scaturro: Yes, I don’t think it’s just bench work that makes the conservator. As I’ve progressed in my career and gotten further and further away from the bench, I’ve become very self-conscious about not actually having a bench practice anymore. I do feel that some in our field are judgmental about this.

Kim: When I first started my graduate program in art conservation, I thought the job only involved benchwork. However, as you’ve pointed out, we are involved in many aspects of collections care. One of my responsibilities is emergency preparedness and response planning. I was surprised by how many emergency plans lack back-up plans in case we have at least one disabled colleague.

What can the conservation community do to become more inclusive of the disabled community?

Scaturro: As someone who hires and manages people, it’s my responsibility to be open and welcoming, and to care for my team. I believe in finding ways to craft roles that work for everyone on my team. All of my employees are different and require a unique and considered approach.

Kim: I have a question about hiring and managing people. Are people often forthcoming with what they need in order to be able to contribute well to your team? According to the ADA, employers are “prohibited from asking questions that are likely to reveal the existence of a disability before making a job offer.”11

Scaturro: Some people have been forthcoming. It certainly matters if their disability is visible or not. One person I hired was extremely forthcoming about their disability, and it was visible. I took that into consideration when setting the parameters of their tasks, but never asked them explicitly about it unless it seemed appropriate. I figured they had handled their disability all their life, could do the job at hand, and knew when they needed something. I also have had a team member who I believe has pretty significant hearing loss, but they never once mentioned it to me, and I noticed in part because I’m hypersensitive to my own hearing issues. I never brought it up, but I made sure I modulated my speech and selected the environment so that they caught everything.

Wickens: There are so many things we can do to be more inclusive, and we are considering this at the University of Delaware right now. So many of our conservation labs are inaccessible to me because I use a wheelchair. Also, we run many public tours through the labs. If others with limited mobility see that they can’t even access the labs on those tours, how are we going to convince them that conservation is a career for them?

Scaturro: I agree, Joelle. A former intern of mine who is paralyzed on one side is still considering whether or not to enter the field. They fear they won’t be welcomed or even considered. What am I to say? I hired this person, and I believe they can develop the skills to flourish in the field. I also want to believe in the good will of our colleagues. But how do we become more welcoming as a profession?

Wickens: I think we need to find a way for people to be open about many levels of disability/ability. Not being able to use your arm should not limit you from being part of caring for cultural heritage. If we wanted to bring your previous intern through our current training programs, we’d have a lot of work to do to accommodate them. However, we are beginning to think about different training pathways. Maybe there are different methods of training, combined with a broader definition of what conservation is, that can help those with a range of abilities get into conservation.

Another thing we need to consider—in conservation graduate school and beyond—is the number of hours we expect people to work. We should all be taking care of our mental and physical health while we study and/or work. If the expectation in the field is that you will give inordinate amounts of time to work, leaving little or no time to care for yourself, conservation will not be welcoming to those with mental and physical health issues. I think this is something many US professions need to consider, not just conservation. The expectation of long, long hours makes certain careers inaccessible, and usually the long hours are not actually necessary.

How are the barriers to inclusion in conservation for disabled people similar or different to those of other underrepresented groups in conservation?

Wickens: Right now white, non-disabled, middle to upper class people with a graduate level degree dominate the field. If you are outside this dominant group, there are many factors at work in keeping you out. If you are a member of more than one underrepresented group then the factors just multiply.

My description of the dominant group is based on the demographics in AICs 2014 salary survey12, and my personal experience at national and international conferences, and as a graduate school admissions committee member. It may not be 100% correct, but it is close. For our chat, can we agree it is sufficient?

Scaturro: I agree. The field is also largely women.

Wickens: So then some of the underrepresented groups in conservation are the disabled, anyone who identifies with a non-white race, LGBTQ+, lower income, and probably immigrants, first generation college graduates, and people who practice religions other than Christianity.

If we consider these groups from a different angle, we can think about visible and invisible identities. Some visible identities are race, some disabilities, and religious practice that requires specific dress. Some invisible identities may be income level, LGBTQ+ status, and family education history. Again, these comparisons are not exhaustive but they provide a lens through which we can examine barriers.

Kim: One interesting thing I heard from my colleagues is that they said, “We have not seen an art conservator who is PWD (Persons with Disabilities) as a face on AIC.” I think media representation is important. But, not all PWD are visibly disabled.

Wickens: And some may wish to hide their disabilities in images.

I used to like it when my wheelchair was not visible in an image. I didn’t want to be defined by my wheelchair and I felt like it was the only thing people saw in an image. But I’m realizing having my wheelchair visible may be an important factor in advocating for PWD, and that lack of visible representation is definitely a barrier to making a field welcoming to all.

Joelle Wickens teaching Karissa Murtore about light degradation and color-matching in textile conservation. The image was taken to be intentional about including her wheelchair. (Image credit: Melissa King)

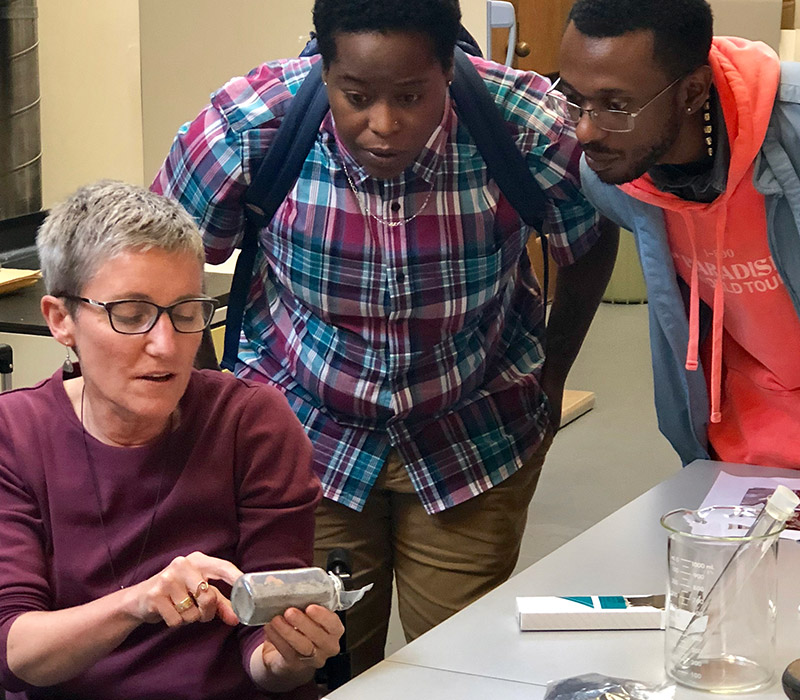

Joelle Wickens teaching Chanise Epps and ArJae Thompson about protecting objects from insect damage. She is sitting in her wheelchair but it has been cropped from the image, something she used to do with great regularity. (Image credit: Debra Hess Norris)

I see this desire to hide identities as a barrier, one that requires courage on the part of the underrepresented to reduce. When those with invisible identities are more open, it helps people realize that there are others in their identity group in conservation, even if the number is very low. I think that conservators in the dominant group are best situated to begin to break this barrier. That’s why I originally asked you, Sarah, to participate in this roundtable: because I knew you had hired an intern with partial paralysis. I did not know about your hearing loss. To now know there is a director of conservation with an invisible disability may give others the courage to share their hidden disabilities. Thank you!

Scaturro: Thank you, Joelle! I’ve gotten along well without having to actually tell anyone, but I DO have hearing loss, and it’s quite well-hidden! I think my experience has been so much easier because I’m a White woman and have the markers of the dominant group. One other non-dominant characteristic is that I come from an economic background that was not always stable and middle-class. Of course, today I’m solidly middle-class, but there were points in my childhood where my family would shop at church food pantries and day-old bread shops, and I was on the free/reduced-lunch program. I never even dreamed that a job in museums would await me, nevertheless that I would potentially need internships to get into conservation! I could never have worked for free to acquire all of the hours an applicant requires today.

Wickens: Stereotypes and implicit bias are definitely primary barriers to inclusion. For instance, people with physical disabilities are often treated as if we are less intelligent. This prejudice is just wrong, and it’s an additional barrier to being welcomed in a field that requires advanced degrees.

Kim: In 2014, among people aged 25 and older, 16.4% of PWD had completed at least a bachelor’s degree, whereas 34.6% of people who identified as having no disability had completed the same level of education. From those same groups, only 26.1% of PWD were employed and 75.9% of those “with no disability” were employed.13

Prejudices are one key barrier PWDs face. Another is that some employers believe that it will be expensive to hire people with disabilities, because of necessary investments needed for them to, as Livermore et al put it, “to achieve the same level of productivity as people without disabilities.”14 But in actuality, accommodations are seldom costly, and are worth the investment, as shown by a series of surveys done from 1992 to 1998 by the Job Accommodation Network for the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities. They found minimal productivity difference between PWDs and non-PWDs, and that 20% of accommodations were made at no cost, 80% cost $1,000 or less, 17% cost between $1,001 and $5,000, and 3% cost more than $5,000.15

Wickens: I have had an employer tell me that I should be happy to be employed by them, even though I was being paid much less than colleagues with less experience and less education. They justified my low pay because my healthcare was much more expensive. This justification is illegal, but it is difficult to fight for equal treatment.

It’s also difficult to enter such a small field, where so much entry into and progression through the field depends on who you know. If people in the field are not intentionally diversifying their circles then we will continue to promote only those who are like those already in the field.

Kim: There are no statistics about PWD in the field of art conservation, so it’s very hard to convince people in power to make change. This is why it is important to do a survey to gather data, and to address the accessibility needs of current and future conservators, something the Equity and Inclusion Committee of AIC is currently working on. The results should help us determine how to better recruit and retain people with disabilities. But to make it happen and be meaningful, we have to persuade people to take the survey.

Scaturro: I’ll admit that it was watching my little brother become paralyzed that taught me to reflect on my own biases and fear, and to intentionally welcome those who are differently-abled. I’m not sure I would have the same openness had I not experienced it first-hand with someone I love.

Wickens: That speaks to something we hear over and over again. The best way to get rid of a bias or prejudice is to really get to know someone from the group you are biased against.

Scaturro: I totally agree.

1 David Mikkelson, “Etymology of Handicap: Did the Word ‘Handicap’ Originate with the Disabled’s Having to Beg for a Living?,” in Snopes, June 16, 2011, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/handicaprice/.

2 Compact Oxford English Dictionary. (Oxford: Clarendon Press Press, 1993), s.v. “Handicap.”

3 Edwin Black, War against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race (Washington, DC: Dialog Press, 2012).

4 David Pfeiffer, “Eugenics and Disability Discrimination,” in Disability & Society 9, no. 4 (1994): pp. 481-499.

5 US Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, “Introduction to the ADA,” in Information and Technical Assistance on the Americans with Disabilities Act, n.d., https://www.ada.gov/ada_intro.htm.

6 Edwin Black, “The Horrifying American Roots of Nazi Eugenics,” in Columbian College of Arts & Sciences: History News Network, September 2003, sec. History.

7 ADA National Network, “An Overview of the Americans with Disabilities Act,” in Information, Guidance, and Training on the Americans with Disabilities Act, n.d., https://adata.org/factsheet/ADA-overview.

8 Ibid.

9 The word, Deaf, with an uppercase “D” is used to describe a person who identifies as being culturally Deaf, uses sign languages and actively engages with the Deaf communities. Deaf with a lowercase “d” is for someone who has hearing loss and does not use sign languages to communicate.

10 American Institute for Conservation, “What is Conservation?” n.d. https://www.culturalheritage.org/about-conservation/what-is-conservation.

11 US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “Job Applicants and the ADA,” in Rehabilitation Act, 29 CRF Part 1630, October 2003, https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/job-applicants-and-ada#:~:text=The%20ADA%20prohibits%20employers%20from,as%20well%20as%20medical%20examinations.

12 The Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. 2014 AIC/FA

IC Conservation Compensation Research Overview Report. Foundation of the American Institute for the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Washington, DC. 2015.

13 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. “Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics Summary 2019,” in Economics News Release, February 26, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.nr0.htm. U.S. Department of Labor. “People with a disability less likely to have completed a bachelor’s degree,” in The Economics Daily, July 20, 2015.

14 Livermore, G.A., Stapleton, D.C, Nowak, M.W., Wittenburg, D.C., and Eiseman, E.D., “The Economics of Policies and Programs Affecting the Employment of People with Disabilities,” in Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Economic Research on Employment Policy for Persons with Disabilities, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. 2000.

15 Ibid.

Main image

Sarah Scaturro cleaning a necklace by Simon Costin, “Memento Mori,” 1986

in the collection of the Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Alfred Z. Solomon-Janet A. Sloane Endowment Fund, 2006.354a–c.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

(Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Image description: A photograph of art conservator Sarah Scaturro cleaning a necklace by Simon Costin called “Memento Mori,” from 1986. Sarah is a light-skinned woman with dark brown hair pulled back in a bun; she wears a white lab coat, blue gloves, and a mask. In her left hand, she holds a cotton swab which she uses to clean the textured necklace that she holds still with her right hand.